The Cayuga Chief Jacob E. Thomas: Walking a N~Rrow Path Between Two Worlds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Decolonizing the Colonial Mind: a Personal Journey of Intercultural

Decolonizing the Colonial Mind: A Personal Journey of Intercultural Understanding, Empathy, and Mutual Respect by Gregory W.A. Saar A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department of Religion & Culture University of Manitoba Winnipeg Copyright © 2020 by Gregory W.A. Saar Saar 1 Dedication To my wife, Joyce, whose confidence in me, encouragement, and support, have always been important in everything I choose to do. To my Granddaughter, Rebekah, who, while in her first year at the University of Manitoba, uttered the words: “Grandpa, why don’t you take a class too?” To my other grandchildren Kaleb, Quintin, Alexis, and Clark, for the many ways in which they enhance my life. I hope I can play some small part in ensuring the five of you have the bright and fulfilling future you all deserve. I am confident that each one of you is capable of realising your dreams. In Memory of our daughter, Heather, who met the difficulties she faced with fortitude, courage, and determination, all the while retaining her sense of humour; an inspiration to all who were privileged to know her. Saar 2 Acknowledgements I want to express my appreciation to those without whose mentorship and assistance this theses would still be confined to the recesses of my mind. I begin with my appreciation of Dr. Renate Eigenbrod, (1944-2014) who, as Department Head of Native Studies at the University of Manitoba, took the time to interview me. -

Ritual and Religion in the Making of Humanity Roy A

Cambridge University Press 0521228735 - Ritual and Religion in the Making of Humanity Roy A. Rappaport Index More information INDEX aborigines, Australian 29, 148, 199, 202, adornment in Maring ritual 80±1 206, 213±15, 460±1 Aeschylus 41 Abrahams, I. 190, 412 air as substance 163 Abrahams, R. 33, 34, 39, 47, 381 Akkad temples 37 Absolutizing the Relative MTillich) 443 alethia Mtruth) of Logos 349 acceptance 119±23, 134, 137, 201, 224 alienation 319, 448 audience 136 Altamira caves 258 and belief 395±6 alteration in consciousness 219, 220±2, 229, common acceptance of Ultimate Sacred 257, 258 Postulates 327±8, 339 alternatives, in language 17±22, 165, 321±2, coordination of individual acts of 226±7 415, 417 disparity between inward state and 121 Altman, S. 13 and the ground of sanctity 283±7 ambiguity 88±9, 91, 95, 102±3, 151, 279 and heuristic rules 291 amelioration of falsehood 15±17 intensi®cations of 339 Americans, liturgical basis of 284±5 Native 33±4, 92, 210±12, 298±9, 380 accuracy of sentences 280 see also names of groups Achehnese people 180 analogic processes, digital representation of acquaintance-knowledge 375 86±9 activities, temporal organization of 193±6, analysis versus performance 253±7 218 Ancient Tahitian Society MOliver) 433±4 actors versus celebrants 135±6 Andaman Islanders, The MRadcliffe-Brown) acts, 220, 226 and agents 145±7 animals, in ritual 241, 242, 249, 259±60 compared in drama and ritual 136 anticipation 174 and objects 147 Antigone MSophocles) 42, 44 adaptation 5±7, 7, 9, 408±10 apostasy 133, 327 adaptive systems, hierarchy of 7, 267±8 Apostolic Constitutions Mfourth century) 191, aspects of understandings 267±8 335 as maintenance of truth 410±11 Aranda people 148 maladaptation 441±3 architecture and ritual 258 religious conceptions in human 406±8, Arioi society of Society Islands 33±4 414±19 Aristotle 41, 177, 293 structural requirements of adaptiveness art and grace 384±8 422±5 articulation of unlike systems and ritual structure of adaptive processes 419±22 occurrence 97±101 truth and falsity 443±4 Ascher, R. -

Syncretism, Revitalization and Conversion

RELIGIOUS SYNTHESIS AND CHANGE IN THE NEW WORLD: SYNCRETISM, REVITALIZATION AND CONVERSION by Stephen L. Selka, Jr. A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Schmidt College of Arts and Humanities in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, Florida August 1997 ABSTRACT Author: Stephen L. Selka. Jr. Title: Religious Synthesis and Change in the New World: Syncretism, Revitalization and Conversion Institution: Florida Atlantic University Thesis Advisor: Dr. Gerald Weiss, Ph.D. Degree: Master of Arts Year: 1997 Cases of syncretism from the New World and other areas, with a concentration on Latin America and the Caribbean, are reviewed in order to investigate the hypothesis that structural and symbolic homologies between interacting religions are preconditions for religious syncretism. In addition, definitions and models of, as well as frameworks for, syncretism are discussed in light of the ethnographic evidence. Syncretism is also discussed with respect to both revitalization movements and the recent rise of conversion to Protestantism in Latin America and the Caribbean. The discussion of syncretism and other kinds of religious change is related to va~ious theoretical perspectives, particularly those concerning the relationship of cosmologies to the existential conditions of social life and the connection between religion and world view, attitudes, and norms. 11 RELIGIOUS SYNTHESIS AND CHANGE lN THE NEW WORLD: SYNCRETISM. REVITALIZATION AND CONVERSION by Stephen L. Selka. Jr. This thesis was prepared under the direction of the candidate's thesis advisor. Dr. Gerald Weiss. Department of Anthropology, and has been approved by the members of his supervisory committee. -

[.35 **Natural Language Processing Class Here Computational Linguistics See Manual at 006.35 Vs

006 006 006 DeweyiDecimaliClassification006 006 [.35 **Natural language processing Class here computational linguistics See Manual at 006.35 vs. 410.285 *Use notation 019 from Table 1 as modified at 004.019 400 DeweyiDecimaliClassification 400 400 DeweyiDecimali400Classification Language 400 [400 [400 *‡Language Class here interdisciplinary works on language and literature For literature, see 800; for rhetoric, see 808. For the language of a specific discipline or subject, see the discipline or subject, plus notation 014 from Table 1, e.g., language of science 501.4 (Option A: To give local emphasis or a shorter number to a specific language, class in 410, where full instructions appear (Option B: To give local emphasis or a shorter number to a specific language, place before 420 through use of a letter or other symbol. Full instructions appear under 420–490) 400 DeweyiDecimali400Classification Language 400 SUMMARY [401–409 Standard subdivisions and bilingualism [410 Linguistics [420 English and Old English (Anglo-Saxon) [430 German and related languages [440 French and related Romance languages [450 Italian, Dalmatian, Romanian, Rhaetian, Sardinian, Corsican [460 Spanish, Portuguese, Galician [470 Latin and related Italic languages [480 Classical Greek and related Hellenic languages [490 Other languages 401 DeweyiDecimali401Classification Language 401 [401 *‡Philosophy and theory See Manual at 401 vs. 121.68, 149.94, 410.1 401 DeweyiDecimali401Classification Language 401 [.3 *‡International languages Class here universal languages; general -

Generative Syntax: a Cross-Linguistic Approach

Generative Syntax: A Cross-Linguistic Approach Michael Barrie Sogang University May 30, 2021 2 Generative Syntax: A Cross-Linguistic Introduction ľ 2021 by Michael Barrie is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- ShareAlike 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ (한국어: https: //creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/deed.ko) by-nc-sa/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. This license requires that reusers give credit to the creator. It allows reusers to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon the material in any medium or format, for noncommercial purposes only. If others modify or adapt the material, they must license the modified material under identical terms. Contents 1 Foundations of the Study of Language 13 1.1 The Science of Language .................................... 13 1.2 Prescriptivism versus Descriptivism .............................. 15 1.3 Evidence of Syntactic Knowledge ............................... 17 1.4 Syntactic Theorizing ....................................... 18 Key Concepts .............................................. 20 Exercises ................................................. 21 Further Reading ............................................ 22 2 The Lexicon and Theta Relations 23 2.1 Restrictions on lexical items: What words want and need ................ 23 2.2 Thematic Relations and θ-Roles ................................ 25 2.3 Lexical Entries ......................................... -

Indigenous Language Revitalization on Social Media During the Early COVID-19 Pandemic

Vol. 15 (2021), pp. 239–266 http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc http://hdl.handle.net/10125/24976 Revised Version Received: 10 Mar 2021 #KeepOurLanguagesStrong: Indigenous Language Revitalization on Social Media during the Early COVID-19 Pandemic Kari A. B. Chew University of Oklahoma Indigenous communities, organizations, and individuals work tirelessly to #Keep- OurLanguagesStrong. The COVID-19 pandemic was potentially detrimental to Indigenous language revitalization (ILR) as this mostly in-person work shifted online. This article shares findings from an analysis of public social media posts, dated March through July 2020 and primarily from Canada and the US, about ILR and the COVID-19 pandemic. The research team, affiliated with the NEȾOL- ṈEW̱ “one mind, one people” Indigenous language research partnership at the University of Victoria, identified six key themes of social media posts concerning ILR and the pandemic, including: 1. language promotion, 2. using Indigenous languages to talk about COVID-19, 3. trainings to support ILR, 4. language ed- ucation, 5. creating and sharing language resources, and 6. information about ILR and COVID-19. Enacting the principle of reciprocity in Indigenous research, part of the research process was to create a short video to share research findings back to social media. This article presents a selection of slides from the video accompanied by an in-depth analysis of the themes. Written about the pandemic, during the pandemic, this article seeks to offer some insights and understandings of a time during which much is uncertain. Therefore, this article does not have a formal conclusion; rather, it closes with ideas about long-term implications and future research directions that can benefit ILR. -

Indians in the Kanawha-New River Valley, 1500-1755 Isaac J

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2015 Maopewa iati bi: Takai Tonqyayun Monyton "To abandon so beautiful a Dwelling": Indians in the Kanawha-New River Valley, 1500-1755 Isaac J. Emrick Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Emrick, Isaac J., "Maopewa iati bi: Takai Tonqyayun Monyton "To abandon so beautiful a Dwelling": Indians in the Kanawha-New River Valley, 1500-1755" (2015). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 5543. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/5543 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Research Repository @ WVU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maopewa iati bi: Takai Toñqyayuñ Monyton “To abandon so beautiful a Dwelling”: Indians in the Kanawha-New River Valley, 1500-1755 Isaac J. Emrick Dissertation submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Tyler Boulware, Ph.D., Chair Kenneth Fones-Wolf, Ph.D. Joseph Hodge, Ph.D. Michele Stephens, Ph.D. Department of History & Amy Hirshman, Ph.D. Department of Sociology and Anthropology Morgantown, West Virginia 2015 Keywords: Native Americans, Indian History, West Virginia History, Colonial North America, Diaspora, Environmental History, Archaeology Copyright 2015 Isaac J. Emrick ABSTRACT Maopewa iati bi: Takai Toñqyayuñ Monyton “To abandon so beautiful a Dwelling”: Indians in the Kanawha-New River Valley, 1500-1755 Isaac J. -

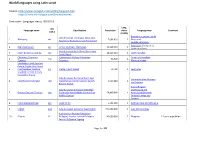

World Languages Using Latin Script

World languages using Latin script Source: http://www.omniglot.com/writing/langalph.htm https://www.ethnologue.com/browse/names Sort order : Language status, ISO 639-3 Lang, ISO Language name Classification Population status Language map Comment 639-3 (EGIDS) Botswana, Lesotho, South Indo-European, Germanic, West, Low 1. Afrikaans, afr 7,096,810 1 Africa and Saxon-Low Franconian, Low Franconian SwazilandNamibia Azerbaijan,Georgia,Iraq 2. Azeri,Azerbaijani azj Turkic, Southern, Azerbaijani 24,226,940 1 Jordan and Syria Indo-European Balto-Slavic Slavic West 3. Czech Bohemian Cestina ces 10,619,340 1 Czech Republic Czech-Slovak Chamorro,Chamorru Austronesian Malayo-Polynesian Guam and Northern 4. cha 94,700 1 Tjamoro Chamorro Mariana Islands Seychelles Creole,Seselwa Creole, Creole, Ilois, Kreol, 5. Kreol Seselwa, Seselwa, crs Creole, French based 72,700 1 Seychelles Seychelles Creole French, Seychellois Creole Indo-European Germanic North East Denmark Finland Norway 6. DanishDansk Rigsdansk dan Scandinavian Danish-Swedish Danish- 5,520,860 1 and Sweden Riksmal Danish AustriaBelgium Indo-European Germanic West High Luxembourg and 7. German Deutsch Tedesco deu German German Middle German East 69,800,000 1 NetherlandsDenmark Middle German Finland Norway and Sweden 8. Estonianestieesti keel ekk Uralic Finnic 1,132,500 1 Estonia Latvia and Lithuania 9. English eng Indo-European Germanic West English 341,000,000 1 over 140 countries Austronesian Malayo-Polynesian 10. Filipino fil Philippine Greater Central Philippine 45,000,000 1 Filippines L2 users population Central Philippine Tagalog Page 1 of 48 World languages using Latin script Lang, ISO Language name Classification Population status Language map Comment 639-3 (EGIDS) Denmark Finland Norway 11. -

Magic and Ritual in the Ancient World

MAGIC AND RITUAL IN THE ANCIENT WORLD PAUL MIRECKI MARVIN MEYER, Editors BRILL RGRW.Mirecki/Meyer.141.vwc 19-11-2001 14:34 Pagina I MAGIC AND RITUAL IN THE ANCIENT WORLD RGRW.Mirecki/Meyer.141.vwc 19-11-2001 14:34 Pagina II RELIGIONS IN THE GRAECO-ROMAN WORLD EDITORS R. VAN DEN BROEK H. J.W. DRIJVERS H.S. VERSNEL VOLUME 141 RGRW.Mirecki/Meyer.141.vwc 19-11-2001 14:34 Pagina III MAGIC AND RITUAL IN THE ANCIENT WORLD EDITED BY PAUL MIRECKI AND MARVIN MEYER BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON • KÖLN 2002 RGRWMIRE.VWC 6/2/2004 9:18 AM Page iv This series Religions in the Graeco-Roman World presents a forum for studies in the social and cultural function of religions in the Greek and the Roman world, dealing with pagan religions both in their own right and in their interaction with and influence on Christianity and Judaism during a lengthy period of fundamental change. Special attention will be given to the religious history of regions and cities which illustrate the practical workings of these processes. Enquiries regarding the submission of works for publication in the series may be directed to Professor H.J.W. Drijvers, Faculty of Letters, University of Groningen, 9712 EK Groningen, The Netherlands. This book is printed on acid-free paper. Die Deutsche Bibliothek – CIP-Einheitsaufnahme Magic and ritual in the ancient world / ed. by Paul Mirecki and Marvin Meyer. – Leiden ; Boston ; Köln : Brill, 2001 (Religions in the Graeco-Roman world ; Vol. 141) ISBN 90–04–10406–2 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Library of Congress Cataloging-in Publication Data is also available ISSN 0927-7633 ISBN 90 04 11676 1 © Copyright 2002 by Koninklijke Brill nv, Leiden, The Netherlands All rights reserved. -

The American Indians Respond to European Contact

Native movements: the American Indians respond to European contact Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Rich, Stephen Thomas, 1945- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 27/09/2021 02:56:38 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/552044 NATIVE MOVEMENTS: THE AMERICAN INDIANS RESPOND TO EUROPEAN CONTACT by Stephen Thomas Rich A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1 9 6 9 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholarship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. SIGNED: £ < A APPROVAL BY THESIS DIRECTOR This thesis has been approved on the date shown below: /z, /f£f Edward P. -

J.N.B. Hewitt Photographs of Iroquois People on the Six Nations Reservation, Circa 1897-Circa 1937

J.N.B. Hewitt photographs of Iroquois people on the Six Nations Reservation, circa 1897-circa 1937 Gina Rappaport and Eden Orelove April 2016 National Anthropological Archives Museum Support Center 4210 Silver Hill Road Suitland, Maryland 20746 [email protected] http://www.anthropology.si.edu/naa/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical note............................................................................................................. 2 Arrangement note............................................................................................................ 3 Scope and Contents note................................................................................................ 3 Publication Note............................................................................................................... 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 J.N.B. Hewitt photographs of Iroquois people on the Six Nations Reservation, circa 1897-circa 1937 NAA.PhotoLot.155 Collection Overview Repository: National Anthropological Archives Title: J.N.B. Hewitt photographs of Iroquois people on -

3115 Eblj Article 2 (Was 3), 2008:Eblj Article

Early Northern Iroquoian Language Books in the British Library Adrian S. Edwards An earlier eBLJ article1 surveyed the British Library’s holdings of early books in indigenous North American languages through the example of Eastern Algonquian materials. This article considers antiquarian materials in or about Northern Iroquoian, a different group of languages from the eastern side of the United States and Canada. The aim as before is to survey what can be found in the Library, and to place these items in a linguistic and historical context. In scope are printed media produced before the twentieth century, in effect from 1545 to 1900. ‘I’ reference numbers in square brackets, e.g. [I1], relate to entries in the Chronological Checklist given as an appendix. The Iroquoian languages are significant for Europeans because they were the first indigenous languages to be recorded in any detail by travellers to North America. The family has traditionally been divided into a northern and southern branch by linguists. So far only Cherokee has been confidently allocated to the southern branch, although it is possible that further languages became extinct before their existence was recorded by European visitors. Cherokee has always had a healthy literature and merits an article of its own. This survey therefore will look only at the northern branch. When historical records began in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the Northern Iroquoian languages were spoken in a large territory centred on what is now the north half of the State of New York, extending across the St Lawrence River into Quebec and Ontario, and southwards into Pennsylvania.