Indigenous Language Revitalization on Social Media During the Early COVID-19 Pandemic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Considerations for Non-Dominant Language Education in the Global South

FIRE: Forum for International Research in Education Vol. 5, Iss. 3, 2019, pp. 12-28 LANGUAGE-IN-EDUCATION POLICIES AND INDIGENOUS LANGUAGE REVITALIZATION EFFORTS IN CANADA: CONSIDERATIONS FOR NON-DOMINANT LANGUAGE EDUCATION IN THE GLOBAL SOUTH Onowa McIvor1 University of Victoria, Canada Jessica Ball University of Victoria, Canada Abstract Indigenous languages are struggling for breath in the Global North. In Canada, Indigenous language medium schools and early childhood programs remain independent and marginalized. Despite government commitments, there is little support for Indigenous language-in-education policy and initiatives. This article describes an inaugural, country- wide, federally-funded, Indigenous-led language revitalization research project, entitled NE OL EW̱ (one mind-one people). The project brings together nine Indigenous partners to build a country-wide network and momentum to pressure multi-levels of government to honourȾ agreementsṈ enshrining the right of children to learn their Indigenous language. The project is documenting approaches to create new Indigenous language speakers, focusing on adult language learners able to keep the language vibrant and teach their language to children. The article reflects upon how this Northern emphasis on Indigenous language revitalization and country-wide networking initiative is relevant to mother tongue-based education and policy examples in the Global South. The article underscores the need for both community level initiatives (top-down) and government level policy and funding (bottom up) to support child and adult Indigenous language learning. Keywords: Indigenous language practices, language-in-education policies, policy reform, First Nations, Indigenous, Canada, Global North, Global South 1 Correspondence: Dr. Onowa McIvor, C/O Dept. of Indigenous Education, University of Victoria, PO Box 1700 STN CSC, Victoria BC V8W 2Y2; Email: [email protected] O. -

Youth, Technology and Indigenous Language Revitalization in Indonesia

Youth, Technology and Indigenous Language Revitalization in Indonesia Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Putra, Kristian Adi Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction, presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 24/09/2021 19:51:25 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/630210 YOUTH, TECHNOLOGY AND INDIGENOUS LANGUAGE REVITALIZATION IN INDONESIA by Kristian Adi Putra ______________________________ Copyright © Kristian Adi Putra 2018 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the GRADUATE INTERDISCIPLINARY PROGRAM IN SECOND LANGUAGE ACQUISITION AND TEACHING In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2018 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Kristian Adi Putra, titled Youth, Technology and Indigenous Language Revitalization in Indonesia and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. -~- ------+-----,T,___~-- ~__ _________ Date: (4 / 30/2018) Leisy T Wyman - -~---~· ~S:;;;,#--,'-L-~~--~- -------Date: (4/30/2018) 7 Jonath:2:inhardt ---12Mij-~-'-+--~4---IF-'~~~~~"____________ Date: (4 / 30 I 2018) Perry Gilmore Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate' s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this dissertation prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement. -

[.35 **Natural Language Processing Class Here Computational Linguistics See Manual at 006.35 Vs

006 006 006 DeweyiDecimaliClassification006 006 [.35 **Natural language processing Class here computational linguistics See Manual at 006.35 vs. 410.285 *Use notation 019 from Table 1 as modified at 004.019 400 DeweyiDecimaliClassification 400 400 DeweyiDecimali400Classification Language 400 [400 [400 *‡Language Class here interdisciplinary works on language and literature For literature, see 800; for rhetoric, see 808. For the language of a specific discipline or subject, see the discipline or subject, plus notation 014 from Table 1, e.g., language of science 501.4 (Option A: To give local emphasis or a shorter number to a specific language, class in 410, where full instructions appear (Option B: To give local emphasis or a shorter number to a specific language, place before 420 through use of a letter or other symbol. Full instructions appear under 420–490) 400 DeweyiDecimali400Classification Language 400 SUMMARY [401–409 Standard subdivisions and bilingualism [410 Linguistics [420 English and Old English (Anglo-Saxon) [430 German and related languages [440 French and related Romance languages [450 Italian, Dalmatian, Romanian, Rhaetian, Sardinian, Corsican [460 Spanish, Portuguese, Galician [470 Latin and related Italic languages [480 Classical Greek and related Hellenic languages [490 Other languages 401 DeweyiDecimali401Classification Language 401 [401 *‡Philosophy and theory See Manual at 401 vs. 121.68, 149.94, 410.1 401 DeweyiDecimali401Classification Language 401 [.3 *‡International languages Class here universal languages; general -

Language Revitalization Grade 4

Language Revitalization Grade 4 HEALTH Language Revitalization Overview ESSENTIAL UNDERSTANDINGS • Language This lesson explores the preservation and revital- ization of Indigenous languages—why it’s import- LEARNING OUTCOMES ant and what tribes in Oregon are doing to keep • Students can describe language their ancestral languages alive. This is important for revitalization and identify one or many Native American tribes, who are attempting more revitalization tools or practices. to save their languages from “linguicide” caused • Students can describe why tribes by decades of colonialism and forced assimila- in Oregon want to revitalize and or tion. Language revitalization can help restore and maintain their ancestral languages. strengthen cultural connections and pride, which • Students can connect language revital- in turn can promote well-being for both tribes and ization to restoring cultural pride and the benefits of that pride for group and their members. individual well-being. Background for teachers ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS • What is language revitalization, Language is an essential part of human identity and what are some ways people and shapes how we view the world. For many revitalize languages? Native American tribes, however, language is a • Why do the nine federally recognized complicated and even painful subject. Euro-Amer- tribes in Oregon feel it is important ican government officials, teachers, and other to revitalize and/or maintain their ancestral languages? authorities discouraged Native American and Alaska Native people -

Generative Syntax: a Cross-Linguistic Approach

Generative Syntax: A Cross-Linguistic Approach Michael Barrie Sogang University May 30, 2021 2 Generative Syntax: A Cross-Linguistic Introduction ľ 2021 by Michael Barrie is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- ShareAlike 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ (한국어: https: //creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/deed.ko) by-nc-sa/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. This license requires that reusers give credit to the creator. It allows reusers to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon the material in any medium or format, for noncommercial purposes only. If others modify or adapt the material, they must license the modified material under identical terms. Contents 1 Foundations of the Study of Language 13 1.1 The Science of Language .................................... 13 1.2 Prescriptivism versus Descriptivism .............................. 15 1.3 Evidence of Syntactic Knowledge ............................... 17 1.4 Syntactic Theorizing ....................................... 18 Key Concepts .............................................. 20 Exercises ................................................. 21 Further Reading ............................................ 22 2 The Lexicon and Theta Relations 23 2.1 Restrictions on lexical items: What words want and need ................ 23 2.2 Thematic Relations and θ-Roles ................................ 25 2.3 Lexical Entries ......................................... -

Europe's Regional Languages in Perspective Michael Hornsby And

Journal on Ethnopolitics and Minority Issues in Europe Vol 11, No 1, 2012, 88-116 Copyright © ECMI 24 April 2012 This article is located at: http://www.ecmi.de/fileadmin/downloads/publications/JEMIE/2012/HornsbyAgarin.pdf The End of Minority Languages? Europe’s Regional Languages in Perspective Michael Hornsby and Timofey Agarin* John Paul II Catholic University, Lublin and Queen’s University Belfast The European Union (EU) today counts 23 national languages with as many as 65 regional and minority languages, only a few of which enjoy recognition in the EU. We assess the perspectives of regional and, particularly, endangered languages in Europe in three steps. First, we argue that current approach of nation-states, defining both national and regional/minority languages from the top down, is increasingly at odds with the idea of cross-border migration and communications. We illustrate this with the examples of Estonian and Latvian, official languages of EU member-states with around one million native speakers each. Second, we attest the end of “traditional” forms of minority language, contending that if they are to survive they cannot do so as mirror copies of majority languages. To make our point clear, we discuss regional efforts to increase the use of the Breton and the Welsh languages. We outline a research agenda that takes into account the nation-state dominated linguistic regulations and the future of an increasingly borderless Europe, and suggest how both can be accommodated. Key words: EU; regional languages; minority languages; Welsh; Breton; Latvian; Estonian; multilingualism; language policy Today the official languages of the European Union (EU) member-states enjoy de jure equality across the union, even outside the territory of the state that recognizes them as official. -

Global Survey of Revitalization Efforts: a Mixed Methods Approach to Understanding Language Revitalization Practices

Vol. 13 (2019), pp. 446–513 http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc http://hdl.handle.net/10125/24871 Revised Version Received: 22 May 2019 Global Survey of Revitalization Efforts: A mixed methods approach to understanding language revitalization practices Gabriela Pérez Báez University of Oregon & Smithsonian Institution Rachel Vogel Cornell University Uia Patolo Auckland University of Technology The world’s linguistic diversity, estimated at over 7,000 languages, is declining rapidly. As awareness about this has increased, so have responses from a number of stakeholders. In this study we present the results of the Global Survey of Re- vitalization Efforts carried out by a mixed methods approach and comparative analysis of revitalization efforts worldwide. The Survey included 30 questions, was administered online in 7 languages, and documented 245 revitalization ef- forts yielding some 40,000 bits of data. In this study, we report on frequency counts and show, among other findings, that revitalization efforts are heavily fo- cused on language teaching, perhaps over intergenerational transmission of a lan- guage, and rely heavily on community involvement although do not only involve language community members exclusively. The data also show that support for language revitalization in the way of funding, as well as endorsement, is critical to revitalization efforts. This study also makes evident the social, cultural, polit- ical, and geographic gaps in what we know about revitalization worldwide. We hope that this study will strengthen broad interest and commitment to studying, understanding, and supporting language revitalization as an integral aspect of the history of human language in the 21st century. 1. Introduction1 The world’s linguistic diversity is estimated to encompass over 7,000 languages (Hammarström et al. -

The Cayuga Chief Jacob E. Thomas: Walking a N~Rrow Path Between Two Worlds

THE CAYUGA CHIEF JACOB E. THOMAS: WALKING A N~RROW PATH BETWEEN TWO WORLDS Takeshi Kimura Faculty of Humanities Yamaguchi University 1677-1 Yoshida Yamaguchi-shi 753-8512 Japan Abstract I Resume The Cayuga Chief Jacob E. Thomas (1922-1998) of the Six Nations Reserve, Ontario, worked on teaching and preserving the oral Native languages and traditions ofthe Longhouse by employing modern technolo gies such as audio- and video recorders and computers. His primary concern was to transmit and document them as much as possible in the face of their possible loss. Especially, he emphasized teaching the lan guage and religious knowledge together. In this article, researched and written before his death, I discuss the way he taught his classes, examine the educational materials he produced, and assess their features. I also examine several reactions toward his efforts among Native people. De son vivant Jacob E. Thomas (1922-1998), chef des Cayugas de la Reserve des Six Nations, en Ontario, a travaille a I'enseignement et a la preservation des langues parlees autochtones et des traditions du Long house. Pour ce faire, il a eu recours aux techniques d'enregistrement audio et video ainsi qu'a I'informatique. Devant Ie declin possible des langues et des traditions autochtones, son but principal a ete de les enregistrer et de les classifier pour les rendre accessible a tous. II a particulierement mis I'accent sur la necessite d'enseigner conjointement la langue et la religion. Dans cet article, dont la recherche et la redaction ont ete accomplies avant la mort de Thomas, j'examine son enseignement en ciasse de meme que Ie materiel pedagogique qu'il a cree et en evalue les caracteristiques. -

The Role of Hebrew in Jewish Language Endangerment

The Cost of Revival: the Role of Hebrew in Jewish Language Endangerment Elizabeth Freeburg Adviser: Claire Bowern Submitted to the Faculty of the Department of Linguistics in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of the Arts. Yale University May 1, 2013 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract 2 Acknowledgements 3 1. Introduction 4 2. Terminology 8 3. The Hebrew Revival 10 4. Jewish Languages in Israel 18 4.1 Karaim 4.2 Ladino 4.3 Yiddish 4.4 Lessons of the Haredim 4.5 JLOTHs in Comparison 5. Conclusions 48 5.1 Language revival and linguistics 5.2 Moving forward References 54 2 ABSTRACT In the nineteenth century, Hebrew had no native speakers; currently, it has nearly eight million. The growth of Hebrew from a “dead” language to the official language of Israel is often described as the most successful language revival project of all time. However, less well-known is the effect that the revival of Hebrew has had on other languages spoken in Israel, specifically those classified as Jewish languages. With one exception, all Jewish languages other than Hebrew have become endangered in the past century, and their speakers have in large part shifted to become Hebrew speakers. In this essay, I use morphosyntactic, lexical, and population data to examine the status of three such languages in Israel: Karaim, Ladino, and Yiddish. I also outline the methods used in the Hebrew revival and how they affected the status of other Jewish languages in Israel, including what circumstances have prevented Yiddish from becoming endangered. By using historical and linguistic evidence to draw connections between the Hebrew revival and the endangerment of other Jewish languages, my essay calls into question the usefulness of the Hebrew revival as an inspirational model for other language revival projects. -

Matukar-Panau: a Case Study in Language Revitalization*

Matukar-Panau: A case study in language revitalization* Theresa Sepulveda Senior Linguistics Thesis Swarthmore College 2010 …we must do some serious rethinking of our priorities, lest linguistics go down in history as the only science that presided obliviously over the disappearance of 90% of the very field to which it is dedicated. -Michael Krauss (1992), ―The world‘s languages in crisis‖ in Language 68 (1):10 Abstract This case study in language revitalization focuses on the Oceanic language of Matukar-Panau from Papua New Guinea. Recent work on a talking dictionary of Matukar in Swarthmore College‘s Laboratory for Endangered Languages Research and Documentation as well as the development of an orthography and first book in Matukar will be evaluated in terms of the viability of Matukar in the 21st century. I will first present the sociolinguistic background of Matukar in order to examine the extent and cause of Matukar‘s endangerment. Categories will include the history, geography, government recognition of, and demography of, Matukar and Matukar villagers (Tsunoda 2005). An emphasis will be placed on the reaction of the ethnic group of Matukar villagers to the growing dominance of Tok Pisin and the corresponding language shift (Dorian 1981). Next, I will examine the language endangerment phenomenon and define language death. In order to classify Matukar on a scale of language endangerment, I will describe Michael Krauss‘s (2007) and Joshua Fishman‘s (1991) classification systems of language vitality. I will then present Matukar‘s ratings based on UNESCO‘s document on language vitality and endangerment (2003). These systems provide a quantitative way to identify the characteristics of a dying language in areas such as age of speaker population, domains of language use, and availability of written material. -

World Languages Using Latin Script

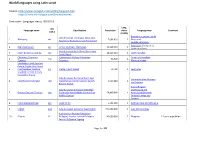

World languages using Latin script Source: http://www.omniglot.com/writing/langalph.htm https://www.ethnologue.com/browse/names Sort order : Language status, ISO 639-3 Lang, ISO Language name Classification Population status Language map Comment 639-3 (EGIDS) Botswana, Lesotho, South Indo-European, Germanic, West, Low 1. Afrikaans, afr 7,096,810 1 Africa and Saxon-Low Franconian, Low Franconian SwazilandNamibia Azerbaijan,Georgia,Iraq 2. Azeri,Azerbaijani azj Turkic, Southern, Azerbaijani 24,226,940 1 Jordan and Syria Indo-European Balto-Slavic Slavic West 3. Czech Bohemian Cestina ces 10,619,340 1 Czech Republic Czech-Slovak Chamorro,Chamorru Austronesian Malayo-Polynesian Guam and Northern 4. cha 94,700 1 Tjamoro Chamorro Mariana Islands Seychelles Creole,Seselwa Creole, Creole, Ilois, Kreol, 5. Kreol Seselwa, Seselwa, crs Creole, French based 72,700 1 Seychelles Seychelles Creole French, Seychellois Creole Indo-European Germanic North East Denmark Finland Norway 6. DanishDansk Rigsdansk dan Scandinavian Danish-Swedish Danish- 5,520,860 1 and Sweden Riksmal Danish AustriaBelgium Indo-European Germanic West High Luxembourg and 7. German Deutsch Tedesco deu German German Middle German East 69,800,000 1 NetherlandsDenmark Middle German Finland Norway and Sweden 8. Estonianestieesti keel ekk Uralic Finnic 1,132,500 1 Estonia Latvia and Lithuania 9. English eng Indo-European Germanic West English 341,000,000 1 over 140 countries Austronesian Malayo-Polynesian 10. Filipino fil Philippine Greater Central Philippine 45,000,000 1 Filippines L2 users population Central Philippine Tagalog Page 1 of 48 World languages using Latin script Lang, ISO Language name Classification Population status Language map Comment 639-3 (EGIDS) Denmark Finland Norway 11. -

3115 Eblj Article 2 (Was 3), 2008:Eblj Article

Early Northern Iroquoian Language Books in the British Library Adrian S. Edwards An earlier eBLJ article1 surveyed the British Library’s holdings of early books in indigenous North American languages through the example of Eastern Algonquian materials. This article considers antiquarian materials in or about Northern Iroquoian, a different group of languages from the eastern side of the United States and Canada. The aim as before is to survey what can be found in the Library, and to place these items in a linguistic and historical context. In scope are printed media produced before the twentieth century, in effect from 1545 to 1900. ‘I’ reference numbers in square brackets, e.g. [I1], relate to entries in the Chronological Checklist given as an appendix. The Iroquoian languages are significant for Europeans because they were the first indigenous languages to be recorded in any detail by travellers to North America. The family has traditionally been divided into a northern and southern branch by linguists. So far only Cherokee has been confidently allocated to the southern branch, although it is possible that further languages became extinct before their existence was recorded by European visitors. Cherokee has always had a healthy literature and merits an article of its own. This survey therefore will look only at the northern branch. When historical records began in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the Northern Iroquoian languages were spoken in a large territory centred on what is now the north half of the State of New York, extending across the St Lawrence River into Quebec and Ontario, and southwards into Pennsylvania.