International Law/The Great Law of Peace

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Deadlands: Reloaded Core Rulebook

This electronic book is copyright Pinnacle Entertainment Group. Redistribution by print or by file is strictly prohibited. This pdf may be printed for personal use. The Weird West Reloaded Shane Lacy Hensley and BD Flory Savage Worlds by Shane Lacy Hensley Credits & Acknowledgements Additional Material: Simon Lucas, Paul “Wiggy” Wade-Williams, Dave Blewer, Piotr Korys Editing: Simon Lucas, Dave Blewer, Piotr Korys, Jens Rushing Cover, Layout, and Graphic Design: Aaron Acevedo, Travis Anderson, Thomas Denmark Typesetting: Simon Lucas Cartography: John Worsley Special Thanks: To Clint Black, Dave Blewer, Kirsty Crabb, Rob “Tex” Elliott, Sean Fish, John Goff, John & Christy Hopler, Aaron Isaac, Jay, Amy, and Hayden Kyle, Piotr Korys, Rob Lusk, Randy Mosiondz, Cindi Rice, Dirk Ringersma, John Frank Rosenblum, Dave Ross, Jens Rushing, Zeke Sparkes, Teller, Paul “Wiggy” Wade-Williams, Frank Uchmanowicz, and all those who helped us make the original Deadlands a premiere property. Fan Dedication: To Nick Zachariasen, Eric Avedissian, Sean Fish, and all the other Deadlands fans who have kept us honest for the last 10 years. Personal Dedication: To mom, dad, Michelle, Caden, and Ronan. Thank you for all the love and support. You are my world. B.D.’s Dedication: To my parents, for everything. Sorry this took so long. Interior Artwork: Aaron Acevedo, Travis Anderson, Chris Appel, Tom Baxa, Melissa A. Benson, Theodor Black, Peter Bradley, Brom, Heather Burton, Paul Carrick, Jim Crabtree, Thomas Denmark, Cris Dornaus, Jason Engle, Edward Fetterman, -

The Cultural Paradigms of British Imperialism in the Militarisation of Scotland and North America, C.1745-1775

1 The Cultural Paradigms of British Imperialism in the Militarisation of Scotland and North America, c.1745-1775. Nicola Martin Date of Submission: 24th September 2018 This thesis is submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Arts and Humanities University of Stirling 2 3 Abstract This dissertation examines militarisation in Scotland and North America from the Jacobite Uprising of 1745-46 to the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War in 1775. Employing a biographical, case study approach, it investigates the cultural paradigms guiding the actions and understandings of British Army officers as they waged war, pacified hostile peoples, and attempted to assimilate ‘other’ population groups within the British Empire. In doing so, it demonstrates the impact of the Jacobite Uprising on British imperialism in North America and the role of militarisation in affecting the imperial attitudes of military officers during a transformative period of imperial expansion, areas underexplored in the current historiography. It argues that militarisation caused several paradigm shifts that fundamentally altered how officers viewed imperial populations and implemented empire in geographical fringes. Changes in attitude led to the development of a markedly different understanding of imperial loyalty and identity. Civilising savages became less important as officers moved away from the assimilation of ‘other’ populations towards their accommodation within the empire. Concurrently, the status of colonial settlers as Britons was contested due to their perceived disloyalty during and after the French and Indian War. ‘Othering’ colonial settlers, officers questioned the sustainability of an ‘empire of negotiation’ and began advocating for imperial reform, including closer regulation of the thirteen colonies. -

Now Have Taken up the Hatchet Against Them”: Braddock’S Defeat and the Martial Liberation of the Western Delawares

We “Now Have Taken up the Hatchet against Them”: Braddock’s Defeat and the Martial Liberation of the Western Delawares N 1755 WESTERN PENNSYLVANIA became the setting for a series of transforming events that resonated throughout the colonial world of INorth America. On July 9, on the banks of the Monongahela River— seven miles from the French stronghold of Fort Duquesne—two regi- ments of the British army, together with over five companies of colonial militia, suffered a historic mauling at the hands of a smaller force of French marines, Canadian militia, and Great Lakes Indians. With nearly one thousand casualties, the defeat of General Edward Braddock’s com- mand signified the breakdown of British presence on the northern Appalachian frontier. This rout of British-American forces also had an immense effect on the future of Indians in the Ohio Country, particularly the peoples of western Pennsylvania referred to as the Delawares. I would like to thank the anonymous readers and my teachers and trusted colleagues, Dr. Holly Mayer of Duquesne University and Dr. Mary Lou Lustig, emeritus West Virginia University, for their constructive criticisms and helpful suggestions as I worked through the revision process for this article. THE PENNSYLVANIA MAGAZINE OF HISTORY AND BIOGRAPHY Vol. CXXXVII, No. 3 ( July 2013) 228 RICHARD S. GRIMES July From late October 1755 through the spring of 1756, Delaware war parties departing from their principal western Pennsylvania town of Kittanning and from the east in the Susquehanna region converged on the American backcountry. There they inflicted tremendous loss of life and cataclysmic destruction of property on the settlements of Pennsylvania and Virginia. -

Indigenous People of Western New York

FACT SHEET / FEBRUARY 2018 Indigenous People of Western New York Kristin Szczepaniec Territorial Acknowledgement In keeping with regional protocol, I would like to start by acknowledging the traditional territory of the Haudenosaunee and by honoring the sovereignty of the Six Nations–the Mohawk, Cayuga, Onondaga, Oneida, Seneca and Tuscarora–and their land where we are situated and where the majority of this work took place. In this acknowledgement, we hope to demonstrate respect for the treaties that were made on these territories and remorse for the harms and mistakes of the far and recent past; and we pledge to work toward partnership with a spirit of reconciliation and collaboration. Introduction This fact sheet summarizes some of the available history of Indigenous people of North America date their history on the land as “since Indigenous people in what is time immemorial”; some archeologists say that a 12,000 year-old history on now known as Western New this continent is a close estimate.1 Today, the U.S. federal government York and provides information recognizes over 567 American Indian and Alaskan Native tribes and villages on the contemporary state of with 6.7 million people who identify as American Indian or Alaskan, alone Haudenosaunee communities. or combined.2 Intended to shed light on an often overlooked history, it The land that is now known as New York State has a rich history of First includes demographic, Nations people, many of whom continue to influence and play key roles in economic, and health data on shaping the region. This fact sheet offers information about Native people in Indigenous people in Western Western New York from the far and recent past through 2018. -

A White 050203.Pdf (420.1Kb)

'KEEPING CLEAR FROM THE GAIN OF OPPRESSION': 'PUBLIC FRIENDS' AND THE DE-MASTERING OF QUAKER RACE RELATIONS IN LATE COLONIAL AMERICA By ANDREW PIERCE WHITE A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY Department of English MAY 2003 ii To the Faculty of Washington State University: The members of the Committee appointed to examine the dissertation of ANDREW PIERCE WHITE find it satisfactory and recommend that it be accepted. _______________________________ Chair _______________________________ _______________________________ iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are many people to whom I owe the debt of gratitude for the completion of this dissertation, the culmination of six years of graduate school. First and foremost, I want to thank my advisor, Albert von Frank, for encouraging me to delve more deeply into Quaker life-writings. During my studies, he consistently has challenged me to explore the lesser known bi-ways of early American literature, in order that I might contribute something fresh and insightful to the field. Through his exemplary thoroughness, he has also helped me to improve the clarity of my writing. I owe much to Joan Burbick and Alexander Hammond, who both pointed to the context of British colonial discourse, in which many of the texts I consider were written. That particular advice has been invaluable in the shaping of the theoretical framework of this study. In addition, I would like to thank Nelly Zamora, along with Ann Berry and Jerrie Sinclair, for their administrative support and guidance during my studies at Washington State University. I also am grateful to the Department of English for generously providing a Summer Dissertation Fellowship in 2001, which made it possible for me to do research in the Philadelphia area. -

Indigenous Laws for Making and Maintaining Relations Against the Sovereignty of the State

We All Belong: Indigenous Laws for Making and Maintaining Relations Against the Sovereignty of the State by Amar Bhatia A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Juridical Science Faculty of Law University of Toronto © Copyright by Amar Bhatia 2018 We All Belong: Indigenous Laws for Making and Maintaining Relations Against the Sovereignty of the State Amar Bhatia Doctor of Juridical Science Faculty of Law University of Toronto 2018 Abstract This dissertation proposes re-asserting Indigenous legal authority over immigration in the face of state sovereignty and ongoing colonialism. Chapter One examines the wider complex of Indigenous laws and legal traditions and their relationship to matters of “peopling” and making and maintaining relations with the land and those living on it. Chapter Two shows how the state came to displace the wealth of Indigenous legal relations described in Chapter One. I mainly focus here on the use of the historical treaties and the Indian Act to consolidate Canadian sovereignty at the direct expense of Indigenous laws and self- determination. Conventional notions of state sovereignty inevitably interrupt the revitalization of Indigenous modes of making and maintaining relations through treaties and adoption. Chapter Three brings the initial discussion about Indigenous laws and treaties together with my examination of Canadian sovereignty and its effect on Indigenous jurisdiction over peopling. I review the case of a Treaty One First Nation’s customary adoption of a precarious status migrant and the related attempt to prevent her removal from Canada on this basis. While this attempt was ii unsuccessful, I argue that an alternative approach to treaties informed by Indigenous laws would have recognized the staying power of Indigenous adoption. -

What Was the Iroquois Confederacy?

04 AB6 Ch 4.11 4/2/08 11:22 AM Page 82 What was the 4 Iroquois Confederacy? Chapter Focus Questions •What was the social structure of Iroquois society? •What opportunities did people have to participate in decision making? •What were the ideas behind the government of the Iroquois Confederacy? The last chapter explored the government of ancient Athens. This chapter explores another government with deep roots in history: the Iroquois Confederacy. The Iroquois Confederacy formed hundreds of years ago in North America — long before Europeans first arrived here. The structure and principles of its government influenced the government that the United States eventually established. The Confederacy united five, and later six, separate nations. It had clear rules and procedures for making decisions through representatives and consensus. It reflected respect for diversity and a belief in the equality of people. Pause The image on the side of this page represents the Iroquois Confederacy and its five original member nations. It is a symbol as old as the Confederacy itself. Why do you think this symbol is still honoured in Iroquois society? 82 04 AB6 Ch 4.11 4/2/08 11:22 AM Page 83 What are we learning in this chapter? Iroquois versus Haudenosaunee This chapter explores the social structure of Iroquois There are two names for society, which showed particular respect for women and the Iroquois people today: for people of other cultures. Iroquois (ear-o-kwa) and Haudenosaunee It also explores the structure and processes of Iroquois (how-den-o-show-nee). government. Think back to Chapter 3, where you saw how Iroquois is a name that the social structure of ancient Athens determined the way dates from the fur trade people participated in its government. -

Upper Canada, New York, and the Iroquois Six Nations, 1783-1815 Author(S): Alan Taylor Reviewed Work(S): Source: Journal of the Early Republic, Vol

Society for Historians of the Early American Republic The Divided Ground: Upper Canada, New York, and the Iroquois Six Nations, 1783-1815 Author(s): Alan Taylor Reviewed work(s): Source: Journal of the Early Republic, Vol. 22, No. 1 (Spring, 2002), pp. 55-75 Published by: University of Pennsylvania Press on behalf of the Society for Historians of the Early American Republic Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3124858 . Accessed: 02/11/2011 18:25 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of Pennsylvania Press and Society for Historians of the Early American Republic are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of the Early Republic. http://www.jstor.org THE DIVIDED GROUND: UPPER CANADA, NEW YORK, AND THE IROQUOIS SIX NATIONS, 1783-1815 AlanTaylor In recentyears, historians have paid increasing attention to bordersand borderlandsas fluidsites of bothnational formation and local contestation. At theirperipheries, nations and empires assert their power and define their identitywith no certainty of success.Nation-making and border-making are inseparablyintertwined. Nations and empires, however, often reap defiance frompeoples uneasily bisected by theimposed boundaries. This process of border-making(and border-defiance)has been especiallytangled in the Americaswhere empires and republicsprojected their ambitions onto a geographyoccupied and defined by Indians.Imperial or nationalvisions ran up against the tangled complexities of interdependentpeoples, both native and invader. -

The Protocols of Indian Treaties As Developed by Benjamin Franklin and Other Members of the American Philosophical Society

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Departmental Papers (Religious Studies) Department of Religious Studies 9-2015 How to Buy a Continent: The Protocols of Indian Treaties as Developed by Benjamin Franklin and Other Members of the American Philosophical Society Anthony F C Wallace University of Pennsylvania Timothy B. Powell University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/rs_papers Part of the Diplomatic History Commons, Religion Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Wallace, Anthony F C and Powell, Timothy B., "How to Buy a Continent: The Protocols of Indian Treaties as Developed by Benjamin Franklin and Other Members of the American Philosophical Society" (2015). Departmental Papers (Religious Studies). 15. https://repository.upenn.edu/rs_papers/15 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/rs_papers/15 For more information, please contact [email protected]. How to Buy a Continent: The Protocols of Indian Treaties as Developed by Benjamin Franklin and Other Members of the American Philosophical Society Abstract In 1743, when Benjamin Franklin announced the formation of an American Philosophical Society for the Promotion of Useful Knowledge, it was important for the citizens of Pennsylvania to know more about their American Indian neighbors. Beyond a slice of land around Philadelphia, three quarters of the province were still occupied by the Delaware and several other Indian tribes, loosely gathered under the wing of an Indian confederacy known as the Six Nations. Relations with the Six Nations and their allies were being peacefully conducted in a series of so-called “Indian Treaties” that dealt with the fur trade, threats of war with France, settlement of grievances, and the purchase of land. -

A Chronology of Edwards' Life and Writings

A CHRONOLOGY OF EDWARDS’ LIFE AND WRITINGS Compiled by Kenneth P. Minkema This chronology of Edwards's life and times is based on the dating of his early writings established by Thomas A. Schafer, Wallace E. Anderson, and Wilson H. Kimnach, supplemented by volume introductions in The Works of Jonathan Edwards, by primary sources dating from Edwards' lifetime, and by secondary materials such as biographies. Attributed dates for literary productions indicate the earliest or approximate points at which Edwards probably started them. "Miscellanies" entries are listed approximately in numerical groupings by year rather than chronologically; for more exact dating and order, readers should consult relevant volumes in the Edwards Works. Entries not preceded by a month indicates that the event in question occurred sometime during the calendar year under which it listed. Lack of a pronoun in a chronology entry indicates that it regards Edwards. 1703 October 5: born at East Windsor, Connecticut 1710 January 9: Sarah Pierpont born at New Haven, Connecticut 1711 August-September: Father Timothy serves as chaplain in Queen Anne's War; returns home early due to illness 1712 March-May: Awakening at East Windsor; builds prayer booth in swamp 1714 August: Queen Anne dies; King George I crowned November 22: Rev. James Pierpont, Sarah Pierpont's father, dies 1716 September: begins undergraduate studies at Connecticut Collegiate School, Wethersfield 2 1718 February 17: travels from East Windsor to Wethersfield following school “vacancy” October: moves to -

The Iroquois Confederacy Way of Making Decisions Was Different from That of the Ancient Greeks

76_ALB6SS_Ch4_F 2/13/08 3:37 PM Page 76 CHAPTER The Iroquois 4 Confederacy words matter! The Haudenosaunee [how-den-o-SHOW-nee] feel that they have a message about peace and the environment, Haudenosaunee is the name just as their ancestors did. In 1977, they made a speech to that the people of the Six Nations the United Nations (UN). This is part of it. call themselves. French settlers called them “Iroquois,” and historical documents also use “Iroquois.” Coming of the The United Nations is an organization that works for world Peacemaker peace. It builds cooperation “Haudenosaunee” is a word which means “people who among countries and protects build” and is the proper [traditional] name of the people the rights of people. Most of the Longhouse. The early history, before the Indo- countries, including Canada, Europeans came, explains that there was a time when belong to the United Nations. the peoples of the North American forest experienced war and strife. It was during such a time that there came into this land one who carried words of peace. That one would come to be called the Peacemaker. The Peacemaker came to the people with a message that human beings should cease abusing [hurting] one another. He stated that humans are capable of reason [thinking things through logically], that through that power of reason all men desire peace, and that it is necessary that the people organize to ensure that peace will be possible among the people who walk about on the earth. That was the original word about laws—laws were originally made to prevent the abuse [harming] of humans by other humans. -

June Session One Presentation

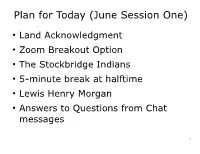

Plan for Today (June Session One) ● Land Acknowledgment ● Zoom Breakout Option ● The Stockbridge Indians ● 5-minute break at halftime ● Lewis Henry Morgan ● Answers to Questions from Chat messages 1 “Part 2” Fridays in June Greater detail on Algonkian culture and values ● Less emphasis on history, more emphasis on values, many of which persist to the present day ● Stories and Myths – Possible Guest Appearance(s) – Joseph Campbell's The Power of Myth ● Current/Recent Fiction 2 “Part 3” Fall OLLI Course Deeper dive into philosophy ● Cross-pollination (Interplay of European values and customs with those of the Native Americans) ● Comparison of the Theories of Balance ● Impact of the Little Ice Age ● Enlightenment Philosophers' misapprehension of prelapsarian “Primitives” ● Lessons learned and Opportunities lost ● Dealing with climate change, income inequality, and intellectual property ● Steady State Economics; Mutual Aid; DIY-bio 3 (biohacking) and much more Sources for Today (in addition to the two books recommended) ● Grace Bidwell Wilcox (1891-1968) ● Richard Bidwell Wilcox “John Trusler's Conversations with the Wappinger Chiefs on Civilization” c. 1810 ● Patrick Frazier The Mohicans of Stockbridge ● Daniel Noah Moses The Promise of Progress: The Life and Work of Lewis Henry Morgan 4 5 Indigenous Cultures Part 2 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus ● People arrived in the Americas earlier than had been thought ● There were many more people in the Americas than in previous estimates ● American cultures were far more sophisticated