Assessing the Availability, Service Quality, and Price of Essential Medicines In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Impact of a Changed Legislation on Reporting of Adverse Drug Reactions in Sweden, with Focus on Nurses Reporting

The impact of a changed legislation on reporting of adverse drug reactions in Sweden, with focus on nurses reporting Sofia A. Karlsson, Ingela Jacobsson, Marit Danell Boman, Katja M. Hakkarainen, Henrik Lövborg, Staffan Hägg and Anna K Jönsson Linköping University Post Print N.B.: When citing this work, cite the original article. The original publication is available at www.springerlink.com: Sofia A. Karlsson, Ingela Jacobsson, Marit Danell Boman, Katja M. Hakkarainen, Henrik Lövborg, Staffan Hägg and Anna K Jönsson, The impact of a changed legislation on reporting of adverse drug reactions in Sweden, with focus on nurses reporting, 2015, European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, (71), 5, 631-636. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00228-015-1839-6 Copyright: Springer Verlag (Germany) http://www.springerlink.com/?MUD=MP Postprint available at: Linköping University Electronic Press http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:liu:diva-118037 The impact of a changed legislation on reporting of adverse drug reactions in Sweden, with focus on nurses’ reporting Sofia A Karlsson1, Ingela Jacobsson2, Marit Danell Boman3, Katja M Hakkarainen4,5, Henrik Lövborg2, Staffan Hägg2,5, Anna K Jönsson2 Affiliations: 1. Department of Public Health and Community Medicine, the Sahlgrenska Academy at University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden 2. Department of Clinical Pharmacology and Department of Medical and Health Sciences, Linköping University, Linköping, Sweden 3. Division of Clinical Pharmacology, University Hospital of Umeå, Umeå, Sweden 4. Nordic School of -

Format (Sample) Dissertation

Providers’ Knowledge, Perceptions and Views of Prescribing Long-Acting Reversible Contraception to Adolescents in a Southwest Community Health Center Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Schafer, Stephanie Lynne Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 02/10/2021 06:38:23 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/626699 PROVIDERS’ KNOWLEDGE, PERCEPTIONS AND VIEWS OF PRESCRIBING LONG-ACTING REVERSIBLE CONTRACEPTION TO ADOLESCENTS IN A SOUTHWEST COMMUNITY HEALTH CENTER by Stephanie Lynne Schafer ________________________ Copyright © Stephanie Lynne Schafer 2017 A DNP Project Submitted to the Faculty of the COLLEGE OF NURSING In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF NURSING PRACTICE In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2 0 1 7 2 3 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This DNP Project has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this DNP Project are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his or her judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholarship. -

Injectable Birth Control May Raise HIV Infection Risk by 40%

08 January 2018 Injectable birth control may raise HIV infection risk by 40% The intramuscular injectable contraceptive depot medroxyprogesterone acetate, or DMPA, may raise the risk for HIV infection by 40% in women, according to research published recently in Endocrine Reviews. Research indicates alternative contraception methods may help protect women. Professor Janet P. Hapgood, lead author of the review from the University of Cape Town’s (UCT) Department of Molecular and Cell Biology said: “To protect individual and public health, it is important to ensure women in areas with high rates of HIV infection have access to affordable and safe contraceptive options.” In the review, researchers noted that the injectable progestin contraceptive, DMPA, is the major form of hormonal contraceptive used in sub-Saharan Africa, which also has the highest worldwide HIV prevalence, particularly in young women. However, researchers also noted that DMPA may raise the risk for HIV infection by 40% in women. “The increased rate of HIV infection among women using DMPA contraceptive shots is likely due to multiple reasons, including decreases in immune function, and the protective barrier function of the female genital tract. Studying the biology of medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) helps us understand what may be driving the increased rate of HIV infection seen in human research,” remarked Hapgood. Increasing the availability of contraceptives that use a different form of progestin than the one found in DMPA could help reduce the risk of HIV transmission. Other forms of contraception, including combined oral contraceptives containing levonorgestrel or the injectable contraceptive norethisterone enanthate (NET-EN), were not associated with increased HIV infection risk. -

Reseptregisteret 2013–2017 the Norwegian Prescription Database

LEGEMIDDELSTATISTIKK 2018:2 Reseptregisteret 2013–2017 Tema: Legemidler og eldre The Norwegian Prescription Database 2013–2017 Topic: Drug use in the elderly Reseptregisteret 2013–2017 Tema: Legemidler og eldre The Norwegian Prescription Database 2013–2017 Topic: Drug use in the elderly Christian Berg Hege Salvesen Blix Olaug Fenne Kari Furu Vidar Hjellvik Kari Jansdotter Husabø Irene Litleskare Marit Rønning Solveig Sakshaug Randi Selmer Anne-Johanne Søgaard Sissel Torheim Utgitt av Folkehelseinstituttet/Published by Norwegian Institute of Public Health Område for Helsedata og digitalisering Avdeling for Legemiddelstatistikk Juni 2018 Tittel/Title: Legemiddelstatistikk 2018:2 Reseptregisteret 2013–2017 / The Norwegian Prescription Database 2013–2017 Forfattere/Authors: Christian Berg, redaktør/editor Hege Salvesen Blix Olaug Fenne Kari Furu Vidar Hjellvik Kari Jansdotter Husabø Irene Litleskare Marit Rønning Solveig Sakshaug Randi Selmer Anne-Johanne Søgaard Sissel Torheim Acknowledgement: Julie D. W. Johansen (English text) Bestilling/Order: Rapporten kan lastes ned som pdf på Folkehelseinstituttets nettsider: www.fhi.no The report can be downloaded from www.fhi.no Grafisk design omslag: Fete Typer Ombrekking: Houston911 Kontaktinformasjon/Contact information: Folkehelseinstituttet/Norwegian Institute of Public Health Postboks 222 Skøyen N-0213 Oslo Tel: +47 21 07 70 00 ISSN: 1890-9647 ISBN: 978-82-8082-926-9 Sitering/Citation: Berg, C (red), Reseptregisteret 2013–2017 [The Norwegian Prescription Database 2013–2017] Legemiddelstatistikk 2018:2, Oslo, Norge: Folkehelseinstituttet, 2018. Tidligere utgaver / Previous editions: 2008: Reseptregisteret 2004–2007 / The Norwegian Prescription Database 2004–2007 2009: Legemiddelstatistikk 2009:2: Reseptregisteret 2004–2008 / The Norwegian Prescription Database 2004–2008 2010: Legemiddelstatistikk 2010:2: Reseptregisteret 2005–2009. Tema: Vanedannende legemidler / The Norwegian Prescription Database 2005–2009. -

COMPARISON of the WHO ATC CLASSIFICATION & Ephmra/Intellus Worldwide ANATOMICAL CLASSIFICATION

COMPARISON OF THE WHO ATC CLASSIFICATION & EphMRA/Intellus Worldwide ANATOMICAL CLASSIFICATION: VERSION June 2019 2 Comparison of the WHO ATC Classification and EphMRA / Intellus Worldwide Anatomical Classification The following booklet is designed to improve the understanding of the two classification systems. The development of the two systems had previously taken place separately. EphMRA and WHO are now working together to ensure that there is a convergence of the 2 systems rather than a divergence. In order to better understand the two classification systems, we should pay attention to the way in which substances/products are classified. WHO mainly classifies substances according to the therapeutic or pharmaceutical aspects and in one class only (particular formulations or strengths can be given separate codes, e.g. clonidine in C02A as antihypertensive agent, N02C as anti-migraine product and S01E as ophthalmic product). EphMRA classifies products, mainly according to their indications and use. Therefore, it is possible to find the same compound in several classes, depending on the product, e.g., NAPROXEN tablets can be classified in M1A (antirheumatic), N2B (analgesic) and G2C if indicated for gynaecological conditions only. The purposes of classification are also different: The main purpose of the WHO classification is for international drug utilisation research and for adverse drug reaction monitoring. This classification is recommended by the WHO for use in international drug utilisation research. The EphMRA/Intellus Worldwide classification has a primary objective to satisfy the marketing needs of the pharmaceutical companies. Therefore, a direct comparison is sometimes difficult due to the different nature and purpose of the two systems. -

Supplementary Appendix

Supplementary appendix Sipilä PN, Heikkilä N, Lindbohm JV, Hakulinen C, Vahtera J, Elovainio M, Suominen S, Väänänen A, Koskinen A, Nyberg ST, Pentti J, Strandberg TE, Kivimäki M. Hospital-treated infectious diseases and the risk of incident dementia: multicohort study with replication in the UK Biobank CONTENTS eFigure 1. Selection of participants in the study............................................................................... 2 eMethods 1. Study cohorts and data collection ................................................................................ 3 The Finnish Public Sector study (FPS)......................................................................................... 3 The Health and Social Support study (HeSSup) ........................................................................... 4 The Still Working study (STW) ................................................................................................... 5 The UK Biobank ......................................................................................................................... 5 eMethods 2. Proportionality of hazards ........................................................................................... 7 eFigure 2. Visualisation of hazard ratios over time using exponentiated scaled Schoenfeld residuals ....................................................................................................................................................... 8 eFigure 3. Dementia follow-up ..................................................................................................... -

![Ehealth DSI [Ehdsi V2.2.2-OR] Ehealth DSI – Master Value Set](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8870/ehealth-dsi-ehdsi-v2-2-2-or-ehealth-dsi-master-value-set-1028870.webp)

Ehealth DSI [Ehdsi V2.2.2-OR] Ehealth DSI – Master Value Set

MTC eHealth DSI [eHDSI v2.2.2-OR] eHealth DSI – Master Value Set Catalogue Responsible : eHDSI Solution Provider PublishDate : Wed Nov 08 16:16:10 CET 2017 © eHealth DSI eHDSI Solution Provider v2.2.2-OR Wed Nov 08 16:16:10 CET 2017 Page 1 of 490 MTC Table of Contents epSOSActiveIngredient 4 epSOSAdministrativeGender 148 epSOSAdverseEventType 149 epSOSAllergenNoDrugs 150 epSOSBloodGroup 155 epSOSBloodPressure 156 epSOSCodeNoMedication 157 epSOSCodeProb 158 epSOSConfidentiality 159 epSOSCountry 160 epSOSDisplayLabel 167 epSOSDocumentCode 170 epSOSDoseForm 171 epSOSHealthcareProfessionalRoles 184 epSOSIllnessesandDisorders 186 epSOSLanguage 448 epSOSMedicalDevices 458 epSOSNullFavor 461 epSOSPackage 462 © eHealth DSI eHDSI Solution Provider v2.2.2-OR Wed Nov 08 16:16:10 CET 2017 Page 2 of 490 MTC epSOSPersonalRelationship 464 epSOSPregnancyInformation 466 epSOSProcedures 467 epSOSReactionAllergy 470 epSOSResolutionOutcome 472 epSOSRoleClass 473 epSOSRouteofAdministration 474 epSOSSections 477 epSOSSeverity 478 epSOSSocialHistory 479 epSOSStatusCode 480 epSOSSubstitutionCode 481 epSOSTelecomAddress 482 epSOSTimingEvent 483 epSOSUnits 484 epSOSUnknownInformation 487 epSOSVaccine 488 © eHealth DSI eHDSI Solution Provider v2.2.2-OR Wed Nov 08 16:16:10 CET 2017 Page 3 of 490 MTC epSOSActiveIngredient epSOSActiveIngredient Value Set ID 1.3.6.1.4.1.12559.11.10.1.3.1.42.24 TRANSLATIONS Code System ID Code System Version Concept Code Description (FSN) 2.16.840.1.113883.6.73 2017-01 A ALIMENTARY TRACT AND METABOLISM 2.16.840.1.113883.6.73 2017-01 -

Innovative Practices Among Publicly Operated Family Planning Centers

Innovative Practices Among Publicly Operated Family Planning Centers COMPANION WORKBOOK Innovative Practices Among Publicly Operated Family Planning Centers COMPANION WORKBOOK Table of Contents CDPHE “Sustainability Coordinator” Job Description ................................................ 1 HCCMS Organizational History ............................................................................. 4 DHEC Regional Map ............................................................................................. 5 HCCMS Organizational Chart ............................................................................... 6 Sample Supply Requisition Sheet ............................................................................ 7 Sample Job Aid of Available Birth Control ............................................................... 9 Example Title X and FQHC Sliding Fee Scale ......................................................... 10 Example Guideline for Contraception ................................................................... 12 Example Contraception Wall Chart ....................................................................... 14 Example Clinical Guideline .................................................................................. 15 Sample Adolescent Services Policy ........................................................................ 17 South Carolina Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy Mission Statement ........................................................................ 19 “One Key Question” Educational -

Estonian Statistics on Medicines 2016 1/41

Estonian Statistics on Medicines 2016 ATC code ATC group / Active substance (rout of admin.) Quantity sold Unit DDD Unit DDD/1000/ day A ALIMENTARY TRACT AND METABOLISM 167,8985 A01 STOMATOLOGICAL PREPARATIONS 0,0738 A01A STOMATOLOGICAL PREPARATIONS 0,0738 A01AB Antiinfectives and antiseptics for local oral treatment 0,0738 A01AB09 Miconazole (O) 7088 g 0,2 g 0,0738 A01AB12 Hexetidine (O) 1951200 ml A01AB81 Neomycin+ Benzocaine (dental) 30200 pieces A01AB82 Demeclocycline+ Triamcinolone (dental) 680 g A01AC Corticosteroids for local oral treatment A01AC81 Dexamethasone+ Thymol (dental) 3094 ml A01AD Other agents for local oral treatment A01AD80 Lidocaine+ Cetylpyridinium chloride (gingival) 227150 g A01AD81 Lidocaine+ Cetrimide (O) 30900 g A01AD82 Choline salicylate (O) 864720 pieces A01AD83 Lidocaine+ Chamomille extract (O) 370080 g A01AD90 Lidocaine+ Paraformaldehyde (dental) 405 g A02 DRUGS FOR ACID RELATED DISORDERS 47,1312 A02A ANTACIDS 1,0133 Combinations and complexes of aluminium, calcium and A02AD 1,0133 magnesium compounds A02AD81 Aluminium hydroxide+ Magnesium hydroxide (O) 811120 pieces 10 pieces 0,1689 A02AD81 Aluminium hydroxide+ Magnesium hydroxide (O) 3101974 ml 50 ml 0,1292 A02AD83 Calcium carbonate+ Magnesium carbonate (O) 3434232 pieces 10 pieces 0,7152 DRUGS FOR PEPTIC ULCER AND GASTRO- A02B 46,1179 OESOPHAGEAL REFLUX DISEASE (GORD) A02BA H2-receptor antagonists 2,3855 A02BA02 Ranitidine (O) 340327,5 g 0,3 g 2,3624 A02BA02 Ranitidine (P) 3318,25 g 0,3 g 0,0230 A02BC Proton pump inhibitors 43,7324 A02BC01 Omeprazole -

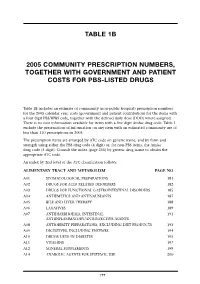

Table 1B 2005 Community Prescription Numbers, Together with Government

TABLE 1B 2005 COMMUNITY PRESCRIPTION NUMBERS, TOGETHER WITH GOVERNMENT AND PATIENT COSTS FOR PBS-LISTED DRUGS Table 1B includes an estimate of community (non-public hospital) prescription numbers for the 2005 calendar year, costs (government and patient contribution) for the items with a four digit PBS/RPBS code, together with the defined daily dose (DDD) where assigned. There is no cost information available for items with a five digit Amfac drug code. Table 1 exclude the presentation of information on any item with an estimated community use of less than 110 prescriptions in 2005. The prescription items are arranged by ATC code on generic name, and by form and strength using either the PBS drug code (4 digit) or, for non-PBS items, the Amfac drug code (5 digit). Consult the index (page 255) by generic drug name to obtain the appropriate ATC code. An index by 2nd level of the ATC classification follows: ALIMENTARY TRACT AND METABOLISM PAGE NO A01 STOMATOLOGICAL PREPARATIONS 181 A02 DRUGS FOR ACID RELATED DISORDERS 182 A03 DRUGS FOR FUNCTIONAL GASTROINTESTINAL DISORDERS 185 A04 ANTIEMETICS AND ANTINAUSEANTS 187 A05 BILE AND LIVER THERAPY 188 A06 LAXATIVES 189 A07 ANTIDIARRHOEALS, INTESTINAL 191 ANTIINFLAMMATORY/ANTIINFECTIVE AGENTS A08 ANTIOBESITY PREPARATIONS, EXCLUDING DIET PRODUCTS 193 A09 DIGESTIVES, INCLUDING ENZYMES 194 A10 DRUGS USED IN DIABETES 195 A11 VITAMINS 197 A12 MINERAL SUPPLEMENTS 199 A14 ANABOLIC AGENTS FOR SYSTEMIC USE 200 177 BLOOD AND BLOOD FORMING ORGANS B01 ANTITHROMBOTIC AGENTS 201 B02 ANTIHAEMORRHAGICS 203 B03 -

The Effects of Hormonal Contraception on the Voice: History of Its Evolution in the Literature

CARE OF THE PROFESSIONAL VOICE Robert T. Sataloff, Associate Editor The Effects of Hormonal Contraception on the Voice: History of its Evolution in the Literature Jennifer Rodney and Robert T. Sataloff [Modified from J. Rodney and R.T. Sataloff, “The Effects of Hormonal Contraception on the Voice: History of its Evolution in the Literature,” Journal of Voice 30, no. 6 (November 2016): 726–730; with permission.] INTRODUCTION: THE MENSTRUAL CYCLE AND THE VOICE The fluctuation of hormones in the menstrual cycle has significant effects on the voice.1 Singing teachers should be familiar with the vocal effects of Jennifer Rodney hormones and of hormonal medications such as oral contraceptives (birth control pills), especially in light of recent changes in their chemistry and effects. Vocal symptoms, known as dysphonia premenstrualis, accompany the better known symptoms of premenstrual syndrome (PMS) during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle.2 The most common symptoms of dys- phonia premenstrualis are difficulty singing high notes, decreased flexibil- ity, huskiness, fuzziness, breathiness, decreased volume, difficulty bridging passaggios and intonation problems.3 Davis and Davis concluded that, on average, singers experience 33 general symptoms of PMS and 3 symptoms of dysphonia premenstrualis.4 Chae et al. showed that approximately 57% participants met the DSM IV criteria for PMS and also had acoustic evidence Robert T. Sataloff of dysphonia premenstrualis, whereas the PMS-negative group did not.5 The risk of vocal stress and possible damage during the premenstrual period led many European opera houses to offer singers contracts that included “grace days” during their premenstrual period. This accommodation is no longer followed in Europe and was never practiced generally in the United States.6 The mechanisms that cause these symptoms lie not just in the actions of the hormones themselves, but also in the cyclic fluctuation of hormone levels. -

Contraception in Adolescents – Regulatory Considerations”

“Contraception in adolescents – regulatory considerations” Wissenschaftliche Prüfungsarbeit zur Erlangung des Titels „Master of Drug Regulatory Affairs“ der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn vorgelegt von Dr. Julian Paesler aus Münster Bonn 2016 Betreuerin und 1. Referentin: Frau Dr. Ingrid Klingmann Zweiter Referent: Herr Prof. Dr. Niels Eckstein Acknowledgements I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Dr. Ingrid Klingmann for her friendly willingness to function as my “supervising tutor” and for the support and the motivating feedback she gave me during the preparation of this master thesis. Her comments and constructive suggestions were very helpful to me. Besides Dr. Ingrid Klingmann, I would like to thank Prof. Dr. Niels Eckstein for his support and the willingness to function as my “secondary tutor”. Special thanks are also due to my mother, who was willing to proofread this master thesis. I am really thankful for all the support she gave - and still gives – to me, which is way more than what could ever be mentioned here. Table of Contents Table of Contents List of Figures .......................................................................................................................... I List of Tables ......................................................................................................................... III List of Abbreviations ..............................................................................................................