The Impact of a Changed Legislation on Reporting of Adverse Drug Reactions in Sweden, with Focus on Nurses Reporting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Assessing the Availability, Service Quality, and Price of Essential Medicines In

Assessing the Availability, Service Quality, and Price of Essential Medicines in Private Pharmacies in Afghanistan Norio Kasahara A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2015 Reading Committee: Louis P. Garrison, Jr., Chair Joseph B. Babigumira Andy Stergachis Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Pharmaceutical Outcomes Research and Policy ©Copyright 2015 Norio Kasahara ii Table of Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................................................................................... ................................................................................................ ................................................................................................ .................................................................................. ............... vvv Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................................................................... ................................................................................................ ................................................................................. ............ viiviivii Summary ................................................................................................................................................................................... ............................................................................................... -

Reseptregisteret 2013–2017 the Norwegian Prescription Database

LEGEMIDDELSTATISTIKK 2018:2 Reseptregisteret 2013–2017 Tema: Legemidler og eldre The Norwegian Prescription Database 2013–2017 Topic: Drug use in the elderly Reseptregisteret 2013–2017 Tema: Legemidler og eldre The Norwegian Prescription Database 2013–2017 Topic: Drug use in the elderly Christian Berg Hege Salvesen Blix Olaug Fenne Kari Furu Vidar Hjellvik Kari Jansdotter Husabø Irene Litleskare Marit Rønning Solveig Sakshaug Randi Selmer Anne-Johanne Søgaard Sissel Torheim Utgitt av Folkehelseinstituttet/Published by Norwegian Institute of Public Health Område for Helsedata og digitalisering Avdeling for Legemiddelstatistikk Juni 2018 Tittel/Title: Legemiddelstatistikk 2018:2 Reseptregisteret 2013–2017 / The Norwegian Prescription Database 2013–2017 Forfattere/Authors: Christian Berg, redaktør/editor Hege Salvesen Blix Olaug Fenne Kari Furu Vidar Hjellvik Kari Jansdotter Husabø Irene Litleskare Marit Rønning Solveig Sakshaug Randi Selmer Anne-Johanne Søgaard Sissel Torheim Acknowledgement: Julie D. W. Johansen (English text) Bestilling/Order: Rapporten kan lastes ned som pdf på Folkehelseinstituttets nettsider: www.fhi.no The report can be downloaded from www.fhi.no Grafisk design omslag: Fete Typer Ombrekking: Houston911 Kontaktinformasjon/Contact information: Folkehelseinstituttet/Norwegian Institute of Public Health Postboks 222 Skøyen N-0213 Oslo Tel: +47 21 07 70 00 ISSN: 1890-9647 ISBN: 978-82-8082-926-9 Sitering/Citation: Berg, C (red), Reseptregisteret 2013–2017 [The Norwegian Prescription Database 2013–2017] Legemiddelstatistikk 2018:2, Oslo, Norge: Folkehelseinstituttet, 2018. Tidligere utgaver / Previous editions: 2008: Reseptregisteret 2004–2007 / The Norwegian Prescription Database 2004–2007 2009: Legemiddelstatistikk 2009:2: Reseptregisteret 2004–2008 / The Norwegian Prescription Database 2004–2008 2010: Legemiddelstatistikk 2010:2: Reseptregisteret 2005–2009. Tema: Vanedannende legemidler / The Norwegian Prescription Database 2005–2009. -

Supplementary Appendix

Supplementary appendix Sipilä PN, Heikkilä N, Lindbohm JV, Hakulinen C, Vahtera J, Elovainio M, Suominen S, Väänänen A, Koskinen A, Nyberg ST, Pentti J, Strandberg TE, Kivimäki M. Hospital-treated infectious diseases and the risk of incident dementia: multicohort study with replication in the UK Biobank CONTENTS eFigure 1. Selection of participants in the study............................................................................... 2 eMethods 1. Study cohorts and data collection ................................................................................ 3 The Finnish Public Sector study (FPS)......................................................................................... 3 The Health and Social Support study (HeSSup) ........................................................................... 4 The Still Working study (STW) ................................................................................................... 5 The UK Biobank ......................................................................................................................... 5 eMethods 2. Proportionality of hazards ........................................................................................... 7 eFigure 2. Visualisation of hazard ratios over time using exponentiated scaled Schoenfeld residuals ....................................................................................................................................................... 8 eFigure 3. Dementia follow-up ..................................................................................................... -

![Ehealth DSI [Ehdsi V2.2.2-OR] Ehealth DSI – Master Value Set](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8870/ehealth-dsi-ehdsi-v2-2-2-or-ehealth-dsi-master-value-set-1028870.webp)

Ehealth DSI [Ehdsi V2.2.2-OR] Ehealth DSI – Master Value Set

MTC eHealth DSI [eHDSI v2.2.2-OR] eHealth DSI – Master Value Set Catalogue Responsible : eHDSI Solution Provider PublishDate : Wed Nov 08 16:16:10 CET 2017 © eHealth DSI eHDSI Solution Provider v2.2.2-OR Wed Nov 08 16:16:10 CET 2017 Page 1 of 490 MTC Table of Contents epSOSActiveIngredient 4 epSOSAdministrativeGender 148 epSOSAdverseEventType 149 epSOSAllergenNoDrugs 150 epSOSBloodGroup 155 epSOSBloodPressure 156 epSOSCodeNoMedication 157 epSOSCodeProb 158 epSOSConfidentiality 159 epSOSCountry 160 epSOSDisplayLabel 167 epSOSDocumentCode 170 epSOSDoseForm 171 epSOSHealthcareProfessionalRoles 184 epSOSIllnessesandDisorders 186 epSOSLanguage 448 epSOSMedicalDevices 458 epSOSNullFavor 461 epSOSPackage 462 © eHealth DSI eHDSI Solution Provider v2.2.2-OR Wed Nov 08 16:16:10 CET 2017 Page 2 of 490 MTC epSOSPersonalRelationship 464 epSOSPregnancyInformation 466 epSOSProcedures 467 epSOSReactionAllergy 470 epSOSResolutionOutcome 472 epSOSRoleClass 473 epSOSRouteofAdministration 474 epSOSSections 477 epSOSSeverity 478 epSOSSocialHistory 479 epSOSStatusCode 480 epSOSSubstitutionCode 481 epSOSTelecomAddress 482 epSOSTimingEvent 483 epSOSUnits 484 epSOSUnknownInformation 487 epSOSVaccine 488 © eHealth DSI eHDSI Solution Provider v2.2.2-OR Wed Nov 08 16:16:10 CET 2017 Page 3 of 490 MTC epSOSActiveIngredient epSOSActiveIngredient Value Set ID 1.3.6.1.4.1.12559.11.10.1.3.1.42.24 TRANSLATIONS Code System ID Code System Version Concept Code Description (FSN) 2.16.840.1.113883.6.73 2017-01 A ALIMENTARY TRACT AND METABOLISM 2.16.840.1.113883.6.73 2017-01 -

Estonian Statistics on Medicines 2016 1/41

Estonian Statistics on Medicines 2016 ATC code ATC group / Active substance (rout of admin.) Quantity sold Unit DDD Unit DDD/1000/ day A ALIMENTARY TRACT AND METABOLISM 167,8985 A01 STOMATOLOGICAL PREPARATIONS 0,0738 A01A STOMATOLOGICAL PREPARATIONS 0,0738 A01AB Antiinfectives and antiseptics for local oral treatment 0,0738 A01AB09 Miconazole (O) 7088 g 0,2 g 0,0738 A01AB12 Hexetidine (O) 1951200 ml A01AB81 Neomycin+ Benzocaine (dental) 30200 pieces A01AB82 Demeclocycline+ Triamcinolone (dental) 680 g A01AC Corticosteroids for local oral treatment A01AC81 Dexamethasone+ Thymol (dental) 3094 ml A01AD Other agents for local oral treatment A01AD80 Lidocaine+ Cetylpyridinium chloride (gingival) 227150 g A01AD81 Lidocaine+ Cetrimide (O) 30900 g A01AD82 Choline salicylate (O) 864720 pieces A01AD83 Lidocaine+ Chamomille extract (O) 370080 g A01AD90 Lidocaine+ Paraformaldehyde (dental) 405 g A02 DRUGS FOR ACID RELATED DISORDERS 47,1312 A02A ANTACIDS 1,0133 Combinations and complexes of aluminium, calcium and A02AD 1,0133 magnesium compounds A02AD81 Aluminium hydroxide+ Magnesium hydroxide (O) 811120 pieces 10 pieces 0,1689 A02AD81 Aluminium hydroxide+ Magnesium hydroxide (O) 3101974 ml 50 ml 0,1292 A02AD83 Calcium carbonate+ Magnesium carbonate (O) 3434232 pieces 10 pieces 0,7152 DRUGS FOR PEPTIC ULCER AND GASTRO- A02B 46,1179 OESOPHAGEAL REFLUX DISEASE (GORD) A02BA H2-receptor antagonists 2,3855 A02BA02 Ranitidine (O) 340327,5 g 0,3 g 2,3624 A02BA02 Ranitidine (P) 3318,25 g 0,3 g 0,0230 A02BC Proton pump inhibitors 43,7324 A02BC01 Omeprazole -

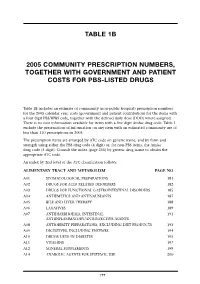

Table 1B 2005 Community Prescription Numbers, Together with Government

TABLE 1B 2005 COMMUNITY PRESCRIPTION NUMBERS, TOGETHER WITH GOVERNMENT AND PATIENT COSTS FOR PBS-LISTED DRUGS Table 1B includes an estimate of community (non-public hospital) prescription numbers for the 2005 calendar year, costs (government and patient contribution) for the items with a four digit PBS/RPBS code, together with the defined daily dose (DDD) where assigned. There is no cost information available for items with a five digit Amfac drug code. Table 1 exclude the presentation of information on any item with an estimated community use of less than 110 prescriptions in 2005. The prescription items are arranged by ATC code on generic name, and by form and strength using either the PBS drug code (4 digit) or, for non-PBS items, the Amfac drug code (5 digit). Consult the index (page 255) by generic drug name to obtain the appropriate ATC code. An index by 2nd level of the ATC classification follows: ALIMENTARY TRACT AND METABOLISM PAGE NO A01 STOMATOLOGICAL PREPARATIONS 181 A02 DRUGS FOR ACID RELATED DISORDERS 182 A03 DRUGS FOR FUNCTIONAL GASTROINTESTINAL DISORDERS 185 A04 ANTIEMETICS AND ANTINAUSEANTS 187 A05 BILE AND LIVER THERAPY 188 A06 LAXATIVES 189 A07 ANTIDIARRHOEALS, INTESTINAL 191 ANTIINFLAMMATORY/ANTIINFECTIVE AGENTS A08 ANTIOBESITY PREPARATIONS, EXCLUDING DIET PRODUCTS 193 A09 DIGESTIVES, INCLUDING ENZYMES 194 A10 DRUGS USED IN DIABETES 195 A11 VITAMINS 197 A12 MINERAL SUPPLEMENTS 199 A14 ANABOLIC AGENTS FOR SYSTEMIC USE 200 177 BLOOD AND BLOOD FORMING ORGANS B01 ANTITHROMBOTIC AGENTS 201 B02 ANTIHAEMORRHAGICS 203 B03 -

Drug Consumption in Current Year (Period 201901

Page 1 Drug consumption in current year (Period 202001 - 202012) Wholesale ATC code Subgroup or chemical substance DDD/1000 inhab./day Hospital % Change % price/1000 € Hospital % Change % A ALIMENTARY TRACT AND METABOLISM 323,80 3 4 321 589 7 4 A01 STOMATOLOGICAL PREPARATIONS 14,28 4 12 2 090 9 8 A01A STOMATOLOGICAL PREPARATIONS 14,28 4 12 2 090 9 8 A01AA Caries prophylactic agents 11,90 3 14 663 8 9 A01AA01 sodium fluoride 11,90 3 14 610 8 10 A01AA03 olaflur - - - 53 1 -2 A01AB Antiinfectives for local oral treatment 2,36 8 2 1 266 10 15 A01AB03 chlorhexidine 2,02 6 -3 930 6 5 A01AB11 various 0,33 21 57 335 21 55 A01AB22 doxycycline - - - 0 - -100 A01AC Corticosteroids for local oral treatment - - - 113 1 -26 A01AC01 triamcinolone - - - 113 1 -26 A01AD Other agents for local oral treatment 0,02 0 -28 49 0 -32 A01AD02 benzydamine 0,02 0 -28 49 0 -32 A02 DRUGS FOR ACID RELATED DISORDERS 73,05 3 3 30 885 4 -5 A02A ANTACIDS 2,23 1 1 3 681 1 3 A02AA Magnesium compounds 0,07 22 -7 141 22 -7 A02AA04 magnesium hydroxide 0,07 22 -7 141 22 -7 A02AD Combinations and complexes of aluminium, 2,17 0 1 3 539 0 4 calcium and magnesium compounds A02AD01 ordinary salt combinations 2,17 0 1 3 539 0 4 A02B DRUGS FOR PEPTIC ULCER AND 70,82 3 3 27 205 5 -7 GASTRO-OESOPHAGEAL REFLUX DISEASE (GORD) A02BA H2-receptor antagonists 0,17 7 -77 551 10 -29 A02BA02 ranitidine 0,00 1 -100 1 1 -100 A02BA03 famotidine 0,16 7 48 550 10 43 A02BB Prostaglandins 0,04 62 55 80 62 55 A02BB01 misoprostol 0,04 62 55 80 62 55 A02BC Proton pump inhibitors 69,26 3 4 23 531 4 -8 -

Drug Consumption at Wholesale Prices in 2017 - 2020

Page 1 Drug consumption at wholesale prices in 2017 - 2020 2020 2019 2018 2017 Wholesale Hospit. Wholesale Hospit. Wholesale Hospit. Wholesale Hospit. ATC code Subgroup or chemical substance price/1000 € % price/1000 € % price/1000 € % price/1000 € % A ALIMENTARY TRACT AND METABOLISM 321 590 7 309 580 7 300 278 7 295 060 8 A01 STOMATOLOGICAL PREPARATIONS 2 090 9 1 937 7 1 910 7 2 128 8 A01A STOMATOLOGICAL PREPARATIONS 2 090 9 1 937 7 1 910 7 2 128 8 A01AA Caries prophylactic agents 663 8 611 11 619 12 1 042 11 A01AA01 sodium fluoride 610 8 557 12 498 15 787 14 A01AA03 olaflur 53 1 54 1 50 1 48 1 A01AA51 sodium fluoride, combinations - - - - 71 1 206 1 A01AB Antiinfectives for local oral treatment 1 266 10 1 101 6 1 052 6 944 6 A01AB03 chlorhexidine 930 6 885 7 825 7 706 7 A01AB11 various 335 21 216 0 227 0 238 0 A01AB22 doxycycline - - 0 100 0 100 - - A01AC Corticosteroids for local oral treatment 113 1 153 1 135 1 143 1 A01AC01 triamcinolone 113 1 153 1 135 1 143 1 A01AD Other agents for local oral treatment 49 0 72 0 104 0 - - A01AD02 benzydamine 49 0 72 0 104 0 - - A02 DRUGS FOR ACID RELATED DISORDERS 30 885 4 32 677 4 35 102 5 37 644 7 A02A ANTACIDS 3 681 1 3 565 1 3 357 1 3 385 1 A02AA Magnesium compounds 141 22 151 22 172 22 155 19 A02AA04 magnesium hydroxide 141 22 151 22 172 22 155 19 A02AD Combinations and complexes of aluminium, 3 539 0 3 414 0 3 185 0 3 231 0 calcium and magnesium compounds A02AD01 ordinary salt combinations 3 539 0 3 414 0 3 185 0 3 231 0 A02B DRUGS FOR PEPTIC ULCER AND 27 205 5 29 112 4 31 746 5 34 258 8 -

Estonian Statistics on Medicines 2013 1/44

Estonian Statistics on Medicines 2013 DDD/1000/ ATC code ATC group / INN (rout of admin.) Quantity sold Unit DDD Unit day A ALIMENTARY TRACT AND METABOLISM 146,8152 A01 STOMATOLOGICAL PREPARATIONS 0,0760 A01A STOMATOLOGICAL PREPARATIONS 0,0760 A01AB Antiinfectives and antiseptics for local oral treatment 0,0760 A01AB09 Miconazole(O) 7139,2 g 0,2 g 0,0760 A01AB12 Hexetidine(O) 1541120 ml A01AB81 Neomycin+Benzocaine(C) 23900 pieces A01AC Corticosteroids for local oral treatment A01AC81 Dexamethasone+Thymol(dental) 2639 ml A01AD Other agents for local oral treatment A01AD80 Lidocaine+Cetylpyridinium chloride(gingival) 179340 g A01AD81 Lidocaine+Cetrimide(O) 23565 g A01AD82 Choline salicylate(O) 824240 pieces A01AD83 Lidocaine+Chamomille extract(O) 317140 g A01AD86 Lidocaine+Eugenol(gingival) 1128 g A02 DRUGS FOR ACID RELATED DISORDERS 35,6598 A02A ANTACIDS 0,9596 Combinations and complexes of aluminium, calcium and A02AD 0,9596 magnesium compounds A02AD81 Aluminium hydroxide+Magnesium hydroxide(O) 591680 pieces 10 pieces 0,1261 A02AD81 Aluminium hydroxide+Magnesium hydroxide(O) 1998558 ml 50 ml 0,0852 A02AD82 Aluminium aminoacetate+Magnesium oxide(O) 463540 pieces 10 pieces 0,0988 A02AD83 Calcium carbonate+Magnesium carbonate(O) 3049560 pieces 10 pieces 0,6497 A02AF Antacids with antiflatulents Aluminium hydroxide+Magnesium A02AF80 1000790 ml hydroxide+Simeticone(O) DRUGS FOR PEPTIC ULCER AND GASTRO- A02B 34,7001 OESOPHAGEAL REFLUX DISEASE (GORD) A02BA H2-receptor antagonists 3,5364 A02BA02 Ranitidine(O) 494352,3 g 0,3 g 3,5106 A02BA02 Ranitidine(P) -

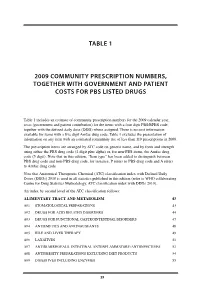

Table 1 2009 Community Prescription Numbers

TABLE 1 2009 COMMUNITY PRESCRIPTION NUMBERS, TOGETHER WITH GOVERNMENT AND PATIENT COSTS FOR PBS LISTED DRUGS Table 1 includes an estimate of community prescription numbers for the 2009 calendar year, costs (government and patient contribution) for the items with a four digit PBS/RPBS code, together with the defined daily dose (DDD) where assigned. There is no cost information available for items with a five digit Amfac drug code. Table 1 excludes the presentation of information on any item with an estimated community use of less than 110 prescriptions in 2009. The prescription items are arranged by ATC code on generic name, and by form and strength using either the PBS drug code (4 digit plus alpha) or, for non-PBS items, the Amfac drug code (5 digit). Note that in this edition, “Item type” has been added to distinguish between PBS drug code and non-PBS drug code, for instance, P refers to PBS drug code and A refers to Amfac drug code. Note that Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification index with Defined Daily Doses (DDDs) 2010 is used in all statistics published in this edition (refer to WHO collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology, ATC classification index with DDDs 2010). An index by second level of the ATC classification follows: ALIMENTARY TRACT AND METABOLISM 43 A01 STOMATOLOGICAL PREPARATIONS 43 A02 DRUGS FOR ACID RELATED DISORDERS 44 A03 DRUGS FOR FUNCTIONAL GASTROINTESTINAL DISORDERS 47 A04 ANTIEMETICS AND ANTINAUSEANTS 48 A05 BILE AND LIVER THERAPY 49 A06 LAXATIVES 51 A07 ANTIDIARRHOEALS, INTESTINAL ANTIINFLAMMATORY/ANTIINFECTIVES -

Table 1 2008 Community Prescription Numbers

TABLE 1 2008 COMMUNITY PRESCRIPTION NUMBERS, TOGETHER WITH GOVERNMENT AND PATIENT COSTS FOR PBS-LISTED DRUGS Table 1 includes an estimate of community prescription numbers for the 2008 calendar year, costs (government and patient contribution) for the items with a four digit PBS/RPBS code, together with the defined daily dose (DDD) where assigned. There is no cost information available for items with a five digit Amfac drug code. Table 1 excludes the presentation of information on any item with an estimated community use of less than 110 prescriptions in 2008. The prescription items are arranged by ATC code on generic name, and by form and strength using either the PBS drug code (4 digit plus alpha) or, for non-PBS items, the Amfac drug code (5 digit). Note that in this edition, “Item type” has been added to distinguish between PBS drug code and non-PBS drug code, for instance, P refers to PBS drug code and A refers to Amfac drug code. Note that Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification index with Defined Daily Doses (DDDs) 2009 is used in all statistics published in this edition (refer to WHO collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology, ATC classification index with DDDs 2009). An index by 2nd level of the ATC classification follows: ALIMENTARY TRACT AND METABOLISM PAGE NO A01 STOMATOLOGICAL PREPARATIONS 41 A02 DRUGS FOR ACID RELATED DISORDERS 42 A03 DRUGS FOR FUNCTIONAL GASTROINTESTINAL DISORDERS 44 A04 ANTIEMETICS AND ANTINAUSEANTS 45 A05 BILE AND LIVER THERAPY 46 A06 LAXATIVES 47 A07 ANTIDIARRHOEALS, INTESTINAL -

Instruction Manual Part 2B 2010

TABLE OF CONTENTS Page SECTION I – INTRODUCTION A. Introduction ........................................................................................ 1 Major Revisions from Previous Manuals ............................................. 4 B. Medical Certification .......................................................................... 8 Excerpt from U.S. Standard Certificate of Death ................................ 9 U.S. Standard Certificate of Death ....................................................... 10 SECTION II – GENERAL INSTRUCTIONS A. Introduction......................................................................................... 13 1. Excessive Codes ........................................................................... 13 2. Created Codes .............................................................................. 15 3. “Dagger and asterisk” codes ........................................................ 26 B. General coding concept ..................................................................... 27 1. Definitions and types of diagnostic entities .................................. 27 a. One-term entity ........................................................................ 27 b. Multiple one-term entity .......................................................... 29 c. Adjectival modifier reported with multiple conditions ........... 31 2. Parenthe tical entries ...................................................................... 32 3. Special diagnostic entities ............................................................