Bhagavad Gita Is Perhaps the Most Famous Text in Indian Philosophy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mahabharata

^«/4 •m ^1 m^m^ The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924071123131 ) THE MAHABHARATA OF KlUSHNA-DWAIPAYANA VTASA TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH PROSE. Published and distributed, chiefly gratis, BY PROTSP CHANDRA EOY. BHISHMA PARVA. CALCUTTA i BHiRATA PRESS. No, 1, Raja Gooroo Dass' Stbeet, Beadon Square, 1887. ( The righi of trmsMm is resem^. NOTICE. Having completed the Udyoga Parva I enter the Bhishma. The preparations being completed, the battle must begin. But how dan- gerous is the prospect ahead ? How many of those that were counted on the eve of the terrible conflict lived to see the overthrow of the great Knru captain ? To a KsJtatriya warrior, however, the fiercest in- cidents of battle, instead of being appalling, served only as tests of bravery that opened Heaven's gates to him. It was this belief that supported the most insignificant of combatants fighting on foot when they rushed against Bhishma, presenting their breasts to the celestial weapons shot by him, like insects rushing on a blazing fire. I am not a Kshatriya. The prespect of battle, therefore, cannot be unappalling or welcome to me. On the other hand, I frankly own that it is appall- ing. If I receive support, that support may encourage me. I am no Garuda that I would spurn the strength of number* when battling against difficulties. I am no Arjuna conscious of superhuman energy and aided by Kecava himself so that I may eHcounter any odds. -

Väkivallan Muodot Ja Sen Kuvaamisen Keinot Arundhati Royn Teoksessa the God of Small Things Ja Bernardine Evariston Runoromaanissa the Emperor’S Babe

TAMPEREEN YLIOPISTO Raisa Aho Miten kertoa kivusta? Väkivallan muodot ja sen kuvaamisen keinot Arundhati Royn teoksessa The God of Small Things ja Bernardine Evariston runoromaanissa The Emperor’s Babe Yleisen kirjallisuustieteen pro gradu -tutkielma Tampere 2011 Tampereen yliopisto, Kieli-, käännös- ja kirjallisuustieteiden yksikkö AHO, Raisa: Miten kertoa kivusta? Väkivallan muodot ja sen kuvaamisen keinot Arundhati Royn romaanissa The God of Small Things ja Bernardine Evariston runoteoksessa The Emperor’s Babe Pro Gradu -tutkielma, 128 s. Yleinen kirjallisuustiede Huhtikuu 2011 Yleisen kirjallisuustieteen pro gradu -tutkielmassani tarkastelen erilaisia väkivallan ilmenemismuotoja ja niiden kuvaamisen keinoja kahdessa kaunokirjallisessa teoksessa, eli Arundhati Royn romaanissa The God of Small Things (1997) ja Bernardine Evariston runoromaanissa The Emperor’s Babe (2001). Päädyin tarkastelemaan juuri näitä kahta teosta rinnakkain sekä sisällöllisistä, temaattisista, kirjallisuushistoriallisista että kerronnallisista syistä. Ne molemmat kuuluvat niin sanotun postkoloniaalisen kirjallisuuden traditioon, mutta eri tavoilla. Molemmissa käsitellään väkivaltaa ja sen traumatisoivaa luonnetta, mutta kertojaratkaisujen erot tuovat väkivallan kuvauksiin erilaisia painotuksia. Tutkimukseni lähtee liikkeelle sekä ruumiillisen kivun että traumaattisen kokemuksen kieltä pakenevasta luonteesta. Molempia ilmiöitä on tarkasteltu siitä lähtökohdasta, että ne ovat symboloimattomia, ja niiden sanoiksi pukeminen on vaikeaa, ellei peräti mahdotonta. Kivun -

The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa SALYA

The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa SALYA PARVA translated by Kesari Mohan Ganguli In parentheses Publications Sanskrit Series Cambridge, Ontario 2002 Salya Parva Section I Om! Having bowed down unto Narayana and Nara, the most exalted of male beings, and the goddess Saraswati, must the word Jaya be uttered. Janamejaya said, “After Karna had thus been slain in battle by Savyasachin, what did the small (unslaughtered) remnant of the Kauravas do, O regenerate one? Beholding the army of the Pandavas swelling with might and energy, what behaviour did the Kuru prince Suyodhana adopt towards the Pandavas, thinking it suitable to the hour? I desire to hear all this. Tell me, O foremost of regenerate ones, I am never satiated with listening to the grand feats of my ancestors.” Vaisampayana said, “After the fall of Karna, O king, Dhritarashtra’s son Suyodhana was plunged deep into an ocean of grief and saw despair on every side. Indulging in incessant lamentations, saying, ‘Alas, oh Karna! Alas, oh Karna!’ he proceeded with great difficulty to his camp, accompanied by the unslaughtered remnant of the kings on his side. Thinking of the slaughter of the Suta’s son, he could not obtain peace of mind, though comforted by those kings with excellent reasons inculcated by the scriptures. Regarding destiny and necessity to be all- powerful, the Kuru king firmly resolved on battle. Having duly made Salya the generalissimo of his forces, that bull among kings, O monarch, proceeded for battle, accompanied by that unslaughtered remnant of his forces. Then, O chief of Bharata’s race, a terrible battle took place between the troops of the Kurus and those of the Pandavas, resembling that between the gods and the Asuras. -

Janmashtami Commemorative Service Reading Volume II

Janmashtami Commemorative Service Reading Volume II Commemorative Service Readings Please use the reading from the volume appropriate for the year in which you are reading. The volume number of the commemorative service readings must match the volume number of the Sunday service readings. There are two colors of font — black and blue. Black indicates a section created by the reader as an introduction, transition, or summary. These may be altered to suit your reading style. Blue indicates material taken from an SRF sources, such as Autobiography of a Yogi, Mejda, Self-Realization Magazine, etc. These are not to be changed. If you find an error, please notify the chairperson of the readers' committee for correction. At the end of quoted material there is usually the source and page number from which the material is taken. This is for your information only and is not to be read. Janmashtami Reading Volume II Our reading this evening is taken from the SRF publication The Yoga of the Bhagavad Gita. Lord Krishna was born in a prison. Shortly after his birth, he was smuggled out of jail and given to foster parents, where he passed his childhood as a humble cowherd near Brindaban on the banks of the Yamuna River. He was hardly more than a boy when it came time for him to leave Brindaban to fulfill the purpose of his incarnation: to assist the virtuous in restraining evil. Of kingly birth, as an adult Sri Krishna performed his kingly duties, engaging in many campaigns against the reigns of evil rulers. Much of his life is intertwined with that of the Pandavas, the family of Arjuna, and their cousins the Kauravas. -

The Mahabharata

VivekaVani - Voice of Vivekananda THE MAHABHARATA (Delivered by Swami Vivekananda at the Shakespeare Club, Pasadena, California, February 1, 1900) The other epic about which I am going to speak to you this evening, is called the Mahâbhârata. It contains the story of a race descended from King Bharata, who was the son of Dushyanta and Shakuntalâ. Mahâ means great, and Bhârata means the descendants of Bharata, from whom India has derived its name, Bhârata. Mahabharata means Great India, or the story of the great descendants of Bharata. The scene of this epic is the ancient kingdom of the Kurus, and the story is based on the great war which took place between the Kurus and the Panchâlas. So the region of the quarrel is not very big. This epic is the most popular one in India; and it exercises the same authority in India as Homer's poems did over the Greeks. As ages went on, more and more matter was added to it, until it has become a huge book of about a hundred thousand couplets. All sorts of tales, legends and myths, philosophical treatises, scraps of history, and various discussions have been added to it from time to time, until it is a vast, gigantic mass of literature; and through it all runs the old, original story. The central story of the Mahabharata is of a war between two families of cousins, one family, called the Kauravas, the other the Pândavas — for the empire of India. The Aryans came into India in small companies. Gradually, these tribes began to extend, until, at last, they became the undisputed rulers of India. -

When Blind Love for Kin Precedes Bounden Duty to Kingdom- a Reflection on King Lear and King Dritharashtra Vandana Ravi MA

9ROXPH,,,,VVXH,0DUFK,661 When Blind Love for Kin Precedes Bounden Duty to Kingdom- A Reflection on King Lear and King Dritharashtra Vandana Ravi MA. B.Ed. (English) GC: 3rd Block Sree Vigneswara Apartments, Ayyappa Nagar, Poonkunnam Thrissur-680002, Kerala India Abstract An individual from his birth till death is destined to play many roles and thereby fulfill his/her expected duties. While doing so one should not compromise one’s duty in favour of another benefit especially when it is concerned with both personal and professional life affecting the lives of many. If done otherwise, the consequences would be disastrous as seen through the lives of Lear of Shakespeare’s King Lear and Dritharashtra of the Mahabharata. Both of them were Kings but at the same time also fathers whose love for their children overpowered their duty to their country and thereby their sense of taking right decisions as Kings. Dritharashtra’s blind love towards his sons especially Duryodhana made him overlook all their misdeeds leading to their death. On the other hand, Lear’s blind faith in his two greedy elder daughters’ (Goneril and Regan) proclamation of love much against the honest love of youngest daughter (Cordelia) leads to his destruction. Further, blind love for their children by the respective kings leads towards causing dereliction of duty to their countries. King Lear and King Dritharashtra, failing to keep equilibrium between their personal and professional duties, incurred the greatest loss of their life by losing their children. In short, life of King Lear and King Dritharashtra stand as a pointer to the world to show that, the consequences, when love for kin takes precedence over one’s duty towards the country, will always be detrimental. -

Bhagavad Gita Free

öËÅ Ç⁄∞¿Ë⁄“®¤ Ñ∆ || ¥˘®Ωæ Ã˘¤-í‹¡ºÎ ≤Ÿ¨ºÎ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿Ÿº® æË⁄í≤Ÿ | é∆ƒºÎ ¿Ÿú-æËíŸæ “ Ÿé¿Å || “§-⁄∆YŸºÎ ⁄“ º´—æ‰≥Æ˙-íË¿’-ÇŸYŸÅ ⁄∆úŸ≤™‰ | —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿ŸºÅ Ǩ∆Ÿ æËí¤ úŸ≤¤™‰ ™ ÇŸ¿Ëß‹ºÎ ÑôöËÅ Ç⁄∞¿Ë⁄“®¤ Ñ∆ || ¥˘®Ωæ Ã˘¤-í‹¡ºÎ ≤Ÿ¨ºÎ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿Ÿº‰® æË⁄í≤Ÿ | éÂ∆ƒºÎ ¿Ÿú ºŸ¿ŸºÅ é‚¥Ÿé¿Å || “§-⁄∆YŸºÎ ⁄“ º´—æ‰≥Æ˙-íË¿’-ÇŸYŸÅ ⁄∆úŸ≤™‰ | —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿ŸºÅ Ǩ∆Ÿ æËí¤ ¿Ÿú-æËíºÎ ÇŸ¿Ëß‹ºÎ ÑôöËÅ Ç⁄∞¿Ë⁄“®¤ Ñ∆ || ¥˘®Ωæ Ã˘¤-í‹¡ºÎ ≤Ÿ¨ºÎ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿Ÿº‰® æË⁄í≤Ÿ 韺Π∞%‰ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿ŸºÅ é‚¥Ÿé¿Å || “§-⁄∆YŸºÎ ⁄“ º´—æ‰≥Æ˙-íË¿’-ÇŸYŸÅ ⁄∆úŸ≤™‰ | —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿Ÿº ∫Ÿú™‰ ¥˘Ë≤Ù™-¿Ÿú-æËíºÎ ÇŸ¿Ëß‹ºÎ ÑôöËÅ Ç⁄∞¿Ë⁄“®¤ Ñ∆ || ¥˘®Ωæ Ã˘¤-í‹¡ºÎ ≤Ÿ¨ºÎ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿Ÿ §-¥˘Æ¤⁄¥éŸºÎ ∞%‰ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿ŸºÅ é‚¥Ÿé¿Å || “§-⁄∆YŸºÎ ⁄“ º´—æ‰≥Æ˙-íË¿’-ÇŸYŸÅ ⁄∆úŸ≤™‰ | -⁄∆YŸ | ⁄∆∫˘Ÿú™‰ ¥˘Ë≤Ù™-¿Ÿú-æËíºÎ ÇŸ¿ËßThe‹ºÎ ÑôöËÅ Ç⁄∞¿Ë⁄“®¤ Ñ∆ || ¥˘®Ωæ Ã˘¤-í‹¡ºÎ ≤Ÿ¨ ÇúŸ≤™ŸºÎ | “§-¥˘Æ¤⁄¥éŸºÎ ∞%Bhagavad‰ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿ŸºÅ é‚¥Ÿé¿Å Gita || “§-⁄∆YŸºÎ ⁄“ º´—æ‰≥Æ˙-íË¿’-ÇŸYŸ {Ÿ “§-æËí-⁄∆YŸ | ⁄∆∫˘Ÿú™‰ ¥˘Ë≤Ù™-¿Ÿú-æËíºÎ ÇŸ¿Ëß‹ºÎ ÑôöËÅ Ç⁄∞¿Ë⁄“®¤ Ñ∆ || ¥˘®Ωæ Ã˘¤ æËíºÎ ÇúŸ≤™ŸºÎ | “§-¥˘Æ¤⁄¥éŸºÎ ∞%‰ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿ŸºÅ é‚¥Ÿé¿Å || “§-⁄∆YŸºÎ ⁄“ º´—æ‰≥Æ˙-íË¿’ ≤ Ü¥⁄Æ{Ÿ “§-æËí-⁄∆YŸ | ⁄∆∫˘Ÿú™‰ ¥˘Ë≤Ù™-¿Ÿú-æËíºÎ ÇŸ¿Ëß‹ºÎ ÑôöËÅ Ç⁄∞¿Ë⁄“®¤ Ñ∆ || ¥˘ ≥™‰ ¿Ÿú-æËíºÎ ÇúŸ≤™ŸºÎ | “§-¥The˘Æ¤⁄¥éŸº OriginalÎ ∞%‰ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿ŸºÅSanskrit é‚¥Ÿé¿Å || “§-⁄∆YŸºÎ ⁄“ º´—æ‰ —ºÊ æ‰≤ Ü¥⁄Æ{Ÿ “§-æËí-⁄∆YŸ | ⁄∆∫˘Ÿú™‰ ¥˘Ë≤Ù™-¿Ÿú-æËíºÎ ÇŸ¿Ëß‹ºÎ ÑôöËÅ Ç⁄∞¿Ë⁄“®¤ Ñ “‹-º™-±∆Ÿ≥™‰ ¿Ÿú-æËíºÎ ÇúŸ≤™ŸºÎ | “§-¥˘Æ¤⁄¥éŸºand Î ∞%‰ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿ŸºÅ é‚¥Ÿé¿Å || “§-⁄∆YŸº Å Ç—™‹ ™—ºÊ æ‰≤ Ü¥⁄Æ{Ÿ “§-æËí-⁄∆YŸ | ⁄∆∫˘Ÿú™‰ ¥˘Ë≤Ù™-¿Ÿú-æËíºÎ ÇŸ¿Ëß‹ºÎ ÑôöËÅ Ç⁄∞¿ Ÿ ∏“‹-º™-±∆Ÿ≥™‰ ¿Ÿú-æËíºÎ ÇúŸ≤™ŸºÎ | “§-¥˘Æ¤⁄¥éŸºÎ ∞%‰ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿ŸºÅ é‚¥Ÿé¿Å || “§- An English Translation ≤Ÿ¨Ÿæ -

The Bhagavad Gita Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE BHAGAVAD GITA PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Laurie L. Patton, Simon Brodbeck | 288 pages | 28 Oct 2008 | Penguin Books Ltd | 9780140447903 | English | London, United Kingdom The Bhagavad Gita PDF Book Teaches the Practice of Yog The Bhagavad Gita is not content with providing a lofty philosophical understanding; it also describes clear-cut techniques for implementing its spiritual precepts for everyday life. His fear and hesitance become impediments to the proper balancing of the universal dharmic order. The Gita is the conversation between Krishna and Arjuna leading up to the battle. To follow the path advocated by the Bhagavad Gita would be their salvation, for it is a book of universal Self-realization, introducing man to his true Self, the soul—showing him how he has evolved from Spirit, how he may fulfill on earth his righteous duties, and how he may return to God. He says there is no true death of the soul -- simply a sloughing of the body at the end of each round of birth and death. The Wise who fully realize this engage in my devotional service and worship me with all their hearts. He masterly quotes from all the Vedic scriptures and many other sacred texts, opening up a panoramic view to help us see through the window of the Bhagavad Gita, the whole Absolute Truth. In the context of the Bhagavad-Gita it is bad karma not to respect the laws of God and the universe. The main ancient sources of information with regard to these Hindu beliefs and practises are the two great epics, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. -

Transition Into Kaliyuga: Tossups on Kurukshetra

Transition Into Kaliyuga: Tossups On Kurukshetra 1. On the fifteenth day of the Kurukshetra War, Krishna came up with a plan to kill this character. The previous night, this character retracted his Brahmastra [Bruh-mah-struh] when he was reprimanded for using a divine weapon on ordinary soldiers. After Bharadwaja ejaculated into a vessel when he saw a bathing Apsara, this character was born from the preserved semen. Because he promised that Arjuna would be the greatest archer in the world, this character demanded that (*) Ekalavya give him his right thumb. This character lays down his arms when Yudhishtira [Yoo-dhish-ti-ruh] lied to him that his son is dead, when in fact it was an elephant named Ashwatthama that was dead.. For 10 points, name this character who taught the Pandavas and Kauravas military arts. ANSWER: Dronacharya 2. On the second day of the Kurukshetra war, this character rescues Dhristadyumna [Dhrish-ta-dyoom-nuh] from Drona. After that, the forces of Kalinga attack this character, and they are almost all killed by this character, before Bhishma [Bhee-shmuh] rallies them. This character assumes the identity Vallabha when working as a cook in the Matsya kingdom during his 13th year of exile. During that year, this character ground the general (*) Kichaka’s body into a ball of flesh as revenge for him assaulting Draupadi. When they were kids, Arjuna was inspired to practice archery at night after seeing his brother, this character, eating in the dark. For 10 points, name the second-oldest Pandava. ANSWER: Bhima [Accept Vallabha before mention] 3. -

Rajaji-Mahabharata.Pdf

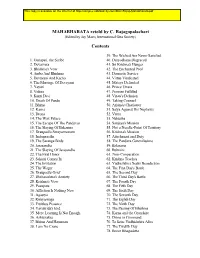

MAHABHARATA retold by C. Rajagopalachari (Edited by Jay Mazo, International Gita Society) Contents 39. The Wicked Are Never Satisfied 1. Ganapati, the Scribe 40. Duryodhana Disgraced 2. Devavrata 41. Sri Krishna's Hunger 3. Bhishma's Vow 42. The Enchanted Pool 4. Amba And Bhishma 43. Domestic Service 5. Devayani And Kacha 44. Virtue Vindicated 6. The Marriage Of Devayani 45. Matsya Defended 7. Yayati 46. Prince Uttara 8. Vidura 47. Promise Fulfilled 9. Kunti Devi 48. Virata's Delusion 10. Death Of Pandu 49. Taking Counsel 11. Bhima 50. Arjuna's Charioteer 12. Karna 51. Salya Against His Nephews 13. Drona 52. Vritra 14. The Wax Palace 53. Nahusha 15. The Escape Of The Pandavas 54. Sanjaya's Mission 16. The Slaying Of Bakasura 55. Not a Needle-Point Of Territory 17. Draupadi's Swayamvaram 56. Krishna's Mission 18. Indraprastha 57. Attachment and Duty 19. The Saranga Birds 58. The Pandava Generalissimo 20. Jarasandha 59. Balarama 21. The Slaying Of Jarasandha 60. Rukmini 22. The First Honor 61. Non-Cooperation 23. Sakuni Comes In 62. Krishna Teaches 24. The Invitation 63. Yudhishthira Seeks Benediction 25. The Wager 64. The First Day's Battle 26. Draupadi's Grief 65. The Second Day 27. Dhritarashtra's Anxiety 66. The Third Day's Battle 28. Krishna's Vow 67. The Fourth Day 29. Pasupata 68. The Fifth Day 30. Affliction Is Nothing New 69. The Sixth Day 31. Agastya 70. The Seventh Day 32. Rishyasringa 71. The Eighth Day 33. Fruitless Penance 72. The Ninth Day 34. Yavakrida's End 73. -

The Panchala Maha Utsav a Tribute to the Rich Cultural Heritage of Auspicious Panchala Desha and It’S Brave Princess Draupadi

Commemorting 10years with The Panchala Maha Utsav A Tribute to the rich Cultural Heritage of auspicious Panchala Desha and It’s brave Princess Draupadi. The First of its kind Historic Celebration We Enter The Past, To Create Opportunities For The Future A Report of Proceedings Of programs from 15th -19th Dec 2013 At Dilli Haat and India International Center 2 1 Objective Panchala region is a rich repository of tangible & intangible heritage & culture and has a legacy of rich history and literature, Kampilya being a great centre for Vedic leanings. Tangible heritage is being preserved by Archaeological Survey of India (Kampilya , Ahichchetra, Sankia etc being Nationally Protected Sites). However, negligible or very little attention has been given to the intangible arts & traditions related to the Panchala history. Intangible heritage is a part of the living traditions and form a very important component of our collective cultures and traditions, as well as History. As Draupadi Trust completed 10 years on 15th Dec 2013, we celebrated our progressive woman Draupadi, and the A Master Piece titled Parvati excavated at Panchala Desha (Ahichhetra Region) during the 1940 excavation and now a prestigious display at National Museum, Rich Cultural Heritage of her historic New Delhi. Panchala Desha. We organised the “Panchaala Maha Utsav” with special Unique Features: (a) Half Moon indicating ‘Chandravanshi’ focus on the Vedic city i.e. Draupadi’s lineage from King Drupad, (b) Third Eye of Shiva, (c) Exquisite Kampilya. The main highlights of this Hairstyle (showing Draupadi’s love for her hair). MahaUtsav was the showcasing of the Culture, Crafts and other Tangible and Intangible Heritage of this rich land, which is on the banks of Ganga, this reverend land of Draupadi’s birth, land of Sage Kapil Muni, of Ayurvedic Gospel Charac Saminhita, of Buddha & Jain Tirthankaras, the land visited by Hiuen Tsang & Alexander Cunningham, and much more. -

Part 1: the Beginning of Mahabharat

Mahabharat Story Credits: Internet sources, Amar Chitra Katha Part 1: The Beginning of Mahabharat The story of Mahabharata starts with King Dushyant, a powerful ruler of ancient India. Dushyanta married Shakuntala, the foster-daughter of sage Kanva. Shakuntala was born to Menaka, a nymph of Indra's court, from sage Vishwamitra, who secretly fell in love with her. Shakuntala gave birth to a worthy son Bharata, who grew up to be fearless and strong. He ruled for many years and was the founder of the Kuru dynasty. Unfortunately, things did not go well after the death of Bharata and his large empire was reduced to a kingdom of medium size with its capital Hastinapur. Mahabharata means the story of the descendents of Bharata. The regular saga of the epic of the Mahabharata, however, starts with king Shantanu. Shantanu lived in Hastinapur and was known for his valor and wisdom. One day he went out hunting to a nearby forest. Reaching the bank of the river Ganges (Ganga), he was startled to see an indescribably charming damsel appearing out of the water and then walking on its surface. Her grace and divine beauty struck Shantanu at the very first sight and he was completely spellbound. When the king inquired who she was, the maiden curtly asked, "Why are you asking me that?" King Shantanu admitted "Having been captivated by your loveliness, I, Shantanu, king of Hastinapur, have decided to marry you." "I can accept your proposal provided that you are ready to abide by my two conditions" argued the maiden. "What are they?" anxiously asked the king.