An Historical Analysis of Awankaru Sounds with a New'perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mutton Or Chicken Akhni

MUTTON OR CHICKEN AKHNI MUTTON OR CHICKEN AKHNI In a pot braise a large onion with oil (if using mutton) if chicken little oil n ghee till pale pink. Add in 1 teaspoon whole jeera seeds 4 whole black peppercorns 4 whole elachi pods 3 pieces cinnamon sticks 4 whole cloves 3 sliced green chillies Braise till golden brown. Then add in your meat or chicken. Add: 1 tablespoon of ginger and garlic paste 1 ½ teaspoon salt ±1 ½ teaspoon turmeric 1 teaspoon of red chilies paste STIR WELL Braise for a few minutes. Add some water and let cook till meat is tender. When meat is tender and water is almost dry add the other masalas: ± 2 tablespoons chili powder 2 teaspoons dhana /jeero powder 1 teaspoon crushed chillie powder some peas Braise nicely for few minutes then add in 1 grated tomato. Cook a few minutes. add 2 tbsp plain yogurt Add 6 cups boiling water and add in potatoes about 5 cut in pieces. Let boil for a few min so potatoes start getting soft. Lower heat a bit. Add 3 cups pre soaked basmati rice and add to pot. Add some salt for taste. Add in some chopped dhania and mint and about half teaspoon garam masala powder. Let boil for a few minutes till rice starts cooking. Stir also so well so that rice doesn’t stick to the bottom. When rice is boiling nicely and water is almost drying but there must be some water then put in oven and steam for about 30 to 40 minutes at 180°C. -

Restaurant Menu

Authentic Indian Cuisine STARTERS - MIXED STARTERS - SEAFOOD Mixed Kebab ......................................... £4.95 Prawn Cocktail ..................................... £3.95 Vegetable Platter (for two) ........................ £7.95 Prawn Puree .......................................... £4.95 Tikka Platter (for two) ............................... £8.95 Deep fried unleavened bread with prawn stuffing Sword Fish Tikka ................................... £5.95 STARTERS - VEGETABLE Stuffed Prawn Pepper ........................... £5.95 Onion Bhaji Deep fried spiced onion cutlets ......... £3.50 King Prawn Puree .................................. £5.95 Vegetable Samosa Deep fried pasties ........... £3.50 Deep fried unleavened bread with king prawn stuffing Aloo Chat Pieces of potato cooked in sour sauce ..... £3.50 King Prawn Garlic ................................. £5.95 Chilli Mushrooms .................................. £3.50 King prawn in garlic and butter Garlic Mushrooms ................................ £3.50 King Prawn Butterfly ............................. £5.95 Paneer Tikka ......................................... £3.75 King Prawns Shashlick BAZZAR special........ £5.95 Indian cheese marinated with spices and herbs Chana Paneer ........................................ £4.50 TANDOORI SPECIALITIES Channa puree ........................................ £4.50 These dishes are marinated with spices and then grilled in a special tandoor and served with salad Paneer Shashlick .................................. £4.50 Indian cheese -

THE PHONOLOGY of the VERBAL PHRASE in HINDKO Submitted By

THE PHONOLOGY OF THE VERBAL PHRASE IN HINDKO submitted by ELAHI BAKHSH AKHTAR AWAN FOR THE AWARD OF A DEGREE OF Ph.D. at the UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 1974 ProQuest Number: 10672820 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10672820 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 acknowledgment I wish to express my profound sense of gratitude and indebtedness to my supervisor Dr. R.K. Sprigg. But for his advice, suggestions, constructive criticism and above all unfailing kind ness at all times this thesis could not have been completed. In addition, I must thank my wife Riaz Begum for her help and encouragement during the many months of preparation. CONTENTS Introduction i Chapter I Value of symbols used in this thesis 1 1 .00 Introductory 1 1.10 I.P.A. Symbols 1 1.11 Other symbols 2 Chapter II The Verbal Phrase and the Verbal Word 6 2.00 Introductory 6 2.01 The Sentence 6 2.02 The Phrase 6 2.10 The Verbal Phra.se 7 2.11 Delimiting the Verbal Phrase 7 2.12 Place of the Verbal Phrase 7 2.121 -

Pauline and Other Studies

PAULINE AND OTHER STUDIES IN EARLY CHRISTIAN HISTORY BY W. M. RAM SAY, HoN. D.C.L., ETC. PROF~~SOR OF HUMANITY IN THE UNIVERSITY OF ABERDEEN HODDER AND STOUGHTON LONDON MCMVI VI THE PERMANENCE OF RELIGION AT HOLY PLACES IN WESTERN ASIA II Tomb of a Christian Virgin of the Third Cent).lry (see p. 298). VI THE PERMANENCE OF RELIGION AT HOLY PLACES IN WESTERN ASIA IN the preceding article in this volume, describing the origin of the Ephesian cult of the Mother of God, the permanent attachment of religious awe to special localities was briefly mentioned. In that cult we found a survival or revival of the old paganism of Ephesus, viz., the worship of the Virgin Mother of Artemis. The persistence of those ancient be liefs and rites at the chief centres of paganism exercised so pro found an influence on the history of Christianity in Asia Minor, that it is well to give a more detailed account of the facts, though even this account can only be a brief survey of a few examples selected almost by chance out of the in numerable cases which occur in all parts of the country. I shall take as the foundation of this article a paper read to the Oriental Congress held at London in autumn, 1902, and buried in the Transactions of the Congress, developing and improving the ideas expressed in that paper, and enlarging the number of examples. The strength of the old pagan beliefs did not escape the attention of the Apostle Paul; and his views on the subject affected his action as a missionary in the cities of Asia Minor; and can be traced in his letters. -

Jalalpur Irrigation Project: Land Acquisition and Resettlement Plan

Land Acquisition and Resettlement Plan (LARP) Project number: 46528–002 June 2019 PAK: Jalalpur Irrigation Project Prepared by the Irrigation Department, Government of the Punjab for the Asian Development Bank (ADB). This resettlement plan is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section of this website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. IRRIGATION DEPARTMENT, GOVERNMENT OF THE PUNJAB JALALPUR IRRIGATION PROJECT Land Acquisition and Resettlement Plan (LARP) for JIP/WKS/ICB-P2 (RD 52+000 to RD 225+500) (PART-1) May 2019 NATIONAL ENGINEERING SERVICES PAKISTAN (PVT) LIMITED NESPAK House, 1-C, Block-N, Model Town Extension, Lahore-54700, Pakistan PABX: 92 42 99090000 Fax: 92 42 99231940 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.nespak.com.pk Sub-Consultants INTEGRATED CONSULTING Technical Resource SERVICES (PVT) LIMITED766- Services (PVT) LIMITED13- G/4 JOHAR TOWN, LAHORE L Model Town Extension, Lahore PAKISTAN JIP-ADB PDA 6006: PAK Detailed Design Land Acquisition and Resettlement Plan of Jalalpur Irrigation Project ICB-P2 - RD 52+000 to RD 225+500 LAND ACQUISITION AND RESETTLEMENT PLAN TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No. LIST OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................................................... i LIST OF ANNEXURES ......................................................................................................................... -

Select Works of the Reverend and Learned David Clarkson

PRIMITIVE EPISCOPACY STATED AND CLEARED FROM THE HOLY SCRIPTURES AND ANCIENT RECORDS. By the late Reverend and Learned David Clarkson, sometime Fellow of Clare Hall, in Cambridge. London : Printed for Nath. Ponder at the Peacock in the Poultry. 1688. THE STATIONER TO THE READER. Though a preface be a civility due to the following tract, the name of the author is reckoned much more significant than any preface. Those that knew the calmness of his disposition, and his sincere desire of contributing all that he could to the com- posure of those unhappy differences that have so long troubled the Christian church, will think this work very suitable to his design; and being so esteemed by divers judicious persons of his acquaintance, those in whose hands Ins papers are, have been pre- vailed with to send it abroad into the world with this assurance, that it is his whose name it bears. Nath. Ponder. — THE CONTENTS. CHAPTER I. The benefit of this undertaking—What appears of Scripture times—Not a tenth part Christians in any city in the apostles' times ; scarce a twentieth—Act. ii. 45, cleared from what is confessed by prelates— 1. The number of the converted in the greatest cities were but small—2. That in those times there were more than one bishop in one city; it is also proved from Philip, i. 1 — Philippi no metropolis—Objection from Act. xvi. 12, removed— Act. xx. 17, 18, vindi- cated—Acknowledged that one altar was sufficient in those times. CHAPTER II. Bishops in villages, viz. Hydrax, Olbium, Zygris, &c.— Fuller's testimony in this matter—Instances of this kind in Cyprus, Armenia, Pontus, Lycaonia, &c.—An account of the bigness of the places mentioned, Act. -

Water Supply & Sanitation

WATER SUPPLY & SANITATION VISION Provision of adequate, safe drinking water and sanitation facilities to the entire rural and urban communities of Punjab through equitable, efficient and sustainable services. WATER & SANITATION POLICY Drinking Water Policy: Safe drinking water is accessible at premises, available when needed and free from contamination on sustainable basis to whole population of Punjab in addition to acquiring and adopting improved knowledge about safe drinking water, sanitation and hygiene in their daily life. Sanitation Policy: Policy envisions developing a safely managed sanitation environment for all citizens of the province, contributing towards high quality life in Punjab. OBJECTIVES . To achieve Sustainable Development Goals and its targets ( Goal 6.1 & 6.2 of SDGs) . Improving standards of public health through provision of improved services backed by legal, regulatory and binding framework. Laying down a roadmap for mobilization of resources to ensure provision of drinking water & sanitation to all by targeted timelines, assigning a priority to unserved and under-served areas . Focusing on capacity building of local governments and promoting Public- Private Partnerships to improve the operation and maintenance of water supply & sanitation schemes . To raise living standard of communities by providing quality drinking water and improved sanitation services . To reduce the spread of water borne diseases 123 ECONOMIC IMPACT OF WATER AND SANITATION PROJECTS The need for improved water and sanitation infrastructure is fundamental to the wellbeing of all citizens and increased coverage of these essential services will significantly contribute to socio-economic development. A study conducted by World Bank (2012) for Pakistan has shown that impact of poor sanitation and hygiene has cost the economy PKR 344 billion (US$ 6.0 billion) annually in 2006, or the equivalent to 3.9% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP). -

Kapadokya Kaya Kiliseleri'nde Hz. Isa Mucizelerinin Ikonografisi

T.C. SAKARYA ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ KAPADOKYA KAYA KİLİSELERİ’NDE HZ. İSA MUCİZELERİNİN İKONOGRAFİSİ YÜKSEK LİSANS TEZİ Göksevi AYHAN ATAK Enstitü Anabilim Dalı: Sanat Tarihi Tez Danışmanı: Dr. Öğr. Üyesi Gülsen TEZCAN KAYA MAYIS – 2019 ÖNSÖZ Hz. İsa’nın gerçekleştirdiği mucizeler, Hıristiyanlık inancında ve İncillerde önemi bir yer tutmaktadır. Meryem’in mucizevî hamileliği ile birlikte başlayan ve İsa’nın kutsal varlığının en önemli kanıtı olan mucizelere, Hırsitiyan İkonografisi’nde sıklıkla yer verilmiştir. Kapadokya Bölgesi’nin zengin duvar resimleri her dönem ilgi çekmiş ve farklı çalışmalara konu olmuştur. Bölgede, Hz. İsa mucizelerini konu alan tasvirlerin ikonografisi, tezimizin konusunu oluşturmaktadır. Çalışmam süresince, sabrı ve güler yüzüyle yol gösteren değerli danışmanım Dr. Öğr. Üyesi Gülsen TEZCAN KAYA’ya teşekkür ederim. Yüksek lisans eğitimim sürecinde bilgi ve desteklerini esirgemeyen değerli hocalarım Dr. Öğr. Üyesi Tülin ÇORUHLU, Doç. Dr. Ela TAŞ, Prof. Dr. Hamza GÜNDOĞDU ve Arş. Gör. Rümeysa Işık YAYLA’ya teşekkür borçluyum. Çalışma sürecinde ulaşamadığım yayınların temin edilmesinde yardımcı olan arkadaşım Öğr. Gör. İlknur GÜLTEKİN’e, gerekli bilgi ve fotoğrafların sağlamasında yardımlarını esirgemeyen Nevşehir Müze Müdürüğü çalışanı Osman RÜZGAR’a, Göreme Açık Hava Müzesi çalışanları Savaş GÜVEN ve Erdal GÖKSU’ya teşekkürlerimi sunarım. Son olarak, eğitim hayatım süresinde maddi ve manevi desteklerini esirgemeyen sevgili eşim Erkan ATAK’a ve ailemin değerli fertlerine sonsuz teşekkürler… Göksevi -

Monit6feet NÒFICIAL

Anul CXLIT Nr. 29 t. 120 1I EXEMPLARUL Luni 31 Decenwrie 1945. MONIT6feetPARTEA NÒFICIAL LEG1, D ECRETE JURNALE ALE CONSILIULUI DE MINISTRI, DECIZIUNI MINISTERIALE, CONUINICATE, A NUNTURI JUDICIARE (DE INTERES GENERAL) Partea I sau a II-a Desbaterile LIAII ARONAMENTE INLEI parlamenl. PUBLICA Tit IN LE! Insertle 3 had l 1 sesi une IN TARA DECRETE SI JURNALE ALE CONSILIULUI DE MINISTRI Acordarea avantajclor legil pentru incurajarea industrloi Particulari SAO 3.000 la Industriasi si fabricanti 36.1103 Auter/fAti de Vat. triplet si comune ur- Won la meseriasi si mori tArAnesti 7.100 bane 4.500 SchimbAri de nume, incetAteniri I la.009 Comunicato pentru depunerea lurAmAntului de incetAtenire18.000 AutoritAti comunale rurale 2.4C0 AutorizAri pentru infiintari de birouri vamate 11.000 IN STRAINATATE CITATIILE: una land CurtIlor de Casatie, de Conturl, de Apo iTribunaleIor . 2.700 000 Judecatorillor 1 300 Uri exemplar din anul curent lei 120 part. I-a 1160 part. II-a 160 PUBLICATIILE PENTRU AMENAJAMENTE DE PADUR1: anli trecuti 240 240 PAduri dela 0 10ha 1.1C0 . 10,01 29 3.600 20,01 100 5.400 Abenamentul la partea 111-a (resbater le parlamentare) pentru seslunile 100,01 200 ordinate. rrelunglte Sall extraoffnare se socoteste 1.600 lei lunar (minimum 27.1l0 1 lunA). e 200,01 500pl r, amen 1003 4 -.000 Abenamentele sipublicatiile pentru autorititi si particular! se plAtese 51.001 anticipat. Ele vor fi insolite de o adresti din partea autoritatilor si de o peste moo cerero timbratti din partea particularilor. PUBLICATII DIVERSE Institutia nu garanteazA trarsportul Brevete de Inventiuni I.000 Peatru trlmlterea chltantelor sau a ziarului pentru cererl de lämnriri SchlmbAri de nume 5 400 petilionarli vor trimite in plus suma de 100 lei spese de birou si porto simpht Libera practIcA profeslonalA .1.500 a mosItulul 2 70,) Pierderi de acte, (minimum 1.0091e1). -

District JHELUM CRITERIA for RESULT of GRADE 8

Notes, Books, Past Papers, Test Series, Guess Papers & Many More Pakistan's Educational Network - SEDiNFO.NET - StudyNowPK.com - EduWorldPK.com 3/31/2020 Punjab Examination Commission Gazette 2020 - Grade 8 District JHELUM CRITERIA FOR RESULT OF GRADE 8 Criteria JHELUM Punjab Status Minimum 33% marks in all subjects 84.88% 87.33% PASS Pass + Minimum 33% marks in four subjects and 28 to 32 marks Pass + Pass with 86.57% 89.08% in one subject Grace Marks Pass + Pass with Pass + Pass with grace marks + Minimum 33% marks in four Grace Marks + 95.59% 96.66% subjects and 10 to 27 marks in one subject Promoted to Next Class Candidate scoring minimum 33% marks in all subjects will be considered "Pass" One star (*) on total marks indicates that the candidate has passed with grace marks. Two stars (**) on total marks indicate that the candidate is promoted to next class. WWW.SEDiNFO.NET osrs.punjab.gov.pk 1/161 Notes, Books, Past Papers, Test Series, Guess Papers & Many More Pakistan's Educational Network - SEDiNFO.NET - StudyNowPK.com - EduWorldPK.com Notes, Books, Past Papers, Test Series, Guess Papers & Many More Pakistan's Educational Network - SEDiNFO.NET - StudyNowPK.com - EduWorldPK.com 3/31/2020 Punjab Examination Commission Gazette 2020 - Grade 8 PUNJAB EXAMINATION COMMISSION, RESULT INFORMATION GRADE 8 EXAMINATION, 2020 DISTRICT: JHELUM Pass + Students Students Students Pass % with Pass + Gender Promoted Registered Appeared Pass 33% marks Promoted % Students Male 7073 6979 6192 88.72 6782 97.18 Public School Female 8027 7945 6456 81.26 -

BANGLADESH: COUNTRY REPORT to the FAO INTERNATIONAL TECHNICAL CONFERENCE on PLANT GENETIC RESOURCES (Leipzig 1996)

BANGLADESH: COUNTRY REPORT TO THE FAO INTERNATIONAL TECHNICAL CONFERENCE ON PLANT GENETIC RESOURCES (Leipzig 1996) Prepared by: M. Sujayef Ullah Chowdhury Dhaka, April 1995 BANGLADESH country report 2 Note by FAO This Country Report has been prepared by the national authorities in the context of the preparatory process for the FAO International Technical Conference on Plant Genetic Resources, Leipzig, Germany, 17-23 June 1996. The Report is being made available by FAO as requested by the International Technical Conference. However, the report is solely the responsibility of the national authorities. The information in this report has not been verified by FAO, and the opinions expressed do not necessarily represent the views or policy of FAO. The designations employed and the presentation of the material and maps in this document do not imply the expression of any option whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. BANGLADESH country report 3 Table of contents FOREWORD 5 PREFACE 7 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION TO BANGLADESH AND ITS AGRICULTURE 10 CHAPTER 2 INDIGENOUS PLANT GENETIC RESOURCES 19 2.1 FOREST GENETIC RESOURCES 19 2.2 MEDICINAL PLANTS 22 2.3 OTHER WILD SPECIES AND WILD RELATIVES OF CROP PLANTS 22 2.4 LANDRACES (“FARMERS’ VARIETIES”) AND OLD CULTIVARS 22 CHAPTER 3 NATIONAL CONSERVATION ACTIVITIES 29 3.1 IN SITU CONSERVATION ACTIVITIES 30 3.2 EX SITU COLLECTIONS -

NHC Menu February 20

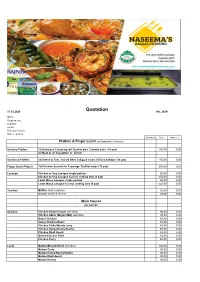

03 02 2020 Quotation No. 2020- Name Request no. Contact email Delivery Venue Date required Quantity Price Amount Platters & Finger Lunch (in Disposable Container) Savoury Platters 12xSamoosa 12xspring roll 12xmini pies 12xmeat balls (10 pax) 450,00 0,00 All Meat or all Veg option or all mix Sandwich Platters 3xCheese & Tom, 3xCold Beef, 3xEgg & salad, 3xTuna & Mayo (10 pax) 450,00 0,00 Finger lunch Platters 12xChicken drumsticks 12xwings 12xfillet strips (10 pax) 550,00 0,00 Lasange Chicken or Veg Lasagne single portion 60,00 0,00 Chicken or Veg Lasagne 1/2 rect chafing dish (9 pax) 450,00 0,00 Lamb Mince Lasagne single portion 65,00 0,00 Lamb Mince Lasagne 1/2 rect chafing dish (9 pax) 520,00 0,00 Tea time Muffins butter and jam 25,00 0,00 Scones butter & cheese 25,00 0,00 Main Course per person Chicken Chicken Biryani (layer) with dhay 80,00 0,00 Chicken Akhni (Biryani Mix) with dhay 70,00 0,00 Butter Chicken 65,00 0,00 Saucy Chicken Roast 65,00 0,00 Chicken Tikka Masala curry 65,00 0,00 Chicken Kaliya/Korma/Kariha 65,00 0,00 Chicken Dhall Gosht 65,00 0,00 Grilled Chicken Fillet 65,00 0,00 Chicken Curry 65,00 0,00 Lamb Mutton Biryani/Akhni with dhay 100,00 0,00 Mutton Curry 90,00 0,00 Mutton Kaliya/Korma/Kariha 90,00 0,00 Mutton Dhall Gosht 90,00 0,00 Mutton Keema 90,00 0,00 Beef Grilled Masala Steak 90,00 0,00 Grilled T-Bone 90,00 0,00 Saucy Pepper Steak 90,00 0,00 Salt & Pepper Grilled Steak 90,00 0,00 Gravy Steak 90,00 0,00 Gravy T-Bone 90,00 0,00 Beef Keema 90,00 0,00 Beef Korma/Kariha/Kaliya 90,00 0,00 Vegetable Vegetable Biryani/Akhni