The Macedonian “Have” and “Be” Perfects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Introduction, Phonological, Morphological, Syntactic to The

AN INTRODUCTION, PHONOLOGICAL, MORPHOLOGICAL, SYNTACTIC, TO THE GOTHIC OF ULFILAS. BY T. LE MARCHANT DOUSE. LONDON: TAYLOR AND FRANCIS, RED LION COURT, FLEET STREET. 1886, PRINTED BY TAYLOR AND FRANCIS, BED LION COURT, FLEET STREET. PREFACE. THIS book was originally designed to accompany an edition of Ulfilas for which I was collecting materials some eight or nine years ago, but which various con- siderations led me to lay aside. As, however, it had long seemed to me equally strange and deplorable that not a single work adapted to aid a student in acquiring a knowledge of Gothic was to be found in the English book-market, I pro- ceeded to give most of the time at my disposal to the " building up of this Introduction," on a somewhat larger scale than was at first intended, in the hope of being able to promote the study of a dialect which, apart from its native force and beauty, has special claims on the attention of more than one important class of students. By the student of linguistic science, indeed, these claims are at once admitted ; for the Gothic is one of the pillars on which rests the comparative grammar of the older both Indo-European languages in general, and also, pre-eminently, of the Teutonic cluster of dialects in particular. a But good knowledge of Gothic is scarcely less valuable to the student of the English language, at rate, of the Ancient or any English Anglo-Saxon ; upon the phonology of which, and indeed the whole grammar, the Gothic sheds a flood of light that is not to be got from any other source. -

The Truth About Greek Occupied Macedonia

TheTruth about Greek Occupied Macedonia By Hristo Andonovski & Risto Stefov (Translated from Macedonian to English and edited by Risto Stefov) The Truth about Greek Occupied Macedonia Published by: Risto Stefov Publications [email protected] Toronto, Canada All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system without written consent from the author, except for the inclusion of brief and documented quotations in a review. Copyright 2017 by Hristo Andonovski & Risto Stefov e-book edition January 7, 2017 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface................................................................................................6 CHAPTER ONE – Struggle for our own School and Church .......8 1. Macedonian texts written with Greek letters .................................9 2. Educators and renaissance men from Southern Macedonia.........15 3. Kukush – Flag bearer of the educational struggle........................21 4. The movement in Meglen Region................................................33 5. Cultural enlightenment movement in Western Macedonia..........38 6. Macedonian and Bulgarian interests collide ................................41 CHAPTER TWO - Armed National Resistance ..........................47 1. The Negush Uprising ...................................................................47 2. Temporary Macedonian government ...........................................49 -

The Origin and Spread of Locative Determiner Omission in the Balkan Linguistic Area

The Origin and Spread of Locative Determiner Omission in the Balkan Linguistic Area by Eric Heath Prendergast A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Line Mikkelsen, Chair Professor Lev Michael Professor Ronelle Alexander Spring 2017 The Origin and Spread of Locative Determiner Omission in the Balkan Linguistic Area Copyright 2017 by Eric Heath Prendergast 1 Abstract The Origin and Spread of Locative Determiner Omission in the Balkan Linguistic Area by Eric Heath Prendergast Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Berkeley Professor Line Mikkelsen, Chair This dissertation analyzes an unusual grammatical pattern that I call locative determiner omission, which is found in several languages belonging to the Slavic, Romance, and Albanian families, but which does not appear to have been directly inherited from any individual genetic ancestor of these languages. Locative determiner omission involves the omission of a definite article in the context of a locative prepositional phrase, and stands out as a feature of the Balkan linguistic area for which there are few, if any crosslinguistic parallels. This investigation of the origin and diachronic spread of locative determiner omission serves the particular goal of revealing how the social context of language contact could have resulted in a pattern of grammatical borrowing without lexical borrowing, yielding a present distribution in which locative determiner omission appears in several Balkan languages no longer in direct contact with one another. A detailed structural and historical analysis of locative determiner omission in Albanian, Romanian, Aromanian, and Macedonian is used as a basis for comparison with other Balkan languages. -

Greek Occupied Macedonia (1913-1989)

Greek occupied Macedonia (1913-1989) By Stoian Kiselinovski (Translated from Macedonian to English and edited by Risto Stefov) Greek occupied Macedonia (1913-1989) Published by: Risto Stefov Publications [email protected] Toronto, Canada All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system without written consent from the author, except for the inclusion of brief and documented quotations in a review. Copyright 2018 by Stoian Kiselinovski & Risto Stefov e-book edition ********** January 24, 2018 ********** 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE ..........................................................................................6 CHAPTER ONE - NATIONAL STRUCTURE OF THE POPULATION IN GREEK OCCUPIED MACEDONIA AT THE BEGINNING OF THE XX CENTURY (1900 - 1913).....................8 1. BULGARIAN STATISTICS ON THE NATIONAL STRUCTURE OF THE POPULATION IN GREEK OCCUPIED MACEDONIA ...............................................................................9 2. SERBIAN STATISTICS ON THE NATIONAL STRUCTURE OF THE POPULATION IN GREEK OCCUPIED MACEDONIA ......................................................................................................12 3. GREEK STATISTICS ON THE NATIONAL STRUCTURE OF THE POPULATION IN GREEK OCCUPIED MACEDONIA ......................................................................................................14 CHAPTER TWO - CHANGING THE ETHNIC COMPOSITION -

Romani Language Standardisation PUBLISHER: Kali Sara Association Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina

u A v th k d c ćh r Es g Rajko Đurić j p ROMANI c f LANGUAGE b z i STANDARDISATION e ćh m g Rajko Đurić Romani Language Standardisation PUBLISHER: Kali Sara Association Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina EDITORS: Sanela Bešić Dervo Sejdić Sandra Zlotrg TRA NSLATION: Context DESIGN: Jasmin Leventa PRINTING: Dobra knjiga d.o.o. CIRCULATION: 200 copies Association Kali Sara - Roma Information Center would like to thank all persons who contributed to the implementation of the project “Romani Language Standardisation for the Countries of Western Balkans”. We primarily thank our donors – UNICEF and Open Society Fund – who recognized the importance of this project and supported it, the consultants, working group participants – representatives of ministries, Romani language experts, representatives of Romani non-governmental organizations, and out key expert, professor Rajko Đurić without whom this document would not have been possible. Th is publication was funded by UNICEF BiH. Rajko Đurić Romani Language Standardisation KA LI SARA ASSOCIATION Sarajevo, 2012 FOREWORD BY DONORS UNICEF is committ ed to support and sustain quality education for every child in Bosnia and Herzegovina like everywhere in the world. We recognize the right of every child to speak his or her native language and to receive an education that respects the child’s own cultural identity and values. As stated in the Convention on the Rights of the Child – Children belonging to ethnic, religious or linguistic minorities have the right to enjoy their own culture and to use their own language (Article 30). A language is not only a communication tool, it is also a way to understand and categorize one’s reality, knowledge, social relationships and emotions. -

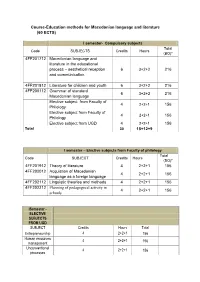

Course-Education Methods for Macedonian Language and Literature (60 ECTS)

Course-Education methods for Macedonian language and literature (60 ECTS) I semester- Compulsory subjects Total Code SUBJECTS Credits Hours (ВО)* 4FF201712 Macedonian language and litarature in the educational process – aesthetical reception 6 3+2+2 216 and communication 4FF201812 Litarature for children and youth 6 3+2+2 216 4FF200112 Grammar of standard 6 3+2+2 216 Macedonian language Elective subject from Faculty of 4 2+2+1 156 Philology Elective subject from Faculty of 4 2+2+1 156 Philology Elective subject from UGD 4 2+2+1 156 Total 30 15+12+9 I semester – Elective subjects from Faculty of philology Total Code SUBJECT Credits Hours (ВО)* 4FF201912 Theory of literature 4 2+2+1 156 4FF202012 Acquistion of Macedonian 4 2+2+1 156 language as a foreign language 4FF202112 Linguistic theories and methods 4 2+2+1 156 4FF202212 Planning of pedagogocal activity in 4 2+2+1 156 schools ISemester - ELECTIVE SUBJECTS FROM UGD SUBJECT Credits Hours Total Entrepreneurship 4 2+2+1 156 Human resources 4 2+2+1 156 management Unconventional 4 2+2+1 156 processes Plastic processing 4 2+2+1 156 technologies European Union – Institutions and 4 2+2+1 156 Law Political parties 4 2+2+1 156 Design and analysis of 4 2+2+1 156 experiments History and 4 2+2+1 156 Theory of Design Mechanical properties of 4 2+2+1 156 textiles Web Technologies for 4 2+2+1 156 Business Support Businessdata 4 2+2+1 156 communications E-learning 4 2+2+1 156 Finite Element 4 2+2+1 156 Method AppliedData 4 2+2+1 156 Analysis Business foreign language (English UGD202412 4 2+2+1 156 language)* -

C Cat Talo Ogu Ue

PACIF IC LINGUISTICS Catalogue February, 2013 Pacific Linguistics WWW Home Page: http://pacling.anu.edu.au/ Pacific Linguistics School of Culture, History and Language College of Asia and the Pacific THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY See last pagee for order form FOUNDING EDITOR: S.A. Wurm MANAGING EDITOR: Paul Sidwell [email protected] EDITORIAL BOARD: I Wayan Arka, Mark Donohue, Bethwyn Evan, Nicholas Evans, Gwendolyn Hyslop, David Nash, Bill Palmer, Andrew Pawley, Malcolm Ross, Paul Sidwell, Jane Simpson, and Darrell Tryon ADDRESS: Pacific Linguistics School of Culture, History and Language College of Asia and the Pacific The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200 Australia Phone: +61 (02 6125 2742 E-mail: [email protected] Home page: http://www.pacling.anu.edu.au// 1 2 Pacific Linguistics Pacific Linguistics Books Online http://www.pacling.anu.edu.au/ Austoasiatic Studies: PL E-8 Papers from ICAAL4: Mon-Khmer Studies Journal, Special Issue No. 2 Edited by Sophana Srichampa & Paul Sidwell This is the first of two volumes of papers from the forth International Conference on Austroasiatic Linguistics (ICAAL4), which was held at the Research Institute for Language and Culture of Asia, Salaya campus of Mahidol University (Thailand) 29-30 October 2009. Participants were invited to present talks related the meeting theme of ‘An Austroasiatic Family Reunion’, and some 70 papers were read over the two days of the meeting. Participants came from a wide range of Asian countries including Thailand, Malaysia, Vietnam, Laos, Myanmar, India, Bangladesh, Nepal, Singapore and China, as well as western nations. Published by: SIL International, Dallas, USA Mahidol University at Salaya, Thailand / Pacific Linguistics, Canberra, Australia ISBN 9780858836419 PL E-7 SEALS XIV Volume 2 Papers from the 14th annual meeting of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society 2004 Edited by Wilaiwan Khanittanan and Paul Sidwell The Fourteenth Annual Meeting of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society was held in Bangkok , Thailand , May 19-21, 2004. -

Language Distinctiveness*

RAI – data on language distinctiveness RAI data Language distinctiveness* Country profiles *This document provides data production information for the RAI-Rokkan dataset. Last edited on October 7, 2020 Compiled by Gary Marks with research assistance by Noah Dasanaike Citation: Liesbet Hooghe and Gary Marks (2016). Community, Scale and Regional Governance: A Postfunctionalist Theory of Governance, Vol. II. Oxford: OUP. Sarah Shair-Rosenfield, Arjan H. Schakel, Sara Niedzwiecki, Gary Marks, Liesbet Hooghe, Sandra Chapman-Osterkatz (2021). “Language difference and Regional Authority.” Regional and Federal Studies, Vol. 31. DOI: 10.1080/13597566.2020.1831476 Introduction ....................................................................................................................6 Albania ............................................................................................................................7 Argentina ...................................................................................................................... 10 Australia ....................................................................................................................... 12 Austria .......................................................................................................................... 14 Bahamas ....................................................................................................................... 16 Bangladesh .................................................................................................................. -

Introduction

Introduction Božidar Vidoeski (born 8 November 1920 in Zvečan, Poreče region, Repub- lic of Macedonia) was the father of Modern Macedonian dialectology. Not only did he publish numerous studies of individual dialects but also broader syntheses that superseded all previous attempts and that remain to this day the foundations of Slavic dialectology on Macedonian linguistic territory. The present collection contains translations of eight of Vidoeski’s most im- portant general Macedonian dialectological works, as well as his complete bibliography. It can thus serve as a basic textbook for any course that deals with Macedonian dialects but is also a fund of information and analysis for any scholar interested in the Macedonian language. Vidoeski was educated in both Yugoslavia and Macedonia. He received his BA in 1949 and was immediately appointed to an instructorship in what was then the Department of South Slavic Languages of the Philosophical Faculty of the University of Skopje. His BA thesis, on the dialect of his na- tive Poreče region, published in 1950, was the first BA thesis published by his Department. He received his doctorate in 1957 and was promoted to as- sistant professor in 1958. In 1964 he was promoted to associate professor and to full professor in 1967. He was elected to the Macedonian Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1969. From 1971–77 he directed the Seminar for Ma- cedonian language, literature, and culture, and in 1974 he initiated the Schol- arly Colloquium (Naučna diskusija) as part of the activities of the Seminar. He was chairman of the Macedonian Department at the University of Skopje for many years and served as the general editor of the journal Makedonski jazik, published by the Institute for Macedonian Language, from 1973 until his death. -

Chapter 22 Linguistic Affiliation

Chapter 22 Linguistic Affiliation In the preceding chapter i gave you a very quick survey of some of the more common ways in which languages are known to change. Now we are going to take a closer look at what is known about the processes of language change and how we can use this knowledge to reconstruct language history. Note my use of the word ‘reconstruct’ or ‘reconstruction’. Bear in mind that, when we talk about language history, to a great extent we are talking history that isn't clearly recorded anywhere. For instance, if you look at European culture nowadays you will find a great many different languages — Czech, Danish, Dutch, English, Finnish, French, German, Greek, Hungarian, Icelandic, Italian, Nor- wegian, Polish, Portuguese, Russian, Slovene, Spanish, Swedish, to mention only a few of the more important ones — most of which are nevertheless recognizably related to each other.1 Pushing back as far as we can in the historical records it becomes obvious that French, Italian, Portuguese, and Spanish are all descended from Latin, and we have plenty of records of Latin. Czech, Polish, Russian, and Slovene are clearly all related to an older language called Old Church Slavonic,2 for which we have records. Danish, Icelandic, Norwegian, and Swedish are all descended from a language usually referred to as Old Norse, for which we have records from about 800–1000 years ago, while Dutch, English, and German are all somehow or other related to what is usually called Old High German, for which we have some records, but the details of the relationship are not quite as obvious as one might like. -

Ideology in Grammar

Paris-Lodron-Universität Salzburg, April 10–12 2014 Ideology in Grammar Book of abstracts Gradient grammaticality and gradient acceptability in English as a Lingua Franca Piotr Choromański (Warsaw) The quite recent evolution of English to the official language of all mankind has created a unique linguistic situation in world history. This has engendered a broad spectrum of understandings and opinions about the place that the language has or should have in the world. English as a Global Language, English as an International Language and English as a Lingua Franca are some of the terms coined to reflect the wide variety of contexts contemporary English is used in. The notions of grammaticality and acceptability are at the heart of the debate about the shape and dynamic nature of English as a Lingua Franca. Grammatical correctness and acceptability are theoretical constructs deeply ingrained in the branch of science dedicated to the study of human language. Moreover, the abstract idea of grammaticality can only be discussed and elucidated with explicit reference to an existing formal representation of grammatical competence. English as a Lingua Franca is not a term denoting a type of English but a notion embodying how English as a Native Language, English as a Second Language and English as a Foreign Language are used today. More to the point, there are no speakers of English as a Lingua Franca in the world. There are only speakers of English as a Native Language, English as a Second Language and English as a Foreign Language. Simply put, English as a Lingua Franca is the English that native speakers and non-native users rely on in international and intercultural contexts. -

Context-Free Grammars for Macedonian Language

IJournals: International Journal of Software & Hardware Research in Engineering ISSN-2347-4890 Volume 5 Issue 2 February, 2017 Context-free Grammars for Macedonian Language Author: Kristina Bikoska1; Slavco Chungurski2; Emilija Kamceva3 FON University Skopje Macedonia E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] ABSTRACT analysis and generation. A commonly used mathematical system for modelling constituent Modern approaches to the language are one kind structure in Natural Language is Context-Free of provocation for research in different branches. Grammar (CFG) which was first defined for The main idea that connects all of them historically Natural Language in (Chomsky 1957) and was and theoretically is the term universal grammar, or independently discovered for the description of the Algol programming language by Backus (1959) formalization of natural languages, which learns and Naur (1960). In this paper, one fragment of about the main characteristics of the language. Macedonian language will be presented as context- Such formalization depends on the nature and free grammar. Context-Free grammars belong to structure of the language. Natural language has an the realm of formal language theory (cf. Hopcroft underlying structure usually referred to under the and Ullman 1974 for a detailed overview) where a heading of Syntax. The syntax of one language language (formal or natural) is viewed as a set of refers to the principles by which words are sentences. A sentence as a string of one or more words from the vocabulary of the language and a grouped together. This paper formally represents grammar as a finite, formal specification of the the grammar for one piece of Macedonian (possibly infinite) set of sentences composing the language as a context - free grammar (CFG).