John Ray's Natural History Travels

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 2 Fundamental Questions: Linneaus and Kirchner

2/1/2011 The 2 fundamental questions: y Has evolution taken pp,lace, and if so, what is the Section 4 evidence? Professor Donald McFarlane y If evolution has taken place, what is the mechanism by which it works? Lecture 2 Evolutionary Ideas Evidence for evolution before Darwin Golden Age of Exploration y Magellan’s voyage –1519 y John Ray –University of y Antonius von Leeuwenhoek ‐ microbes –1683 Cambridge (England) y “Catalog of Cambridge Plants” – 1660 –lists 626 species y 1686 –John Ray listing thousands of plant species! y In 1678, Francis Willoughby publishes “Ornithology” Linneaus and Kirchner Athenasius Kircher ~ 1675 –Noah’s ark Carl Linneaus – Sistema Naturae ‐ 1735 Ark too small!! Uses a ‘phenetic” classification – implies a phylogenetic relationship! 300 x 50 x 30 cubits ~ 135 x 20 x 13 m 1 2/1/2011 y Georges Cuvier 1769‐ 1832 y “Fixity of Species” Evidence for Evolution –prior to 1830 • Enormous diversity of life –WHY ??? JBS Haldane " The Creator, if He exists, has "an inordinate fondness for beetles" ". Evidence for Evolution –prior to 1830 Evidence for Evolution –prior to 1830 y The discovery of variation. y Comparative Anatomy. Pentadactyl limbs Evidence for Evolution –prior to Evidence for Evolution –prior to 1830 1830 y Fossils – homologies with living species y Vestigal structures Pentadactyl limbs !! 2 2/1/2011 Evidence for Evolution –prior to 1830 Evidence for Evolution –prior to 1830 y Invariance of the fossil sequence y Plant and animal breeding JBS Haldane: “I will give up my belief in evolution if someone finds a fossil rabbit in the Precambrian.” Charles Darwin Jean Baptiste Lamark y 1744‐1829 y 1809 –1882 y Organisms have the ability to adapt to their y Voyage of Beagle 1831 ‐ 1836 environments over the course of their lives. -

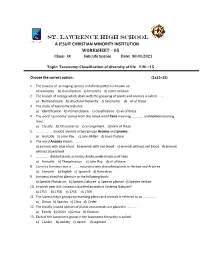

ST. LAWRENCE HIGH SCHOOL a JESUIT CHRISTIAN MINORITY INSTITUTION WORKSHEET – 05 Class: IX Sub: Life Science Date: 30.01.2021

ST. LAWRENCE HIGH SCHOOL A JESUIT CHRISTIAN MINORITY INSTITUTION WORKSHEET – 05 Class: IX Sub: Life Science Date: 30.01.2021 Topic: Taxonomy-Classification of diversity of life F.M. : 15 Choose the correct option: (1x15=15) 1. The process of arranging species in definite pattern is known as: a) taxonomy b) classification c) hierarchy d) nomenclature 2. The branch of biology which deals with the grouping of plants and animals is called …….. a) Nomenclature b) structural hierarchy c) taxonomy d) all of these 3. The study of taxonomy includes: a) Identification b) nomenclature c) classification d) all of these 4. The word ‘taxonomy’ comes from the Greek word Taxis meaning ………….. and nomos meaning laws: a) Classify b) Characterize c) arrangement d)none of these 5. ……………….. divided animals in two groups Anaima and Enaima . a) Aristotle b) John Ray c) John Miller d) Louis Pasteur 6. The word Anaima means …...... a) animals with blue blood b) animals with red blood c) animals without red blood d) animals without blue blood 7. ……………. divided plants as herbs,shrubs,undershrubs and trees. a) Aristotle b) Theophrastus c) John Ray d) all of these 8. Carrolus Linnaeus was a ……… naturalist who classisfied plants in Herbae and Arborea. a) Swedish b) English c) Spainish d) Australian 9. Linnaeus classified plants in in the following book: a) Species Plantarum b) Species Naturae c) Species plantae d) Species herbae 10. In which year did Linnaeus classified animals in Systema Naturae? a) 1753 b) 1758 c) 1756 d) 1769 11. The lowest major group representing plants and animals is referred to as …………… a) Genus b) Species c) Class d) Order 12. -

Ministers of ‘The Black Art’: the Engagement of British Clergy with Photography, 1839-1914

Ministers of ‘the Black Art’: the engagement of British clergy with photography, 1839-1914 Submitted by James Downs to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in March 2018 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signature: ………………………………………………………….. Abstract 1 Ministers of ‘the Black Art’: the engagement of British clergy with photography, 1839- 1914 This thesis examines the work of ordained clergymen, of all denominations, who were active photographers between 1839 and the beginning of World War One: its primary aim is to investigate the extent to which a relationship existed between the religious culture of the individual clergyman and the nature of his photographic activities. Ministers of ‘the Black Art’ makes a significant intervention in the study of the history of photography by addressing a major weakness in existing work. Taking an interdisciplinary approach, the research draws on a wide range of primary and secondary sources such as printed books, sermons, religious pamphlets, parish and missionary newsletters, manuscript diaries, correspondence, notebooks, biographies and works of church history, as well as visual materials including original glass plate negatives, paper prints and lantern slides held in archival collections, postcards, camera catalogues, photographic ephemera and photographically-illustrated books. -

The Charles Knight-Joseph Hooker Correspondence

A man tenax propositi: transcriptions of letters from Charles Knight to William Jackson Hooker and Joseph Dalton Hooker between 1852 and 1883 David J. Galloway Hon. Research Associate Landcare Research, and Te Papa Tongarewa [email protected] Geoscience Society of New Zealand miscellaneous publication 133J December 2013 Published by the Geoscience Society of New Zealand Inc, 2013 Information on the Society and its publications is given at www.gsnz.org.nz © Copyright David J. Galloway, 2013 Geoscience Society of New Zealand miscellaneous publication 133J ISBN 978-1-877480-36-2 ISSN 2230-4495 (Online) ISSN 2230-4487 (Print) This document is available as a PDF file that can be downloaded from the Geoscience Society website at: http://www.gsnz.org.nz/information/misc-series-i-49.html Bibliographic Reference Galloway D.J. 2013: A man tenax propositi: transcriptions of letters from Charles Knight to William Jackson Hooker and Joseph Dalton Hooker between 1852 and 1883 Geoscience Society of New Zealand miscellaneous publication 133J. 88 pages. A man tenax propositi: transcriptions of letters from Charles Knight to William Jackson Hooker and Joseph Dalton Hooker between 1852 and 1883 Contents Introduction 3 Charles Knight correspondence at Kew 5 Acknowledgements 6 Summaries of the letters 7 Transcriptions of the letters from Charles Knight 15 Footnotes 70 References 77 Figure 1: Dr Charles Knight FLS, FRCS 2 Figure 2: Group photograph including Charles Knight 2 Figure 3: Page of letter from Knight to Hooker 14 Table 1: Comparative chronology of Charles Knight, W.J. Hooker and J.D. Hooker 86 1 Figure 1: Dr Charles Knight FLS, FRCS Alexander Turnbull Library,Wellington, New Zealand ¼-015414 Figure 2: Group taken in Walter Mantell‟s garden about 1865 showing Charles Knight (left), John Buchanan and James Hector (right) and Walter Mantell and his young son, Walter Godfrey Mantell (seated on grass). -

History of Taxonomy

History of Taxonomy The history of taxonomy dates back to the origin of human language. Western scientific taxonomy started in Greek some hundred years BC and are here divided into prelinnaean and postlinnaean. The most important works are cited and the progress of taxonomy (with the focus on botanical taxonomy) are described up to the era of the Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus, who founded modern taxonomy. The development after Linnaeus is characterized by a taxonomy that increasingly have come to reflect the paradigm of evolution. The used characters have extended from morphological to molecular. Nomenclatural rules have developed strongly during the 19th and 20th century, and during the last decade traditional nomenclature has been challenged by advocates of the Phylocode. Mariette Manktelow Dept of Systematic Biology Evolutionary Biology Centre Uppsala University Norbyv. 18D SE-752 36 Uppsala E-mail: [email protected] 1. Pre-Linnaean taxonomy 1.1. Earliest taxonomy Taxonomy is as old as the language skill of mankind. It has always been essential to know the names of edible as well as poisonous plants in order to communicate acquired experiences to other members of the family and the tribe. Since my profession is that of a systematic botanist, I will focus my lecture on botanical taxonomy. A taxonomist should be aware of that apart from scientific taxonomy there is and has always been folk taxonomy, which is of great importance in, for example, ethnobiological studies. When we speak about ancient taxonomy we usually mean the history in the Western world, starting with Romans and Greek. However, the earliest traces are not from the West, but from the East. -

Middleton and John Ray Jo Walker from Middleton Hall on the Story Behind an Historic and Rare Rose

Middleton and John Ray Jo Walker from Middleton Hall on the story behind an historic and rare rose Middleton Hall is a Grade ‘Historia Piscium’ were II* listed manor with a published after his death by John Ray. John Ray tutored museum housed in Francis’ children whilst he buildings spanning 750 stayed at Middleton Hall and years of architectural remained at the Hall for a Rose “John Ray” is believed to survive styles. The surrounding number of years after Francis’ only in Middleton Hall’s walled garden estate covers 42 acres and death. It was at Middleton that he developed his original works includes a Site of Special on Natural History including his was gradually superseded by the Scientific Interest, a walled ‘History of Plants’. garden and shops. Now Linnean method which was first John Ray (1627-1705) applied to English botany in Dr J. restored the Hall is run by Philosopher and writer, cleric, Hill’s Flora Britannica 1760. a small independent traveller and taxonomist, Ray enjoyed the advantage of a charitable trust. Middleton deserves a wider reputation. His very long period of productive botanical works - ‘Historiae Hall has had a wide variety activity: in the thirty-four years Plantum’ and ‘Methodus of owners and tenants. that separated his Tables of Plantarum Nova’, were published Plants from his Methodus Two of our most famous 1682. Emendata et Aucta, he had time residents were the great Known as the father of English to revise and remodel his naturalists Francis Willughby natural history, John Ray’s system. (who spelt his name this way) system of plant classification and his tutor, friend and During his residence in became more popular than that collaborator John Ray. -

The Life and Times of a Curiosity-Monger

COMMENT BOOKS & ARTS Like Close, astronomer John MUSEUMS Dvorak hopscotches through eclipses in Mask of the Sun, but this is science his- tory rather than anecdote. The quotes he interweaves reveal the extraordinary The life and times of a pull the events have had on the human imagination. The writer Virginia Woolf, for instance, who had witnessed the 1927 curiosity-monger total solar eclipse in the north of England, wrote of it in her essay ‘The sun and the Henry Nicholls revels in a biography of Enlightenment fish’ the following year: “Show me the collector and Royal Society president Hans Sloane. eclipse, we say to the eye; let us see that strange spectacle again.” It’s a rich chronicle. Dvorak notes, for hat do bloodletting, slavery, instance, how in 1684 Increase Mather, journal editing and a silver penis the president of Harvard College in Cam- protector have in common? The bridge, Massachusetts, delayed the gradu- Weighteenth-century physician, collector and ation ceremony by ten days so that faculty president of the Royal Society Hans Sloane. PHOTOS.COM/GETTY members and students could reach Mar- In Collecting the World, historian James tha’s Vineyard off the state’s south coast Delbourgo charts Sloane’s rags-to-riches to see a total eclipse. (Mather, a Puritan transformation, from his birth in 1660 into minister, was less enlightened about the a family of domestic servants in the north Salem witch trials less than a decade later, of Ireland, to his death in 1753 as one of the refusing to condemn them.) We see how most influential figures in England. -

THE MAN of SCIENCE Steven Shapin

THE IMAGE OF THE MAN OF SCIENCE Steven Shapin The relations between the images of the man of science and the social and cultural realities of scientific roles are both consequential and contingent. Finding out “who the guys were” (to use Sir Lewis Namier’s phrase) does in- deed help to illuminate what kinds of guys they were thought to be, and, for that reason alone, any survey of images is bound to deal – to some extent at least – with what are usually called the realities of social roles.1 At the same time, it must be noted that such social roles are always very substantially con- stituted, sustained, and modified by what members of the culture think is, or should be, characteristic of those who occupy the roles, by precisely whom this is thought, and by what is done on the basis of such thoughts. In socio- logical terms of art, the very notion of a social role implicates a set of norms and typifications – ideals, prescriptions, expectations, and conventions thought properly, or actually, to belong to someone performing an activity of a certain kind. That is to say, images are part of social realities, and the two notions can be distinguished only as a matter of convention. Such conventional distinctions may be useful in certain circumstances. So- cial action – historical and contemporary – very often trades in juxtapositions between image and reality. One might hear it said, for example, that modern American lawyers do not really behave like the high-minded professionals 1 For introductions to pertinent prosopography, see, e.g., Robert M. -

The Apothecary As Man of Science

Iv THE APOTHECARY AS MAN OF SCIENCE INTRODUCTION The development and use of rational scientific methods was well established by the mid-seventeenth century. The collection of data and the systematic arrangement of ideas, the application of mathematics and sound reasoning, and, above all, the experi- mental testing of hypotheses, advocated by men of the calibre of Johan Kepler (1571-1630), Galileo Galilei (1564-1642), Francis Bacon (1561-1626), and Rene Descartes (1596-1650) were, by the time of the Commonwealth, accepted roads to the advancement of knowledge. A new intellectual outlook had evolved, as noted by John Aubrey (1626-97) in 1671, "Till about the year 1649 'twas held a strange presumption for a man to attempt an innovation of learning". The English apothecary was, of course, much influenced by these changes. He developed methods of inquiry and investigation, he experimented, he joined societies, he wrote to like-minded contemporaries, he published his findings, and, above all, he had the good fortune to be caught in the toils of collectors' mania, be it "curiosities" or new information. The apothecary had a particular interest in those fields that most closely impinged upon his own profession - botany, chemistry, and medicine. Although considerable advances in the description and classification of plants and animals had been made by 1760, no great theoretical principles or "laws" of biology had been developed. It should be noted, though, that the generation of scientists arriv- ing on the scene after 1760 was able to study an immensely richer collection of natural history specimens from distant lands, which helped towards developing new interpretations of Nature based on sounder doctrines. -

Studia Linguistica Universitatis Iagellonicae Cracoviensis 2019

Studia Linguistica Universitatis Iagellonicae Cracoviensis 136 (2019): 1–7 doi:10.4467/20834624SL.19.001.10244 www.ejournals.eu/Studia-Linguistica JOHN CONSIDINE University of Alberta, Edmonton [email protected] THE ORIGINS OF ENGLISH GUINEA PIG AND GERMAN MEERSCHWEINCHEN AGAIN Keywords: etymology, English language, German language, post-classical Latin lan- guage, biological terminology Abstract This is a note to support and expand recent work on the etymology of GermanMeer schwein chen, English guinea pig, and related forms with a body of dated evidence, in- cluding new first attestations for English guinea pig and Polish świnka morska. “Is the English guinea pig a pig from Guinea, and the German Meerschweinchen a piggy from the sea?” Marek Stachowski has asked (Stachowski 2014), returning to the question with a supplemental note on English guinea pig (Stachowski 2018). As he points out, “one cannot but wonder why this small animal, so utterly different from a pig, is nevertheless called a pig, as well as why it should be a pig from Guinea if it does not live in Guinea at all” (Stachowski 2014: 221). Its names in English and German are indeed puzzling. Stachowski’s masterly presentation and analysis of the evidence can, I think, be taken even further by a consideration of the dates at which some of the evidence is attested. Let us begin with the second element, pig. Stachowski (2014: 222) notes that “the animal is called a pig also in quite a few other languages (e.g. German Meer schweinchen …)”, and discusses the possible relevance of German Meerschwein ‘capybara’. -

The 100 Most Influential Scientists of All Time / Edited by Kara Rogers.—1St Ed

Published in 2010 by Britannica Educational Publishing (a trademark of Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.) in association with Rosen Educational Services, LLC 29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010. Copyright © 2010 Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, and the Thistle logo are registered trademarks of Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. All rights reserved. Rosen Educational Services materials copyright © 2010 Rosen Educational Services, LLC. All rights reserved. Distributed exclusively by Rosen Educational Services. For a listing of additional Britannica Educational Publishing titles, call toll free (800) 237-9932. First Edition Britannica Educational Publishing Michael I. Levy: Executive Editor Marilyn L. Barton: Senior Coordinator, Production Control Steven Bosco: Director, Editorial Technologies Lisa S. Braucher: Senior Producer and Data Editor Yvette Charboneau: Senior Copy Editor Kathy Nakamura: Manager, Media Acquisition Kara Rogers: Senior Editor, Biomedical Sciences Rosen Educational Services Jeanne Nagle: Senior Editor Nelson Sá: Art Director Introduction by Kristi Lew Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The 100 most influential scientists of all time / edited by Kara Rogers.—1st ed. p. cm.—(The Britannica guide to the world’s most influential people) “In association with Britannica Educational Publishing, Rosen Educational Services.” Includes index. ISBN 978-1-61530-040-2 (eBook) 1. Science—Popular works. 2. Science—History—Popular works. 3. Scientists— Biography—Popular works. I. Rogers, Kara. -

Engraving the Herball: Frontispieces and the Visual Understanding of Botany in 16Th – 17Th Century England

Engraving The Herball: Frontispieces and the visual understanding of botany in 16th – 17th century England Kaleigh Hunter S2052296 Supervisor: Dr. Marika Keblusek Second Reader: Dr. Stijn Bussels Master Museums & Collections 2017 / 2018 Contents INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................................... 1 CHAPTER 1: LEADING UP TO THE HERBALL ............................................................................................. 5 CHAPTER 2: THE FIRST FRONTISPIECE, 1597 ...................................................................................... 11 CHAPTER 3: THE TRANSITION .................................................................................................................... 25 CHAPTER 4 : THE NEW FRONTISPIECE, 1633 ....................................................................................... 29 CHAPTER 5: AFTER THE HERBALL ............................................................................................................. 35 CONCLUSION ....................................................................................................................................................... 37 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS ................................................................................................................................ 39 BIBLIOGRAPHY ..................................................................................................................................................