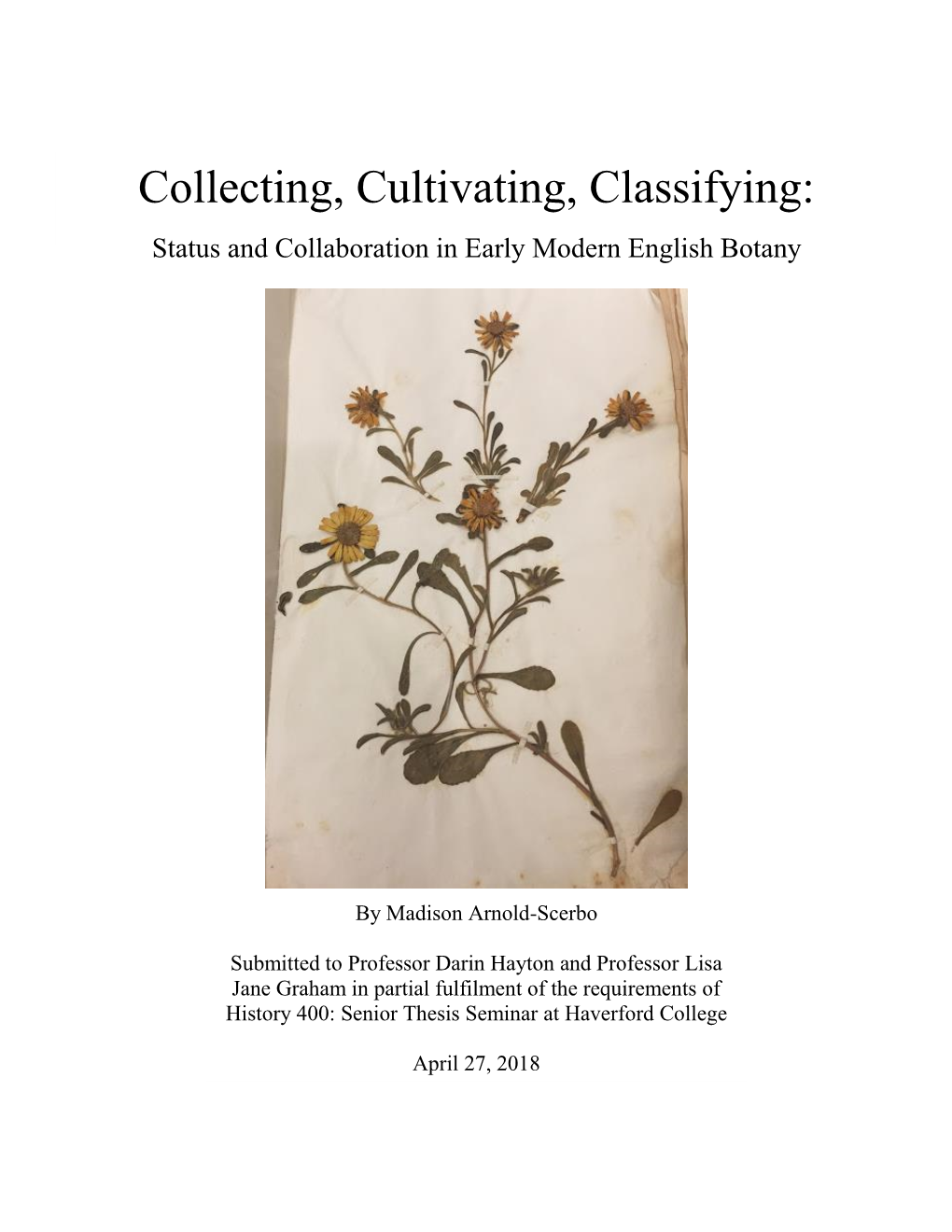

Collecting, Cultivating, Classifying: Status and Collaboration in Early Modern English Botany

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 2 Fundamental Questions: Linneaus and Kirchner

2/1/2011 The 2 fundamental questions: y Has evolution taken pp,lace, and if so, what is the Section 4 evidence? Professor Donald McFarlane y If evolution has taken place, what is the mechanism by which it works? Lecture 2 Evolutionary Ideas Evidence for evolution before Darwin Golden Age of Exploration y Magellan’s voyage –1519 y John Ray –University of y Antonius von Leeuwenhoek ‐ microbes –1683 Cambridge (England) y “Catalog of Cambridge Plants” – 1660 –lists 626 species y 1686 –John Ray listing thousands of plant species! y In 1678, Francis Willoughby publishes “Ornithology” Linneaus and Kirchner Athenasius Kircher ~ 1675 –Noah’s ark Carl Linneaus – Sistema Naturae ‐ 1735 Ark too small!! Uses a ‘phenetic” classification – implies a phylogenetic relationship! 300 x 50 x 30 cubits ~ 135 x 20 x 13 m 1 2/1/2011 y Georges Cuvier 1769‐ 1832 y “Fixity of Species” Evidence for Evolution –prior to 1830 • Enormous diversity of life –WHY ??? JBS Haldane " The Creator, if He exists, has "an inordinate fondness for beetles" ". Evidence for Evolution –prior to 1830 Evidence for Evolution –prior to 1830 y The discovery of variation. y Comparative Anatomy. Pentadactyl limbs Evidence for Evolution –prior to Evidence for Evolution –prior to 1830 1830 y Fossils – homologies with living species y Vestigal structures Pentadactyl limbs !! 2 2/1/2011 Evidence for Evolution –prior to 1830 Evidence for Evolution –prior to 1830 y Invariance of the fossil sequence y Plant and animal breeding JBS Haldane: “I will give up my belief in evolution if someone finds a fossil rabbit in the Precambrian.” Charles Darwin Jean Baptiste Lamark y 1744‐1829 y 1809 –1882 y Organisms have the ability to adapt to their y Voyage of Beagle 1831 ‐ 1836 environments over the course of their lives. -

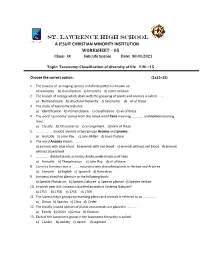

ST. LAWRENCE HIGH SCHOOL a JESUIT CHRISTIAN MINORITY INSTITUTION WORKSHEET – 05 Class: IX Sub: Life Science Date: 30.01.2021

ST. LAWRENCE HIGH SCHOOL A JESUIT CHRISTIAN MINORITY INSTITUTION WORKSHEET – 05 Class: IX Sub: Life Science Date: 30.01.2021 Topic: Taxonomy-Classification of diversity of life F.M. : 15 Choose the correct option: (1x15=15) 1. The process of arranging species in definite pattern is known as: a) taxonomy b) classification c) hierarchy d) nomenclature 2. The branch of biology which deals with the grouping of plants and animals is called …….. a) Nomenclature b) structural hierarchy c) taxonomy d) all of these 3. The study of taxonomy includes: a) Identification b) nomenclature c) classification d) all of these 4. The word ‘taxonomy’ comes from the Greek word Taxis meaning ………….. and nomos meaning laws: a) Classify b) Characterize c) arrangement d)none of these 5. ……………….. divided animals in two groups Anaima and Enaima . a) Aristotle b) John Ray c) John Miller d) Louis Pasteur 6. The word Anaima means …...... a) animals with blue blood b) animals with red blood c) animals without red blood d) animals without blue blood 7. ……………. divided plants as herbs,shrubs,undershrubs and trees. a) Aristotle b) Theophrastus c) John Ray d) all of these 8. Carrolus Linnaeus was a ……… naturalist who classisfied plants in Herbae and Arborea. a) Swedish b) English c) Spainish d) Australian 9. Linnaeus classified plants in in the following book: a) Species Plantarum b) Species Naturae c) Species plantae d) Species herbae 10. In which year did Linnaeus classified animals in Systema Naturae? a) 1753 b) 1758 c) 1756 d) 1769 11. The lowest major group representing plants and animals is referred to as …………… a) Genus b) Species c) Class d) Order 12. -

Biographical Appendix

Biographical Appendix The following women are mentioned in the text and notes. Abney- Hastings, Flora. 1854–1887. Daughter of 1st Baron Donington and Edith Rawdon- Hastings, Countess of Loudon. Married Henry FitzAlan Howard, 15th Duke of Norfolk, 1877. Acheson, Theodosia. 1882–1977. Daughter of 4th Earl of Gosford and Louisa Montagu (daughter of 7th Duke of Manchester and Luise von Alten). Married Hon. Alexander Cadogan, son of 5th Earl of Cadogan, 1912. Her scrapbook of country house visits is in the British Library, Add. 75295. Alten, Luise von. 1832–1911. Daughter of Karl von Alten. Married William Montagu, 7th Duke of Manchester, 1852. Secondly, married Spencer Cavendish, 8th Duke of Devonshire, 1892. Grandmother of Alexandra, Mary, and Theodosia Acheson. Annesley, Katherine. c. 1700–1736. Daughter of 3rd Earl of Anglesey and Catherine Darnley (illegitimate daughter of James II and Catherine Sedley, Countess of Dorchester). Married William Phipps, 1718. Apsley, Isabella. Daughter of Sir Allen Apsley. Married Sir William Wentworth in the late seventeenth century. Arbuthnot, Caroline. b. c. 1802. Daughter of Rt. Hon. Charles Arbuthnot. Stepdaughter of Harriet Fane. She did not marry. Arbuthnot, Marcia. 1804–1878. Daughter of Rt. Hon. Charles Arbuthnot. Stepdaughter of Harriet Fane. Married William Cholmondeley, 3rd Marquess of Cholmondeley, 1825. Aston, Barbara. 1744–1786. Daughter and co- heir of 5th Lord Faston of Forfar. Married Hon. Henry Clifford, son of 3rd Baron Clifford of Chudleigh, 1762. Bannister, Henrietta. d. 1796. Daughter of John Bannister. She married Rev. Hon. Brownlow North, son of 1st Earl of Guilford, 1771. Bassett, Anne. Daughter of Sir John Bassett and Honor Grenville. -

Ministers of ‘The Black Art’: the Engagement of British Clergy with Photography, 1839-1914

Ministers of ‘the Black Art’: the engagement of British clergy with photography, 1839-1914 Submitted by James Downs to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in March 2018 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signature: ………………………………………………………….. Abstract 1 Ministers of ‘the Black Art’: the engagement of British clergy with photography, 1839- 1914 This thesis examines the work of ordained clergymen, of all denominations, who were active photographers between 1839 and the beginning of World War One: its primary aim is to investigate the extent to which a relationship existed between the religious culture of the individual clergyman and the nature of his photographic activities. Ministers of ‘the Black Art’ makes a significant intervention in the study of the history of photography by addressing a major weakness in existing work. Taking an interdisciplinary approach, the research draws on a wide range of primary and secondary sources such as printed books, sermons, religious pamphlets, parish and missionary newsletters, manuscript diaries, correspondence, notebooks, biographies and works of church history, as well as visual materials including original glass plate negatives, paper prints and lantern slides held in archival collections, postcards, camera catalogues, photographic ephemera and photographically-illustrated books. -

The Charles Knight-Joseph Hooker Correspondence

A man tenax propositi: transcriptions of letters from Charles Knight to William Jackson Hooker and Joseph Dalton Hooker between 1852 and 1883 David J. Galloway Hon. Research Associate Landcare Research, and Te Papa Tongarewa [email protected] Geoscience Society of New Zealand miscellaneous publication 133J December 2013 Published by the Geoscience Society of New Zealand Inc, 2013 Information on the Society and its publications is given at www.gsnz.org.nz © Copyright David J. Galloway, 2013 Geoscience Society of New Zealand miscellaneous publication 133J ISBN 978-1-877480-36-2 ISSN 2230-4495 (Online) ISSN 2230-4487 (Print) This document is available as a PDF file that can be downloaded from the Geoscience Society website at: http://www.gsnz.org.nz/information/misc-series-i-49.html Bibliographic Reference Galloway D.J. 2013: A man tenax propositi: transcriptions of letters from Charles Knight to William Jackson Hooker and Joseph Dalton Hooker between 1852 and 1883 Geoscience Society of New Zealand miscellaneous publication 133J. 88 pages. A man tenax propositi: transcriptions of letters from Charles Knight to William Jackson Hooker and Joseph Dalton Hooker between 1852 and 1883 Contents Introduction 3 Charles Knight correspondence at Kew 5 Acknowledgements 6 Summaries of the letters 7 Transcriptions of the letters from Charles Knight 15 Footnotes 70 References 77 Figure 1: Dr Charles Knight FLS, FRCS 2 Figure 2: Group photograph including Charles Knight 2 Figure 3: Page of letter from Knight to Hooker 14 Table 1: Comparative chronology of Charles Knight, W.J. Hooker and J.D. Hooker 86 1 Figure 1: Dr Charles Knight FLS, FRCS Alexander Turnbull Library,Wellington, New Zealand ¼-015414 Figure 2: Group taken in Walter Mantell‟s garden about 1865 showing Charles Knight (left), John Buchanan and James Hector (right) and Walter Mantell and his young son, Walter Godfrey Mantell (seated on grass). -

History of Taxonomy

History of Taxonomy The history of taxonomy dates back to the origin of human language. Western scientific taxonomy started in Greek some hundred years BC and are here divided into prelinnaean and postlinnaean. The most important works are cited and the progress of taxonomy (with the focus on botanical taxonomy) are described up to the era of the Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus, who founded modern taxonomy. The development after Linnaeus is characterized by a taxonomy that increasingly have come to reflect the paradigm of evolution. The used characters have extended from morphological to molecular. Nomenclatural rules have developed strongly during the 19th and 20th century, and during the last decade traditional nomenclature has been challenged by advocates of the Phylocode. Mariette Manktelow Dept of Systematic Biology Evolutionary Biology Centre Uppsala University Norbyv. 18D SE-752 36 Uppsala E-mail: [email protected] 1. Pre-Linnaean taxonomy 1.1. Earliest taxonomy Taxonomy is as old as the language skill of mankind. It has always been essential to know the names of edible as well as poisonous plants in order to communicate acquired experiences to other members of the family and the tribe. Since my profession is that of a systematic botanist, I will focus my lecture on botanical taxonomy. A taxonomist should be aware of that apart from scientific taxonomy there is and has always been folk taxonomy, which is of great importance in, for example, ethnobiological studies. When we speak about ancient taxonomy we usually mean the history in the Western world, starting with Romans and Greek. However, the earliest traces are not from the West, but from the East. -

Middleton and John Ray Jo Walker from Middleton Hall on the Story Behind an Historic and Rare Rose

Middleton and John Ray Jo Walker from Middleton Hall on the story behind an historic and rare rose Middleton Hall is a Grade ‘Historia Piscium’ were II* listed manor with a published after his death by John Ray. John Ray tutored museum housed in Francis’ children whilst he buildings spanning 750 stayed at Middleton Hall and years of architectural remained at the Hall for a Rose “John Ray” is believed to survive styles. The surrounding number of years after Francis’ only in Middleton Hall’s walled garden estate covers 42 acres and death. It was at Middleton that he developed his original works includes a Site of Special on Natural History including his was gradually superseded by the Scientific Interest, a walled ‘History of Plants’. garden and shops. Now Linnean method which was first John Ray (1627-1705) applied to English botany in Dr J. restored the Hall is run by Philosopher and writer, cleric, Hill’s Flora Britannica 1760. a small independent traveller and taxonomist, Ray enjoyed the advantage of a charitable trust. Middleton deserves a wider reputation. His very long period of productive botanical works - ‘Historiae Hall has had a wide variety activity: in the thirty-four years Plantum’ and ‘Methodus of owners and tenants. that separated his Tables of Plantarum Nova’, were published Plants from his Methodus Two of our most famous 1682. Emendata et Aucta, he had time residents were the great Known as the father of English to revise and remodel his naturalists Francis Willughby natural history, John Ray’s system. (who spelt his name this way) system of plant classification and his tutor, friend and During his residence in became more popular than that collaborator John Ray. -

The Life and Times of a Curiosity-Monger

COMMENT BOOKS & ARTS Like Close, astronomer John MUSEUMS Dvorak hopscotches through eclipses in Mask of the Sun, but this is science his- tory rather than anecdote. The quotes he interweaves reveal the extraordinary The life and times of a pull the events have had on the human imagination. The writer Virginia Woolf, for instance, who had witnessed the 1927 curiosity-monger total solar eclipse in the north of England, wrote of it in her essay ‘The sun and the Henry Nicholls revels in a biography of Enlightenment fish’ the following year: “Show me the collector and Royal Society president Hans Sloane. eclipse, we say to the eye; let us see that strange spectacle again.” It’s a rich chronicle. Dvorak notes, for hat do bloodletting, slavery, instance, how in 1684 Increase Mather, journal editing and a silver penis the president of Harvard College in Cam- protector have in common? The bridge, Massachusetts, delayed the gradu- Weighteenth-century physician, collector and ation ceremony by ten days so that faculty president of the Royal Society Hans Sloane. PHOTOS.COM/GETTY members and students could reach Mar- In Collecting the World, historian James tha’s Vineyard off the state’s south coast Delbourgo charts Sloane’s rags-to-riches to see a total eclipse. (Mather, a Puritan transformation, from his birth in 1660 into minister, was less enlightened about the a family of domestic servants in the north Salem witch trials less than a decade later, of Ireland, to his death in 1753 as one of the refusing to condemn them.) We see how most influential figures in England. -

THE MAN of SCIENCE Steven Shapin

THE IMAGE OF THE MAN OF SCIENCE Steven Shapin The relations between the images of the man of science and the social and cultural realities of scientific roles are both consequential and contingent. Finding out “who the guys were” (to use Sir Lewis Namier’s phrase) does in- deed help to illuminate what kinds of guys they were thought to be, and, for that reason alone, any survey of images is bound to deal – to some extent at least – with what are usually called the realities of social roles.1 At the same time, it must be noted that such social roles are always very substantially con- stituted, sustained, and modified by what members of the culture think is, or should be, characteristic of those who occupy the roles, by precisely whom this is thought, and by what is done on the basis of such thoughts. In socio- logical terms of art, the very notion of a social role implicates a set of norms and typifications – ideals, prescriptions, expectations, and conventions thought properly, or actually, to belong to someone performing an activity of a certain kind. That is to say, images are part of social realities, and the two notions can be distinguished only as a matter of convention. Such conventional distinctions may be useful in certain circumstances. So- cial action – historical and contemporary – very often trades in juxtapositions between image and reality. One might hear it said, for example, that modern American lawyers do not really behave like the high-minded professionals 1 For introductions to pertinent prosopography, see, e.g., Robert M. -

The Dukes: Origins, Ennoblement and History of 26 Families PDF Book

THE DUKES: ORIGINS, ENNOBLEMENT AND HISTORY OF 26 FAMILIES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Brian Masters | 416 pages | 01 Feb 2001 | Vintage Publishing | 9780712667241 | English | London, United Kingdom The Dukes: Origins, Ennoblement and History of 26 Families PDF Book Spine still tight, in very good condition. No library descriptions found. The Telegraph. Richard Curzon-Howe, 1st Earl Howe Haiku summary. References to this work on external resources. Lord High Constable. He even acquired his very own Egyptian sarcophogus to house his own mortal remains. Sign in Login Password remember me Lost password Sign up. Condition: GOOD. Elizabeth Dashwood. Baron Botetourt — However as it happened Henry predeceased him without issue, having succumbed to the dropsy on the 10th May , and so with the death of the 7th Duke on the 4th December , the title passed to his younger son Alfred William. Seller Inventory GRD Since the 1st Duke's only son had died in , when he had originally been awarded the title of duke in he ensured that the grant included a special remainder nominating his brother as heir should he fail to produce any male issue. Charles Montagu. Published by Penguin Random House This line was of knightly origin and probably a branch of the baronial Montagus Earls of Salisbury from , whose almost certain ancestor Dru de Montagud was a tenant-in-chief in The Montagus of Boughton, Northhamptonshire, who acquired a barony in , an earldom in , the dukedom of Montagu in , and in their younger branches the earldom of Manchester in , the dukedom of Manchester in , and the earldom of Sandwich in , descended from Richard Montagu alias Ladde, a yeoman or husbandman, living in at Hanging Houghton, Northamptonshire, where the Laddes had been tenants since the fourteenth century. -

John Ray's Natural History Travels

t rith .,-c!.& a,Yr Stcoe"'r k*:'t r{-dr-aa Cr'.t r<. pp Vq-5r'.) JOHNRAY'S NATURAL HISTORY TRAVELS II.I BRITA]N By Professor WIILIA.II T. STEARN c/o Depa.tnent of Botang, aritjsi ltuse ? (Natutal Eistory) gotanical Socieayof the British Islcs ConferenceReport No. 20 Rend l3th Scptenbcr l9E6 Repr't-r,teCfron TheScottish llatural ist 1986, plgcs 43-57 1985 Jaln Rag's lvatural ,gistorg Ttavels in Britain JOHNRAY'S NATURAL HISTORY TRAVELS IN BRITAIN By WTLLIAM T. STEARN c/o Departnent of Botang, alitish ]tluseun (NaturaT Histotg ) Introduct'ion John Ray, the nost distinguished British naturalist of the ITth century, was boln in 1628 in a Iittle English vil1a8e, Black Notley, near Braintiee, Essex, and thele he died in 1707 (Raven 1942, Baldrin 1986). His publications on botanyr zoology and theology br:ought hin international renown; they are so nulelous that the description of their editions proved a fornidable task even for so experienced and distinguished a bibliographer as Si! Geoffrey (eynes. He wroterrlt nay be that I should never have atternpted to conpile a full-scal.e bibliography of his works; but the versatility of his attai nents, lhe variety of his books, and the real nobility of his character nade hirn irresistibletr. Keynes' detailed work thus brings for\,iard "evidence in a bibliographical dress of his nodesty, his loyalty, and his integrity'r (Keynes1951: ix). Ray was also the nost tTavelled British naturalist of his century, toSethei with his friend Si! Flancis l{iIlughby (1635-1672). Rayrs travels extended fron Stirling in Scotland to Malta and Sicily, where he climbed Mount Etna up to the snow-line. -

A Guide to the Pictures at Powis Castle Dr Peter Moore a Guide to the Pictures at Powis Castle by Dr Peter Moore

A Guide to the Pictures at Powis Castle Dr Peter Moore A Guide to the Pictures at Powis Castle by Dr Peter Moore Contents A Guide to the Pictures at Powis Castle 3 The Pictures 4 The Smoking Room 4 The State Dining Room 5 The Library 10 The Oak Drawing Room 13 The Gateway 18 The Long Gallery 20 The Walcot Bedroom 24 The Gallery Bedroom 26 The Duke’s Room 26 The Lower Tower Bedroom 28 The Blue Drawing Room 30 The Exit Passage 37 The Clive Museum 38 The Staircase 38 The Ballroom 41 Acknowledgements 48 2 Above Thomas Gainsborough RA, c.1763 Edward Clive, 1st Earl of Powis III as a Boy See page 13 3 Introduction Occupying a grand situation, high up on One of the most notable features of a rocky prominence, Powis Castle began the collection is the impressive run of life as a 13th-century fortress for the family portraits, which account for nearly Welsh prince, Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn. three-quarters of the paintings on display. However, its present incarnation dates From the earliest, depicting William from the 1530s, when Edward Grey, Lord Herbert and his wife Eleanor in 1595, Powis, took possession of the site and to the most recent, showing Christian began a major rebuilding programme. Herbert in 1977, these images not only The castle he created soon became help us to explore and understand regarded as the most imposing noble very intimate personal stories, but also residence in North and Central Wales. speak eloquently of changing tastes in In 1578, the castle was leased to Sir fashion and material culture over an Edward Herbert, the second son of extraordinarily long timespan.