The Charles Knight-Joseph Hooker Correspondence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Taxonomy and New Records of Graphidaceae Lichens in Western Pangasinan, Northern Philippines

PRIMARY RESEARCH PAPER | Philippine Journal of Systematic Biology DOI 10.26757/pjsb2019b13006 Taxonomy and new records of Graphidaceae lichens in Western Pangasinan, Northern Philippines Weenalei T. Fajardo1, 2* and Paulina A. Bawingan1 Abstract There are limited studies on the diversity of Philippine lichenized fungi. This study collected and determined corticolous Graphidaceae from 38 collection sites in 10 municipalities of western Pangasinan province. The study found 35 Graphidaceae species belonging to 11 genera. Graphis is the dominant genus with 19 species. Other species belong to the genera Allographa (3 species) Fissurina (3), Phaeographis (3), while Austrotrema, Chapsa, Diorygma, Dyplolabia, Glyphis, Ocellularia, and Thelotrema had one species each. This taxonomic survey added 14 new records of Graphidaceae to the flora of western Pangasinan. Keywords: Lichenized fungi, corticolous, crustose lichens, Ostropales Introduction described Graphidaceae in the country (Parnmen et al. 2012). Most recent surveys resulted in the characterization of six new Graphidaceae is the second largest family of lichenized species (Lumbsch et al. 2011; Tabaquero et al.2013; Rivas-Plata fungi (Ascomycota) (Rivas-Plata et al. 2012; Lücking et al. et al. 2014). In the northwestern part of Luzon in the Philippines 2017) and is the most speciose of tropical crustose lichens (Region 1), an account on the Graphidaceae lichens was (Staiger 2002; Lücking 2009). The inclusion of the initially conducted only from the Hundred Islands National Park (HINP), separate family Thelotremataceae (Mangold et al. 2008; Rivas- Alaminos City, Pangasinan (Bawingan et al. 2014). The study Plata et al. 2012) in the family Graphidaceae made the latter the reported 32 identified lichens, including 17 Graphidaceae dominant element of lichen communities with 2,161 accepted belonging to the genera Diorygma, Fissurina, Graphis, Thecaria species belonging to 79 genera (Lücking et al. -

Phytochimie De Lichens Du Genre Stereocaulon : Étude Particulière De S

Phytochimie de lichens du genre Stereocaulon : étude particulière de S. Halei Lamb et S. montagneanum Lamb, deux lichens recoltés en Indonésie Friardi Ismed To cite this version: Friardi Ismed. Phytochimie de lichens du genre Stereocaulon : étude particulière de S. Halei Lamb et S. montagneanum Lamb, deux lichens recoltés en Indonésie. Sciences pharmaceutiques. Université Rennes 1, 2012. Français. NNT : 2012REN1S053. tel-00737382 HAL Id: tel-00737382 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-00737382 Submitted on 1 Oct 2012 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. N° d’ordre : 4924 ANNÉE 2012 THÈSE / UNIVERSITÉ DE RENNES 1 sous le sceau de l’Université Européenne de Bretagne pour le grade de DOCTEUR DE L’UNIVERSITÉ DE RENNES 1 Mention : Chimie Ecole doctorale Sciences De La Matière présentée par Friardi Ismed Préparée dans l’unité de recherche UMR CNRS 6226 Equipe PNSCM (Produits Naturels Synthèses Chimie Médicinale) (Faculté de Pharmacie, Université de Rennes1) Thèse soutenue à Rennes Phytochimie de le 12 Juillet 2012 lichens du genre Stereocaulon: étude devant le jury composé de : Nathalie BOURGOUGNON Professeur à l’Université de Bretagne-Sud/ particulière de rapporteur Elisabeth SEGUIN S. -

Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy by George Biddell Airy 1

Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy by George Biddell Airy 1 CHAPTER I. CHAPTER II. CHAPTER III. CHAPTER IV. CHAPTER V. CHAPTER VI. CHAPTER VII. CHAPTER VIII. CHAPTER IX. CHAPTER X. CHAPTER I. CHAPTER II. CHAPTER III. CHAPTER IV. CHAPTER V. CHAPTER VI. CHAPTER VII. CHAPTER VIII. CHAPTER IX. CHAPTER X. Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy by George Biddell Airy The Project Gutenberg EBook of Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy by George Biddell Airy This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy by George Biddell Airy 2 License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy Author: George Biddell Airy Release Date: January 9, 2004 [EBook #10655] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SIR GEORGE AIRY *** Produced by Joseph Myers and PG Distributed Proofreaders AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF SIR GEORGE BIDDELL AIRY, K.C.B., M.A., LL.D., D.C.L., F.R.S., F.R.A.S., HONORARY FELLOW OF TRINITY COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE, ASTRONOMER ROYAL FROM 1836 TO 1881. EDITED BY WILFRID AIRY, B.A., M.Inst.C.E. 1896 PREFACE. The life of Airy was essentially that of a hard-working, business man, and differed from that of other hard-working people only in the quality and variety of his work. It was not an exciting life, but it was full of interest, and his work brought him into close relations with many scientific men, and with many men high in the State. -

The Lichen Genus <I>Fissurina</I>

ISSN (print) 0093-4666 © 2013. Mycotaxon, Ltd. ISSN (online) 2154-8889 MYCOTAXON http://dx.doi.org/10.5248/124.309 Volume 124, pp. 309–321 April–June 2013 The lichen genus Fissurina (Graphidaceae) in Vietnam Santosh Joshi1, Thi Thuy Nguyen2, Nguyen Anh Dzung2, Udeni Jayalal1, Soon-Ok Oh1 & Jae-Seoun Hur1* 1Korean Lichen Research Institute, Sunchon National University, Suncheon-540 742, Korea 2Biotechnology Center, Tay Nguyen University, 567 Le Duan, Buon Ma Thuot City, Vietnam Correspondence to *: [email protected] Abstract — Nine species of Fissurina from Vietnam are briefly commented on. Fissurina dumastii, F. dumastioides, F. instabilis, F. rubiginosa, and F. undulata are recorded as new for the Vietnam lichen biota. Characteristic morpho-anatomical and chemical features are described and summarized in an artificial key to all known taxa of Fissurina from Vietnam. Key words — Chu Yang Sin National Park, corticolous, graphidoid, taxonomy Introduction Fissurina Fée (Ascomycota: Ostropales) accommodates species with mostly slit-like lirellae (Staiger 2002; Archer 2009). The diagnostic characters of the genus includes a pale to yellow-brown to olive green (rarely whitish), mostly smooth and glossy thallus, fissurine, simple to branched, immersed to prominent lirellae, uncarbonized or rarely carbonized proper exciple, clear hyaline non- amyloid hymenium, 1–8-spored asci, and hyaline, oval or narrowly to broadly ellipsoid, trans-septate to muriform, amyloid to non-amyloid, thick-walled, mostly halonate ascospores (Archer 2009; Sharma et al. 2012). Fissurina occurs in the tropics and presently comprises more than 100 species worldwide. Many species have recently been added to the genus as a consequence of a molecular and phylogenetic revision of the Graphidaceae (Rivas Plata et al. -

The 2 Fundamental Questions: Linneaus and Kirchner

2/1/2011 The 2 fundamental questions: y Has evolution taken pp,lace, and if so, what is the Section 4 evidence? Professor Donald McFarlane y If evolution has taken place, what is the mechanism by which it works? Lecture 2 Evolutionary Ideas Evidence for evolution before Darwin Golden Age of Exploration y Magellan’s voyage –1519 y John Ray –University of y Antonius von Leeuwenhoek ‐ microbes –1683 Cambridge (England) y “Catalog of Cambridge Plants” – 1660 –lists 626 species y 1686 –John Ray listing thousands of plant species! y In 1678, Francis Willoughby publishes “Ornithology” Linneaus and Kirchner Athenasius Kircher ~ 1675 –Noah’s ark Carl Linneaus – Sistema Naturae ‐ 1735 Ark too small!! Uses a ‘phenetic” classification – implies a phylogenetic relationship! 300 x 50 x 30 cubits ~ 135 x 20 x 13 m 1 2/1/2011 y Georges Cuvier 1769‐ 1832 y “Fixity of Species” Evidence for Evolution –prior to 1830 • Enormous diversity of life –WHY ??? JBS Haldane " The Creator, if He exists, has "an inordinate fondness for beetles" ". Evidence for Evolution –prior to 1830 Evidence for Evolution –prior to 1830 y The discovery of variation. y Comparative Anatomy. Pentadactyl limbs Evidence for Evolution –prior to Evidence for Evolution –prior to 1830 1830 y Fossils – homologies with living species y Vestigal structures Pentadactyl limbs !! 2 2/1/2011 Evidence for Evolution –prior to 1830 Evidence for Evolution –prior to 1830 y Invariance of the fossil sequence y Plant and animal breeding JBS Haldane: “I will give up my belief in evolution if someone finds a fossil rabbit in the Precambrian.” Charles Darwin Jean Baptiste Lamark y 1744‐1829 y 1809 –1882 y Organisms have the ability to adapt to their y Voyage of Beagle 1831 ‐ 1836 environments over the course of their lives. -

Australasian Lichenology Number 56, January 2005

Australasian Lichenology Number 56, January 2005 Australasian Lichenology Number 56, January 2005 ISSN 1328-4401 The Austral Pannaria immixta c.olonizes rock, bark, and occasionally bryophytes in both shaded and well-lit humid lowlands. Its two most distinctive traits are its squamulose thallus and its gyrose apothecial discs. 1 mm c:::::===- CONTENTS NEWS Kantvilas, ~ack Elix awarded the Acharius medal at IAL5 2 BOOK REVIEW Galloway, DJ-The Lichen Hunters, by Oliver Gilbert (2004) 4 RECENT LITERATURE ON AUSTRALASIAN LICHENS 7 ADDITIONAL LICHEN RECORDS FROM AUSTRALIA Elix, JA; Lumbsch, HT (55)-Diploschistes conception is 8 ARTICLES Archer, AW-Australian species in the genus Diorygma (Graphidaceae) ....... 10 Elix, JA; Blanco, 0; Crespo, A-A new species of Flauoparmelia (Parmeliaceae, lichenized Ascomycota) from Western Australia ...... .... ............................ ...... 12 Galloway, DJ; Sancho, LG-Umbilicaria murihikuana and U. robusta (Umbili cariaceae: Ascomycota), two new taxa from Aotearoa New Zealand .. ... .. ..... 16 Elix, JA; Bawingan, PA; Lardizaval, M; Schumm, F-Anew species ofMenegazzia (Parmeliaceae, lichenized Ascomycota) and new records of Parmeliaceae from Papua New Guinea and the Philippines .................................. .. .................... 20 Malcolm, WM-'ITansfer ofDimerella rubrifusca to Coenogonium ........ ......... 25 Johnson, PN- Lichen succession near Arthur's Pass, New Zealand ............... 26 NEWS JACK ELIXAWARDED THE ACHARIUS MEDALAT IAL5 The recent Fifth Conference of the International Association for Lichenology (1AL5) in Tartu, Estonia, was a highly successful event, and most Australasian lichenologists will have the opportunity to read of its various academic achieve ments in other media*. The social programme included the traditionallAL Din ner, where, after many days of symposia, poster sessions, excursions, meetings and other lichenological events, conference delegates mingle informally and dust away their weariness over food and drink. -

A Tribute to Oliver Lathe Gilbert

The Lichenologist 37(6): 467–475 (2005) 2005 The British Lichen Society doi:10.1017/S0024282905900042 Printed in the United Kingdom A tribute to Oliver Lathe Gilbert 7 September 1936–15 May 2005 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.33.42, on 02 Oct 2021 at 19:57:54, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0024282905900042 468 THE LICHENOLOGIST Vol. 37 Oliver Gilbert was a pioneer, an outstanding books on mountaineering and hill walking field botanist and inspirational scientist. He including the now classic ‘Big Walks’, worked in the broad fields of urban and ‘Classic Walks’ and ‘Wild Walks’ and the lichen ecology and had almost 40 years of award winning ‘Exploring the Far North teaching and research experience within West of Scotland’. His uncle was the universities. Above all he was very approach- mycologist Geoffrey Ainsworth, a former able, an excellent teacher and fun to be with. Director of the (former) International Oliver was a leading figure in the British Mycological Institute and author of several Lichen Society serving as BLS Bulletin classic texts on mycology. Oliver’s literary Editor (1980–89 except 1987), President talents, following a fine family tradition, (1976–77) and was a frequent Council likewise later excelled. Member. He was elected an Honorary After the war his family moved to Member in 1997 and received the prestig- Harpenden where he attended St Georges ious Ursula Duncan Award in January 2004. School. As St Georges did not offer ‘A’ level Oliver had an exceptional ability to find rare Biology, his parents sent him to Watford and interesting lichens and plant communi- Grammar School. -

The Correspondence of Julius Haast and Joseph Dalton Hooker, 1861-1886

The Correspondence of Julius Haast and Joseph Dalton Hooker, 1861-1886 Sascha Nolden, Simon Nathan & Esme Mildenhall Geoscience Society of New Zealand miscellaneous publication 133H November 2013 Published by the Geoscience Society of New Zealand Inc, 2013 Information on the Society and its publications is given at www.gsnz.org.nz © Copyright Simon Nathan & Sascha Nolden, 2013 Geoscience Society of New Zealand miscellaneous publication 133H ISBN 978-1-877480-29-4 ISSN 2230-4495 (Online) ISSN 2230-4487 (Print) We gratefully acknowledge financial assistance from the Brian Mason Scientific and Technical Trust which has provided financial support for this project. This document is available as a PDF file that can be downloaded from the Geoscience Society website at: http://www.gsnz.org.nz/information/misc-series-i-49.html Bibliographic Reference Nolden, S.; Nathan, S.; Mildenhall, E. 2013: The Correspondence of Julius Haast and Joseph Dalton Hooker, 1861-1886. Geoscience Society of New Zealand miscellaneous publication 133H. 219 pages. The Correspondence of Julius Haast and Joseph Dalton Hooker, 1861-1886 CONTENTS Introduction 3 The Sumner Cave controversy Sources of the Haast-Hooker correspondence Transcription and presentation of the letters Acknowledgements References Calendar of Letters 8 Transcriptions of the Haast-Hooker letters 12 Appendix 1: Undated letter (fragment), ca 1867 208 Appendix 2: Obituary for Sir Julius von Haast 209 Appendix 3: Biographical register of names mentioned in the correspondence 213 Figures Figure 1: Photographs -

An Evolving Phylogenetically Based Taxonomy of Lichens and Allied Fungi

Opuscula Philolichenum, 11: 4-10. 2012. *pdf available online 3January2012 via (http://sweetgum.nybg.org/philolichenum/) An evolving phylogenetically based taxonomy of lichens and allied fungi 1 BRENDAN P. HODKINSON ABSTRACT. – A taxonomic scheme for lichens and allied fungi that synthesizes scientific knowledge from a variety of sources is presented. The system put forth here is intended both (1) to provide a skeletal outline of the lichens and allied fungi that can be used as a provisional filing and databasing scheme by lichen herbarium/data managers and (2) to announce the online presence of an official taxonomy that will define the scope of the newly formed International Committee for the Nomenclature of Lichens and Allied Fungi (ICNLAF). The online version of the taxonomy presented here will continue to evolve along with our understanding of the organisms. Additionally, the subfamily Fissurinoideae Rivas Plata, Lücking and Lumbsch is elevated to the rank of family as Fissurinaceae. KEYWORDS. – higher-level taxonomy, lichen-forming fungi, lichenized fungi, phylogeny INTRODUCTION Traditionally, lichen herbaria have been arranged alphabetically, a scheme that stands in stark contrast to the phylogenetic scheme used by nearly all vascular plant herbaria. The justification typically given for this practice is that lichen taxonomy is too unstable to establish a reasonable system of classification. However, recent leaps forward in our understanding of the higher-level classification of fungi, driven primarily by the NSF-funded Assembling the Fungal Tree of Life (AFToL) project (Lutzoni et al. 2004), have caused the taxonomy of lichen-forming and allied fungi to increase significantly in stability. This is especially true within the class Lecanoromycetes, the main group of lichen-forming fungi (Miadlikowska et al. -

The Reverend Charles Samuel Pollock Parish-Plant

Lankesteriana International Journal on Orchidology ISSN: 1409-3871 [email protected] Universidad de Costa Rica Costa Rica Clayton, Dudley THE REVEREND CHARLES SAMUEL POLLOCK PARISH-PLANT COLLECTOR & BOTANICAL ILLUSTRATOR OF THE ORCHIDS FROM TENASSERIM PROVINCE, BURMA Lankesteriana International Journal on Orchidology, vol. 13, núm. 3, enero, 2013, pp. 215- 227 Universidad de Costa Rica Cartago, Costa Rica Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=44339826020 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative LANKESTERIANA 13(3): 215—227. 2014. I N V I T E D P A P E R* THE REVEREND CHARLES SAMUEL POLLOCK PARISH - PLANT COLLECTOR & BOTANICAL ILLUSTRATOR OF THE ORCHIDS FROM TENASSERIM PROVINCE, BURMA DUDLEY CLAYTON Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 3AB, United Kingdom [email protected] ABSTRACT. Charles Parish collected plants in Burma (now Myanmar) between 1852 and 1878. His orchid collections, both preserved and living plants, were extensive. He sent plant material and watercolour sketches to Sir William Hooker at Kew and living plants to the British orchid nursery of Messrs Hugh Low & Co. of Upper Clapton. H.G. Reichenbach obtained examples of the Parish plant material from Hugh Low and he visited Kew where he studied the Parish orchid specimens and illustrations and many of them were subsequently described by Reichenbach. His beautiful and accurate watercolour paintings of orchids were bound in two volumes and eventually came to Kew following his death. -

Mycology from the Library of Nils Fries

CENTRALANTIKVARIATET catalogue 82 MYCOLOGY from the library of nils fries CENTRALANTIKVARIATET catalogue 82 MYCOLOGY from the library of nils fries stockholm mmxvi 15 centralantikvariatet österlånggatan 53 111 31 stockholm +46 8 411 91 36 www.centralantikvariatet.se e-mail: [email protected] bankgiro 585-2389 medlem i svenska antikvariatföreningen member of ilab grafisk form och foto: lars paulsrud tryck: eo grafiska 2016 Vignette on title page from 194 PREFACE It is with great pleasure we are now able to present our Mycology catalogue, with old and rare books, many of them beautifully illustrated, about mushrooms. In addition to being fine mycological books in their own right, they have a great provenance, coming from the libraries of several members of the Fries family – the leading botanist and mycologist family in Sweden. All of the books are from the library of Nils Fries (1912–94), many from that of his grandfather Theodor (Thore) M. Fries (1832–1913), and a few from the library of Nils’ great grandfather Elias M. Fries (1794–1878), “fa- ther of Swedish mycology”. All three were botanists and professors at Uppsala University, as were many other members of the family, often with an orientation towards mycology. Nils Fries field of study was the procreation of mushrooms. Furthermore, Nils Fries has had a partiality for interesting provenances in his purchases – and many international mycologists are found among the former owners of the books in the catalogue. Four of the books are inscribed to Elias M. Fries, and it is probable that more of them come from his collection. Thore M. -

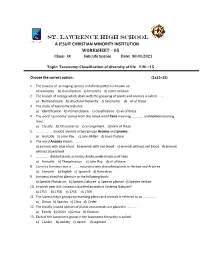

ST. LAWRENCE HIGH SCHOOL a JESUIT CHRISTIAN MINORITY INSTITUTION WORKSHEET – 05 Class: IX Sub: Life Science Date: 30.01.2021

ST. LAWRENCE HIGH SCHOOL A JESUIT CHRISTIAN MINORITY INSTITUTION WORKSHEET – 05 Class: IX Sub: Life Science Date: 30.01.2021 Topic: Taxonomy-Classification of diversity of life F.M. : 15 Choose the correct option: (1x15=15) 1. The process of arranging species in definite pattern is known as: a) taxonomy b) classification c) hierarchy d) nomenclature 2. The branch of biology which deals with the grouping of plants and animals is called …….. a) Nomenclature b) structural hierarchy c) taxonomy d) all of these 3. The study of taxonomy includes: a) Identification b) nomenclature c) classification d) all of these 4. The word ‘taxonomy’ comes from the Greek word Taxis meaning ………….. and nomos meaning laws: a) Classify b) Characterize c) arrangement d)none of these 5. ……………….. divided animals in two groups Anaima and Enaima . a) Aristotle b) John Ray c) John Miller d) Louis Pasteur 6. The word Anaima means …...... a) animals with blue blood b) animals with red blood c) animals without red blood d) animals without blue blood 7. ……………. divided plants as herbs,shrubs,undershrubs and trees. a) Aristotle b) Theophrastus c) John Ray d) all of these 8. Carrolus Linnaeus was a ……… naturalist who classisfied plants in Herbae and Arborea. a) Swedish b) English c) Spainish d) Australian 9. Linnaeus classified plants in in the following book: a) Species Plantarum b) Species Naturae c) Species plantae d) Species herbae 10. In which year did Linnaeus classified animals in Systema Naturae? a) 1753 b) 1758 c) 1756 d) 1769 11. The lowest major group representing plants and animals is referred to as …………… a) Genus b) Species c) Class d) Order 12.