THE MAN of SCIENCE Steven Shapin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Literature Compass Editing Humphry Davy's

1 ‘Work in Progress in Romanticism’ Literature Compass Editing Humphry Davy’s Letters Tim Fulford, Andrew Lacey, Sharon Ruston An editorial team of Tim Fulford (De Montfort University) and Sharon Ruston (Lancaster University) (co-editors), and Jan Golinski (University of New Hampshire), Frank James (the Royal Institution of Great Britain), and David Knight1 (Durham University) (advisory editors) are currently preparing The Collected Letters of Sir Humphry Davy: a four-volume edition of the c. 1200 surviving letters of Davy (1778-1829) and his immediate circle, for publication with Oxford University Press, in both print and electronic forms, in 2020. Davy was one of the most significant and famous figures in the scientific and literary culture of early nineteenth-century Britain, Europe, and America. Davy’s scientific accomplishments were varied and numerous, including conducting pioneering research into the physiological effects of nitrous oxide (laughing gas); isolating potassium, calcium, and several other metals; inventing a miners’ safety lamp (the bicentenary of which was celebrated in 2015); developing the electrochemical protection of the copper sheeting of Royal Navy vessels; conserving the Herculaneum papyri; writing an influential text on agricultural chemistry; and seeking to improve the quality of optical glass. But Davy’s endeavours were not merely limited to science: he was also a poet, and moved in the same literary circles as Lord Byron, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Robert Southey, and William Wordsworth. Since his death, Davy has rarely been out of the public mind. He is still the frequent subject of biographies (by, 1 David Knight died in 2018. David gave generously to the Davy Letters Project, and a two-day conference at Durham University was recently held in his memory. -

William Withering and the Introduction of Digitalis Into Medical Practice

[From Schenckius: Observationum Medicarum, Francofurti, 1609.] ANNALS OF MEDICAL HISTORY New Series , Volume VIII May , 1936 Numbe r 3 WILLIAM WITHERING AND THE INTRODUCTION OF DIGITALIS INTO MEDICAL PRACTICE By LOUIS H. RODDIS, COMMANDER, M.C., U.S.N. WASHINGTON, D. C. Part II* N interesting fea- as Dr. Fulton points out, there is no ture regarding the question that Darwin received his first early use of digi- acquaintancewithdigitalis from Wither- talis and the ques- ing. The evidence is indisputable as tion of the priority Withering himself cites the case (No. of Withering in its iv, M iss Hill) and says that Darwin was discovery, has been his consultant. Darwin mentions the brought out by case in his commonplace book but Professor John F. Fulton of Yale Uni- neither there nor in his published ac- versity School of Medicine. He has counts does he mention Withering’s shown that Erasmus Darwin, in an ap- name. His relations with Withering are pendix to the graduation thesis of his shown by some of his letters to have son Charles, which he published in been very unfriendly, at least after 1780, two years after Charles’ death. 1788, and he was probably jealous of gave some account of the use of fox- him. By our present standards Darwin’s glove with several case histories. March conduct in not mentioning Withering 16. 1785, Erasmus Darwin read a paper in either of his papers was distinctly which was dated January 14, 1785, and uncthical. which was published in the medical As he became more prosperous With- transactions, containing a reference to ering purchased a valuable piece of foxglove. -

Atomic History Project Background: If You Were Asked to Draw the Structure of an Atom, What Would You Draw?

Atomic History Project Background: If you were asked to draw the structure of an atom, what would you draw? Throughout history, scientists have accepted five major different atomic models. Our perception of the atom has changed from the early Greek model because of clues or evidence that have been gathered through scientific experiments. As more evidence was gathered, old models were discarded or improved upon. Your task is to trace the atomic theory through history. Task: 1. You will create a timeline of the history of the atomic model that includes all of the following components: A. Names of 15 of the 21 scientists listed below B. The year of each scientist’s discovery that relates to the structure of the atom C. 1- 2 sentences describing the importance of the discovery that relates to the structure of the atom Scientists for the timeline: *required to be included • Empedocles • John Dalton* • Ernest Schrodinger • Democritus* • J.J. Thomson* • Marie & Pierre Curie • Aristotle • Robert Millikan • James Chadwick* • Evangelista Torricelli • Ernest • Henri Becquerel • Daniel Bernoulli Rutherford* • Albert Einstein • Joseph Priestly • Niels Bohr* • Max Planck • Antoine Lavoisier* • Louis • Michael Faraday • Joseph Louis Proust DeBroglie* Checklist for the timeline: • Timeline is in chronological order (earliest date to most recent date) • Equal space is devoted to each year (as on a number line) • The eight (8) *starred scientists are included with correct dates of their discoveries • An additional seven (7) scientists of your choice (from -

The Lunar Society of Birmingham and the Practice of Science in 18Th Century Great Britain

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2011 The unL ar Society of Birmingham and the Practice of Science in 18th Century Great Britain Scott H. Zurawel Union College - Schenectady, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons Recommended Citation Zurawel, Scott H., "The unL ar Society of Birmingham and the Practice of Science in 18th Century Great Britain" (2011). Honors Theses. 1092. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/1092 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i THE LUNAR SOCIETY OF BIRMINGHAM AND THE PRACTICE OF SCIENCE IN 18TH CENTURY GREAT BRITAIN: A STUDY OF JOSPEH PRIESTLEY, JAMES WATT AND WILLIAM WITHERING By Scott Henry Zurawel ******* Submitted in partial fulfillment Of the requirements for Honors in the Department of History UNION COLLEGE March, 2011 ii ABSTRACT Zurawel, Scott The Lunar Society of Birmingham and the Practice of Science in Eighteenth-Century Great Britain: A Study of Joseph Priestley, James Watt, and William Withering This thesis examines the scientific and technological advancements facilitated by members of the Lunar Society of Birmingham in eighteenth-century Britain. The study relies on a number of primary sources, which range from the regular correspondence of its members to their various published scientific works. The secondary sources used for this project range from comprehensive books about the society as a whole to sources concentrating on particular members. -

The 2 Fundamental Questions: Linneaus and Kirchner

2/1/2011 The 2 fundamental questions: y Has evolution taken pp,lace, and if so, what is the Section 4 evidence? Professor Donald McFarlane y If evolution has taken place, what is the mechanism by which it works? Lecture 2 Evolutionary Ideas Evidence for evolution before Darwin Golden Age of Exploration y Magellan’s voyage –1519 y John Ray –University of y Antonius von Leeuwenhoek ‐ microbes –1683 Cambridge (England) y “Catalog of Cambridge Plants” – 1660 –lists 626 species y 1686 –John Ray listing thousands of plant species! y In 1678, Francis Willoughby publishes “Ornithology” Linneaus and Kirchner Athenasius Kircher ~ 1675 –Noah’s ark Carl Linneaus – Sistema Naturae ‐ 1735 Ark too small!! Uses a ‘phenetic” classification – implies a phylogenetic relationship! 300 x 50 x 30 cubits ~ 135 x 20 x 13 m 1 2/1/2011 y Georges Cuvier 1769‐ 1832 y “Fixity of Species” Evidence for Evolution –prior to 1830 • Enormous diversity of life –WHY ??? JBS Haldane " The Creator, if He exists, has "an inordinate fondness for beetles" ". Evidence for Evolution –prior to 1830 Evidence for Evolution –prior to 1830 y The discovery of variation. y Comparative Anatomy. Pentadactyl limbs Evidence for Evolution –prior to Evidence for Evolution –prior to 1830 1830 y Fossils – homologies with living species y Vestigal structures Pentadactyl limbs !! 2 2/1/2011 Evidence for Evolution –prior to 1830 Evidence for Evolution –prior to 1830 y Invariance of the fossil sequence y Plant and animal breeding JBS Haldane: “I will give up my belief in evolution if someone finds a fossil rabbit in the Precambrian.” Charles Darwin Jean Baptiste Lamark y 1744‐1829 y 1809 –1882 y Organisms have the ability to adapt to their y Voyage of Beagle 1831 ‐ 1836 environments over the course of their lives. -

Session Abstracts for 2013 HSS Meeting

Session Abstracts for 2013 HSS Meeting Sessions are sorted alphabetically by session title. Only organized sessions have a session abstract. Title: 100 Years of ISIS - 100 Years of History of Greek Science Abstract: However symbolic they may be, the years 1913-2013 correspond to a dramatic transformation in the approach to the history of ancient science, particularly Greek science. Whereas in the early 20th century, the Danish historian of sciences Johan Ludvig Heiberg (1854-1928) was publishing the second edition of Archimedes’ works, in the early 21st century the study of Archimedes' contribution has been dramatically transformed thanks to the technological analysis of the famous palimpsest. This session will explore the historiography of Greek science broadly understood during the 20th century, including the impact of science and technology applied to ancient documents and texts. This session will be in the form of an open workshop starting with three short papers (each focusing on a segment of the period of time under consideration, Antiquity, Byzantium, Post-Byzantine period) aiming at generating a discussion. It is expected that the report of the discussion will lead to the publication of a paper surveying the historiography of Greek science during the 20th century. Title: Acid Rain Acid Science Acid Debates Abstract: The debate about the nature and effect of airborne acid rain became a formative environmental debate in the 1970s, particularly in North America and northern Europe. Based on the scientific, political, and social views of the observers, which rationality and whose knowledge one should trust in determining facts became an issue. The papers in this session discuss why scientists from different countries and socio-political backgrounds came to different conclusions about the extent of acidification. -

Daily 40 No. – 8 Joseph Priestly

Daily 40 no. – 8 Joseph Priestly Daily 40 Hall of Fame! Congratulations to these writers! British philosopher Joseph Priestly was known for his contributions towards science through his discovery of oxygen and other gases, invention of soda water, and numerous writings on electricity and theories. Priestly supported the idea of phlogiston, a fire like element, and disagreed with the ideas posed by chemist Antoine Lavoisier. --Tokunbo Joseph Priestley(1733–1804) was a British chemist. He was a believer of phlogiston theory, which supports the existence of phlogiston, an element contained in combustible materials, that is supposedly released during combustion. Priestley invented soda water(seltzer), isolated oxygen gas, and perfected the pneumatic trough, an apparatus used to collect gases. --Jaya Living from 1733-1804 in England, Joseph Priestley studied gases such as carbon monoxide. He improved the pneumatic trough, an apparatus designed to trap gases. For an experiment, Priestley heated mercuric oxide and isolated the oxygen released. However, he mistook oxygen for dephlogisticated air, because he observed that it supported combustion. --Christine Joseph Priestly was born in 1733 in Britain and died in 1804. He is mainly credited for having discovered several “airs,” most notably “dephlogisticated air” or oxygen and was the first to isolate it in its gaseous state. He also invented soda water and wrote about electricity. --Alanna Joseph Priestly, born 1733, was a minister turned scientist. In his chemical reactions, he collected gases from his flask by sealing and connecting it to an inverted bottle of liquid. With this method, he isolated gaseous oxygen, which he called "dephlogisticated air," or air without phlogiston. -

Soho Depicted: Prints, Drawings and Watercolours of Matthew Boulton, His Manufactory and Estate, 1760-1809

SOHO DEPICTED: PRINTS, DRAWINGS AND WATERCOLOURS OF MATTHEW BOULTON, HIS MANUFACTORY AND ESTATE, 1760-1809 by VALERIE ANN LOGGIE A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History of Art College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham January 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis explores the ways in which the industrialist Matthew Boulton (1728-1809) used images of his manufactory and of himself to help develop what would now be considered a ‘brand’. The argument draws heavily on archival research into the commissioning process, authorship and reception of these depictions. Such information is rarely available when studying prints and allows consideration of these images in a new light but also contributes to a wider debate on British eighteenth-century print culture. The first chapter argues that Boulton used images to convey messages about the output of his businesses, to draw together a diverse range of products and associate them with one site. Chapter two explores the setting of the manufactory and the surrounding estate, outlining Boulton’s motivation for creating the parkland and considering the ways in which it was depicted. -

John Dalton By: Period 8 Early Years and Education

John Dalton By: Period 8 Early Years and Education • John Dalton was born in the small British village of Eaglesfield, Cumberland, England to a Quaker family. • As a child, John did not have much formal education because his family was rather poor; however, he did acquire a basic foundation in reading, writing, and arithmetic at a nearby Quaker school. • A teacher by the name of John Fletcher took young John Dalton under his wing and introduced him to a great mentor, Elihu Robinson, who was a rich Quaker. • Elihu then agreed to tutor John in mathematics, science, and meteorology. Shortly after he ended his tutoring sessions with Elihu, Dalton began keeping a daily log of the weather and other matters of meteorology. Education continued • His studies of these weather conditions led him to develop theories and hypotheses about mixed gases and water vapor. • He kept this journal of weather recordings his entire life, which later aided him in his observations and recordings of atoms and elements. Accomplishments • In 1794, Dalton became the first • Dalton joined the Manchester to explain color blindness, Literary and Philosophical which he was afflicted with Society and instantly published himself, at one of his public his first book on Meteorological lectures and it is even Observations and Essays. sometimes called Daltonism referring to John Dalton • In this book, John tells of his himself. ideas on gasses and that “in a • The first paper he wrote on this mixture of gasses, each gas matter was entitled exists independently of each Extraordinary facts relating to other gas and acts accordingly,” the visions of colors “in which which was when he’s famous he postulated that shortage in ideas on the Atomic Theory color perception was caused by started to form. -

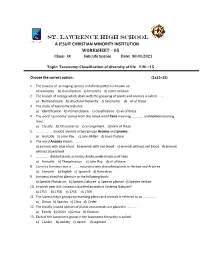

ST. LAWRENCE HIGH SCHOOL a JESUIT CHRISTIAN MINORITY INSTITUTION WORKSHEET – 05 Class: IX Sub: Life Science Date: 30.01.2021

ST. LAWRENCE HIGH SCHOOL A JESUIT CHRISTIAN MINORITY INSTITUTION WORKSHEET – 05 Class: IX Sub: Life Science Date: 30.01.2021 Topic: Taxonomy-Classification of diversity of life F.M. : 15 Choose the correct option: (1x15=15) 1. The process of arranging species in definite pattern is known as: a) taxonomy b) classification c) hierarchy d) nomenclature 2. The branch of biology which deals with the grouping of plants and animals is called …….. a) Nomenclature b) structural hierarchy c) taxonomy d) all of these 3. The study of taxonomy includes: a) Identification b) nomenclature c) classification d) all of these 4. The word ‘taxonomy’ comes from the Greek word Taxis meaning ………….. and nomos meaning laws: a) Classify b) Characterize c) arrangement d)none of these 5. ……………….. divided animals in two groups Anaima and Enaima . a) Aristotle b) John Ray c) John Miller d) Louis Pasteur 6. The word Anaima means …...... a) animals with blue blood b) animals with red blood c) animals without red blood d) animals without blue blood 7. ……………. divided plants as herbs,shrubs,undershrubs and trees. a) Aristotle b) Theophrastus c) John Ray d) all of these 8. Carrolus Linnaeus was a ……… naturalist who classisfied plants in Herbae and Arborea. a) Swedish b) English c) Spainish d) Australian 9. Linnaeus classified plants in in the following book: a) Species Plantarum b) Species Naturae c) Species plantae d) Species herbae 10. In which year did Linnaeus classified animals in Systema Naturae? a) 1753 b) 1758 c) 1756 d) 1769 11. The lowest major group representing plants and animals is referred to as …………… a) Genus b) Species c) Class d) Order 12. -

Section 1 – Oxygen: the Gas That Changed Everything

MYSTERY OF MATTER: SEARCH FOR THE ELEMENTS 1. Oxygen: The Gas that Changed Everything CHAPTER 1: What is the World Made Of? Alignment with the NRC’s National Science Education Standards B: Physical Science Structure and Properties of Matter: An element is composed of a single type of atom. G: History and Nature of Science Nature of Scientific Knowledge Because all scientific ideas depend on experimental and observational confirmation, all scientific knowledge is, in principle, subject to change as new evidence becomes available. … In situations where information is still fragmentary, it is normal for scientific ideas to be incomplete, but this is also where the opportunity for making advances may be greatest. Alignment with the Next Generation Science Standards Science and Engineering Practices 1. Asking Questions and Defining Problems Ask questions that arise from examining models or a theory, to clarify and/or seek additional information and relationships. Re-enactment: In a dank alchemist's laboratory, a white-bearded man works amidst a clutter of Notes from the Field: vessels, bellows and furnaces. I used this section of the program to introduce my students to the concept of atoms. It’s a NARR: One night in 1669, a German alchemist named Hennig Brandt was searching, as he did more concrete way to get into the atomic every night, for a way to make gold. theory. Brandt lifts a flask of yellow liquid and inspects it. Notes from the Field: Humor is a great way to engage my students. NARR: For some time, Brandt had focused his research on urine. He was certain the Even though they might find a scientist "golden stream" held the key. -

Ministers of ‘The Black Art’: the Engagement of British Clergy with Photography, 1839-1914

Ministers of ‘the Black Art’: the engagement of British clergy with photography, 1839-1914 Submitted by James Downs to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in March 2018 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signature: ………………………………………………………….. Abstract 1 Ministers of ‘the Black Art’: the engagement of British clergy with photography, 1839- 1914 This thesis examines the work of ordained clergymen, of all denominations, who were active photographers between 1839 and the beginning of World War One: its primary aim is to investigate the extent to which a relationship existed between the religious culture of the individual clergyman and the nature of his photographic activities. Ministers of ‘the Black Art’ makes a significant intervention in the study of the history of photography by addressing a major weakness in existing work. Taking an interdisciplinary approach, the research draws on a wide range of primary and secondary sources such as printed books, sermons, religious pamphlets, parish and missionary newsletters, manuscript diaries, correspondence, notebooks, biographies and works of church history, as well as visual materials including original glass plate negatives, paper prints and lantern slides held in archival collections, postcards, camera catalogues, photographic ephemera and photographically-illustrated books.