Textiles, Religion and Medicines: William Wilson, a Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 2 Fundamental Questions: Linneaus and Kirchner

2/1/2011 The 2 fundamental questions: y Has evolution taken pp,lace, and if so, what is the Section 4 evidence? Professor Donald McFarlane y If evolution has taken place, what is the mechanism by which it works? Lecture 2 Evolutionary Ideas Evidence for evolution before Darwin Golden Age of Exploration y Magellan’s voyage –1519 y John Ray –University of y Antonius von Leeuwenhoek ‐ microbes –1683 Cambridge (England) y “Catalog of Cambridge Plants” – 1660 –lists 626 species y 1686 –John Ray listing thousands of plant species! y In 1678, Francis Willoughby publishes “Ornithology” Linneaus and Kirchner Athenasius Kircher ~ 1675 –Noah’s ark Carl Linneaus – Sistema Naturae ‐ 1735 Ark too small!! Uses a ‘phenetic” classification – implies a phylogenetic relationship! 300 x 50 x 30 cubits ~ 135 x 20 x 13 m 1 2/1/2011 y Georges Cuvier 1769‐ 1832 y “Fixity of Species” Evidence for Evolution –prior to 1830 • Enormous diversity of life –WHY ??? JBS Haldane " The Creator, if He exists, has "an inordinate fondness for beetles" ". Evidence for Evolution –prior to 1830 Evidence for Evolution –prior to 1830 y The discovery of variation. y Comparative Anatomy. Pentadactyl limbs Evidence for Evolution –prior to Evidence for Evolution –prior to 1830 1830 y Fossils – homologies with living species y Vestigal structures Pentadactyl limbs !! 2 2/1/2011 Evidence for Evolution –prior to 1830 Evidence for Evolution –prior to 1830 y Invariance of the fossil sequence y Plant and animal breeding JBS Haldane: “I will give up my belief in evolution if someone finds a fossil rabbit in the Precambrian.” Charles Darwin Jean Baptiste Lamark y 1744‐1829 y 1809 –1882 y Organisms have the ability to adapt to their y Voyage of Beagle 1831 ‐ 1836 environments over the course of their lives. -

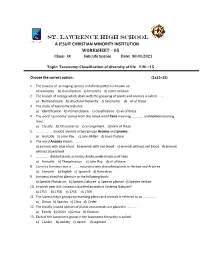

ST. LAWRENCE HIGH SCHOOL a JESUIT CHRISTIAN MINORITY INSTITUTION WORKSHEET – 05 Class: IX Sub: Life Science Date: 30.01.2021

ST. LAWRENCE HIGH SCHOOL A JESUIT CHRISTIAN MINORITY INSTITUTION WORKSHEET – 05 Class: IX Sub: Life Science Date: 30.01.2021 Topic: Taxonomy-Classification of diversity of life F.M. : 15 Choose the correct option: (1x15=15) 1. The process of arranging species in definite pattern is known as: a) taxonomy b) classification c) hierarchy d) nomenclature 2. The branch of biology which deals with the grouping of plants and animals is called …….. a) Nomenclature b) structural hierarchy c) taxonomy d) all of these 3. The study of taxonomy includes: a) Identification b) nomenclature c) classification d) all of these 4. The word ‘taxonomy’ comes from the Greek word Taxis meaning ………….. and nomos meaning laws: a) Classify b) Characterize c) arrangement d)none of these 5. ……………….. divided animals in two groups Anaima and Enaima . a) Aristotle b) John Ray c) John Miller d) Louis Pasteur 6. The word Anaima means …...... a) animals with blue blood b) animals with red blood c) animals without red blood d) animals without blue blood 7. ……………. divided plants as herbs,shrubs,undershrubs and trees. a) Aristotle b) Theophrastus c) John Ray d) all of these 8. Carrolus Linnaeus was a ……… naturalist who classisfied plants in Herbae and Arborea. a) Swedish b) English c) Spainish d) Australian 9. Linnaeus classified plants in in the following book: a) Species Plantarum b) Species Naturae c) Species plantae d) Species herbae 10. In which year did Linnaeus classified animals in Systema Naturae? a) 1753 b) 1758 c) 1756 d) 1769 11. The lowest major group representing plants and animals is referred to as …………… a) Genus b) Species c) Class d) Order 12. -

Australasian Lichenology Australasian Lichenology Number 45, July 1999 Number 45, July 1999

Australasian Lichenology Australasian Lichenology Number 45, July 1999 Number 45, July 1999 Byssoloma sublmdulatllm lmm Byssoloma subdiscordans lmm ANNOUNCEMENTS Dampier 300, Biodiversity in Australia, Perth, 1999 .................................. ....... 2 14th meeting of Australasian lichenologists, Melbourne, 1999 ......................... 2 4th IAL Symposium, Barcelona, 2000 ..... .. .......................................................... 2 The Southern Connection, Christchurch, 2000 .. ............................ ..................... 3 ADDITIONAL LICHEN RECORDS FROM AUSTRALIA Archer, AW (40}-Pertusaria knightiana MUll. Arg........................................... 4 Elix, JA; Streimann, H (41}-Parmeliaceae. .................................... .. ................ 5 ADDITIONAL LICHEN RECORDS FROM NEW ZEALAND Galloway, DJ; Knight, A; Johnson, PN; Hayward, BW (30)-Polycoccum galli genum .. ............................................................................................................... 8 ARTICLES Lumbsch, HT-Notes on some genera erroneously reported for Australia ........ 10 Elix, JA; McCaffery, LF-Three new tridepsides in the lichenPseudocyphellaria billardierei ................................................................................ .. ................ ..... 12 Trinkaus, U; Mayrhofer, H; Matzer, M-Rinodinagennarii (Physciaceae), a wide spread species in the temperate regions of the Southern Hemisphere ........ 15 Malcolm, WM; Vezda, A; McCarthy, PM; Kantvilas, G-Porina subapplanata, a new species from -

The Cultural Circulation of Political Economy, Botany, and Natural Knowledge

social sciences $€ £ ¥ Article Malthus and the Philanthropists, 1764–1859: The Cultural Circulation of Political Economy, Botany, and Natural Knowledge J. Marc MacDonald Department of History, University of Prince Edward Island, 550 University Avenue, Charlottetown, PE C1A 4P3, Canada; [email protected]; Tel.: +1-902-569-4865 Academic Editor: Bryan L. Sykes Received: 16 July 2016; Accepted: 3 January 2017; Published: 10 January 2017 Abstract: Modernity does not possess a monopoly on mass incarceration, population fears, forced migration, famine, or climatic change. Indeed, contemporary and early modern concerns over these matters have extended interests in Thomas Malthus. Yet, despite extensive research on population issues, little work explicates the genesis of population knowledge production or how the process of intellectual transfer occurred during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. This paper examines the Delessert network’s instrumental role in cultivating, curating, and circulating knowledge that popularized Malthusian population theory, including the theory’s constitutive elements of political economy, philanthropy, industry, agriculture, and botany. I show how deviant, nonconformist groups suffered forced migration for their political philosophy, particularly during the revolutionary 1790s, resulting in their imprisonment and migration to America. A consequence of these social shifts was the diffusion and dissemination of population theory—as a pursuit of scientific knowledge and exploration—across both sides of the Atlantic. By focusing on the Delesserts and their social network, I find that a byproduct of inter and intra continental migration among European elites was a knowledge exchange that stimulated Malthus’s thesis on population and Genevan Augustin Pyramus Candolle’s research on botany, ultimately culminating in Charles Darwin’s theory of natural selection and human evolution. -

Professor Robert Scott (Ca

Glasra 3: 115–143 (1998) ‘A willing Cicerone’: Professor Robert Scott (ca. 1757–1808) of Trinity College, Dublin, Fermanagh’s first botanist E. CHARLES NELSON Tippitiwitchet Cottage, Hall Road, Outwell, Wisbech, PE14 8PE, U.K. INTRODUCTION Having been brought up in the lakeland of County Fermanagh, it is hardly surprising that Robert Scott1 (Figure 1) loved outdoors pursuits, fishing for trout, fowling, and geological or botanical rambles looking for minerals, or mosses, lichens and fungi, those inconspicuous but ubiquitous plants that are so often ignored. He was an ‘ingenious, lively man with great merit, and a good botanist’2 and to him Dawson Turner, a Norfolk banker who was also an antiquarian and an eminent botanist, dedicated Muscologiae Hibernicae spicilegium (Figures 2a & b), published privately in Yarmouth in the early Spring 1804. Only the scantiest fragments of information have been published about Scott, who was Professor of Botany in the University of Dublin from late November 1800 until his death in September 1808. Praeger3 recounted his professorship (but gave incorrect dates4) and noted that Scott had discovered intermediate bladderwort, Utricularia intermedia, in Fermanagh5 and the moss Dicranum scottianum in Cavan, that Muscologiae Hibernicae spicilegium was dedicated to him by his ‘chief friend’, Dawson Turner, and that Robert Brown coined Scottia for an Australian genus in the Fabaceae in his memory. Scott received brief mentions in Smith’s English botany,6 Moore’s synopsis of the mosses of Ireland,7 and in the historical preface to Colgan’s Flora of the county Dublin8 where he is credited with adding upright brome, Bromus (= Bromopsis) erectus, to the county’s flora, as well as horned pondweed, Zannichellia palustris, beaked tasselweed, Ruppia maritima, and greater pond-sedge, Carex riparia. -

Ministers of ‘The Black Art’: the Engagement of British Clergy with Photography, 1839-1914

Ministers of ‘the Black Art’: the engagement of British clergy with photography, 1839-1914 Submitted by James Downs to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in March 2018 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signature: ………………………………………………………….. Abstract 1 Ministers of ‘the Black Art’: the engagement of British clergy with photography, 1839- 1914 This thesis examines the work of ordained clergymen, of all denominations, who were active photographers between 1839 and the beginning of World War One: its primary aim is to investigate the extent to which a relationship existed between the religious culture of the individual clergyman and the nature of his photographic activities. Ministers of ‘the Black Art’ makes a significant intervention in the study of the history of photography by addressing a major weakness in existing work. Taking an interdisciplinary approach, the research draws on a wide range of primary and secondary sources such as printed books, sermons, religious pamphlets, parish and missionary newsletters, manuscript diaries, correspondence, notebooks, biographies and works of church history, as well as visual materials including original glass plate negatives, paper prints and lantern slides held in archival collections, postcards, camera catalogues, photographic ephemera and photographically-illustrated books. -

The Linnean NEWSLETTER and PROCEEDINGS of the LINNEAN SOCIETY of LONDON

The Linnean NEWSLETTER AND PROCEEDINGS OF THE LINNEAN SOCIETY OF LONDON Volume 36 Number 1 April 2020 Gangetic Fishes: Parallel History: A British Discovery: Francis Hamilton's Gesellscha� Naturforschender William Bingley FLS commissioned images Freunde zu Berlin AND MORE... Communicating nature since 1788 The Linnean Society of London Burlington House, Piccadilly, London W1J 0BF UK Toynbee House, 92–94 Toynbee Road, Wimbledon SW20 8SL UK (by appointment only) +44 (0)20 7434 4479 www.linnean.org [email protected] @LinneanSociety President SECRETARIES COUNCIL Dr Sandra Knapp Scienti fi c The Offi cers () Vice Presidents Vice Presidents Prof. Simon Hiscock Dr Malcolm Scoble Dr Colin Clubbe Dr Olwen Grace Mathew Frith Dr Blanca Huertas Editorial Prof. Beverley Glover Prof. Paul Henderson Prof. Mark Chase FRS Prof. Anjali Goswami Dr Malcolm Scoble Prof. Alistair Hetherington Collecti ons Prof. Alan Hildrew Treasurer Prof. Dame Georgina Mace FRS Dr Mark Watson Dr John David Dr Silvia Pressel Strategy Prof. Max Telford Dr Natasha de Vere Prof. David Cutler Stephanie West THE TEAM Execu� ve Secretary Financial Controller & Conservator Dr Elizabeth Rollinson Membership Offi cer Janet Ashdown Priya Nithianandan Head of Collec� ons Special Publica� ons Manager Dr Isabelle Charman� er Buildings & Offi ce Manager Leonie Berwick Librarian Helen Shaw Educa� on & Public Engagement Will Beharrell Communica� ons & Events Manager Joe Burton Archivist Manager (To be announced) Mul� media Content Producer c Ross Ziegelmeier Liz M Gow Room Hire & Membership Assistant Archivist Assistant Ta� ana Franco BioMedia Meltdown Project Luke Thorne Offi cer Daryl Stenvoll-Wells Digital Assets Manager Archivist emerita Andrea Deneau Engagement Research & Gina Douglas Delivery Offi cer Zia Forrai Editor Publishing in The Linnean Gina Douglas The Linnean is published twice a year, in April and October. -

The Flower Chain the Early Discovery of Australian Plants

The Flower Chain The early discovery of Australian plants Hamilton and Brandon, Jill Douglas Hamilton Duchess of University of Sydney Library Sydney, Australia 2002 http://setis.library.usyd.edu.au/ozlit © University of Sydney Library. The texts and images are not to be used for commercial purposes without permission Source Text: Prepared with the author's permission from the print edition published by Kangaroo Press Sydney 1998 All quotation marks are retained as data. First Published: 1990 580.994 1 Australian Etext Collections at botany prose nonfiction 1940- women writers The flower chain the early discovery of Australian plants Sydney Kangaroo Press 1998 Preface Viewing Australia through the early European discovery, naming and appreciation of its flora, gives a fresh perspective on the first white people who went to the continent. There have been books on the battle to transform the wilderness into an agriculturally ordered land, on the convicts, on the goldrush, on the discovery of the wealth of the continent, on most aspects of settlement, but this is the first to link the story of the discovery of the continent with the slow awareness of its unique trees, shrubs and flowers of Australia. The Flower Chain Chapter 1 The Flower Chain Begins Convict chains are associated with early British settlement of Australia, but there were also lighter chains in those grim days. Chains of flowers and seeds to be grown and classified stretched across the oceans from Botany Bay to Europe, looping back again with plants and seeds of the old world that were to Europeanise the landscape and transform it forever. -

The Charles Knight-Joseph Hooker Correspondence

A man tenax propositi: transcriptions of letters from Charles Knight to William Jackson Hooker and Joseph Dalton Hooker between 1852 and 1883 David J. Galloway Hon. Research Associate Landcare Research, and Te Papa Tongarewa [email protected] Geoscience Society of New Zealand miscellaneous publication 133J December 2013 Published by the Geoscience Society of New Zealand Inc, 2013 Information on the Society and its publications is given at www.gsnz.org.nz © Copyright David J. Galloway, 2013 Geoscience Society of New Zealand miscellaneous publication 133J ISBN 978-1-877480-36-2 ISSN 2230-4495 (Online) ISSN 2230-4487 (Print) This document is available as a PDF file that can be downloaded from the Geoscience Society website at: http://www.gsnz.org.nz/information/misc-series-i-49.html Bibliographic Reference Galloway D.J. 2013: A man tenax propositi: transcriptions of letters from Charles Knight to William Jackson Hooker and Joseph Dalton Hooker between 1852 and 1883 Geoscience Society of New Zealand miscellaneous publication 133J. 88 pages. A man tenax propositi: transcriptions of letters from Charles Knight to William Jackson Hooker and Joseph Dalton Hooker between 1852 and 1883 Contents Introduction 3 Charles Knight correspondence at Kew 5 Acknowledgements 6 Summaries of the letters 7 Transcriptions of the letters from Charles Knight 15 Footnotes 70 References 77 Figure 1: Dr Charles Knight FLS, FRCS 2 Figure 2: Group photograph including Charles Knight 2 Figure 3: Page of letter from Knight to Hooker 14 Table 1: Comparative chronology of Charles Knight, W.J. Hooker and J.D. Hooker 86 1 Figure 1: Dr Charles Knight FLS, FRCS Alexander Turnbull Library,Wellington, New Zealand ¼-015414 Figure 2: Group taken in Walter Mantell‟s garden about 1865 showing Charles Knight (left), John Buchanan and James Hector (right) and Walter Mantell and his young son, Walter Godfrey Mantell (seated on grass). -

Irish Spurge (Euphorbia Hyberna) in England: Native Or Naturalised?

British & Irish Botany 1(3): 243-249, 2019 Irish Spurge (Euphorbia hyberna) in England: native or naturalised? John Lucey* Kilkenny, Ireland *Corresponding author: John Lucey, email: [email protected] This pdf constitutes the Version of Record published on 13th August 2019 Abstract Most modern authorities have considered Euphorbia hyberna to be native in Britain but with the possibility that it could have been introduced from Ireland. The results from a literature survey, on the historical occurrence of the species, strongly suggest that it was introduced and has become naturalised at a few locations in south-west England. Keywords: status; Cornwall; Devon; Lusitanian; horticulture Introduction The Irish Spurge (Euphorbia hyberna L.) is an extremely rare plant in England with only recent occurrences for west Cornwall, north Devon and south Somerset (Stace, 2010) although now extinct in the last vice-county (Crouch, 2014). The earliest records for the three vice-counties contained in the Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland (BSBI) Database (DDb) are: 1842 v.c.4 Lynton (Ward, N.B. More, W.S.) 1883 vc.1 Portreath (Marquand, E.D.) 1898 v.c.5 Badgworthy Valley (Salmon, C.E.) As the only element of the so-called Lusitanian flora in England, with an extremely restricted distribution pattern in the south-west, the species represents an unresolved biogeographical conundrum: native or naturalised? A review of the historical literature can provide valuable information on a species’ occurrence and thus may help in determining if it may have been introduced to a region. Botanical and other literature sources on the historical occurrence of E. -

History of Taxonomy

History of Taxonomy The history of taxonomy dates back to the origin of human language. Western scientific taxonomy started in Greek some hundred years BC and are here divided into prelinnaean and postlinnaean. The most important works are cited and the progress of taxonomy (with the focus on botanical taxonomy) are described up to the era of the Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus, who founded modern taxonomy. The development after Linnaeus is characterized by a taxonomy that increasingly have come to reflect the paradigm of evolution. The used characters have extended from morphological to molecular. Nomenclatural rules have developed strongly during the 19th and 20th century, and during the last decade traditional nomenclature has been challenged by advocates of the Phylocode. Mariette Manktelow Dept of Systematic Biology Evolutionary Biology Centre Uppsala University Norbyv. 18D SE-752 36 Uppsala E-mail: [email protected] 1. Pre-Linnaean taxonomy 1.1. Earliest taxonomy Taxonomy is as old as the language skill of mankind. It has always been essential to know the names of edible as well as poisonous plants in order to communicate acquired experiences to other members of the family and the tribe. Since my profession is that of a systematic botanist, I will focus my lecture on botanical taxonomy. A taxonomist should be aware of that apart from scientific taxonomy there is and has always been folk taxonomy, which is of great importance in, for example, ethnobiological studies. When we speak about ancient taxonomy we usually mean the history in the Western world, starting with Romans and Greek. However, the earliest traces are not from the West, but from the East. -

Middleton and John Ray Jo Walker from Middleton Hall on the Story Behind an Historic and Rare Rose

Middleton and John Ray Jo Walker from Middleton Hall on the story behind an historic and rare rose Middleton Hall is a Grade ‘Historia Piscium’ were II* listed manor with a published after his death by John Ray. John Ray tutored museum housed in Francis’ children whilst he buildings spanning 750 stayed at Middleton Hall and years of architectural remained at the Hall for a Rose “John Ray” is believed to survive styles. The surrounding number of years after Francis’ only in Middleton Hall’s walled garden estate covers 42 acres and death. It was at Middleton that he developed his original works includes a Site of Special on Natural History including his was gradually superseded by the Scientific Interest, a walled ‘History of Plants’. garden and shops. Now Linnean method which was first John Ray (1627-1705) applied to English botany in Dr J. restored the Hall is run by Philosopher and writer, cleric, Hill’s Flora Britannica 1760. a small independent traveller and taxonomist, Ray enjoyed the advantage of a charitable trust. Middleton deserves a wider reputation. His very long period of productive botanical works - ‘Historiae Hall has had a wide variety activity: in the thirty-four years Plantum’ and ‘Methodus of owners and tenants. that separated his Tables of Plantarum Nova’, were published Plants from his Methodus Two of our most famous 1682. Emendata et Aucta, he had time residents were the great Known as the father of English to revise and remodel his naturalists Francis Willughby natural history, John Ray’s system. (who spelt his name this way) system of plant classification and his tutor, friend and During his residence in became more popular than that collaborator John Ray.