Engraving the Herball: Frontispieces and the Visual Understanding of Botany in 16Th – 17Th Century England

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

English Roots

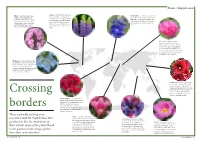

Plants / English roots Lupin – cultivated for thousands of Phlox – arrived in Europe from Delphinium – modern day varieties are years, originally as a fodder plant, Virginia, North America in the the result of interbreeding of species from as far apart as ancient Egypt and the early 18th century before crossing many parts of the world, from the Swiss Peruvian Andes. The tall colourful the channel a century later. Many Alps to Siberia. They have been a part of spires popular in English gardens varieties have been bred since not the English garden since at least Tudor have their origin in North American only in England but also in the times. species that arrived in Britain in the Netherlands and United States. 1820s. Rose – the English rose is the result of centuries of breeding of many varieties of rose from around world. One of these is the Damask rose, named after the Syrian city of Damascus, famous for its fragrance. It is thought to have first been brought to England by the Crusaders. Hydrangea – first introduced from Pennsylvania, North America in 1736. In the nineteenth century they became a favourite of plant hunters and botanists, including the famous Joseph Banks who brought more varieties back from China and Japan. Hollyhock – possible origins range from and Syria to India but mostly likely to be natives of China. This statuesque plant worked its way along the Silk Road over many centuries and is first mentioned in English Crossing literature in John Gardiners poem ’Feate of Gardenini’ in 1440. Sweet William – first appeared in English botanist John Gerard’s garden catalogue in 1596 having made their way from mountainous regions of southern Europe, such as the borders Pyrenees and the Carpathians. -

The 2 Fundamental Questions: Linneaus and Kirchner

2/1/2011 The 2 fundamental questions: y Has evolution taken pp,lace, and if so, what is the Section 4 evidence? Professor Donald McFarlane y If evolution has taken place, what is the mechanism by which it works? Lecture 2 Evolutionary Ideas Evidence for evolution before Darwin Golden Age of Exploration y Magellan’s voyage –1519 y John Ray –University of y Antonius von Leeuwenhoek ‐ microbes –1683 Cambridge (England) y “Catalog of Cambridge Plants” – 1660 –lists 626 species y 1686 –John Ray listing thousands of plant species! y In 1678, Francis Willoughby publishes “Ornithology” Linneaus and Kirchner Athenasius Kircher ~ 1675 –Noah’s ark Carl Linneaus – Sistema Naturae ‐ 1735 Ark too small!! Uses a ‘phenetic” classification – implies a phylogenetic relationship! 300 x 50 x 30 cubits ~ 135 x 20 x 13 m 1 2/1/2011 y Georges Cuvier 1769‐ 1832 y “Fixity of Species” Evidence for Evolution –prior to 1830 • Enormous diversity of life –WHY ??? JBS Haldane " The Creator, if He exists, has "an inordinate fondness for beetles" ". Evidence for Evolution –prior to 1830 Evidence for Evolution –prior to 1830 y The discovery of variation. y Comparative Anatomy. Pentadactyl limbs Evidence for Evolution –prior to Evidence for Evolution –prior to 1830 1830 y Fossils – homologies with living species y Vestigal structures Pentadactyl limbs !! 2 2/1/2011 Evidence for Evolution –prior to 1830 Evidence for Evolution –prior to 1830 y Invariance of the fossil sequence y Plant and animal breeding JBS Haldane: “I will give up my belief in evolution if someone finds a fossil rabbit in the Precambrian.” Charles Darwin Jean Baptiste Lamark y 1744‐1829 y 1809 –1882 y Organisms have the ability to adapt to their y Voyage of Beagle 1831 ‐ 1836 environments over the course of their lives. -

Medical Appropriation in the 'Red' Atlantic: Translating a Mi'kmaq

1 Medical Appropriation in the ‘Red’ Atlantic: Translating a Mi’kmaq smallpox cure in the mid-nineteenth century Farrah Lawrence-Mackey University College London Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History and Philosophy of Science Department of Science and Technology Studies 2018 2 I, Farrah Mary Lawrence-Mackey confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 3 ABSTRACT This thesis answers the questions of what was travelling, how, and why, when a Kanien’kehaka woman living amongst the Mi’kmaq at Shubenacadie sold a remedy for smallpox to British and Haligonian colonisers in 1861. I trace the movement of the plant (known as: Mqo’oqewi’k, Indian Remedy, Sarracenia purpurea, and Limonio congener) and knowledges of its use from Britain back across the Atlantic. In exploring how this remedy travelled, why at this time and what contexts were included with the plant’s removal I show that rising scientific racism in the nineteenth century did not mean that Indigenous medical flora and knowledge were dismissed wholesale, as scholars like Londa Schiebinger have suggested. Instead conceptions of indigeneity were fluid, often lending authority to appropriated flora and knowledge while the contexts of nineteenth-century Britain, Halifax and Shubenacadie created the Sarracenia purpurea, Indian Remedy and Mqo’oqewi’k as it moved through and between these spaces. Traditional accounts of bio-prospecting argue that as Indigenous flora moved, Indigenous contexts were consistently stripped away. This process of stripping shapes Indigenous origins as essentialised and static. -

Gerard's Herbal the OED Defines the Word

Gerard’s Herbal The OED defines the word ‘herbal’ (n) as: ‘a book containing the names and descriptions of herbs, or of plants in general, with their properties and virtues; a treatise in plants.’ Charles Singer, historian of medicine and science, describes herbals as ‘a collection of descriptions of plants usually put together for medical purposes. The term is perhaps now-a-days used most frequently in connection with the finely illustrated works produced by the “fathers of botany” in the fifteenth and sixteenth century.’1 Although the origin of the herbal dates back to ‘remote antiquity’2 the advent of the printing press meant that herbals could be produced in large quantities (in comparison to their earlier manuscript counterparts) with detailed woodcut and metal engraving illustrations. The first herbal printed in Britain was Richard Banckes' Herball of 15253, which was written in plain text. Following Banckes, herbalists such as William Turner and John Gerard gained popularity with their lavishly illustrated herbals. Gerard’s Herbal was originally published in 1597; it is regarded as being one of the best of the printed herbals and is the first herbal to contain an illustration of a potato4. Gerard did Illustration of Gooseberries from not have an enormously interesting life; he was Gerard’s Herbal (1633), demonstrating the intricate detail that ‘apprenticed to Alexander Mason, a surgeon of 5 characterises this text. the Barber–Surgeons' Company’ and probably ‘travelled in Scandinavia and Russia, as he frequently refers to these places in his writing’6. For all his adult life he lived in a tenement with a garden probably belonging to Lord Burghley. -

The Exotic World of Carolus Clusius 1526-1609 and a Reconstruction of the Clusius Garden

The Netherlandish humanist Carolus Clusius (Arras 1526- Leiden 1609) is one of the most important European the exotic botanists of the sixteenth century. He is the author of innovative, internationally famous botanical publications, the exotic worldof he introduced exotic plants such as the tulip and potato world of in the Low Countries, and he was advisor of princes and aristocrats in various European countries, professor and director of the Hortus botanicus in Leiden, and central figure in a vast European network of exchanges. Carolus On 4 April 2009 Leiden University, Leiden University Library, The Hortus botanicus and the Scaliger Institute 1526-1609 commemorate the quatercentenary of Clusius’ death with an exhibition The Exotic World of Carolus Clusius 1526-1609 and a reconstruction of the Clusius Garden. Clusius carolus clusius scaliger instituut clusius all3.indd 1 16-03-2009 10:38:21 binnenwerk.qxp 16-3-2009 11:11 Pagina 1 Kleine publicaties van de Leidse Universiteitsbibliotheek Nr. 80 binnenwerk.qxp 16-3-2009 11:12 Pagina 2 binnenwerk.qxp 16-3-2009 11:12 Pagina 3 The Exotic World of Carolus Clusius (1526-1609) Catalogue of an exhibition on the quatercentenary of Clusius’ death, 4 April 2009 Edited by Kasper van Ommen With an introductory essay by Florike Egmond LEIDEN UNIVERSITY LIBRARY LEIDEN 2009 binnenwerk.qxp 16-3-2009 11:12 Pagina 4 ISSN 0921-9293, volume 80 This publication was made possible through generous grants from the Clusiusstichting, Clusius Project, Hortus botanicus and The Scaliger Institute, Leiden. Web version: https://disc.leidenuniv.nl/view/exh.jsp?id=exhubl002 Cover: Jacob de Monte (attributed), Portrait of Carolus Clusius at the age of 59. -

Colonial Garden Plants

COLONIAL GARD~J~ PLANTS I Flowers Before 1700 The following plants are listed according to the names most commonly used during the colonial period. The botanical name follows for accurate identification. The common name was listed first because many of the people using these lists will have access to or be familiar with that name rather than the botanical name. The botanical names are according to Bailey’s Hortus Second and The Standard Cyclopedia of Horticulture (3, 4). They are not the botanical names used during the colonial period for many of them have changed drastically. We have been very cautious concerning the interpretation of names to see that accuracy is maintained. By using several references spanning almost two hundred years (1, 3, 32, 35) we were able to interpret accurately the names of certain plants. For example, in the earliest works (32, 35), Lark’s Heel is used for Larkspur, also Delphinium. Then in later works the name Larkspur appears with the former in parenthesis. Similarly, the name "Emanies" appears frequently in the earliest books. Finally, one of them (35) lists the name Anemones as a synonym. Some of the names are amusing: "Issop" for Hyssop, "Pum- pions" for Pumpkins, "Mushmillions" for Muskmellons, "Isquou- terquashes" for Squashes, "Cowslips" for Primroses, "Daffadown dillies" for Daffodils. Other names are confusing. Bachelors Button was the name used for Gomphrena globosa, not for Centaurea cyanis as we use it today. Similarly, in the earliest literature, "Marygold" was used for Calendula. Later we begin to see "Pot Marygold" and "Calen- dula" for Calendula, and "Marygold" is reserved for Marigolds. -

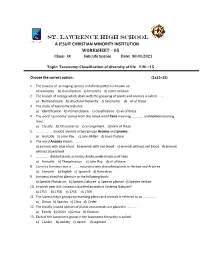

ST. LAWRENCE HIGH SCHOOL a JESUIT CHRISTIAN MINORITY INSTITUTION WORKSHEET – 05 Class: IX Sub: Life Science Date: 30.01.2021

ST. LAWRENCE HIGH SCHOOL A JESUIT CHRISTIAN MINORITY INSTITUTION WORKSHEET – 05 Class: IX Sub: Life Science Date: 30.01.2021 Topic: Taxonomy-Classification of diversity of life F.M. : 15 Choose the correct option: (1x15=15) 1. The process of arranging species in definite pattern is known as: a) taxonomy b) classification c) hierarchy d) nomenclature 2. The branch of biology which deals with the grouping of plants and animals is called …….. a) Nomenclature b) structural hierarchy c) taxonomy d) all of these 3. The study of taxonomy includes: a) Identification b) nomenclature c) classification d) all of these 4. The word ‘taxonomy’ comes from the Greek word Taxis meaning ………….. and nomos meaning laws: a) Classify b) Characterize c) arrangement d)none of these 5. ……………….. divided animals in two groups Anaima and Enaima . a) Aristotle b) John Ray c) John Miller d) Louis Pasteur 6. The word Anaima means …...... a) animals with blue blood b) animals with red blood c) animals without red blood d) animals without blue blood 7. ……………. divided plants as herbs,shrubs,undershrubs and trees. a) Aristotle b) Theophrastus c) John Ray d) all of these 8. Carrolus Linnaeus was a ……… naturalist who classisfied plants in Herbae and Arborea. a) Swedish b) English c) Spainish d) Australian 9. Linnaeus classified plants in in the following book: a) Species Plantarum b) Species Naturae c) Species plantae d) Species herbae 10. In which year did Linnaeus classified animals in Systema Naturae? a) 1753 b) 1758 c) 1756 d) 1769 11. The lowest major group representing plants and animals is referred to as …………… a) Genus b) Species c) Class d) Order 12. -

Maura C. Flannery St

Goethe and the Molecular Aesthetic Maura C. Flannery St. John’s University I argue here that Goethe’s “delicate empiricism” is not an alternative approach to science, but an approach that scientists use consistently, though they usually do not label it as such. I further contend that Goethe’s views are relevant to today’s science, specifically to work on the structure of macromolecules such as proteins. Using the work of Agnes Arber, a botanist and philosopher of science, I will show how her writings help to relate Goethe’s work to present-day issues of cogni- tion and perception. Many observers see Goethe’s “delicate empiricism” as an antidote to reductionism and to the strict separation of the objective and subjective so prevalent in science today. The argument is that there is a different way to do science, Goethe’s way, and it can achieve discoveries which would be impossible with more positivistic approaches. While I agree that Goethe’s method of doing science can be viewed in this light, I would like to take a different approach and use the writings of the plant morphologist Agnes Arber in the process since she worked in the Goethean tradition and en- larged upon it. I argue here that Goethe’s way of science is done by many, if not most scientists, that there is not a strict dichotomy between these two ways of doing science, but rather scientists move between the two approaches so frequently and the shift is so seamless that it is difficult for them to even realize that it is happening. -

HSS Paper 2000

The Many Books of Nature: How Renaissance naturalists created and responded to information overload Brian W. Ogilvie* History of Science Society Annual Meeting, Vancouver, Nov. 3, 2000 Copyright © 2000 Brian W. Ogilvie. All rights reserved. Renaissance natural history emerged in the late fifteenth century at the confluence of humanist textual criticism, the revival of Greek medical texts, and curricular reform in medicine.1 These streams had been set in motion by a deeper tectonic shift: an increasing interest in particular, empirical knowledge among humanists and their pupils, who rejected the scholastic definition of scientific knowledge as certain deductions from universal principles.2 Natural history, which had been seen in antiquity and the Middle Ages as a propaedeutic to natural philosophy or medicine, emerged from this confluence as a distinct discipline with its own set of practitioners, techniques, and norms.3 Ever since Linnaeus, description, nomenclature, and taxonomy have been taken to be the sine qua non of natural history; pre-Linnaean natural history has been treated by many historians as a kind of blind groping toward self-evident principles of binomial nomenclature and encaptic taxa that were first stated clearly by the Swedish naturalist. Today I would like to present a different history. For natural history in the Renaissance, from the late fifteenth through the early seventeenth century, was not a taxonomic * Department of History, Herter Hall, University of Massachusetts, 161 Presidents Drive, Amherst, MA 01003-9312; [email protected]. 2 science. Rather, it was a science of describing, whose goal was a comprehensive catalogue of nature. Botany was at the forefront of that development, for the study of plants had both medical and horticultural applications, but botanists (botanici) rapidly developed interests that went beyond the pharmacy and the garden, to which some scarcely even nodded their heads by 1600. -

Ministers of ‘The Black Art’: the Engagement of British Clergy with Photography, 1839-1914

Ministers of ‘the Black Art’: the engagement of British clergy with photography, 1839-1914 Submitted by James Downs to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in March 2018 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signature: ………………………………………………………….. Abstract 1 Ministers of ‘the Black Art’: the engagement of British clergy with photography, 1839- 1914 This thesis examines the work of ordained clergymen, of all denominations, who were active photographers between 1839 and the beginning of World War One: its primary aim is to investigate the extent to which a relationship existed between the religious culture of the individual clergyman and the nature of his photographic activities. Ministers of ‘the Black Art’ makes a significant intervention in the study of the history of photography by addressing a major weakness in existing work. Taking an interdisciplinary approach, the research draws on a wide range of primary and secondary sources such as printed books, sermons, religious pamphlets, parish and missionary newsletters, manuscript diaries, correspondence, notebooks, biographies and works of church history, as well as visual materials including original glass plate negatives, paper prints and lantern slides held in archival collections, postcards, camera catalogues, photographic ephemera and photographically-illustrated books. -

Continuity and Transformation in the World Polity: Toward a Neorealist Synthesis Reviewed Work(S): Theory of International Politics

Review: Continuity and Transformation in the World Polity: Toward a Neorealist Synthesis Reviewed Work(s): Theory of International Politics. by Kenneth N. Waltz Review by: John Gerard Ruggie Source: World Politics, Vol. 35, No. 2 (Jan., 1983), pp. 261-285 Published by: Cambridge University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2010273 Accessed: 04-10-2017 18:15 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms Cambridge University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to World Politics This content downloaded from 128.103.193.216 on Wed, 04 Oct 2017 18:15:39 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms CONTINUITY AND TRANSFORMATION IN THE WORLD POLITY: Toward a Neorealist Synthesis By JOHN GERARD RUGGIE* Kenneth N. Waltz, Theory of International Politics. Reading, Mass.: Addison- Wesley Publishing Company, 1979, 251 pp., $7.95 (paper). IN The Rules of Sociological Method, Emile Durkheim sought to es- tablish the "social milieu," or society itself, "as the determining factor of collective evolution." In turn, he took society to reflect not the mere summation of individuals -

“Jogging Along with and Without James Logan: Early Plant Science in Philadelphia”

1 Friday, 19 September 2014, 1:30–3:00 p.m.: Panel II: “Leaves” “Jogging Along With and Without James Logan: Early Plant Science in Philadelphia” Joel T. Fry, Bartram's Garden Presented at the ― James Logan and the Networks of Atlantic Culture and Politics, 1699-1751 conference Philadelphia, PA, 18-20 September 2014 Please do not cite, quote, or circulate without written permission from the author These days, John Bartram (1699-1777) and James Logan (1674-1751) are routinely recognized as significant figures in early American science, and particularly botanic science, even if exactly what they accomplished is not so well known. Logan has been described by Brooke Hindle as “undoubtedly the most distinguished scientist in the area” and “It was in botany that James Logan made his greatest contribution to science.” 1 Raymond Stearns echoed, “Logan’s greatest contribution to science was in botany.”2 John Bartram has been repeatedly crowned as the “greatest natural botanist in the world” by Linnaeus no less, since the early 19th century, although tracing the source for that quote and claim can prove difficult.3 Certainly Logan was a great thinker and scholar, along with his significant political and social career in early Pennsylvania. Was Logan a significant botanist—maybe not? John Bartram too may not have been “the greatest natural botanist in the world,” but he was very definitely a unique genius in his own right, and almost certainly by 1750 Bartram was the best informed scientist in the Anglo-American world on the plants of eastern North America. There was a short period of active scientific collaboration in botany between Bartram and Logan, which lasted at most through the years 1736 to 1738.