Of the Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

English Roots

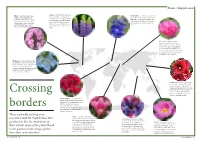

Plants / English roots Lupin – cultivated for thousands of Phlox – arrived in Europe from Delphinium – modern day varieties are years, originally as a fodder plant, Virginia, North America in the the result of interbreeding of species from as far apart as ancient Egypt and the early 18th century before crossing many parts of the world, from the Swiss Peruvian Andes. The tall colourful the channel a century later. Many Alps to Siberia. They have been a part of spires popular in English gardens varieties have been bred since not the English garden since at least Tudor have their origin in North American only in England but also in the times. species that arrived in Britain in the Netherlands and United States. 1820s. Rose – the English rose is the result of centuries of breeding of many varieties of rose from around world. One of these is the Damask rose, named after the Syrian city of Damascus, famous for its fragrance. It is thought to have first been brought to England by the Crusaders. Hydrangea – first introduced from Pennsylvania, North America in 1736. In the nineteenth century they became a favourite of plant hunters and botanists, including the famous Joseph Banks who brought more varieties back from China and Japan. Hollyhock – possible origins range from and Syria to India but mostly likely to be natives of China. This statuesque plant worked its way along the Silk Road over many centuries and is first mentioned in English Crossing literature in John Gardiners poem ’Feate of Gardenini’ in 1440. Sweet William – first appeared in English botanist John Gerard’s garden catalogue in 1596 having made their way from mountainous regions of southern Europe, such as the borders Pyrenees and the Carpathians. -

Invented Herbal Tradition.Pdf

Journal of Ethnopharmacology 247 (2020) 112254 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Ethnopharmacology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jethpharm Inventing a herbal tradition: The complex roots of the current popularity of T Epilobium angustifolium in Eastern Europe Renata Sõukanda, Giulia Mattaliaa, Valeria Kolosovaa,b, Nataliya Stryametsa, Julia Prakofjewaa, Olga Belichenkoa, Natalia Kuznetsovaa,b, Sabrina Minuzzia, Liisi Keedusc, Baiba Prūsed, ∗ Andra Simanovad, Aleksandra Ippolitovae, Raivo Kallef,g, a Ca’ Foscari University of Venice, Via Torino 155, 30172, Mestre, Venice, Italy b Institute for Linguistic Studies, Russian Academy of Sciences, Tuchkov pereulok 9, 199004, St Petersburg, Russia c Tallinn University, Narva rd 25, 10120, Tallinn, Estonia d Institute for Environmental Solutions, "Lidlauks”, Priekuļu parish, LV-4126, Priekuļu county, Latvia e A.M. Gorky Institute of World Literature of the Russian Academy of Sciences, 25a Povarskaya st, 121069, Moscow, Russia f Kuldvillane OÜ, Umbusi village, Põltsamaa parish, Jõgeva county, 48026, Estonia g University of Gastronomic Sciences, Piazza Vittorio Emanuele 9, 12042, Pollenzo, Bra, Cn, Italy ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Ethnopharmacological relevance: Currently various scientific and popular sources provide a wide spectrum of Epilobium angustifolium ethnopharmacological information on many plants, yet the sources of that information, as well as the in- Ancient herbals formation itself, are often not clear, potentially resulting in the erroneous use of plants among lay people or even Eastern Europe in official medicine. Our field studies in seven countries on the Eastern edge of Europe have revealed anunusual source interpretation increase in the medicinal use of Epilobium angustifolium L., especially in Estonia, where the majority of uses were Ethnopharmacology specifically related to “men's problems”. -

Optimization of Agro-Residues As Substrates for Pleurotus

Wu et al. AMB Expr (2019) 9:184 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13568-019-0907-1 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Open Access Optimization of agro-residues as substrates for Pleurotus pulmonarius production Nan Wu1†, Fenghua Tian1†, Odeshnee Moodley1, Bing Song1, Chuanwen Jia1, Jianqiang Ye2, Ruina Lv1, Zhi Qin3 and Changtian Li1* Abstract The “replacing wood by grass” project can partially resolve the confict between mushroom production and balancing the ecosystem, while promoting agricultural economic sustainability. Pleurotus pulmonarius is an economically impor- tant edible and medicinal mushroom, which is traditionally produced using a substrate consisting of sawdust and cottonseed hulls, supplemented with wheat bran. A simplex lattice design was applied to systemically optimize the cultivation of P. pulmonarius using agro-residues as the main substrate to replace sawdust and cottonseed hulls. The efects of difering amounts of wheat straw, corn straw, and soybean straw on the variables of yield, mycelial growth rate, stipe length, pileus length, pileus width, and time to harvest were demonstrated. Results indicated that a mix of wheat straw, corn straw, and soybean straw may have signifcantly positive efects on each of these variables. The high yield comprehensive formula was then optimized to include 40.4% wheat straw, 20.3% corn straw, 18.3% soybean straw, combined with 20.0% wheat bran, and 1.0% light CaCO3 (C/N 42.50). The biological efciency was 15.2% greater than that of the control. Most encouraging was the indication= that the high yield comprehensive formula may shorten the time to reach the reproductive stage by 6 days, compared with the control. -

Wfrs Triennial Report 2015-2018

WFRS TRIENNIAL REPORT 2018 1 WFRS TRIENNIAL REPORT ON ROSES 2018 Published for the World Federation of Rose Societies COMPILED AND EDITED BY Sheenagh Harris WORLD FEDERATION OF ROSE SOCIETIES Founded 1968 www.worldrose.org The World Federation of Rose Societies is registered in Great Britain as a company limited by guarantee and as a charity under the number 1063582. The objectives of the Society, as stated in the constitution, are: To encourage and facilitate the interchange of information about and knowledge of the rose between national rose societies. To co-ordinate the holding of international conventions and exhibitions. To encourage, and where appropriate, sponsor research into problems concerning the rose. To establish common standards for judging new rose seedlings. To assist in coordinating the registration of new rose names. To establish a uniform system of rose classification. To grant international honours and/or awards. To encourage and advance international cooperation in all other matters concerning the rose. 2 CONTENT Foreword 4 Member Country Reports 86 Preface 6 Argentina 86 Editorial 7 Australia 89 President’s Report 8 Austria 92 Immediate Past President’s Report 11 Belgium 93 WFRS Office Holders 2015-2018 12 Bermuda 96 WFRS Standing Committees 14 Canada 98 WFRS Member Country Societies 15 Chile 99 The Breeders’ Club 17 China 101 Friends of the Federation 19 Czech Republic 103 WFRS Vice Presidential Reports Denmark 104 Africa 20 Finland 107 Australasia – Australia 21 France 109 Australasia - New Zealand 22 Germany 111 Central Asia 23 Great Britain 118 Europe (N) 25 Greece 121 Europe (SE) 27 Hungary 122 Europe (S) 29 Iceland 123 Far East 31 India 125 North America - USA 34 Israel 128 North America – Can. -

Botanical Gardens in France

France Total no. of Botanic Gardens recorded in France: 104, plus 10 in French Overseas Territories (French Guiana, Guadeloupe, Martinique and Réunion). Approx. no. of living plant accessions recorded in these botanic gardens: c.300,000 Approx. no. of taxa in these collections: 30,000 to 40,000 (20,000 to 25,000 spp.) Estimated % of pre-CBD collections: 80% to 90% Notes: In 1998 36 botanic gardens in France issued an Index Seminum. Most were sent internationally to between 200 and 1,000 other institutions. Location: ANDUZE Founded: 1850 Garden Name: La Bambouseraie (Maurice Negre Parc Exotique de Prafrance) Address: GENERARGUES, F-30140 ANDUZE Status: Private. Herbarium: Unknown. Ex situ Collections: World renowned collection of more than 100 species and varieties of bamboos grown in a 6 ha plot, including 59 spp.of Phyllostachys. Azaleas. No. of taxa: 260 taxa Rare & Endangered plants: bamboos. Special Conservation Collections: bamboos. Location: ANGERS Founded: 1895 Garden Name: Jardin Botanique de la Faculté de Pharmacie Address: Faculte Mixte de Medecine et Pharmacie, 16 Boulevard Daviers, F-49045 ANGERS. Status: Universiy Herbarium: No Ex situ Collections: Trees and shrubs (315 taxa), plants used for phytotherapy and other useful spp. (175 taxa), systematic plant collection (2,000 taxa), aromatic, perfume and spice plants (22 spp), greenhouse plants (250 spp.). No. of taxa: 2,700 Rare & Endangered plants: Unknown Location: ANGERS Founded: 1863 Garden Name: Arboretum Gaston Allard Address: Service des Espaces Verts de la Ville, Mairie d'Angers, BP 3527, 49035 ANGERS Cedex. Situated: 9, rue du Château d’Orgement 49000 ANGERS Status: Municipal Herbarium: Yes Approx. -

Admirable Trees of Through Two World Wars and Witnessed the Nation’S Greatest Dramas Versailles

Admirable trees estate of versailles estate With Patronage of maison rémy martin The history of France from tree to tree Established in 1724 and granted Royal Approval in 1738 by Louis XV, Trees have so many stories to tell, hidden away in their shadows. At Maison Rémy Martin shares with the Palace of Versailles an absolute Versailles, these stories combine into a veritable epic, considering respect of time, a spirit of openness and innovation, a willingness to that some of its trees have, from the tips of their leafy crowns, seen pass on its exceptional knowledge and respect for the environment the kings of France come and go, observed the Revolution, lived – all of which are values that connect it to the Admirable Trees of through two World Wars and witnessed the nation’s greatest dramas Versailles. and most joyous celebrations. Strolling from tree to tree is like walking through part of the history of France, encompassing the influence of Louis XIV, the experi- ments of Louis XV, the passion for hunting of Louis XVI, as well as the great maritime expeditions and the antics of Marie-Antoinette. It also calls to mind the unending renewal of these fragile giants, which can be toppled by a strong gust and need many years to grow back again. Pedunculate oak, Trianon forecourts; planted during the reign of Louis XIV, in 1668, this oak is the doyen of the trees on the Estate of Versailles 1 2 From the French-style gardens in front of the Palace to the English garden at Trianon, the Estate of Versailles is dotted with extraordi- nary trees. -

TREES Available to Request in the Friends of Metro Parks Commemorative Tree & Bench Program

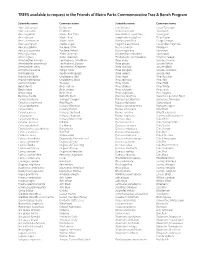

TREES available to request in the Friends of Metro Parks Commemorative Tree & Bench Program Scientific name Common name Scientific name Common name Abies balsamaea Fir, Balsam Larix laricina Larch, Tamarack Abies concolor Fir, White Lindera benzoin Spicebush Acer negundo Maple, Box Elder Liquidamber styraciflua Sweetgum Acer rubrum Maple, Red Liriodendron tulipfera Tulip Poplar Acer saccharinum Maple, Silver Maclura pomifera Osage Orange Acer saccharum Maple, Sugar Magnolia acuminata Cucumber magnolia Aesculus glabra Buckeye, Ohio Nyssa sylvatica Blackgum Aesculus octandra Buckeye, Yellow Ostrya viginiana Ironwood Alnus glutinosa Alder, Common Oxydendron arboream Sourwood Alnus rugosa Alder, Speckled Parthenosisis quinquefolia Virginia Creeper Amelanchier arborea Serviceberry, Shadblow Picea abies Spruce, Norway Amelanchier canadensis Serviceberry, Downy Picea glauca Spruce, White Amelanchier laevis Serviceberry Allegheny Picea mariana Spruce, Black Amopha frutocosa Indigo, False Picea pungens Spruce, Colorado Aralia spinosa Devils-walkingstick Picea rubens Spruce, Red Aronia arbutifolia Chokeberry, Red Pinus nigra Pine, Austrian Aronia melancarpa Chokeberry, Black Pinus resinosa Pine, Red Asimina triloba Pawpaw Pinus rigida Pine, Pitch Betula lenta Birch, Yellow Pinus strobus Pine, White Betula lutea Birch, Sweet Pinus sylvestris Pine, Scots Betula nigra Birch, River Pinus virginiana Pine, Virginia Buddeia davidii Butterfly Bush Platanus acerifolia Sycamore, London Plane Campsis radicans Trumpet Creeper Platanus occidentalis Sycamore, -

Antioxidant Properties of Some Edible Fungi in the Genus Pleurotus

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 8-2005 Antioxidant Properties of Some Edible Fungi in The Genus Pleurotus Sharon Rose Jean-Philippe University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Life Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Jean-Philippe, Sharon Rose, "Antioxidant Properties of Some Edible Fungi in The Genus Pleurotus. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2005. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/2093 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Sharon Rose Jean-Philippe entitled "Antioxidant Properties of Some Edible Fungi in The Genus Pleurotus." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Botany. Karen Hughes, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Beth Mullin, Jay Whelan Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Sharon Rose Jean-Philippe entitled “Antioxidant properties of Some Edible Fungi in The Genus Pleurotus.” I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Botany. -

Trumpet Creeper (Campsis Radicans) Control Herbicide Options

Publication 20-86C October 2020 Trumpet Creeper (Campsis radicans) Control Herbicide Options Dr. E. David Dickens, Forest Productivity Professor; Dr. David Clabo, Forest Productivity Professor; and David J. Moorhead, Emeritus Silviculture Professor; UGA Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources BRIEF Trumpet creeper (Campsis radicans), also known as cow itch vine, trumpet vine, or hummingbird vine, is in the Bignoniaceae family and is native to the eastern United States. Trumpet creeper is frequently found in a variety of southeastern United States forests and can be a competitor in pine stands. If not controlled, it can kill the trees it grows on by canopying over the crowns and not allowing adequate sunlight to get to the tree’s foliage for photo- synthesis. Trumpet creeper is a deciduous, woody vine that can “climb” trees up to 40 feet or greater heights (Photo 1) or form mats on shrubs or grows in clumps lower to the ground (Photo 2). The 1 to 4 inch long green leaves are pinnate, ovate in shape and opposite (Photo 3). The orange to red showy flowers are terminal cymes of 4 to 10 found on the plants during late spring into summer (Photo 4). Large (3 to 6 inches long) seed pods are formed on mature plants in the fall that hold hundreds of seeds (Photo 5). Trumpet creeper control is best performed during active growth periods from mid-June to early October in Georgia. If trumpet creeper has climbed up into a num- ber of trees, a prescribed burn or cutting the vines to groundline may be needed to get the climbing vine down to groundline where foliar active herbicides will be effective. -

Medical Appropriation in the 'Red' Atlantic: Translating a Mi'kmaq

1 Medical Appropriation in the ‘Red’ Atlantic: Translating a Mi’kmaq smallpox cure in the mid-nineteenth century Farrah Lawrence-Mackey University College London Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History and Philosophy of Science Department of Science and Technology Studies 2018 2 I, Farrah Mary Lawrence-Mackey confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 3 ABSTRACT This thesis answers the questions of what was travelling, how, and why, when a Kanien’kehaka woman living amongst the Mi’kmaq at Shubenacadie sold a remedy for smallpox to British and Haligonian colonisers in 1861. I trace the movement of the plant (known as: Mqo’oqewi’k, Indian Remedy, Sarracenia purpurea, and Limonio congener) and knowledges of its use from Britain back across the Atlantic. In exploring how this remedy travelled, why at this time and what contexts were included with the plant’s removal I show that rising scientific racism in the nineteenth century did not mean that Indigenous medical flora and knowledge were dismissed wholesale, as scholars like Londa Schiebinger have suggested. Instead conceptions of indigeneity were fluid, often lending authority to appropriated flora and knowledge while the contexts of nineteenth-century Britain, Halifax and Shubenacadie created the Sarracenia purpurea, Indian Remedy and Mqo’oqewi’k as it moved through and between these spaces. Traditional accounts of bio-prospecting argue that as Indigenous flora moved, Indigenous contexts were consistently stripped away. This process of stripping shapes Indigenous origins as essentialised and static. -

Hieronymus Bock (1498-1554) Und Paolo Boccone (1633-1704) 49-59 Boletus, Band 28, 2005, Heft 1, Seite 49-59

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Boletus - Pilzkundliche Zeitschrift Jahr/Year: 2005 Band/Volume: 28 Autor(en)/Author(s): Dörfelt Heinrich, Heklau Heike Artikel/Article: Historischer Rückblick im Jahr 2004: Hieronymus Bock (1498-1554) und Paolo Boccone (1633-1704) 49-59 Boletus, Band 28, 2005, Heft 1, Seite 49-59 Heinrich Dörfelt & H eike H eklau Historischer Rückblick im Jahr 2004: H ieronymus Bock (1498-1554) undP aolo Boccone (1633-1704) Dörfelt, H. & H eklau, H. (2005): A historical review in the year 2004: H ieronymus Bock (1498-1554) and Paolo Boccone (1633-1704). Boletus 28(1): 49-59 Abstract: Historical reviews shoud be a stimulation for the own work in the present time. The cause of this paper on historical events is the death of H ieronymus Bock in the year 1554 (450 years ago) and of Paolo Boccone in the year 1704 (300 years ago). H. Bock has created a first definition of the fungi after the antiquity in 1539. P. Boccone has publised nummerous new fungi in the years 1674 and 1697. Both were progressists for the contemporary knowledge on fungi. Keywords: fungi, history, systematics, baroque, renaissance,H ieronymus Bock, T ragus , Pao lo Boccone , Paulus Bocconus Zusammenfassung: Die Rückblicke in die Geschichte der Mykologie, die als stimulierende Quelle für eigene Arbeiten gesehen werden sollten, werden fortgesetzt. Zwei Todestage, die sich im Jahr 2004 zum 450. bzw. zum 300. Mal jähren, sind Anlass unserer Betrachtung. Der deutsche Me diziner H ieronymus Bock, Autor eines bedeutenden Kräuterbuches der Renaissance, starb im Jahr 1554, und der Italiener Paolo Boccone , Gelehrter und Mitglied des Zisterzienser-Ordens, im Jahr 1704. -

Gerard's Herbal the OED Defines the Word

Gerard’s Herbal The OED defines the word ‘herbal’ (n) as: ‘a book containing the names and descriptions of herbs, or of plants in general, with their properties and virtues; a treatise in plants.’ Charles Singer, historian of medicine and science, describes herbals as ‘a collection of descriptions of plants usually put together for medical purposes. The term is perhaps now-a-days used most frequently in connection with the finely illustrated works produced by the “fathers of botany” in the fifteenth and sixteenth century.’1 Although the origin of the herbal dates back to ‘remote antiquity’2 the advent of the printing press meant that herbals could be produced in large quantities (in comparison to their earlier manuscript counterparts) with detailed woodcut and metal engraving illustrations. The first herbal printed in Britain was Richard Banckes' Herball of 15253, which was written in plain text. Following Banckes, herbalists such as William Turner and John Gerard gained popularity with their lavishly illustrated herbals. Gerard’s Herbal was originally published in 1597; it is regarded as being one of the best of the printed herbals and is the first herbal to contain an illustration of a potato4. Gerard did Illustration of Gooseberries from not have an enormously interesting life; he was Gerard’s Herbal (1633), demonstrating the intricate detail that ‘apprenticed to Alexander Mason, a surgeon of 5 characterises this text. the Barber–Surgeons' Company’ and probably ‘travelled in Scandinavia and Russia, as he frequently refers to these places in his writing’6. For all his adult life he lived in a tenement with a garden probably belonging to Lord Burghley.