Medical Appropriation in the 'Red' Atlantic: Translating a Mi'kmaq

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

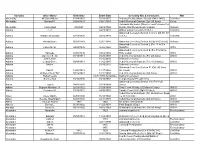

Surname Given Name Birth Date Death Date Cemetery Site & Comments

Surname Given Name Birth Date Death Date Cemetery Site & Comments. War Abernathy William Wilkins 11/24/1825 02/15/1875 Bethany Presby (Home Guard) (1861-1865) Civil War Abernathy Garland P. 03/08/1931 03/01/1984 Iredell Memorial Gardens (Cpl US Army) Korea Rehoboth Methodist (Sherrils Ford/Catawba Co) Abernathy Jimmy Edd 03/20/47 02/02/1969 Bronze Star/Purple Heart) Vietnam Vietnam Adams J. P. 04/25/1881 Willow Valley Cemetery (C.S.A.) Civil War Oakwood Cemetery Section C (Co C 4th NC Inf Adams William McLelland 07/13/1838 02/02/1918 C.S.A.) Civil War Adams Ronald Elam 06/28/1943 12/01/1988 Oakwood Cemetery Section Q (Sp 4 US Army) Vietnam Oakwood Cemetery Section L (Pvt 13 Inf Co Adams Calvin M. Sr. 04/24/1889 05/06/1968 MGOTS) WW I Oakwood Cemetery Section E (Pvt STU Army Adams Talmage 03/05/1899 09/02/1969 TNG Corps) WW I Adams Clarence E., Sr. 08/19/1911 08/20/1993 Iredell Memorial Gardens (Pvt US Army) WW II Adams John Lester 01/15/2010 Belmont Cemetery Adams Leland Orville 09/04/1914 11/02/1987 Iredell Memorial Gardens (Tec 4 US Army) WW II Adams Melvin 04/19/2012 Belmont Cemetery Oakwood Cemetery Section R (Cpl US Army Adams Paul K. 12/20/1919 11/17/1992 Air Corps) WW II Adams William Alfred "Bill" 07/26/1923 12/11/1998 Iredell Memorial Gardens (US Army) WW II Adams Robert Lewis 08/31/1991 burial date Belmont Cemetery Adams Stamey Neil 10/14/1936 10/14/1992 Temple Baptist Pfc US Army Oakwood Cemetery Section Vet (Tec4 US Adcox Floyd A. -

Southern Medical and Surgical Journal

SOUTHERN MEDICAL AND SURGICAL JOURNAL. EDITED BY HENRY F. CAMPBELL, A.M., M. D., GEORGIA PROKES-OR OK BPECIAL AND COMPARATIVE ANATOMY IN TBI MEDICAL COLLEGK OF ROBERT CAMPBELL, A.M..M.D., DBMOSrtTRATOB OF ANATOMY IN THE MEDICAL COLLEGE MEPICAL COLLEGE OF GEORGIA. YOL. XIV.—1858.—NEW SERIES. AUGUSTA, G A: J. MORRIS, PRINTER AND PUBLISHER. 1858. SOUTHERN MEDICAL KM) SURGICAL JOURNAL. (NEW SERIES.) Vol. XIV.] AUGUSTA, GEORGIA, OCTOBER, 1838. [No. 10. ORIGINAL AXD ECLECTIC. ARTICLE XXII. Observations on Malarial Fever. By Joseph Joxes, A.M., M.D., Professor of Physics and Natural Theology in the University of Georgia, Athens; Professor of Chemistry and Pharmacy in the Medical College of Georgia, Augusta; formerly Professor of Medical Chemistry in the Medical College of Savannah. [Continued from page 601 of September Xo. 1858.] Case XXVIII.—Scotch seaman ; age 14 ; light hair, blue eyes, florid complexion; height 5 feet 2 inches; weight 95 lbs. From light ship, lying at the mouth of Savannah river. Was taken sick three days ago. September 16th, 7 o'clock P. M. Face as red as scarlet; skin in a profuse perspiration, which has saturated his thick flannel shirt and wet the bed-clothes. Pulse 100. Eespiration 24 : does not correspond with the flushed appearance of his face. Tem- perature of atmosphere, 88° F. ; temp, of hand, 102 ; temp, un- der tongue, 103.25. Tip and middle of tongue clean and of a bright red color; posterior portion (root) of tongue, coated with yellow fur; tongue rough and perfectly dry. When the finger is passed over the tongue, it feels as dry and harsh as a rough board. -

1835. EXECUTIVE. *L POST OFFICE DEPARTMENT

1835. EXECUTIVE. *l POST OFFICE DEPARTMENT. Persons employed in the General Post Office, with the annual compensation of each. Where Compen Names. Offices. Born. sation. Dol. cts. Amos Kendall..., Postmaster General.... Mass. 6000 00 Charles K. Gardner Ass't P. M. Gen. 1st Div. N. Jersey250 0 00 SelahR. Hobbie.. Ass't P. M. Gen. 2d Div. N. York. 2500 00 P. S. Loughborough Chief Clerk Kentucky 1700 00 Robert Johnson. ., Accountant, 3d Division Penn 1400 00 CLERKS. Thomas B. Dyer... Principal Book Keeper Maryland 1400 00 Joseph W. Hand... Solicitor Conn 1400 00 John Suter Principal Pay Clerk. Maryland 1400 00 John McLeod Register's Office Scotland. 1200 00 William G. Eliot.. .Chie f Examiner Mass 1200 00 Michael T. Simpson Sup't Dead Letter OfficePen n 1200 00 David Saunders Chief Register Virginia.. 1200 00 Arthur Nelson Principal Clerk, N. Div.Marylan d 1200 00 Richard Dement Second Book Keeper.. do.. 1200 00 Josiah F.Caldwell.. Register's Office N. Jersey 1200 00 George L. Douglass Principal Clerk, S. Div.Kentucky -1200 00 Nicholas Tastet Bank Accountant Spain. 1200 00 Thomas Arbuckle.. Register's Office Ireland 1100 00 Samuel Fitzhugh.., do Maryland 1000 00 Wm. C,Lipscomb. do : for) Virginia. 1000 00 Thos. B. Addison. f Record Clerk con-> Maryland 1000 00 < routes and v....) Matthias Ross f. tracts, N. Div, N. Jersey1000 00 David Koones Dead Letter Office Maryland 1000 00 Presley Simpson... Examiner's Office Virginia- 1000 00 Grafton D. Hanson. Solicitor's Office.. Maryland 1000 00 Walter D. Addison. Recorder, Div. of Acc'ts do.. -

Gerard's Herbal the OED Defines the Word

Gerard’s Herbal The OED defines the word ‘herbal’ (n) as: ‘a book containing the names and descriptions of herbs, or of plants in general, with their properties and virtues; a treatise in plants.’ Charles Singer, historian of medicine and science, describes herbals as ‘a collection of descriptions of plants usually put together for medical purposes. The term is perhaps now-a-days used most frequently in connection with the finely illustrated works produced by the “fathers of botany” in the fifteenth and sixteenth century.’1 Although the origin of the herbal dates back to ‘remote antiquity’2 the advent of the printing press meant that herbals could be produced in large quantities (in comparison to their earlier manuscript counterparts) with detailed woodcut and metal engraving illustrations. The first herbal printed in Britain was Richard Banckes' Herball of 15253, which was written in plain text. Following Banckes, herbalists such as William Turner and John Gerard gained popularity with their lavishly illustrated herbals. Gerard’s Herbal was originally published in 1597; it is regarded as being one of the best of the printed herbals and is the first herbal to contain an illustration of a potato4. Gerard did Illustration of Gooseberries from not have an enormously interesting life; he was Gerard’s Herbal (1633), demonstrating the intricate detail that ‘apprenticed to Alexander Mason, a surgeon of 5 characterises this text. the Barber–Surgeons' Company’ and probably ‘travelled in Scandinavia and Russia, as he frequently refers to these places in his writing’6. For all his adult life he lived in a tenement with a garden probably belonging to Lord Burghley. -

Yuma Academic Center Arizonastate University— ASU@Yuma

Arizona Western College Northern Arizona University— Yuma Branch Campus University of Arizona— Yuma Academic Center ArizonaState University— ASU@Yuma Community College Changes Lives When graduation rolls around every year, the community gets a quick visual reminder of the culmi- nation of several years worth of effort. Our students are both young and old, many are parents, and most are working full- or part-time while attending college. While we have the pleasure of working with them every week of every semester, and understanding both their struggles and their dreams, the biggest part of their effort goes on behind the scenes for many people in Yuma and La Paz Counties. And yet, you benefit. You benefit when your neighbors get good jobs and can contribute to the tax base. You benefit when your company can hire skilled, productive employees. You benefit when voters in your area understand the issues as they fill out a ballot. At AWC, we also benefit when students complete their studies and accept their diploma – colleges are increasingly measured on how they prepare students to persist in school, and to complete. Arizona Western College has the highest retention and transfer rate in the state. Our students not only finish with us, but they also transfer to nearby universities, where they finish their bachelor’s degree at a rate that beats the state average for college transfers, and in greater numbers than students who went directly to a university. Winning the statistical race is not the reason we are happy, although that’s nice. We are happy because the students we work with have personal, meaningful dreams. -

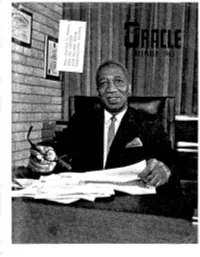

1965 December, Oracle

,':--, r., cd " " <IJ ,c/" ••L" -"' 0-: ,~ c," [d r:; H "": c, q"" r~., " "'-',' oj G'" ::0.-; "0' -,-I ,..--1 (0 m -," h (71" I--J ,-0 0 ,r:; :1::; 1.":', 0 C'., 'J) r.:" '" ('J -cr; m -r-! r., !:-I ~"\ 'rJ " r~] ~.0 PJ '" ,-I H" "'''''(' OMEGA PSI PHI FRATERNITY. Inc. I Notes J1J:om the Bditoi (Founded November 17, 1911) ReTURN OF PHOTOS FOUNDERS Deal' Brothel's: PROF. FRANK COLEMAN 1232 Girard Street, N.E., Wash., D.C, We receive numeroUs requests for return DR. OSCAR J, COOPER 1621 W. Jefferson St., Phila., Fa. DR. ERNEST E. JUST . .' .,........ • . .. Deceased of photos .. In most instances we make REV. EDGAR ~ LOVE ... 2416 Montebelo Terrace, BaIt., Md. an -all out effort to comply with your wishes. This however; entai'ls an expense GRAND OFFICERS that is not computible to our budget. With GEORGE E, MEARES, Grand BasUeus , .... 155 Willoughby Ave., Brooklyn, N,Y. the continllous ell.pansion of the "Oracle", ELLIS F. CORBETT, 1st Vice G"and BasliellS IllZ Benbow Road, Greensboro, N.C, DORSEY C, MILLER, 2nd Vice Grand Baslleus .. 727 W. 5th Street, Ocala, Fla, we find that We can no lon-gel' absorb WALTER H. RIDDICK, Grand Keeper of ReeD rels & Seal 1038 Chapel St., Norfoll~, Va, this cost, Thus we are requesting. that JESSE B. BLA YTON, SR., Grand Keeper of Finance :3462 Del Mar Lane, N.W., Atlanta, Ga. in the future, requests for return of photos AUDREY PRUITT, Editor of the ORACLE.. 1123 N,E, 4th St., Oklahoma City, Olda. MARION W. GARNETT, Grand Counselor " 109 N. -

Descendants of Stephen Hopkins of the Mayflower

Descendants of Stephen Hopkins of the Mayflower Generation No. 1 2 1 1. STEPHEN HOPKINS (STEPHEN ) (Source: "Mayflower Families Through Five Generations", volume six, "Hopkins", published by General Society of Mayflower Descendants, 1992..) was born Abt. 1580 in England, and died Bet. June 6 - July 17, 1644 in Plymouth, MA. He married (1) NAME UNKNOWN. She was born in England, and died Bef. 1617 in England. He married (2) ELIZABETH FISHER Abt. February 19, 1617/18 in Whitechapel, London, England. She died Aft. February 4, 1638 in Plymouth. Notes for STEPHEN HOPKINS: Stephen Hopkins sailed on the Mayflower in 1620. Was one of the Londoners or strangers recruited for the voyage. He was called Master, and only two other of the 17 free men on the voyage were styled. Stephen was called a tanner or leather maker at the time of the Mayflower voyage. He seems to have originated from the family of Hopkins, alias Seborne, located for several generations at Wortley, Wooton Underedge, Gloucester County, England. Although Stephen of the Mayflower may well have been a son of Stephen Hopkins, a clothier of Wortley, who also had a son Robert Hopkins of London. Two indentured servants (Edward Doty and Edward Lister) came with Hopkins on the Mayflower. Stephen Hopkins was probably the young man of that name who served as minister's clerk on the vessel Sea Venture which sailed from London June 2, 1609, bound for Virginia. The ship was severely damaged in a hurricane and the company was washed ashore on the Bermuda "Isle of the Divels" on July 28, 1609. -

Ii ABSTRACT HARRIS, GEOFFREY SHIELDS

ABSTRACT HARRIS, GEOFFREY SHIELDS. Toward a New Whig Interpretation of History: Common Schools in Burke County, North Carolina, from 1853 to 1861. (Under the direction of Dr. James Crisp.) This thesis will examine both the history and historiography of the common school movement in western North Carolina in the last decades of the antebellum period. In particular, it will focus on common schools in Burke County during the years of school board chairman James Avery’s tenure (1853-1861). The attendance records James Avery kept during his tenure as chairman of the county board of common schools (now located in his personal papers at the Southern Historical Collection) provide a wealth of previously unexamined data relating to the operation of common schools at the county level. A detailed examination of these records yields new insights into common schools in antebellum North Carolina. These insights have both specific and general application. First, and most specifically, an analysis of Avery’s records fills a historical gap in our understanding of common schools in Burke County (a county whose official antebellum records on education have largely been destroyed). Second, and more generally, it provides a reliable measure of popular support for and participation in an institution that historians have alternately described as a tool of elite social control and an expression of yeoman democracy. By shifting the focus of the common school narrative from the state superintendent’s office to the county level, this study challenges several entrenched features of North Carolina common school historiography and provides a new window into the rhetoric and reality of class and sectional identity in antebellum North Carolina. -

Ministers of ‘The Black Art’: the Engagement of British Clergy with Photography, 1839-1914

Ministers of ‘the Black Art’: the engagement of British clergy with photography, 1839-1914 Submitted by James Downs to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in March 2018 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signature: ………………………………………………………….. Abstract 1 Ministers of ‘the Black Art’: the engagement of British clergy with photography, 1839- 1914 This thesis examines the work of ordained clergymen, of all denominations, who were active photographers between 1839 and the beginning of World War One: its primary aim is to investigate the extent to which a relationship existed between the religious culture of the individual clergyman and the nature of his photographic activities. Ministers of ‘the Black Art’ makes a significant intervention in the study of the history of photography by addressing a major weakness in existing work. Taking an interdisciplinary approach, the research draws on a wide range of primary and secondary sources such as printed books, sermons, religious pamphlets, parish and missionary newsletters, manuscript diaries, correspondence, notebooks, biographies and works of church history, as well as visual materials including original glass plate negatives, paper prints and lantern slides held in archival collections, postcards, camera catalogues, photographic ephemera and photographically-illustrated books. -

Continuity and Transformation in the World Polity: Toward a Neorealist Synthesis Reviewed Work(S): Theory of International Politics

Review: Continuity and Transformation in the World Polity: Toward a Neorealist Synthesis Reviewed Work(s): Theory of International Politics. by Kenneth N. Waltz Review by: John Gerard Ruggie Source: World Politics, Vol. 35, No. 2 (Jan., 1983), pp. 261-285 Published by: Cambridge University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2010273 Accessed: 04-10-2017 18:15 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms Cambridge University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to World Politics This content downloaded from 128.103.193.216 on Wed, 04 Oct 2017 18:15:39 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms CONTINUITY AND TRANSFORMATION IN THE WORLD POLITY: Toward a Neorealist Synthesis By JOHN GERARD RUGGIE* Kenneth N. Waltz, Theory of International Politics. Reading, Mass.: Addison- Wesley Publishing Company, 1979, 251 pp., $7.95 (paper). IN The Rules of Sociological Method, Emile Durkheim sought to es- tablish the "social milieu," or society itself, "as the determining factor of collective evolution." In turn, he took society to reflect not the mere summation of individuals -

“Jogging Along with and Without James Logan: Early Plant Science in Philadelphia”

1 Friday, 19 September 2014, 1:30–3:00 p.m.: Panel II: “Leaves” “Jogging Along With and Without James Logan: Early Plant Science in Philadelphia” Joel T. Fry, Bartram's Garden Presented at the ― James Logan and the Networks of Atlantic Culture and Politics, 1699-1751 conference Philadelphia, PA, 18-20 September 2014 Please do not cite, quote, or circulate without written permission from the author These days, John Bartram (1699-1777) and James Logan (1674-1751) are routinely recognized as significant figures in early American science, and particularly botanic science, even if exactly what they accomplished is not so well known. Logan has been described by Brooke Hindle as “undoubtedly the most distinguished scientist in the area” and “It was in botany that James Logan made his greatest contribution to science.” 1 Raymond Stearns echoed, “Logan’s greatest contribution to science was in botany.”2 John Bartram has been repeatedly crowned as the “greatest natural botanist in the world” by Linnaeus no less, since the early 19th century, although tracing the source for that quote and claim can prove difficult.3 Certainly Logan was a great thinker and scholar, along with his significant political and social career in early Pennsylvania. Was Logan a significant botanist—maybe not? John Bartram too may not have been “the greatest natural botanist in the world,” but he was very definitely a unique genius in his own right, and almost certainly by 1750 Bartram was the best informed scientist in the Anglo-American world on the plants of eastern North America. There was a short period of active scientific collaboration in botany between Bartram and Logan, which lasted at most through the years 1736 to 1738. -

Of the Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation

Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania Vol. 26, No. 1 Bulletin Spring 2014 of the Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation Inside 4 Duets on display 4 Open House 2014 4 William Andrew 4 Illustrated mushroom Archer papers books, part 2 Above right, Tulipe des jardins. Tulipa gesneriana L. [Tulipa gesnerana Linnaeus, Liliaceae], stipple engraving on paper by P. F. Le Grand, 49 × 32.5 cm, after an original by Gerard van Spaendonck (Holland/France, 1746–1822) for his Fleurs Sessinées d’après Nature (Paris, L’Auteur, au Jardin des Plantes, 1801, pl. 4), HI Art accession no. 2078. Below left, Parrot tulips [Tulipa Linnaeus, Liliaceae], watercolor on paper by Rose Pellicano (Italy/United States), 1998, 56 × 42.5 cm, HI Art accession no. 7405. News from the Art Department Duets exhibition opens The inspiration for the exhibition Duets 1746–1822) has done so with the began with two artworks of trumpet subtle tonality of a monochromatic vine, which were created by the stipple engraving and Rose Pellicano 18th-century, German/English artist (Italy/United States) with rich layers Georg Ehret and the contemporary of watercolor. The former inspired Italian artist Marilena Pistoia. Visitors a legion of botanical artists while frequently request to view a selection teaching at the Jardin des Plantes in of the Institute’s collection of 255 Ehret Paris, and the latter, whose work is and 227 Pistoia original paintings. One inspired by French 18th- and 19th- day we displayed side-by-side the two century artists, carries on this tradition paintings (above left and right) and noticed of exhibiting, instructing and inspiring not only the similarity of composition up-and-coming botanical artists.