Ii ABSTRACT HARRIS, GEOFFREY SHIELDS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

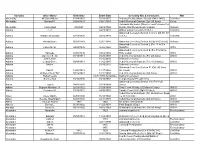

Surname Given Name Birth Date Death Date Cemetery Site & Comments

Surname Given Name Birth Date Death Date Cemetery Site & Comments. War Abernathy William Wilkins 11/24/1825 02/15/1875 Bethany Presby (Home Guard) (1861-1865) Civil War Abernathy Garland P. 03/08/1931 03/01/1984 Iredell Memorial Gardens (Cpl US Army) Korea Rehoboth Methodist (Sherrils Ford/Catawba Co) Abernathy Jimmy Edd 03/20/47 02/02/1969 Bronze Star/Purple Heart) Vietnam Vietnam Adams J. P. 04/25/1881 Willow Valley Cemetery (C.S.A.) Civil War Oakwood Cemetery Section C (Co C 4th NC Inf Adams William McLelland 07/13/1838 02/02/1918 C.S.A.) Civil War Adams Ronald Elam 06/28/1943 12/01/1988 Oakwood Cemetery Section Q (Sp 4 US Army) Vietnam Oakwood Cemetery Section L (Pvt 13 Inf Co Adams Calvin M. Sr. 04/24/1889 05/06/1968 MGOTS) WW I Oakwood Cemetery Section E (Pvt STU Army Adams Talmage 03/05/1899 09/02/1969 TNG Corps) WW I Adams Clarence E., Sr. 08/19/1911 08/20/1993 Iredell Memorial Gardens (Pvt US Army) WW II Adams John Lester 01/15/2010 Belmont Cemetery Adams Leland Orville 09/04/1914 11/02/1987 Iredell Memorial Gardens (Tec 4 US Army) WW II Adams Melvin 04/19/2012 Belmont Cemetery Oakwood Cemetery Section R (Cpl US Army Adams Paul K. 12/20/1919 11/17/1992 Air Corps) WW II Adams William Alfred "Bill" 07/26/1923 12/11/1998 Iredell Memorial Gardens (US Army) WW II Adams Robert Lewis 08/31/1991 burial date Belmont Cemetery Adams Stamey Neil 10/14/1936 10/14/1992 Temple Baptist Pfc US Army Oakwood Cemetery Section Vet (Tec4 US Adcox Floyd A. -

Southern Medical and Surgical Journal

SOUTHERN MEDICAL AND SURGICAL JOURNAL. EDITED BY HENRY F. CAMPBELL, A.M., M. D., GEORGIA PROKES-OR OK BPECIAL AND COMPARATIVE ANATOMY IN TBI MEDICAL COLLEGK OF ROBERT CAMPBELL, A.M..M.D., DBMOSrtTRATOB OF ANATOMY IN THE MEDICAL COLLEGE MEPICAL COLLEGE OF GEORGIA. YOL. XIV.—1858.—NEW SERIES. AUGUSTA, G A: J. MORRIS, PRINTER AND PUBLISHER. 1858. SOUTHERN MEDICAL KM) SURGICAL JOURNAL. (NEW SERIES.) Vol. XIV.] AUGUSTA, GEORGIA, OCTOBER, 1838. [No. 10. ORIGINAL AXD ECLECTIC. ARTICLE XXII. Observations on Malarial Fever. By Joseph Joxes, A.M., M.D., Professor of Physics and Natural Theology in the University of Georgia, Athens; Professor of Chemistry and Pharmacy in the Medical College of Georgia, Augusta; formerly Professor of Medical Chemistry in the Medical College of Savannah. [Continued from page 601 of September Xo. 1858.] Case XXVIII.—Scotch seaman ; age 14 ; light hair, blue eyes, florid complexion; height 5 feet 2 inches; weight 95 lbs. From light ship, lying at the mouth of Savannah river. Was taken sick three days ago. September 16th, 7 o'clock P. M. Face as red as scarlet; skin in a profuse perspiration, which has saturated his thick flannel shirt and wet the bed-clothes. Pulse 100. Eespiration 24 : does not correspond with the flushed appearance of his face. Tem- perature of atmosphere, 88° F. ; temp, of hand, 102 ; temp, un- der tongue, 103.25. Tip and middle of tongue clean and of a bright red color; posterior portion (root) of tongue, coated with yellow fur; tongue rough and perfectly dry. When the finger is passed over the tongue, it feels as dry and harsh as a rough board. -

1835. EXECUTIVE. *L POST OFFICE DEPARTMENT

1835. EXECUTIVE. *l POST OFFICE DEPARTMENT. Persons employed in the General Post Office, with the annual compensation of each. Where Compen Names. Offices. Born. sation. Dol. cts. Amos Kendall..., Postmaster General.... Mass. 6000 00 Charles K. Gardner Ass't P. M. Gen. 1st Div. N. Jersey250 0 00 SelahR. Hobbie.. Ass't P. M. Gen. 2d Div. N. York. 2500 00 P. S. Loughborough Chief Clerk Kentucky 1700 00 Robert Johnson. ., Accountant, 3d Division Penn 1400 00 CLERKS. Thomas B. Dyer... Principal Book Keeper Maryland 1400 00 Joseph W. Hand... Solicitor Conn 1400 00 John Suter Principal Pay Clerk. Maryland 1400 00 John McLeod Register's Office Scotland. 1200 00 William G. Eliot.. .Chie f Examiner Mass 1200 00 Michael T. Simpson Sup't Dead Letter OfficePen n 1200 00 David Saunders Chief Register Virginia.. 1200 00 Arthur Nelson Principal Clerk, N. Div.Marylan d 1200 00 Richard Dement Second Book Keeper.. do.. 1200 00 Josiah F.Caldwell.. Register's Office N. Jersey 1200 00 George L. Douglass Principal Clerk, S. Div.Kentucky -1200 00 Nicholas Tastet Bank Accountant Spain. 1200 00 Thomas Arbuckle.. Register's Office Ireland 1100 00 Samuel Fitzhugh.., do Maryland 1000 00 Wm. C,Lipscomb. do : for) Virginia. 1000 00 Thos. B. Addison. f Record Clerk con-> Maryland 1000 00 < routes and v....) Matthias Ross f. tracts, N. Div, N. Jersey1000 00 David Koones Dead Letter Office Maryland 1000 00 Presley Simpson... Examiner's Office Virginia- 1000 00 Grafton D. Hanson. Solicitor's Office.. Maryland 1000 00 Walter D. Addison. Recorder, Div. of Acc'ts do.. -

Medical Appropriation in the 'Red' Atlantic: Translating a Mi'kmaq

1 Medical Appropriation in the ‘Red’ Atlantic: Translating a Mi’kmaq smallpox cure in the mid-nineteenth century Farrah Lawrence-Mackey University College London Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History and Philosophy of Science Department of Science and Technology Studies 2018 2 I, Farrah Mary Lawrence-Mackey confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 3 ABSTRACT This thesis answers the questions of what was travelling, how, and why, when a Kanien’kehaka woman living amongst the Mi’kmaq at Shubenacadie sold a remedy for smallpox to British and Haligonian colonisers in 1861. I trace the movement of the plant (known as: Mqo’oqewi’k, Indian Remedy, Sarracenia purpurea, and Limonio congener) and knowledges of its use from Britain back across the Atlantic. In exploring how this remedy travelled, why at this time and what contexts were included with the plant’s removal I show that rising scientific racism in the nineteenth century did not mean that Indigenous medical flora and knowledge were dismissed wholesale, as scholars like Londa Schiebinger have suggested. Instead conceptions of indigeneity were fluid, often lending authority to appropriated flora and knowledge while the contexts of nineteenth-century Britain, Halifax and Shubenacadie created the Sarracenia purpurea, Indian Remedy and Mqo’oqewi’k as it moved through and between these spaces. Traditional accounts of bio-prospecting argue that as Indigenous flora moved, Indigenous contexts were consistently stripped away. This process of stripping shapes Indigenous origins as essentialised and static. -

Yuma Academic Center Arizonastate University— ASU@Yuma

Arizona Western College Northern Arizona University— Yuma Branch Campus University of Arizona— Yuma Academic Center ArizonaState University— ASU@Yuma Community College Changes Lives When graduation rolls around every year, the community gets a quick visual reminder of the culmi- nation of several years worth of effort. Our students are both young and old, many are parents, and most are working full- or part-time while attending college. While we have the pleasure of working with them every week of every semester, and understanding both their struggles and their dreams, the biggest part of their effort goes on behind the scenes for many people in Yuma and La Paz Counties. And yet, you benefit. You benefit when your neighbors get good jobs and can contribute to the tax base. You benefit when your company can hire skilled, productive employees. You benefit when voters in your area understand the issues as they fill out a ballot. At AWC, we also benefit when students complete their studies and accept their diploma – colleges are increasingly measured on how they prepare students to persist in school, and to complete. Arizona Western College has the highest retention and transfer rate in the state. Our students not only finish with us, but they also transfer to nearby universities, where they finish their bachelor’s degree at a rate that beats the state average for college transfers, and in greater numbers than students who went directly to a university. Winning the statistical race is not the reason we are happy, although that’s nice. We are happy because the students we work with have personal, meaningful dreams. -

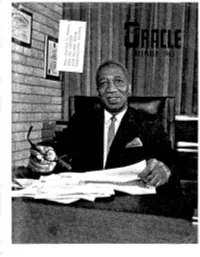

1965 December, Oracle

,':--, r., cd " " <IJ ,c/" ••L" -"' 0-: ,~ c," [d r:; H "": c, q"" r~., " "'-',' oj G'" ::0.-; "0' -,-I ,..--1 (0 m -," h (71" I--J ,-0 0 ,r:; :1::; 1.":', 0 C'., 'J) r.:" '" ('J -cr; m -r-! r., !:-I ~"\ 'rJ " r~] ~.0 PJ '" ,-I H" "'''''(' OMEGA PSI PHI FRATERNITY. Inc. I Notes J1J:om the Bditoi (Founded November 17, 1911) ReTURN OF PHOTOS FOUNDERS Deal' Brothel's: PROF. FRANK COLEMAN 1232 Girard Street, N.E., Wash., D.C, We receive numeroUs requests for return DR. OSCAR J, COOPER 1621 W. Jefferson St., Phila., Fa. DR. ERNEST E. JUST . .' .,........ • . .. Deceased of photos .. In most instances we make REV. EDGAR ~ LOVE ... 2416 Montebelo Terrace, BaIt., Md. an -all out effort to comply with your wishes. This however; entai'ls an expense GRAND OFFICERS that is not computible to our budget. With GEORGE E, MEARES, Grand BasUeus , .... 155 Willoughby Ave., Brooklyn, N,Y. the continllous ell.pansion of the "Oracle", ELLIS F. CORBETT, 1st Vice G"and BasliellS IllZ Benbow Road, Greensboro, N.C, DORSEY C, MILLER, 2nd Vice Grand Baslleus .. 727 W. 5th Street, Ocala, Fla, we find that We can no lon-gel' absorb WALTER H. RIDDICK, Grand Keeper of ReeD rels & Seal 1038 Chapel St., Norfoll~, Va, this cost, Thus we are requesting. that JESSE B. BLA YTON, SR., Grand Keeper of Finance :3462 Del Mar Lane, N.W., Atlanta, Ga. in the future, requests for return of photos AUDREY PRUITT, Editor of the ORACLE.. 1123 N,E, 4th St., Oklahoma City, Olda. MARION W. GARNETT, Grand Counselor " 109 N. -

Descendants of Stephen Hopkins of the Mayflower

Descendants of Stephen Hopkins of the Mayflower Generation No. 1 2 1 1. STEPHEN HOPKINS (STEPHEN ) (Source: "Mayflower Families Through Five Generations", volume six, "Hopkins", published by General Society of Mayflower Descendants, 1992..) was born Abt. 1580 in England, and died Bet. June 6 - July 17, 1644 in Plymouth, MA. He married (1) NAME UNKNOWN. She was born in England, and died Bef. 1617 in England. He married (2) ELIZABETH FISHER Abt. February 19, 1617/18 in Whitechapel, London, England. She died Aft. February 4, 1638 in Plymouth. Notes for STEPHEN HOPKINS: Stephen Hopkins sailed on the Mayflower in 1620. Was one of the Londoners or strangers recruited for the voyage. He was called Master, and only two other of the 17 free men on the voyage were styled. Stephen was called a tanner or leather maker at the time of the Mayflower voyage. He seems to have originated from the family of Hopkins, alias Seborne, located for several generations at Wortley, Wooton Underedge, Gloucester County, England. Although Stephen of the Mayflower may well have been a son of Stephen Hopkins, a clothier of Wortley, who also had a son Robert Hopkins of London. Two indentured servants (Edward Doty and Edward Lister) came with Hopkins on the Mayflower. Stephen Hopkins was probably the young man of that name who served as minister's clerk on the vessel Sea Venture which sailed from London June 2, 1609, bound for Virginia. The ship was severely damaged in a hurricane and the company was washed ashore on the Bermuda "Isle of the Divels" on July 28, 1609. -

Draw ^Ballot Goal to Go Committee Fireman to Install Ts Retained By

k*;*i!*^?sy«?WTpf5^ : ••••••- ;>v ••' • -riv- •''•::•••• •'•;••<: •I:'---'?• ;••:•:, if: v,*; .;^?^"''j*vv.^^;.:v*S:?.rs^-'^:'? v,;^J«R:.",v'' • >;;•£> -vv!'-v^-- *•'* -i^.. ,;.:-;\-;7,-.?v.'N: ., • . •••:..• '••-.•;!,ws;fi!.';."r:i'''h ''I-.;. •' •• ;.li..v-Vpi^^'.*;^^f?<;.v'.**'SJ«'..'* >,'•!• :\^ v;.*;1.;'-^ ".'I,-'••.• ••'•': v.^'.r?-,;' •.; ' :y.:v"""". '" . ". ' - ••' • • "'• ''•- -'" ••"••' ' ' :'•.•"•'•".•••'"• •"•;• •••^-'•" ''•'•' 7?""p''. • '•(,; '•£., ."<••'•-' " J •''.: .' —' ••' • tV^i:' "v ,'"•: ; -. • • ^ KJ. ;••"••• •";i 'Twenty-two *» nrtHttion^of fluorides | will be served by Mrs. •:O. •I mental basis have bam expressed wflBdartwiertinealtAMJ -to t CM* now>; or wait until the controlled s^anTnel —~_~_~ jtnd foot traveler r Iriurinduring* 195018501, byv the United States obtain the necessary factual sta- tistics ofja completed, controlled experimental work is completed. The Past Councilors' Club win To Senior Explains Public Health Service, State and •*> Dressings for the leper Skalih A postal expressing your opin- meet Monday night at jjhe home of were Judith Bar- Territorial Dental Health Direc- study.: • • .:;'/:•. :•.*•,"'••.. '• ion on this matter and sent to theMrs. Eleanor South Africa will.be made tors' Association; American Den- In answer to the thought of a pttw^H. Patricia day at the meeting of the D MOBILIZE GIVE mass medication, we are now add- Board of Health will help in mak- Hancy McDonald, Ter- v'') ^Benefits o tal Association, American Public j ing this decision. County ^Women's Osteopath^ / l^o one and a holf.parts, per million Health Association, New Jersey ing vitamin "A" to oleomargarine, Local Scouts Visit Susan Bemhart, Mary- FOR DEIWSE ••' By WILLIAM P. SMITH Uiary in the home of Mrs t> NOW! produces the desirable effect of re- Dental Society; Essex County Den- vitamin "B" to. -

Cumulative Watershed Effects of Fuel Management in the Western United States Elliot, William J.; Miller, Ina Sue; Audin, Lisa

United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Rocky Mountain Research Station General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-231 January 2010 Cumulative Watershed Effects of Fuel Management in the Western United States Elliot, William J.; Miller, Ina Sue; Audin, Lisa. Eds. 2010. Cumulative watershed effects of fuel management in the western United States. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-231. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 299 p. ABSTRACT Fire suppression in the last century has resulted in forests with excessive amounts of biomass, leading to more severe wildfires, covering greater areas, requiring more resources for suppression and mitigation, and causing increased onsite and offsite damage to forests and watersheds. Forest managers are now attempting to reduce this accumulated biomass by thinning, prescribed fire, and other management activities. These activities will impact watershed health, particularly as larger areas are treated and treatment activities become more widespread in space and in time. Management needs, laws, social pressures, and legal findings have underscored a need to synthesize what we know about the cumulative watershed effects of fuel management activities. To meet this need, a workshop was held in Provo, Utah, on April, 2005, with 45 scientists and watershed managers from throughout the United States. At that meeting, it was decided that two syntheses on the cumulative watershed effects of fuel management would be developed, one for the eastern United States, and one for the western United States. For the western synthesis, 14 chapters were defined covering fire and forests, machinery, erosion processes, water yield and quality, soil and riparian impacts, aquatic and landscape effects, and predictive tools and procedures. -

Natural Resource Condition Assessment Horseshoe Bend National Military Park

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Natural Resource Condition Assessment Horseshoe Bend National Military Park Natural Resource Report NPS/SECN/NRR—2015/981 ON THE COVER Photo of the Tallapoosa River, viewed from Horseshoe Bend National Military Park Photo Courtesy of Elle Allen Natural Resource Condition Assessment Horseshoe Bend National Military Park Natural Resource Report NPS/SECN/NRR—2015/981 JoAnn M. Burkholder, Elle H. Allen, Stacie Flood, and Carol A. Kinder Center for Applied Aquatic Ecology North Carolina State University 620 Hutton Street, Suite 104 Raleigh, NC 27606 June 2015 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate comprehensive information and analysis about natural resources and related topics concerning lands managed by the National Park Service. The series supports the advancement of science, informed decision-making, and the achievement of the National Park Service mission. The series also provides a forum for presenting more lengthy results that may not be accepted by publications with page limitations. All manuscripts in the series receive the appropriate level of peer review to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and designed and published in a professional manner. -

The King's Mountain Men, the Story of the Battle, with Sketches of The

THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY 9733364 W58k ILLINOIS HISTORICAL SDRVW i THE KING'S MOUNTAIN MEN THE STORY OF THE BATTLE, WITH SKETCHES OF THE AMERIGAN SOLDIERS WHO TOOK PART KATHRINE KEOGH WHITE Author of 'ABRAM RYAN. Poet-Priest of the South;'* "THE LAND PIRATES OF THE SOUTH;" "THE GANDER- TOURNAMENT OF THE SOUTHERN MOUNTAINS;" Etc. DAYTON, VIRGINIA JOSEPH K. RUEBUSH COMPANY vm COPYRIGHT BY JOSEPH K. RUEBUSH CO. 1924 DEDICATED TO MY BROTHER, WILLIAM THOMAS WARREN WHITE Student, Educator and Scholar r 54307; i The Edition of this Book Has Been Limited to Five Hundred Copies SECTION ONE Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign http://www.archive.org/details/kingsmountainmenOOwhit CONTENTS SECTION ONE PREFACE Page I. The Battle of King's Mountain 3 II. Watauga and Its Records 6 III. General John Sevier 64 IV. Letter by Draper to Martin 68 V. Letters by Christian to Draper 79 VI. Franklin and the Whites 97 VII. Militia Rosters 103 VIII. Incident in the Life of Alexander Moore 105 IX. Greer and McElwee Data 107 X. Diary of Captain Alexander Chesney 108 XI. Sundry Pension Declarations 113 SECTION TWO Personal Sketches of King's Mountain Soldiers APPENDIX Tennessee Revolutionary Pensioners List BIBLIOGRAPHY INDEX PREFACE The list in this book, of the heroes who won the battle of King's Mountain, does not assume to be complete. So far as I am aware, no rosters are in existence. Historians are not agreed as to the number of the Americans who were in the expedition. -

North Carolina Listings in the National Register of Historic Places As of 9/30/2015 Alphabetical by County

North Carolina State Historic Preservation Office http://www.hpo.ncdcr.gov North Carolina Listings in the National Register of Historic Places as of 9/30/2015 Alphabetical by county. Listings with an http:// address have an online PDF of the nomination. Click address to view the PDF. Text is searchable in all PDFs insofar as possible with scans made from old photocopies. Multiple Property Documentation Form PDFs are now available at http://www.hpo.ncdcr.gov/MPDF-PDFs.pdf Date shown is date listed in the National Register. Alamance County Alamance Battleground State Historic Site (Alamance vicinity) 2/26/1970 http://www.hpo.ncdcr.gov/nr/AM0001.pdf Alamance County Courthouse (Graham ) 5/10/1979 http://www.hpo.ncdcr.gov/nr/AM0008.pdf Alamance Hotel (Burlington ) 5/31/1984 http://www.hpo.ncdcr.gov/nr/AM0613.pdf Alamance Mill Village Historic District (Alamance ) 8/16/2007 http://www.hpo.ncdcr.gov/nr/AM0537.pdf Allen House (Alamance vicinity) 2/26/1970 http://www.hpo.ncdcr.gov/nr/AM0002.pdf Altamahaw Mill Office (Altamahaw ) 11/20/1984 http://www.hpo.ncdcr.gov/nr/AM0486.pdf (former) Atlantic Bank and Trust Company Building (Burlington ) 5/31/1984 http://www.hpo.ncdcr.gov/nr/AM0630.pdf Bellemont Mill Village Historic District (Bellemont ) 7/1/1987 http://www.hpo.ncdcr.gov/nr/AM0040.pdf Beverly Hills Historic District (Burlington ) 8/5/2009 http://www.hpo.ncdcr.gov/nr/AM0694.pdf Hiram Braxton House (Snow Camp vicinity) 11/22/1993 http://www.hpo.ncdcr.gov/nr/AM0058.pdf Charles F. and Howard Cates Farm (Mebane vicinity) 9/24/2001 http://www.hpo.ncdcr.gov/nr/AM0326.pdf