Varia Bibliographica a CLUSIUS VARIANT the Works of Charles De

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

English Roots

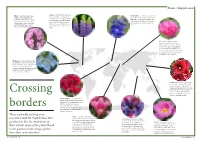

Plants / English roots Lupin – cultivated for thousands of Phlox – arrived in Europe from Delphinium – modern day varieties are years, originally as a fodder plant, Virginia, North America in the the result of interbreeding of species from as far apart as ancient Egypt and the early 18th century before crossing many parts of the world, from the Swiss Peruvian Andes. The tall colourful the channel a century later. Many Alps to Siberia. They have been a part of spires popular in English gardens varieties have been bred since not the English garden since at least Tudor have their origin in North American only in England but also in the times. species that arrived in Britain in the Netherlands and United States. 1820s. Rose – the English rose is the result of centuries of breeding of many varieties of rose from around world. One of these is the Damask rose, named after the Syrian city of Damascus, famous for its fragrance. It is thought to have first been brought to England by the Crusaders. Hydrangea – first introduced from Pennsylvania, North America in 1736. In the nineteenth century they became a favourite of plant hunters and botanists, including the famous Joseph Banks who brought more varieties back from China and Japan. Hollyhock – possible origins range from and Syria to India but mostly likely to be natives of China. This statuesque plant worked its way along the Silk Road over many centuries and is first mentioned in English Crossing literature in John Gardiners poem ’Feate of Gardenini’ in 1440. Sweet William – first appeared in English botanist John Gerard’s garden catalogue in 1596 having made their way from mountainous regions of southern Europe, such as the borders Pyrenees and the Carpathians. -

The Exotic World of Carolus Clusius 1526-1609 and a Reconstruction of the Clusius Garden

The Netherlandish humanist Carolus Clusius (Arras 1526- Leiden 1609) is one of the most important European the exotic botanists of the sixteenth century. He is the author of innovative, internationally famous botanical publications, the exotic worldof he introduced exotic plants such as the tulip and potato world of in the Low Countries, and he was advisor of princes and aristocrats in various European countries, professor and director of the Hortus botanicus in Leiden, and central figure in a vast European network of exchanges. Carolus On 4 April 2009 Leiden University, Leiden University Library, The Hortus botanicus and the Scaliger Institute 1526-1609 commemorate the quatercentenary of Clusius’ death with an exhibition The Exotic World of Carolus Clusius 1526-1609 and a reconstruction of the Clusius Garden. Clusius carolus clusius scaliger instituut clusius all3.indd 1 16-03-2009 10:38:21 binnenwerk.qxp 16-3-2009 11:11 Pagina 1 Kleine publicaties van de Leidse Universiteitsbibliotheek Nr. 80 binnenwerk.qxp 16-3-2009 11:12 Pagina 2 binnenwerk.qxp 16-3-2009 11:12 Pagina 3 The Exotic World of Carolus Clusius (1526-1609) Catalogue of an exhibition on the quatercentenary of Clusius’ death, 4 April 2009 Edited by Kasper van Ommen With an introductory essay by Florike Egmond LEIDEN UNIVERSITY LIBRARY LEIDEN 2009 binnenwerk.qxp 16-3-2009 11:12 Pagina 4 ISSN 0921-9293, volume 80 This publication was made possible through generous grants from the Clusiusstichting, Clusius Project, Hortus botanicus and The Scaliger Institute, Leiden. Web version: https://disc.leidenuniv.nl/view/exh.jsp?id=exhubl002 Cover: Jacob de Monte (attributed), Portrait of Carolus Clusius at the age of 59. -

Of the Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation

Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania Vol. 26, No. 1 Bulletin Spring 2014 of the Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation Inside 4 Duets on display 4 Open House 2014 4 William Andrew 4 Illustrated mushroom Archer papers books, part 2 Above right, Tulipe des jardins. Tulipa gesneriana L. [Tulipa gesnerana Linnaeus, Liliaceae], stipple engraving on paper by P. F. Le Grand, 49 × 32.5 cm, after an original by Gerard van Spaendonck (Holland/France, 1746–1822) for his Fleurs Sessinées d’après Nature (Paris, L’Auteur, au Jardin des Plantes, 1801, pl. 4), HI Art accession no. 2078. Below left, Parrot tulips [Tulipa Linnaeus, Liliaceae], watercolor on paper by Rose Pellicano (Italy/United States), 1998, 56 × 42.5 cm, HI Art accession no. 7405. News from the Art Department Duets exhibition opens The inspiration for the exhibition Duets 1746–1822) has done so with the began with two artworks of trumpet subtle tonality of a monochromatic vine, which were created by the stipple engraving and Rose Pellicano 18th-century, German/English artist (Italy/United States) with rich layers Georg Ehret and the contemporary of watercolor. The former inspired Italian artist Marilena Pistoia. Visitors a legion of botanical artists while frequently request to view a selection teaching at the Jardin des Plantes in of the Institute’s collection of 255 Ehret Paris, and the latter, whose work is and 227 Pistoia original paintings. One inspired by French 18th- and 19th- day we displayed side-by-side the two century artists, carries on this tradition paintings (above left and right) and noticed of exhibiting, instructing and inspiring not only the similarity of composition up-and-coming botanical artists. -

Illustrated Natural History

Claudia Swan Illustrated Natural History The rise of printing and the inception of early modern natural history coincided in funda- mental ways, as amply suggested by the works brought together in this exhibition. This essay is concerned with a key area of overlap between the two practices — namely, visualization and illustration. Sixteenth- and seventeenth-century botanical images, anatomical treatises, and maps demonstrate the centrality of visual information in the pursuit of knowledge about the natural world. Early modern natural history was profoundly dependent on and generative of images, many of them replicable by way of print. Prints, like drawings, could enable identifi- cation and, in turn, use or classification of what they represented. Those engaged in medical study, for example, which involved the twin disciplines of botany and anatomy, encouraged the production of images for study and for medical use — pharmaceutical in the case of plants and pathological in the case of bodies. The case of botany is exemplary. The early modern era is often considered synonymous with the “Botanical Renaissance,” an efflorescence of projects and products whose chronology and lines of descent have been amply charted. This renaissance gained momentum toward the end of the fifteenth century, when printed illustrated works took over from manuscript production. During the first half of the sixteenth century the so-called “fathers of German botany” Otto Brunfels, Hieronymus Bock, and Leonhart Fuchs published volumes that consolidated a new mode of studying the plant world, characterized by, among other things, an amplified naturalism in the often copious illustrations that accompanied their texts (see cats. -

Botanical Gardens in the West Indies John Parker: the Botanic Garden of the University of Cambridge Holly H

A Publication of the Foundation for Landscape Studies A Journal of Place Volume ıı | Number ı | Fall 2006 Essay: The Botanical Garden 2 Elizabeth Barlow Rogers: Introduction Fabio Gabari: The Botanical Garden of the University of Pisa Gerda van Uffelen: Hortus Botanicus Leiden Rosie Atkins: Chelsea Physic Garden Nina Antonetti: British Colonial Botanical Gardens in the West Indies John Parker: The Botanic Garden of the University of Cambridge Holly H. Shimizu: United States Botanic Garden Gregory Long: The New York Botanical Garden Mike Maunder: Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden Profile 13 Kim Tripp Exhibition Review 14 Justin Spring: Dutch Watercolors: The Great Age of the Leiden Botanical Garden New York Botanical Garden Book Reviews 18 Elizabeth Barlow Rogers: The Naming of Names: The Search for Order in the World of Plants By Anna Pavord Melanie L. Simo: Henry Shaw’s Victorian Landscapes: The Missouri Botanical Garden and Tower Grove Park By Carol Grove Judith B. Tankard: Maybeck’s Landscapes By Dianne Harris Calendar 22 Contributors 23 Letter from the Editor The Botanical Garden he term ‘globaliza- botanical gardens were plant species was the prima- Because of the botanical Introduction tion’ today has established to facilitate the ry focus of botanical gardens garden’s importance to soci- The Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries widespread cur- propagation and cultivation in former times, the loss of ety, the principal essay in he botanical garden is generally considered a rency. We use of new kinds of food crops species and habitats through this issue of Site/Lines treats Renaissance institution because of the establishment it to describe the and to act as holding opera- ecological destruction is a it as a historical institution in 1534 of gardens in Pisa and Padua specifically Tgrowth of multi-national tions for plants and seeds pressing concern in our as well as a landscape type dedicated to the study of plants. -

The Golden Age of Dutch Colonial Botany and Its Impact on Garden and Herbarium Collections

The Golden Age of Dutch Colonial Botany and its Impact on Garden and Herbarium Collections Pieter Baas Abstract Apothecaries and surgeons aboard the first fleet of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) in 1602 were instructed to collect herbarium specimens and make detailed observations and illustrations of useful and interesting plants during their voyage. Yet it would take three decades before a first botanical account of some plants from Java would materialise, and much longer before the three great Dutch pioneers of Asian tropical botany and servants of VOC, Paul Hermann (Ceylon), Hendrik Adriaan van Rheede tot Drakenstein (Malabar Coast, India), and Georg Everhard Rumphius (Ambon, Indonesia) made their momentous contributions. Hermann’s herbarium collections are currently mainly in London, but with significant subsets in Leiden and Gotha they were the basis of Linnaeus’s Flora Zeylanica. Hortus Malabar- icus, authored by the nobleman-soldier-diplomat cum amateur botanist Rheede re mains a relevant source of ethno-botanical and pharmacognostic information, judged to O by its recent annotated translations into English and Malayalam by K.S. Manilal. In his powerful role in the VOC, Rheede moreover instructed VOC officials in India, Ceylon and the Cape Colony to send seeds and living plants to Dutch botanical gar dens. Herbarium Amboinense by Georg Everard Rumphius, another self-taught bot anist, was recently translated into English and richly annotated by E.M. Beekman and is even of greater significance. It is an inspiration for modern biopharmaceutical stud ies of tropical plants, selected on the basis of historical ethno-botany. These three highlights of Dutch colonial botany would form a basis on which 20th century initia tives such as Flora Malesiana and Plant Resources of South East Asia (PROSEA) still could build. -

Downloaded4.0 License

Nuncius 35 (2020) 20–63 brill.com/nun A Woodblock’s Career Transferring Visual Botanical Knowledge in the Early Modern Low Countries Jessie Wei-Hsuan Chen Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands [email protected] Abstract The Antwerp publishing house Officina Plantiniana was the birthplace of many impor- tant early modern botanical treatises. Throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth cen- turies, the masters of the press commissioned approximately 4,000 botanical wood- blocks to print illustrations for the publications of the three Renaissance botanists – Rembert Dodoens, Carolus Clusius, and Matthias Lobelius. The woodcuts became one of the bases of early modern botanical visual culture, generating and transmitting the understanding of plants throughout the Low Countries and the rest of Europe. The physical blocks, which are preserved at the Museum Plantin-Moretus in Antwerp, thus offer a material perspective into the development of early modern botany. By exam- ining the 108 woodblocks made for Dodoens’ small herbal, the Florum (1568), and the printing history of a selected few, this article shows the ways in which the use of these woodblocks impacted visual botanical knowledge transfer in the early modern period. Keywords woodblocks – early modern botany – knowledge transfer 1 Introduction In Antwerp in 1568, 108 woodblocks with images of ornamental and fragrant flowers were used for the first time to print the illustrations in the book Florum, et coronariarum odoratarumque nonnullarum herbarum historia (referred to as the 1568 Florum in this article).1 Ordered by the printer-publisher Christophe 1 Rembert Dodoens, Florum, et coronariarum odoratarumque nonnullarum herbarum historia (Antwerp: Christophe Plantin, 1568). -

SWAN CV Updated December 2020.Docx 12/21/20 | Cs

SWAN_CV_Updated_December 2020.docx 12/21/20 | cs CURRICULUM VITAE CLAUDIA SWAN AREAS OF EXPERTISE European art, with a focus on the Netherlands in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries; art and science; early modern global encounters; Renaissance and Baroque graphic arts (prints and drawings); the history of collecting and museology; history of the imagination. EDUCATION Ph.D., Art History, 1997 Columbia University New York, NY Dissertation: “Jacques de Gheyn II and the Representation of the Natural World in the Netherlands ca. 1600” Advisor: David Freedberg (Readers: Keith P.F. Moxey, David Rosand, Simon Schama, J.W. Smit) M.A., Art History, 1987 Johns Hopkins University Baltimore, MD Thesis: “The Galleria Giustiniani: eine Lehrschule für die ganze Welt” Advisor: Elizabeth Cropper B.A. cum laude with Honors in Art History, 1986 Barnard College, Columbia University New York, NY Senior thesis: “‘Annals of Crime’: Man among the Monuments” Advisor: David Freedberg EMPLOYMENT Inaugural Mark S. Weil Professor of Early Modern Art 2021- Department of Art History & Archaeology Washington University in St. Louis St. Louis, MO Associate Professor of Art History 2003- Department Chair 2007-2010 Assistant Professor of Art History 1998-2003 Northwestern University Department of Art History Northwestern University, Evanston, IL Assistant Professor of Art History Northern European Renaissance and Baroque Art The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 1996-1998 Instructor Art Humanities: Masterpieces of Western Art Columbia University, New York, NY 1995-1996 Lecturer (for Simon Schama) 17th-Century Dutch Art and Society Columbia University Spring 1995 Research Assistant Rembrandt Research Project Amsterdam 1986 Translator, Dutch-English Meulenhoff-Landshoff; Benjamins; Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam; Simiolus 1986-1991 FELLOWSHIPS AND RESEARCH AWARDS Post-doctoral fellowships and awards (Invited) Senior Fellow, Imaginaria of Force DFG Centre of Advanced Studies Dir. -

Dramatis Personae

Dramatis Personae Florike Egmond and Lu(sLurs Ram6nRamon Laca In this chapter some key figures in the realization of the Libri Picturati German period he was deeply influenced by Protestantism. project are presented, with their backgrounds and relevant connections, Clusius was, partly by necessity, a truly European figure. After his as well as their respective roles in the process. German experience he studied medicine in France with the fish expert Guillaume Rondelet in Montpellier (1551-1554) and later in Charles de Saint Omer Paris, until religious persecutions forced him to leave and return Lord of Dranoutre (or Renouteren) and Moerkerke (1533-1569), also to the Southern Netherlands in 1563. In the role of tutor of a young known as Karel van Sint Omaars or Carolus a divo Odomaro. Saint member of the rich Fugger family Clusius toured Spain and Portugal, Omer was a wealthy nobleman from the Southern Netherlands who doing field work and collecting material for what would turn out to owned an estate and castle at Moerkercke near Bruges as well as be the first national flora in European history. In the course of this farms, mills, various feudal landholdings and rights, and a house in formative period he acquired no less than eight languages and an Bruges itself. extensive knowledge of a wide variety of subjects. During this early His parents josse de Saint Omer and Anne van Praet married in 1525. phase of his life Clusius translated both Dodonaeus's Cruydtboeck The Praet family belonged to the highest circles of the Flemish aris and Garcia da Orta's work on East Indian plants into Latin. -

Flowerbeds and Hothouses: Botany, Gardens, and the Tcirculation of Knowledge in Things Arens, Esther Helena

www.ssoar.info Flowerbeds and hothouses: botany, gardens, and the tcirculation of knowledge in Things Arens, Esther Helena Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Zur Verfügung gestellt in Kooperation mit / provided in cooperation with: GESIS - Leibniz-Institut für Sozialwissenschaften Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Arens, E. H. (2015). Flowerbeds and hothouses: botany, gardens, and the tcirculation of knowledge in Things. Historical Social Research, 40(1), 265-283. https://doi.org/10.12759/hsr.40.2015.1.265-283 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY Lizenz (Namensnennung) zur This document is made available under a CC BY Licence Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden (Attribution). For more Information see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.de Diese Version ist zitierbar unter / This version is citable under: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-419430 Flowerbeds and Hothouses: Botany, Gardens, and the Circulation of Knowledge in Things ∗ Esther Helena Arens Abstract: »Beet und Treibhaus. Botanik, Gärten und die Zirkulation von Ding- wissen«. The development and management of planted spaces in Northwestern Europe in the 17th and 18th centuries depended on the possibilities for circula- tion in the republic of letters of the Dutch golden age. Circulation was accom- panied by questions of managing space, information and “epistemic things” (Rheinberger) for botanists. Against the conceptual backdrop of “circulation” (Raj), “circulatory regimes” (Saunier) and “ensembles of things” (Hahn), this pa- per analyses, first, flowerbeds as a script for managing information that shaped botanical gardens across Europe in Leiden, Uppsala, Coimbra, and as far as Ba- tavia according to Linnaean principles. -

Dutch Flowers Now

© Hollandse Hoogte / ANP Foto Dutch Flowers Now Masterclass Magazine Flower venues Content in this magazine Leeuwarden Groningen Assen Flowers in Flevoland 6 Corso culture in the Netherlands 7 A guide to taking flower selfies in the 8 Netherlands Flower Parade - Vollenhove Tulpenpluktuin - Marknesse Floriade 2022 10 Flower Parade - Sint Jansklooster Lelystad Zwolle Clusius Tulip Vodka 11 Amsterdam <3 Flowers - a work by artist Rem van den 12 Hanneke’s Pluktuin - Biddinghuizen Bosch Floriade - Almere Flower Parade Bollenstreek Haarlem Zomerbloemen Pluktuin - Nes a/d Amstel Bloomeffects 15 Keukenhof - Lisse Flower Parade - Rijnsburg Marie Bee Bloom 15 Mauritshuis - The Hague Utrecht Keukenhof virtual 15 Arnhem Optiflor - Monster Contact information 17 Flower Parade - Lichtenvoorde Floating Flower Parade Varend Corso ‘s-Hertogenbosch Middelburg Flower Parade - Zundert Maastricht 2 3 Flowers in Flevoland The tulip is synonymous with the Netherlands and the (Noordoostpolder), while Helicentre’s flights depart bulb fields in spring attract millions of visitors with from Lelystad Airport, taking a longer route around the their technicolour displays. With more than 5,000 Flevoland region. For those seeking something a little hectares of tulip fields, annual festivals and a host of more sedate, tulpenballonvaart.nl lets you soar over flower-based activities to enjoy, Flevoland is one of the this area in style: on board a hot air balloon. most spectacular regions in the Netherlands to explore the country’s floral landscape and industry. Another attraction during the spring is Tulip Island, an island which takes the form of a tulip flower. In Flevoland is the youngest province in the Netherlands September, Zeewolde local council planted 150,000 and the largest land reclamation project in the world, tulip bulbs there, all of which are primed to bloom in millions of colourful blooms are springing up on land spring to ignite an explosion of colour. -

The Changing Role of Botanic Gardens in the Mediterranean

The changing role of botanic gardens in the Mediterranean Gianniantonio Domina & Cristina Salmeri Orto botanico ed Herbarium Mediterraneum, via Lincoln 2, 90133 Palermo, Italy. Botanical Garden of Padua established in 1545 in its actual seat World Heritage site of UNESCO Source of inspiration for many other gardens in Italy and around Europe Testimony of scientific and cultural significance Integrity Authenticity Botanical Garden of Pisa established in 1543‐1544 by Luca Ghini, with the financial support by Cosimo I de' Medici, Granduca di Toscana, initially near the Convento di San Vito, was moved in the actual seat in 1591 Botanical Garden of Bologna established in 1568, under the proposal by Ulisse Aldrovandi, initially inside the courtyard of the Palazzo Pubblico in the city center, reached the actual seat in 1803. The Hortus Botanicus of Leiden In 1590 the Hortus was founded by the University of Leiden. In 1594 Carolus Clusius (1526‐1609) turned it into a medicinal herb garden. The Hortus botanicus of Leiden is the oldest botanical garden in the Netherlands and located in the historical centre of the city behind the academy building of the Leiden University. Layout of the Montpellier Botanical Garden, the oldest in France, created by Pierre Richier de Belleval in 1593. © Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle. Dist. RMN‐Grand Palais/image du MNHN, Bibliothèque Centrale. Jardin des plantes in Paris was planted by Guy de La Brosse, Louis XIII's physician, in 1635 as a medicinal herb garden. It was originally known as the Jardin du Roi. The botanic garden of the Universidad de Valencia, known as El Botànic, was founded in 1567.