Western Botanical Gardens: History and Evolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Backgrounder: the New York Botanical Garden's Legacy Of

Moore in America: Monumental Sculpture at The New York Botanical Garden May 24 – November 2, 2008 Backgrounder: The New York Botanical Garden’s Legacy of Natural and Designed Landscapes The New York Botanical Garden, a 250-acre site that has been designated a National Historic Landmark, offers a wealth of beautiful landscapes, including a hardwood Forest, ponds, lakes, streams, rolling hills with dramatic rock outcroppings carved by glaciers, and New York City’s only freshwater river, which runs through the heart of the Forest in a magnificent rock gorge. These picturesque natural features have been further enhanced by more than a century of artful plantings, gardens, and landscapes designed by the nation’s leading landscape architects and garden designers. As a result of both its natural and human legacies, the Botanical Garden today offers an exceptional setting for outdoor sculpture. Scenic beauty and stunning natural features Following the New York State Governor’s approval on April 28, 1891, of The New York Botanical Garden Act of Incorporation, a site needed to be selected for the location of this new educational and scientific institution. Selection turned to an undeveloped park in the central Bronx. In 1887, a published description of this area notes, “it would be difficult to do justice to the exquisite loveliness of this tract without seeming to exaggerate…gigantic trees, centuries old, crown these summits, while great moss and ivy-covered rocks project here and there at different heights above the surface of the water, increasing the wildness of the science.” An 1893 newspaper account describes the romantic vistas of an old stone house, snuff mill, and other artifacts of previous land use, while surrounded with “almost every tree known to the American forest in the Northern clime.” The underlying bedrock, dark gray Fordham gneiss, shapes many rock outcrops, rolling hills, and steep slopes, ranging from 20 to 180 feet above sea level. -

University of Oklahoma Graduate College

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE SCIENCE IN THE AMERICAN STYLE, 1700 – 1800 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By ROBYN DAVIS M CMILLIN Norman, Oklahoma 2009 SCIENCE IN THE AMERICAN STYLE, 1700 – 1800 A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY ________________________ Prof. Paul A. Gilje, Chair ________________________ Prof. Catherine E. Kelly ________________________ Prof. Judith S. Lewis ________________________ Prof. Joshua A. Piker ________________________ Prof. R. Richard Hamerla © Copyright by ROBYN DAVIS M CMILLIN 2009 All Rights Reserved. To my excellent and generous teacher, Paul A. Gilje. Thank you. Acknowledgements The only thing greater than the many obligations I incurred during the research and writing of this work is the pleasure that I take in acknowledging those debts. It would have been impossible for me to undertake, much less complete, this project without the support of the institutions and people who helped me along the way. Archival research is the sine qua non of history; mine was funded by numerous grants supporting work in repositories from California to Massachusetts. A Friends Fellowship from the McNeil Center for Early American Studies supported my first year of research in the Philadelphia archives and also immersed me in the intellectual ferment and camaraderie for which the Center is justly renowned. A Dissertation Fellowship from the Gilder Lehrman Institute for American History provided months of support to work in the daunting Manuscript Division of the New York Public Library. The Chandis Securities Fellowship from the Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens brought me to San Marino and gave me entrée to an unequaled library of primary and secondary sources, in one of the most beautiful spots on Earth. -

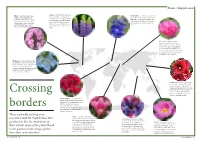

English Roots

Plants / English roots Lupin – cultivated for thousands of Phlox – arrived in Europe from Delphinium – modern day varieties are years, originally as a fodder plant, Virginia, North America in the the result of interbreeding of species from as far apart as ancient Egypt and the early 18th century before crossing many parts of the world, from the Swiss Peruvian Andes. The tall colourful the channel a century later. Many Alps to Siberia. They have been a part of spires popular in English gardens varieties have been bred since not the English garden since at least Tudor have their origin in North American only in England but also in the times. species that arrived in Britain in the Netherlands and United States. 1820s. Rose – the English rose is the result of centuries of breeding of many varieties of rose from around world. One of these is the Damask rose, named after the Syrian city of Damascus, famous for its fragrance. It is thought to have first been brought to England by the Crusaders. Hydrangea – first introduced from Pennsylvania, North America in 1736. In the nineteenth century they became a favourite of plant hunters and botanists, including the famous Joseph Banks who brought more varieties back from China and Japan. Hollyhock – possible origins range from and Syria to India but mostly likely to be natives of China. This statuesque plant worked its way along the Silk Road over many centuries and is first mentioned in English Crossing literature in John Gardiners poem ’Feate of Gardenini’ in 1440. Sweet William – first appeared in English botanist John Gerard’s garden catalogue in 1596 having made their way from mountainous regions of southern Europe, such as the borders Pyrenees and the Carpathians. -

Archival Afterlives: Life, Death, and Knowledge-Making in Early Modern British Scienti C and Medical Archives

Archival Afterlives: Life, Death, and Knowledge-Making in Early Modern British Scienti!"c and Medical Archives Kohn Centre The Royal Society 2 June 2015 Conference Description: Early modern naturalists collected, generated, and shared massive amounts of paper. Inspired by calls for the wholesale reform of natural philosophy and schooled in humanist note-taking practices, they generated correspondence, reading notes (in margins, on scraps, in notebooks), experimental and observational reports, and drafts (rough, partial, fair) of treatises intended for circulation in manuscript or further replication in print. If naturalists claimed all knowledge as their province, natural philosophy was a paper empire. In our own day, naturalists’ materials, ensconced in archives, libraries, and (occasionally) private hands, are now the foundation of a history of science that has taken a material turn towards paper, ink, pen, and !"ling systems as technologies of communication, information management, and knowledge production. Recently, the creation of such papers, and their originators’ organization of them and intentions for them have received much attention. The lives archives lived after their creators’ deaths have been explored less often. The posthumous fortunes of archives are crucial both to their survival as historical sources today and to their use as scienti!"c sources in the past. How did (often) disorderly collections of paper come to be “the archives of the Scienti!"c Revolution”? The proposed conference considers the histories of these papers from the early modern past to the digital present, including collections of material initially assembled by Samuel Hartlib, John Ray, Francis Willughby, Isaac Newton, Hans Sloane, Martin Lister, Edward Lhwyd, Robert Hooke, and Théodore de Mayerne. -

Sources and Bibliography

Sources and Bibliography AMERICAN EDEN David Hosack, Botany, and Medicine in the Garden of the Early Republic Victoria Johnson Liveright | W. W. Norton & Co., 2018 Note: The titles and dates of the historical newspapers and periodicals I have consulted regarding particular events and people appear in the endnotes to AMERICAN EDEN. Manuscript Collections Consulted American Philosophical Society Barton-Delafield Papers Caspar Wistar Papers Catharine Wistar Bache Papers Bache Family Papers David Hosack Correspondence David Hosack Letters and Papers Peale Family Papers Archives nationales de France (Pierrefitte-sur-Seine) Muséum d’histoire naturelle, Série AJ/15 Bristol (England) Archives Sharples Family Papers Columbia University, A.C. Long Health Sciences Center, Archives and Special Collections Trustees’ Minutes, College of Physicians and Surgeons Student Notes on Hosack Lectures, 1815-1828 Columbia University, Rare Book and Manuscript Library Papers of Aaron Burr (27 microfilm reels) Columbia College Records (1750-1861) Buildings and Grounds Collection DeWitt Clinton Papers John Church Hamilton Papers Historical Photograph Collections, Series VII: Buildings and Grounds Trustees’ Minutes, Columbia College 1 Duke University, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library David Hosack Papers Harvard University, Botany Libraries Jane Loring Gray Autograph Collection Historical Society of Pennsylvania Rush Family Papers, Series I: Benjamin Rush Papers Gratz Collection Library of Congress, Washington, DC Thomas Law Papers James Thacher -

Overview of the Dallas Arboretum and Botanical Garden the Mission

Overview of The Dallas Arboretum and Botanical Garden The Mission Our mission makes us much more than just a beautiful place as we are charged to: Provide a place for the art and enjoyment of horticulture Provide for the education of adults and children Provide research to return to the field Do so in a fiscally responsible way 2 DALLAS ARBORETUM The Jonsson Color Garden 3 DALLAS ARBORETUM The Palmer Fern Dell 4 DALLAS ARBORETUM The Paseo de Flores 5 DALLAS ARBORETUM A Woman’s Garden Phase One 6 DALLAS ARBORETUM A Woman’s Garden Phase Two 7 DALLAS ARBORETUM The McCasland Sunken Garden 8 DALLAS ARBORETUM The Boswell Family Garden 9 DALLAS ARBORETUM Nancy’s Garden 10 DALLAS ARBORETUM The Rose Mary Haggar Rose Garden 11 DALLAS ARBORETUM The Nancy Clements Seay Magnolia Glade 12 DALLAS ARBORETUM The Martha Brooks Camellia Garden 13 DALLAS ARBORETUM The Nancy Rutchik Red Maple Rill 14 DALLAS ARBORETUM The Martin Rutchik Concert Stage and Lawn 15 DALLAS ARBORETUM The Lay Family Garden 16 DALLAS ARBORETUM The Henry Lindsley Shadow Garden 17 DALLAS ARBORETUM The Water Wise Garden 18 DALLAS ARBORETUM Artscape, Fine Art Show and Sale 19 DALLAS ARBORETUM A Tasteful Place Opened Fall 2017 A Two and a Half Acre Fruit, Herb, and Vegetable Garden Teaching Visitors How to Grow Local and Sustainable Produce and Cook in Nutritious Ways. Area for tastings or demonstrations each day. An enclosed building for cooking classes and lectures. Four quadrants with plantings in trays that are moved to the greenhouse when dormant. Orchard and vineyard areas. -

Agriculture and the Future of Food: the Role of Botanic Gardens Introduction by Ari Novy, Executive Director, U.S

Agriculture and the Future of Food: The Role of Botanic Gardens Introduction by Ari Novy, Executive Director, U.S. Botanic Garden Ellen Bergfeld, CEO, American Society of Agronomy, Crop Science Society of America, and Soil Science Society of America The more than 320 million Americans alive today depend on plants for our food, clothing, shelter, medicine, and other critical resources. Plants are vital in today’s world just as they were in the lives of the founders of this great nation. Modern agriculture is the cornerstone of human survival and has played extremely important roles in economics, power dynamics, land use, and cultures worldwide. Interpreting the story of agriculture and showcasing its techniques and the crops upon which human life is sustained are critical aspects of teaching people about the usefulness of plants to the wellbeing of humankind. Botanical gardens are ideally situated to bring the fascinating story of American agriculture to the public — a critical need given the lack of exposure to agricultural environments for most Americans today and the great challenges that lie ahead in successfully feeding our growing populations. Based on a meeting of the nation’s leading agricultural and botanical educators organized by the U.S. Botanic Garden, American Society of Agronomy, Crop Science Society of America, and Soil Science Society of America, this document lays out a series of educational narratives that could be utilized by the U.S. Botanic Garden, and other institutions, to connect plants and people through presentation -

Jacksonville Arboretum & Botanical Gardens Receives Grants to Start

Jacksonville Arboretum & Botanical Gardens e-Newsletter February 2021 EDITION Hours: 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. Jacksonville Arboretum & Botanical Gardens Receives Grants to Start Master Plan Process Jacksonville, Fla. (Feb. 10, 2021) – Later this month, the Arboretum will begin the exciting process of developing a master plan to design and install botanical gardens on the property. The master plan process was made possible by generous grants of $30,000 from the Delores Barr Weaver Legacy Fund and $10,000 from the River Branch Foundation. The planning process will take about eight months to complete. The addition of botanical gardens is the latest in a continuous plan to propel the Arboretum into a best-in-class destination in the southeast. Executive Director Dana Doody noted that each project is being planned carefully to add as much value as possible while managing the non-profit’s budget plan in unprecedented times. In addition to the grant for the master plan design, the Delores Barr Weaver Legacy Fund also awarded the Arboretum a $70,000 challenge grant for the first phase of the implementation. The 1:1 challenge grant will launch a community campaign following the completion of the design plan. “The Arboretum is an important community asset which brings thousands of people to its special trails, many of which are ADA accessible,” said Delores Barr Weaver. “The plan will provide a vision for a botanical destination, sure to benefit our citizens for years to come.” The process will take into account the Arboretum’s unique qualities, Florida’s seasons and Jacksonville’s ecosystems and native horticulture. -

Botany in Medieval and Renaissance Universities

Botany in Medieval and Renaissance Universities Karen Meier Reeds Garland Publishing, Inc. New York & London 1991 Contents List of Illustrations Preface Note on Names and Texts 1. The Character of Botany in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance 3 Introduction 3 The Community of Botanists 7 Botany and the Reformation 13 Ancient Sources of Renaissance Botany 14 Looking at Plants 24 Learning from Druggists and Herbalists 24 Emending Classical Texts 26 Drawing Plants from Nature 28 Collecting Plants 33 Conclusion: Anatomy and Botany 36 2. Botany at the University of Montpellier in the Middle Ages and Renaissance 39 Introduction 39 The Study of Simples at the Medieval University 41 The Reformation, Humanism, and the University 47 \ Guillaume Rondelet (1507-1566) and Botany at Montpellier 51 Rondelet's Training as a Doctor and Naturalist 51 Rondelet and Formal Botanical Instruction 56 Rondelet and His Students 63 Botany at Montpellier between Rondelet's Death and Richer de Belleval's Appointment 72 Under Chancellor Antonius Saporta (1566-1573) 72 Under Chancellor Joubertus (1573-1583) 74 Under Chancellor Joannes Hucherus (1583-1603) 78 Pierre Richer de Belleval, Regent Professor of Anatomy and Botany, Founder of the Jardin du Roy at Montpellier 80 Conclusion 91 viii Contents 3. Botany at the University of Basel in the Sixteenth and Early Seventeenth Century 93 Introduction 93 The University Reformers and Botany 96 Paracelsus at Basel (1527) 99 Informal Botanical Activities 104 Books 104 Gardens 106 Ties with Foreign Botanists 108 Formal Botanical Instruction 110 Caspar Bauhin (1560-1624), First Professor of Anatomy and Botany at Basel 111 Early Life and Education 111 Bauhin as a Teacher of Botany 116 Bauhin's Botanical Works 120 Conclusion 130 4. -

An Intergeneric Hybrid Between Franklinia Alatamaha and Gordonia

HORTSCIENCE 41(6):1386–1388. 2006. hybrids using F. alatamaha. Ackerman and Williams (1982) conducted extensive crosses · between F. alatamaha and Camellia L. spp. Gordlinia grandiflora (Theaceae): and produced two intergeneric hybrids, but their growth was weak and extremely slow. An Intergeneric Hybrid Between Ranney and colleagues (2003) reported suc- cessful hybridization between F. alatamaha Franklinia alatamaha and and Schima argentea Pritz. In 1974, Dr. Elwin Orton, Jr. successfully crossed G. lasianthus with F. alatamaha and produced 33 hybrids Gordonia lasianthus (Orton, 1977). Orton (1977) further reported Thomas G. Ranney1,2 that the seedlings grew vigorously during the Department of Horticultural Science, Mountain Horticultural Crops first growing season and that a number of them flowered the following year; however, Research and Extension Center, North Carolina State University, 455 all the plants eventually died, possibly be- Research Dr., Fletcher, NC 28732-9244 cause of some type of genetic incompatibility 1 or a pathogen (e.g., Phytophthora). Although Paul R. Fantz Orton’s report was somewhat discouraging, Department of Horticultural Science, Box 7603, North Carolina State hybridization between F. alatamaha and University, Raleigh, NC 27695-7609 G. lasianthus could potentially combine the cold hardiness of F. alatamaha with the ever- Additional index words. Gordonia alatamaha, Gordonia pubescens, distant hybridization, green foliage of G. lasianthus and broaden intergeneric hybridization, plant breeding, wide hybridization the genetic base for further breeding among Abstract. Franklinia alatamaha Bartr. ex Marshall represents a monotypic genus that was these genera. The objective of this report is originally discovered in Georgia, USA, but is now considered extinct in the wild and is to describe the history of and to validate new maintained only in cultivation. -

51St Annual Spring Plant Sale at the Arboretum’S Red Barn Farm

51st Annual Spring Plant Sale at the Arboretum’s Red Barn Farm Saturday, May 11 and Sunday, May 12, 2019 General Information Table of Contents Saturday , May 11, 9 am to 4 pm Shade Perennials ………………… 2-6 Sunday, May 12, 9 am to 4 pm Ferns………………………………. 6 Sun Perennials……………………. 7-14 • The sale will be held at the Annuals…………………………… 15-17 Arboretum’s Red Barn Farm adjacent to the Annual Grasses……………………17 Tashjian Bee and Pollinator Discovery Center. Enter from 3-mile Drive or directly from 82nd Martagon Lilies…………………... 17-18 Street West. Paeonia (Peony)…………………... 18-19 • No entrance fee if you enter from 82nd Street. Roses………………………………. 20 • Come early for best selection. We do not hold Hosta………………………………. 21-24 back items or restock. Woodies: • Entrances will open at 7:30 if you wish to Vines……………………….. 24 arrive early. No pre-shopping on the sale Trees & Shrubs…………… 24-26 grounds Minnesota Natives………………… 26-27 • Our wagons are always in short supply. Please Ornamental Grasses……………… 27-28 bring carrying containers for your purchases: Herbs………………………………. 29-30 boxes, wagons, carts. Vegetables…………………………. 30-33 • There will be a pickup area where you can drive up to load your plants. • There will be golf carts and shuttles to drive you to and from your vehicle. • Food truck(s) will be on site. Payment • You can assist us in maximizing our The Minnesota Landscape Arboretum support of the MLA by using cash or checks. 3675 Arboretum Drive, Chaska, MN 55318 However, if you wish to use a credit card, we Telephone: 952-443-1400 accept Visa, MasterCard, Amex and Discover. -

Differential Resistance of Gordonieae Trees to Phytophthora Cinnamomi

HORTSCIENCE 44(5):1484–1486. 2009. Successful crosses of Franklinia · Schima produced the intergeneric hybrid ·Schimlinia (Ranney et al., 2003) and crosses of Frank- Differential Resistance of Gordonieae linia · Gordonia produced the intergeneric hybrid ·Gordlinia (Ranney and Fantz, 2006). Trees to Phytophthora cinnamomi However, little is known about the resistance 1 2,5 3 of related species and potential parents to Elisabeth M. Meyer , Thomas G. Ranney , and Thomas A. Eaker P. cinnamomi. The objective of this study Department of Horticultural Science, Mountain Horticultural Crops was to evaluate a collection of species, Research and Extension Center, North Carolina State University, 455 clones, and hybrids of Franklinia, Gordonia, Research Drive, Fletcher, NC 28732 and Schima for resistance to P. cinnamomi. 4 Kelly Ivors Materials and Methods Department of Plant Pathology, Mountain Horticultural Crops Research and Extension Center, North Carolina State University, 455 Research Drive, During the summer of 2008, seven taxa of Gordonieae trees were inoculated with Mills River, NC 28759 P. cinnamomi at the North Carolina State Additional index words. host plant resistance, disease resistance, Abies fraseri, Franklinia University Mountain Horticultural Crops alatamaha, Gordonia lasianthus, ·Gordlinia grandiflora, ·Schimlinia floribunda, Schima Research Station in Mills River, NC. These taxa included F. alatamaha, G. lasianthus, S. wallichii, Schima khasiana, Phytophthora cinnamomi khasiana, S. wallichii, ·Gordlinia H2004- Abstract. Trees in the Theaceae tribe Gordonieae are valuable nursery crops, but some of 024-008, ·Schimlinia H2002-022-083, and these taxa are known to be highly susceptible to root rot caused by Phytophthora ·Schimlinia H2002-022-084. The plants of cinnamomi Rands. The objective of this study was to evaluate a collection of Gordonieae the selected Gordonieae taxa were 5-month- taxa for resistance to this pathogen.