Downloaded4.0 License

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

English Roots

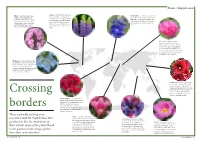

Plants / English roots Lupin – cultivated for thousands of Phlox – arrived in Europe from Delphinium – modern day varieties are years, originally as a fodder plant, Virginia, North America in the the result of interbreeding of species from as far apart as ancient Egypt and the early 18th century before crossing many parts of the world, from the Swiss Peruvian Andes. The tall colourful the channel a century later. Many Alps to Siberia. They have been a part of spires popular in English gardens varieties have been bred since not the English garden since at least Tudor have their origin in North American only in England but also in the times. species that arrived in Britain in the Netherlands and United States. 1820s. Rose – the English rose is the result of centuries of breeding of many varieties of rose from around world. One of these is the Damask rose, named after the Syrian city of Damascus, famous for its fragrance. It is thought to have first been brought to England by the Crusaders. Hydrangea – first introduced from Pennsylvania, North America in 1736. In the nineteenth century they became a favourite of plant hunters and botanists, including the famous Joseph Banks who brought more varieties back from China and Japan. Hollyhock – possible origins range from and Syria to India but mostly likely to be natives of China. This statuesque plant worked its way along the Silk Road over many centuries and is first mentioned in English Crossing literature in John Gardiners poem ’Feate of Gardenini’ in 1440. Sweet William – first appeared in English botanist John Gerard’s garden catalogue in 1596 having made their way from mountainous regions of southern Europe, such as the borders Pyrenees and the Carpathians. -

Gerard's Herbal the OED Defines the Word

Gerard’s Herbal The OED defines the word ‘herbal’ (n) as: ‘a book containing the names and descriptions of herbs, or of plants in general, with their properties and virtues; a treatise in plants.’ Charles Singer, historian of medicine and science, describes herbals as ‘a collection of descriptions of plants usually put together for medical purposes. The term is perhaps now-a-days used most frequently in connection with the finely illustrated works produced by the “fathers of botany” in the fifteenth and sixteenth century.’1 Although the origin of the herbal dates back to ‘remote antiquity’2 the advent of the printing press meant that herbals could be produced in large quantities (in comparison to their earlier manuscript counterparts) with detailed woodcut and metal engraving illustrations. The first herbal printed in Britain was Richard Banckes' Herball of 15253, which was written in plain text. Following Banckes, herbalists such as William Turner and John Gerard gained popularity with their lavishly illustrated herbals. Gerard’s Herbal was originally published in 1597; it is regarded as being one of the best of the printed herbals and is the first herbal to contain an illustration of a potato4. Gerard did Illustration of Gooseberries from not have an enormously interesting life; he was Gerard’s Herbal (1633), demonstrating the intricate detail that ‘apprenticed to Alexander Mason, a surgeon of 5 characterises this text. the Barber–Surgeons' Company’ and probably ‘travelled in Scandinavia and Russia, as he frequently refers to these places in his writing’6. For all his adult life he lived in a tenement with a garden probably belonging to Lord Burghley. -

The Exotic World of Carolus Clusius 1526-1609 and a Reconstruction of the Clusius Garden

The Netherlandish humanist Carolus Clusius (Arras 1526- Leiden 1609) is one of the most important European the exotic botanists of the sixteenth century. He is the author of innovative, internationally famous botanical publications, the exotic worldof he introduced exotic plants such as the tulip and potato world of in the Low Countries, and he was advisor of princes and aristocrats in various European countries, professor and director of the Hortus botanicus in Leiden, and central figure in a vast European network of exchanges. Carolus On 4 April 2009 Leiden University, Leiden University Library, The Hortus botanicus and the Scaliger Institute 1526-1609 commemorate the quatercentenary of Clusius’ death with an exhibition The Exotic World of Carolus Clusius 1526-1609 and a reconstruction of the Clusius Garden. Clusius carolus clusius scaliger instituut clusius all3.indd 1 16-03-2009 10:38:21 binnenwerk.qxp 16-3-2009 11:11 Pagina 1 Kleine publicaties van de Leidse Universiteitsbibliotheek Nr. 80 binnenwerk.qxp 16-3-2009 11:12 Pagina 2 binnenwerk.qxp 16-3-2009 11:12 Pagina 3 The Exotic World of Carolus Clusius (1526-1609) Catalogue of an exhibition on the quatercentenary of Clusius’ death, 4 April 2009 Edited by Kasper van Ommen With an introductory essay by Florike Egmond LEIDEN UNIVERSITY LIBRARY LEIDEN 2009 binnenwerk.qxp 16-3-2009 11:12 Pagina 4 ISSN 0921-9293, volume 80 This publication was made possible through generous grants from the Clusiusstichting, Clusius Project, Hortus botanicus and The Scaliger Institute, Leiden. Web version: https://disc.leidenuniv.nl/view/exh.jsp?id=exhubl002 Cover: Jacob de Monte (attributed), Portrait of Carolus Clusius at the age of 59. -

Colonial Garden Plants

COLONIAL GARD~J~ PLANTS I Flowers Before 1700 The following plants are listed according to the names most commonly used during the colonial period. The botanical name follows for accurate identification. The common name was listed first because many of the people using these lists will have access to or be familiar with that name rather than the botanical name. The botanical names are according to Bailey’s Hortus Second and The Standard Cyclopedia of Horticulture (3, 4). They are not the botanical names used during the colonial period for many of them have changed drastically. We have been very cautious concerning the interpretation of names to see that accuracy is maintained. By using several references spanning almost two hundred years (1, 3, 32, 35) we were able to interpret accurately the names of certain plants. For example, in the earliest works (32, 35), Lark’s Heel is used for Larkspur, also Delphinium. Then in later works the name Larkspur appears with the former in parenthesis. Similarly, the name "Emanies" appears frequently in the earliest books. Finally, one of them (35) lists the name Anemones as a synonym. Some of the names are amusing: "Issop" for Hyssop, "Pum- pions" for Pumpkins, "Mushmillions" for Muskmellons, "Isquou- terquashes" for Squashes, "Cowslips" for Primroses, "Daffadown dillies" for Daffodils. Other names are confusing. Bachelors Button was the name used for Gomphrena globosa, not for Centaurea cyanis as we use it today. Similarly, in the earliest literature, "Marygold" was used for Calendula. Later we begin to see "Pot Marygold" and "Calen- dula" for Calendula, and "Marygold" is reserved for Marigolds. -

HSS Paper 2000

The Many Books of Nature: How Renaissance naturalists created and responded to information overload Brian W. Ogilvie* History of Science Society Annual Meeting, Vancouver, Nov. 3, 2000 Copyright © 2000 Brian W. Ogilvie. All rights reserved. Renaissance natural history emerged in the late fifteenth century at the confluence of humanist textual criticism, the revival of Greek medical texts, and curricular reform in medicine.1 These streams had been set in motion by a deeper tectonic shift: an increasing interest in particular, empirical knowledge among humanists and their pupils, who rejected the scholastic definition of scientific knowledge as certain deductions from universal principles.2 Natural history, which had been seen in antiquity and the Middle Ages as a propaedeutic to natural philosophy or medicine, emerged from this confluence as a distinct discipline with its own set of practitioners, techniques, and norms.3 Ever since Linnaeus, description, nomenclature, and taxonomy have been taken to be the sine qua non of natural history; pre-Linnaean natural history has been treated by many historians as a kind of blind groping toward self-evident principles of binomial nomenclature and encaptic taxa that were first stated clearly by the Swedish naturalist. Today I would like to present a different history. For natural history in the Renaissance, from the late fifteenth through the early seventeenth century, was not a taxonomic * Department of History, Herter Hall, University of Massachusetts, 161 Presidents Drive, Amherst, MA 01003-9312; [email protected]. 2 science. Rather, it was a science of describing, whose goal was a comprehensive catalogue of nature. Botany was at the forefront of that development, for the study of plants had both medical and horticultural applications, but botanists (botanici) rapidly developed interests that went beyond the pharmacy and the garden, to which some scarcely even nodded their heads by 1600. -

Of the Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation

Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania Vol. 26, No. 1 Bulletin Spring 2014 of the Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation Inside 4 Duets on display 4 Open House 2014 4 William Andrew 4 Illustrated mushroom Archer papers books, part 2 Above right, Tulipe des jardins. Tulipa gesneriana L. [Tulipa gesnerana Linnaeus, Liliaceae], stipple engraving on paper by P. F. Le Grand, 49 × 32.5 cm, after an original by Gerard van Spaendonck (Holland/France, 1746–1822) for his Fleurs Sessinées d’après Nature (Paris, L’Auteur, au Jardin des Plantes, 1801, pl. 4), HI Art accession no. 2078. Below left, Parrot tulips [Tulipa Linnaeus, Liliaceae], watercolor on paper by Rose Pellicano (Italy/United States), 1998, 56 × 42.5 cm, HI Art accession no. 7405. News from the Art Department Duets exhibition opens The inspiration for the exhibition Duets 1746–1822) has done so with the began with two artworks of trumpet subtle tonality of a monochromatic vine, which were created by the stipple engraving and Rose Pellicano 18th-century, German/English artist (Italy/United States) with rich layers Georg Ehret and the contemporary of watercolor. The former inspired Italian artist Marilena Pistoia. Visitors a legion of botanical artists while frequently request to view a selection teaching at the Jardin des Plantes in of the Institute’s collection of 255 Ehret Paris, and the latter, whose work is and 227 Pistoia original paintings. One inspired by French 18th- and 19th- day we displayed side-by-side the two century artists, carries on this tradition paintings (above left and right) and noticed of exhibiting, instructing and inspiring not only the similarity of composition up-and-coming botanical artists. -

Illustrated Natural History

Claudia Swan Illustrated Natural History The rise of printing and the inception of early modern natural history coincided in funda- mental ways, as amply suggested by the works brought together in this exhibition. This essay is concerned with a key area of overlap between the two practices — namely, visualization and illustration. Sixteenth- and seventeenth-century botanical images, anatomical treatises, and maps demonstrate the centrality of visual information in the pursuit of knowledge about the natural world. Early modern natural history was profoundly dependent on and generative of images, many of them replicable by way of print. Prints, like drawings, could enable identifi- cation and, in turn, use or classification of what they represented. Those engaged in medical study, for example, which involved the twin disciplines of botany and anatomy, encouraged the production of images for study and for medical use — pharmaceutical in the case of plants and pathological in the case of bodies. The case of botany is exemplary. The early modern era is often considered synonymous with the “Botanical Renaissance,” an efflorescence of projects and products whose chronology and lines of descent have been amply charted. This renaissance gained momentum toward the end of the fifteenth century, when printed illustrated works took over from manuscript production. During the first half of the sixteenth century the so-called “fathers of German botany” Otto Brunfels, Hieronymus Bock, and Leonhart Fuchs published volumes that consolidated a new mode of studying the plant world, characterized by, among other things, an amplified naturalism in the often copious illustrations that accompanied their texts (see cats. -

Botanical Gardens in the West Indies John Parker: the Botanic Garden of the University of Cambridge Holly H

A Publication of the Foundation for Landscape Studies A Journal of Place Volume ıı | Number ı | Fall 2006 Essay: The Botanical Garden 2 Elizabeth Barlow Rogers: Introduction Fabio Gabari: The Botanical Garden of the University of Pisa Gerda van Uffelen: Hortus Botanicus Leiden Rosie Atkins: Chelsea Physic Garden Nina Antonetti: British Colonial Botanical Gardens in the West Indies John Parker: The Botanic Garden of the University of Cambridge Holly H. Shimizu: United States Botanic Garden Gregory Long: The New York Botanical Garden Mike Maunder: Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden Profile 13 Kim Tripp Exhibition Review 14 Justin Spring: Dutch Watercolors: The Great Age of the Leiden Botanical Garden New York Botanical Garden Book Reviews 18 Elizabeth Barlow Rogers: The Naming of Names: The Search for Order in the World of Plants By Anna Pavord Melanie L. Simo: Henry Shaw’s Victorian Landscapes: The Missouri Botanical Garden and Tower Grove Park By Carol Grove Judith B. Tankard: Maybeck’s Landscapes By Dianne Harris Calendar 22 Contributors 23 Letter from the Editor The Botanical Garden he term ‘globaliza- botanical gardens were plant species was the prima- Because of the botanical Introduction tion’ today has established to facilitate the ry focus of botanical gardens garden’s importance to soci- The Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries widespread cur- propagation and cultivation in former times, the loss of ety, the principal essay in he botanical garden is generally considered a rency. We use of new kinds of food crops species and habitats through this issue of Site/Lines treats Renaissance institution because of the establishment it to describe the and to act as holding opera- ecological destruction is a it as a historical institution in 1534 of gardens in Pisa and Padua specifically Tgrowth of multi-national tions for plants and seeds pressing concern in our as well as a landscape type dedicated to the study of plants. -

Foundations of Botany in Western Europe

Chapter 2 Foundations of Botany in Western Europe 1 Europe & the World: Phases & Aspects of Botanical Abstraction The preceding part of this paper (Chaper 1) establishes the material, social and conceptual ground within which the more particular, private and articulate events that concern this chapter may now be considered. Extensive, ongoing plant-selection among peasant populations constitutes a vast experiential ground of anonymous conceptual and technical knowledge lying behind the more articulate levels of horticultural activity, and intellectual exercises in sys- tematics and medicine, and that act as a kind of contextual and constitutive background, observable in the texts of contemporary medical botanists in, say, China or Europe. That, at the least, is the hypothesis advanced in this and the following chapter. The manner in which different vegetative parts come to be identified and individuated for « pharmaceutical » purposes, thus for transmission in relative quantity from place to place, through a series of markets, is itself parasitic, so to speak, on this larger background of intensely used and institutionalised practice. This could be interpreted in terms of the broader knowledge-ground of medical, herbal practice developed continuously through space wherever there are such agrarian populations, or instead in the broader and cogent sense of a dense and extensive experience in commodification processes themselves, whereby a certain manner of generating new object forms suitable for communication across distance (regulated and facilitated by institution and instrument) and suitable for recognition, become graced with certain kinds of reference, description and speech, quantification, thus for fitting into a universally necessary, yet particular kind of knowledge enabling repeated passage between distant places. -

Varia Bibliographica a CLUSIUS VARIANT the Works of Charles De

Varia bibliographica A CLUSIUS VARIANT The works of Charles de 1'Ecluse, or, to give him his Latin name, Carolus Clusius, are well and at length described in the Bibliotheca Belgica (Brussels 1964-1975, vol. 3, pp. 759-784, L89-L98), and by Stephan Aumiiller in his 'Bibliographie und Ikonographie' in the Fest- schrift anläss/ich der -100 idhrigen Wiederkehr der wissenschaftlichen Tàtigkeit von Caro- lus Clusius im pannorzischcn Raum (Eisenstadt 1973, 'Burgenidndische Forschungen' Sonderheft v, pp. 9-92). Both provide lists of libraries in which copies of individual works are known to exist, and with books of such fame and splendour it can safely be assumed that other copies are to be found in many other collections. I have recently been looking at the British Library's holdings of works by Clusius pub- lished in the Low Countries between 1601 and 1621, among them three copies of his Rariorum plantarum historia published by Joannes Moretus at the Officina Plantiniana, Antwerp, 1601. The British Library's General Catalogue of Printed Books describes them as being equal to each other, i.e. the second and third are each called simply 'another copy' of the first. But, as is so often the case, this is not strictly true, and I wonder how many other copies scattered throughout the libraries of the world, not to mention private collec- tions, would show the same or other variations if properly examined. For this work copies are mentioned by the Bibliotheca Belgica at Amsterdam University Library, the Koninklijke Bibliotheek, The Hague, Leiden -

The Golden Age of Dutch Colonial Botany and Its Impact on Garden and Herbarium Collections

The Golden Age of Dutch Colonial Botany and its Impact on Garden and Herbarium Collections Pieter Baas Abstract Apothecaries and surgeons aboard the first fleet of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) in 1602 were instructed to collect herbarium specimens and make detailed observations and illustrations of useful and interesting plants during their voyage. Yet it would take three decades before a first botanical account of some plants from Java would materialise, and much longer before the three great Dutch pioneers of Asian tropical botany and servants of VOC, Paul Hermann (Ceylon), Hendrik Adriaan van Rheede tot Drakenstein (Malabar Coast, India), and Georg Everhard Rumphius (Ambon, Indonesia) made their momentous contributions. Hermann’s herbarium collections are currently mainly in London, but with significant subsets in Leiden and Gotha they were the basis of Linnaeus’s Flora Zeylanica. Hortus Malabar- icus, authored by the nobleman-soldier-diplomat cum amateur botanist Rheede re mains a relevant source of ethno-botanical and pharmacognostic information, judged to O by its recent annotated translations into English and Malayalam by K.S. Manilal. In his powerful role in the VOC, Rheede moreover instructed VOC officials in India, Ceylon and the Cape Colony to send seeds and living plants to Dutch botanical gar dens. Herbarium Amboinense by Georg Everard Rumphius, another self-taught bot anist, was recently translated into English and richly annotated by E.M. Beekman and is even of greater significance. It is an inspiration for modern biopharmaceutical stud ies of tropical plants, selected on the basis of historical ethno-botany. These three highlights of Dutch colonial botany would form a basis on which 20th century initia tives such as Flora Malesiana and Plant Resources of South East Asia (PROSEA) still could build. -

The Project Gutenberg Ebook of the Natural History of Wiltshire, by John Aubrey (#2 in Our Series by John Aubrey)

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Natural History of Wiltshire, by John Aubrey (#2 in our series by John Aubrey) Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this or any other Project Gutenberg eBook. This header should be the first thing seen when viewing this Project Gutenberg file. Please do not remove it. Do not change or edit the header without written permission. Please read the "legal small print," and other information about the eBook and Project Gutenberg at the bottom of this file. Included is important information about your specific rights and restrictions in how the file may be used. You can also find out about how to make a donation to Project Gutenberg, and how to get involved. **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **eBooks Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** *****These eBooks Were Prepared By Thousands of Volunteers!***** Title: The Natural History of Wiltshire Author: John Aubrey Release Date: January, 2004 [EBook #4934] [Yes, we are more than one year ahead of schedule] [This file was first posted on March 31, 2002] [Most recently updated: April 14, 2002] Edition: 10 Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK, THE NATURAL HISTORY OF WILTSHIRE *** This eBook was produced by Mikle Coker. THE NATURAL HISTORY OF WILTSHIRE JOHN AUBREY TO GEORGE POULETT SCROPE, ESQ. M.P., &c, &c. &c. ___________________________________ MY DEAR SIR, BY inscribing this Volume to you I am merely discharging a debt of gratitude and justice.