Botanical Gardens in the West Indies John Parker: the Botanic Garden of the University of Cambridge Holly H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Backgrounder: the New York Botanical Garden's Legacy Of

Moore in America: Monumental Sculpture at The New York Botanical Garden May 24 – November 2, 2008 Backgrounder: The New York Botanical Garden’s Legacy of Natural and Designed Landscapes The New York Botanical Garden, a 250-acre site that has been designated a National Historic Landmark, offers a wealth of beautiful landscapes, including a hardwood Forest, ponds, lakes, streams, rolling hills with dramatic rock outcroppings carved by glaciers, and New York City’s only freshwater river, which runs through the heart of the Forest in a magnificent rock gorge. These picturesque natural features have been further enhanced by more than a century of artful plantings, gardens, and landscapes designed by the nation’s leading landscape architects and garden designers. As a result of both its natural and human legacies, the Botanical Garden today offers an exceptional setting for outdoor sculpture. Scenic beauty and stunning natural features Following the New York State Governor’s approval on April 28, 1891, of The New York Botanical Garden Act of Incorporation, a site needed to be selected for the location of this new educational and scientific institution. Selection turned to an undeveloped park in the central Bronx. In 1887, a published description of this area notes, “it would be difficult to do justice to the exquisite loveliness of this tract without seeming to exaggerate…gigantic trees, centuries old, crown these summits, while great moss and ivy-covered rocks project here and there at different heights above the surface of the water, increasing the wildness of the science.” An 1893 newspaper account describes the romantic vistas of an old stone house, snuff mill, and other artifacts of previous land use, while surrounded with “almost every tree known to the American forest in the Northern clime.” The underlying bedrock, dark gray Fordham gneiss, shapes many rock outcrops, rolling hills, and steep slopes, ranging from 20 to 180 feet above sea level. -

University of Oklahoma Graduate College

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE SCIENCE IN THE AMERICAN STYLE, 1700 – 1800 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By ROBYN DAVIS M CMILLIN Norman, Oklahoma 2009 SCIENCE IN THE AMERICAN STYLE, 1700 – 1800 A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY ________________________ Prof. Paul A. Gilje, Chair ________________________ Prof. Catherine E. Kelly ________________________ Prof. Judith S. Lewis ________________________ Prof. Joshua A. Piker ________________________ Prof. R. Richard Hamerla © Copyright by ROBYN DAVIS M CMILLIN 2009 All Rights Reserved. To my excellent and generous teacher, Paul A. Gilje. Thank you. Acknowledgements The only thing greater than the many obligations I incurred during the research and writing of this work is the pleasure that I take in acknowledging those debts. It would have been impossible for me to undertake, much less complete, this project without the support of the institutions and people who helped me along the way. Archival research is the sine qua non of history; mine was funded by numerous grants supporting work in repositories from California to Massachusetts. A Friends Fellowship from the McNeil Center for Early American Studies supported my first year of research in the Philadelphia archives and also immersed me in the intellectual ferment and camaraderie for which the Center is justly renowned. A Dissertation Fellowship from the Gilder Lehrman Institute for American History provided months of support to work in the daunting Manuscript Division of the New York Public Library. The Chandis Securities Fellowship from the Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens brought me to San Marino and gave me entrée to an unequaled library of primary and secondary sources, in one of the most beautiful spots on Earth. -

English Roots

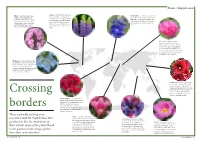

Plants / English roots Lupin – cultivated for thousands of Phlox – arrived in Europe from Delphinium – modern day varieties are years, originally as a fodder plant, Virginia, North America in the the result of interbreeding of species from as far apart as ancient Egypt and the early 18th century before crossing many parts of the world, from the Swiss Peruvian Andes. The tall colourful the channel a century later. Many Alps to Siberia. They have been a part of spires popular in English gardens varieties have been bred since not the English garden since at least Tudor have their origin in North American only in England but also in the times. species that arrived in Britain in the Netherlands and United States. 1820s. Rose – the English rose is the result of centuries of breeding of many varieties of rose from around world. One of these is the Damask rose, named after the Syrian city of Damascus, famous for its fragrance. It is thought to have first been brought to England by the Crusaders. Hydrangea – first introduced from Pennsylvania, North America in 1736. In the nineteenth century they became a favourite of plant hunters and botanists, including the famous Joseph Banks who brought more varieties back from China and Japan. Hollyhock – possible origins range from and Syria to India but mostly likely to be natives of China. This statuesque plant worked its way along the Silk Road over many centuries and is first mentioned in English Crossing literature in John Gardiners poem ’Feate of Gardenini’ in 1440. Sweet William – first appeared in English botanist John Gerard’s garden catalogue in 1596 having made their way from mountainous regions of southern Europe, such as the borders Pyrenees and the Carpathians. -

Leiden, a City Worth Exploring

Dit document wordt u aangeboden door: XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX klik hier voor meer artikelen Leiden, a city worth exploring ‘Seeing is believing’. With this saying in mind, soon becomes obvious when a number of the partici- Leiden Marketing organized the inspirational pants in the weekend is picked up from their hotel by means of battery-powered Tuk-Tuks. The participants weekend ‘Discover the convention city of were dropped off at the Academy building of the Leiden Leiden’. So, late September, more than 20 University for a visit to the Hortus Botanicus Leiden. meeting planners and event organizers from This Hortus dates back to 1590 and this means that it is all over the country came to see with their the oldest Hortus of the Netherlands. Apart from a huge variety of plants that can be admired in various gardens own eyes what Leiden has to offer with regard and hothouses, the site also includes some buildings to corporate events. suited for a corporate meeting, such as the ‘Tuinkamer’ (garden hall) with the Cycas terrace, grand café Clusius Photography Hielco Kuipers with its Curator’s terrace and the Orangery. In grand café Clusius, which can also be leased on an exclu- uring the inspirational weekend a number of sive basis, the food and drinks are provided by caterer Leiden Marketing’s partners is given the op- Vermaat. He uses mainly biological ingredients and Dportunity to present themselves to a dedicated herbs from the gardens. The Orangery from 1744 is group of interested organizers of corporate meetings where the entire group is welcomed by Martijn Bulthuis, and events. -

Sources and Bibliography

Sources and Bibliography AMERICAN EDEN David Hosack, Botany, and Medicine in the Garden of the Early Republic Victoria Johnson Liveright | W. W. Norton & Co., 2018 Note: The titles and dates of the historical newspapers and periodicals I have consulted regarding particular events and people appear in the endnotes to AMERICAN EDEN. Manuscript Collections Consulted American Philosophical Society Barton-Delafield Papers Caspar Wistar Papers Catharine Wistar Bache Papers Bache Family Papers David Hosack Correspondence David Hosack Letters and Papers Peale Family Papers Archives nationales de France (Pierrefitte-sur-Seine) Muséum d’histoire naturelle, Série AJ/15 Bristol (England) Archives Sharples Family Papers Columbia University, A.C. Long Health Sciences Center, Archives and Special Collections Trustees’ Minutes, College of Physicians and Surgeons Student Notes on Hosack Lectures, 1815-1828 Columbia University, Rare Book and Manuscript Library Papers of Aaron Burr (27 microfilm reels) Columbia College Records (1750-1861) Buildings and Grounds Collection DeWitt Clinton Papers John Church Hamilton Papers Historical Photograph Collections, Series VII: Buildings and Grounds Trustees’ Minutes, Columbia College 1 Duke University, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library David Hosack Papers Harvard University, Botany Libraries Jane Loring Gray Autograph Collection Historical Society of Pennsylvania Rush Family Papers, Series I: Benjamin Rush Papers Gratz Collection Library of Congress, Washington, DC Thomas Law Papers James Thacher -

Agriculture and the Future of Food: the Role of Botanic Gardens Introduction by Ari Novy, Executive Director, U.S

Agriculture and the Future of Food: The Role of Botanic Gardens Introduction by Ari Novy, Executive Director, U.S. Botanic Garden Ellen Bergfeld, CEO, American Society of Agronomy, Crop Science Society of America, and Soil Science Society of America The more than 320 million Americans alive today depend on plants for our food, clothing, shelter, medicine, and other critical resources. Plants are vital in today’s world just as they were in the lives of the founders of this great nation. Modern agriculture is the cornerstone of human survival and has played extremely important roles in economics, power dynamics, land use, and cultures worldwide. Interpreting the story of agriculture and showcasing its techniques and the crops upon which human life is sustained are critical aspects of teaching people about the usefulness of plants to the wellbeing of humankind. Botanical gardens are ideally situated to bring the fascinating story of American agriculture to the public — a critical need given the lack of exposure to agricultural environments for most Americans today and the great challenges that lie ahead in successfully feeding our growing populations. Based on a meeting of the nation’s leading agricultural and botanical educators organized by the U.S. Botanic Garden, American Society of Agronomy, Crop Science Society of America, and Soil Science Society of America, this document lays out a series of educational narratives that could be utilized by the U.S. Botanic Garden, and other institutions, to connect plants and people through presentation -

Bibliography Abram - Michell

Landscape Design A Cultural and Architectural History 1 Bibliography Abram - Michell Surveys, Reference Books, Philosophy, and Nikolaus Pevsner. The Penguin Dictionary Nancy, Jean-Luc. Community: The Inoperative Studies in Psychology and the Humanities of Architecture and Landscape Architecture. Community. Edited by Peter Connor. Translated 5th ed. London: Penguin Books, 1998. by Peter Connor, Lisa Garbus, Michael Abram, David. The Spell of the Sensuous: Holland, and Simona Sawhney. Minneapolis: Perception and Language in a More-Than-Human Foucault, Michel. The Order of Being: University of Minnesota Press, 1991. World. New York: Pantheon Books, 1996. An Archaeology of the Human Sciences. Translated by [tk]. New York: Vintage Books, Newton, Norman T. Design on the Land: Ackerman, James S. The Villa: Form and 1994. Originally published as Les Mots The Development of Landscape Architecture. Ideology of Country Houses. Princeton, et les choses (Paris: Gallimard, 1966). Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1971. N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1990. Giedion, Sigfried. Space, Time and Architecture. Ross, Stephanie. What Gardens Mean. Chicago Bachelard, Gaston. The Poetics of Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1967. and London: University of Chicago Press, 1998. Space. Translated by Maria Jolas. Boston: Beacon Press, 1969. Gothein, Marie Luise. Translated by Saudan, Michel, and Sylvia Saudan-Skira. Mrs. Archer-Hind. A History of Garden From Folly to Follies: Discovering the World of Barthes, Roland. The Eiffel Tower and Other Art. New York: E. P. Dutton, 1928. Gardens. New York: Abbeville Press. 1988. Mythologies. Translated by Richard Howard. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1979. Hall, Peter. Cities in Civilization: Schama, Simon. Landscape and Memory. The City as Cultural Crucible. -

Natural Selection: Charles Darwin & Alfred Russel Wallace

Search | Glossary | Home << previous | next > > Natural Selection: Charles Darwin & Alfred Russel Wallace The genius of Darwin (left), the way in which he suddenly turned all of biology upside down in 1859 with the publication of the Origin of Species , can sometimes give the misleading impression that the theory of evolution sprang from his forehead fully formed without any precedent in scientific history. But as earlier chapters in this history have shown, the raw material for Darwin's theory had been known for decades. Geologists and paleontologists had made a compelling case that life had been on Earth for a long time, that it had changed over that time, and that many species had become extinct. At the same time, embryologists and other naturalists studying living animals in the early 1800s had discovered, sometimes unwittingly, much of the A visit to the Galapagos Islands in 1835 helped Darwin best evidence for Darwin's formulate his ideas on natural selection. He found theory. several species of finch adapted to different environmental niches. The finches also differed in beak shape, food source, and how food was captured. Pre-Darwinian ideas about evolution It was Darwin's genius both to show how all this evidence favored the evolution of species from a common ancestor and to offer a plausible mechanism by which life might evolve. Lamarck and others had promoted evolutionary theories, but in order to explain just how life changed, they depended on speculation. Typically, they claimed that evolution was guided by some long-term trend. Lamarck, for example, thought that life strove over time to rise from simple single-celled forms to complex ones. -

The Correspondence of Julius Haast and Joseph Dalton Hooker, 1861-1886

The Correspondence of Julius Haast and Joseph Dalton Hooker, 1861-1886 Sascha Nolden, Simon Nathan & Esme Mildenhall Geoscience Society of New Zealand miscellaneous publication 133H November 2013 Published by the Geoscience Society of New Zealand Inc, 2013 Information on the Society and its publications is given at www.gsnz.org.nz © Copyright Simon Nathan & Sascha Nolden, 2013 Geoscience Society of New Zealand miscellaneous publication 133H ISBN 978-1-877480-29-4 ISSN 2230-4495 (Online) ISSN 2230-4487 (Print) We gratefully acknowledge financial assistance from the Brian Mason Scientific and Technical Trust which has provided financial support for this project. This document is available as a PDF file that can be downloaded from the Geoscience Society website at: http://www.gsnz.org.nz/information/misc-series-i-49.html Bibliographic Reference Nolden, S.; Nathan, S.; Mildenhall, E. 2013: The Correspondence of Julius Haast and Joseph Dalton Hooker, 1861-1886. Geoscience Society of New Zealand miscellaneous publication 133H. 219 pages. The Correspondence of Julius Haast and Joseph Dalton Hooker, 1861-1886 CONTENTS Introduction 3 The Sumner Cave controversy Sources of the Haast-Hooker correspondence Transcription and presentation of the letters Acknowledgements References Calendar of Letters 8 Transcriptions of the Haast-Hooker letters 12 Appendix 1: Undated letter (fragment), ca 1867 208 Appendix 2: Obituary for Sir Julius von Haast 209 Appendix 3: Biographical register of names mentioned in the correspondence 213 Figures Figure 1: Photographs -

Toeristisch Bezoek Aan Leiden in 2010 En Motivering Toeristisch Gebied Leiden)

B&W.nr. 11.0872, d.d. 13 september 2011 Onderwerp Herijking toeristisch gebied a.g.v. de wijziging in winkeltijdenwet per 01.01.2011 Besluiten: 1. de notitie ‘Herijking toeristisch gebied gemeente Leiden’ voor inspraak vast te stellen, waarin drie beleidsvarianten voor het toeristisch gebied – in de zin van de winkeltijdenwet – worden overwogen: a. de binnenstad en het stationsdistrict (handhaving huidige situatie) b. geheel Leiden (uitbreiding), c. geen (afschaffen van de huidige situatie), 2. de verslaglegging van de raadpleging van stadspartners over dit onderwerp vast te stellen, 3. in afwijking van artikel 7 van de Inspraakverordening de termijn van de inspraak te stellen op vier weken, ingaande de maandag, volgende op de besluitdatum van dit besluit; Perssamenvatting: De winkeltijdenwet uit 1996 is gewijzigd per 1 januari 2011. Op grond van die wijziging, zijn gemeenten, die een toeristisch gebied in de zin van de winkeltijdenwet hebben aangewezen, verplicht die aanwijzing te herijken. De gemeente moet onderbouwen waarom de gemeente daadwerkelijk toeristisch is. De toeristische aantrekkingskracht dient autonoom en substantieel te zijn. De wet geeft aan welke verplichte (belangen)afweging gemaakt moet worden: a. werkgelegenheid en economische bedrijvigheid in de gemeente, waaronder mede wordt begrepen het belang van winkeliers met weinig of geen personeel en van winkelpersoneel; b. de zondagsrust in de gemeente; c. de leefbaarheid, de veiligheid en de openbare orde in de gemeente. In de Notitie ‘Herijking toeristisch gebied gemeente Leiden’ wordt deze afweging gemaakt. Deze notitie wordt voor inspraak vastgesteld. Na verwerking van de inspraakreacties zal het college van Burgemeester en wethouders de raad voorstellen uit de drie beleidsvarianten met bijbehorende varianten winkeltijdenverordeningen, er één te kiezen. -

The Exotic World of Carolus Clusius 1526-1609 and a Reconstruction of the Clusius Garden

The Netherlandish humanist Carolus Clusius (Arras 1526- Leiden 1609) is one of the most important European the exotic botanists of the sixteenth century. He is the author of innovative, internationally famous botanical publications, the exotic worldof he introduced exotic plants such as the tulip and potato world of in the Low Countries, and he was advisor of princes and aristocrats in various European countries, professor and director of the Hortus botanicus in Leiden, and central figure in a vast European network of exchanges. Carolus On 4 April 2009 Leiden University, Leiden University Library, The Hortus botanicus and the Scaliger Institute 1526-1609 commemorate the quatercentenary of Clusius’ death with an exhibition The Exotic World of Carolus Clusius 1526-1609 and a reconstruction of the Clusius Garden. Clusius carolus clusius scaliger instituut clusius all3.indd 1 16-03-2009 10:38:21 binnenwerk.qxp 16-3-2009 11:11 Pagina 1 Kleine publicaties van de Leidse Universiteitsbibliotheek Nr. 80 binnenwerk.qxp 16-3-2009 11:12 Pagina 2 binnenwerk.qxp 16-3-2009 11:12 Pagina 3 The Exotic World of Carolus Clusius (1526-1609) Catalogue of an exhibition on the quatercentenary of Clusius’ death, 4 April 2009 Edited by Kasper van Ommen With an introductory essay by Florike Egmond LEIDEN UNIVERSITY LIBRARY LEIDEN 2009 binnenwerk.qxp 16-3-2009 11:12 Pagina 4 ISSN 0921-9293, volume 80 This publication was made possible through generous grants from the Clusiusstichting, Clusius Project, Hortus botanicus and The Scaliger Institute, Leiden. Web version: https://disc.leidenuniv.nl/view/exh.jsp?id=exhubl002 Cover: Jacob de Monte (attributed), Portrait of Carolus Clusius at the age of 59. -

PART II PERSONAL PAPERS and ORGANIZATIONAL RECORDS Allen, Paul Hamilton, 1911-1963 Collection 1 RG 4/1/5/15 Photographs, 1937-1959 (1.0 Linear Feet)

PART II PERSONAL PAPERS AND ORGANIZATIONAL RECORDS Allen, Paul Hamilton, 1911-1963 Collection 1 RG 4/1/5/15 Photographs, 1937-1959 (1.0 linear feet) Paul Allen was a botanist and plantsman of the American tropics. He was student assistant to C. W. Dodge, the Garden's mycologist, and collector for the Missouri Botanical Garden expedition to Panama in 1934. As manager of the Garden's tropical research station in Balboa, Panama, from 1936 to 1939, he actively col- lected plants for the Flora of Panama. He was the representative of the Garden in Central America, 1940-43, and was recruited after the War to write treatments for the Flora of Panama. The photos consist of 1125 negatives and contact prints of plant taxa, including habitat photos, herbarium specimens, and close-ups arranged in alphabetical order by genus and species. A handwritten inventory by the donor in the collection file lists each item including 19 rolls of film of plant communities in El Salvador, Costa Rica, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Panama. The collection contains 203 color slides of plants in Panama, other parts of Central America, and North Borneo. Also included are black and white snapshots of Panama, 1937-1944, and specimen photos presented to the Garden's herbarium. Allen's field books and other papers that may give further identification are housed at the Hunt Institute of Botanical Documentation. Copies of certain field notebooks and specimen books are in the herbarium curator correspondence of Robert Woodson, (Collection 1, RG 4/1/1/3). Gift, 1983-1990. ARRANGEMENT: 1) Photographs of Central American plants, no date; 2) Slides, 1947-1959; 3) Black and White photos, 1937-44.