[Bombarde How To] Downloading

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2014 (Mise À Jour 8 Janvier 2014)

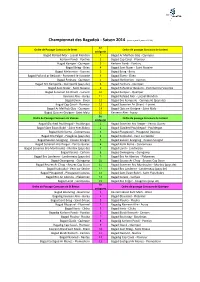

Championnat des Bagadoù ‐ Saison 2014 (mise à jour 8 janvier 2014) 1e Ordre de Passage Concours de Brest Ordre de passage Concours de Lorient catégorie Bagad Roñsed Mor ‐ Locoal Mendon 1 Bagad Ar Meilhoù Glaz ‐ Quimper Kerlenn Pondi ‐ Pontivy 2 Bagad Cap Caval ‐ Plomeur Bagad Kemper ‐ Quimper 3 Kerlenn Pondi ‐ Pontivy Bagad Brieg ‐ Briec 4 Bagad Sant Nazer ‐ Saint Nazaire Bagad Melinerion ‐ Vannes 5 Bagad Brieg ‐ Briec Bagad Pañvrid ar Beskont ‐ Pommerit le Vicomte 6 Bagad Elven ‐ Elven Bagad Penhars ‐ Quimper 7 Bagad Melinerion ‐ Vannes Bagad Bro Kemperle ‐ Quimperlé (pays de) 8 Bagad Penhars ‐ Quimper Bagad Sant Nazer ‐ Saint Nazaire 9 Bagad Pañvrid ar Beskont ‐ Pommerit le Vicomte Bagad Sonerien An Oriant ‐ Lorient 10 Bagad Kemper ‐ Quimper Kevrenn Alre ‐ Auray 11 Bagad Roñsed Mor ‐ Locoal Mendon Bagad Elven ‐ Elven 12 Bagad Bro Kemperle ‐ Quimperlé (pays de) Bagad Cap Caval ‐ Plomeur 13 Bagad Sonerien An Oriant ‐ Lorient Bagad Ar Meilhoù Glaz ‐ Quimper 14 Bagad Quic en Groigne ‐ Saint Malo Bagad Quic en Groigne ‐ Saint Malo 15 Kevrenn Alre ‐ Auray 2e Ordre de Passage Concours de Vannes Ordre de passage Concours de Lorient catégorie Bagad Glaziked Pouldregad ‐ Pouldergat 1 Bagad Sonerien Bro Dreger ‐ Perros Guirec Bagad Sant Ewan Bubri ‐ Saint Yves Bubry 2 Bagad Glaziked Pouldregad ‐ Pouldergat Bagad Konk Kerne ‐ Concarneau 3 Bagad Plougastell ‐ Plougastel Daoulas Bagad Bro Felger ‐ Fougères (pays de) 4 Bagad Kadoudal ‐ Vern sur Seiche Bagad Saozon‐Sevigneg ‐ Cesson Sevigné 5 Bagad Saozon‐Sevigneg ‐ Cesson Sevigné Bagad Sonerien Bro -

Les Nouvelles N° 35

LE MAGAZINE D’INFORMATION DE LORIENT AGGLOMÉRATION JUILLET-AOÛT 2017 N°35 SUPPLÉMENT BIENVENUE à la NOUVELLE GARE Le sens de l'accueil P.18 Aux petits soins du littoral P.26 Les bagadoù, c'est tendance ! DANS VOTRE MAGAZINE Pratique JUILLET-AOÛT 2017 Maison de l’Agglomération, 02 I SOMMAIRE / ÉDITO Esplanade du Péristyle à Lorient. 04 I ARRÊT SUR IMAGE Tél. 02 90 74 71 00 Accueil et standard ouverts du lundi au vendredi 06 I OBJECTIF AGGLO de 8h30 à 17h30. www.lorient-agglo.bzh TERRE Collecte et tri des déchets 10 I TOURISME 0 800 100 601 > LE TOURISME 2.0 Du lundi au vendredi de 8h30 à 12h et de 13h30 à 17h. 16 I AÉROPORT > APRÈS PORO, CAP SUR LONDRES Eau potable, assainissement 17 I PORTRAIT 0 800 100 601 > UN HOMME DU RAIL Lundi de 8h30 à 17h15, du mardi au jeudi de 8h30 à 12h15 et de 13h30 à 17h15, vendredi de 8h30 à 16h30. MER Espace info habitat 18 I LITTORAL 0 800 100 601 > UNE CÔTE SOUS HAUTE SURVEILLANCE Service public gratuit proposé par Lorient Agglomération 24 I ENVIRONNEMENT et regroupant le service Habitat, l’ADIL (information > L’EAU, À CONSOMMER AVEC MODÉRATION logement) et l’Espace Info Energie d’ALOEN. 25 I PORTRAIT > PLANCHE À VOILE : GRAINE DE CHAMPION L’EIH accompagne les nouveaux arrivants et les habitants souhaitant louer, rénover, acheter ou construire un logement. HOMMES Espace Info Habitat, esplanade du Péristyle, quartier de l’Enclos du port à Lorient, à côté de la Maison de l’Agglo- 26 I CULTURE mération. -

Practices and Perceptions Around Breton As a Regional Language Of

New speaker language and identity: Practices and perceptions around Breton as a regional language of France Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Merryn Davies-Deacon B.A., M.A. February, 2020 School of Arts, English, and Languages Abstract This thesis focuses on the lexicon of Breton, a minoritised Celtic language traditionally spoken in western Brittany, in north-west France. For the past thirty years, much work on Breton has highlighted various apparent differences between two groups of speak- ers, roughly equivalent to the categories of new speakers and traditional speakers that have emerged more universally in more recent work. In the case of Breton, the concep- tualisation of these two categories entails a number of linguistic and non-linguistic ste- reotypes; one of the most salient concerns the lexicon, specifically issues around newer and more technical vocabulary. Traditional speakers are said to use French borrowings in such cases, influenced by the dominance of French in the wider environment, while new speakers are portrayed as eschewing these in favour of a “purer” form of Breton, which instead more closely reflects the language’s membership of the Celtic family, in- volving in particular the use of neologisms based on existing Breton roots. This thesis interrogates this stereotypical divide by focusing on the language of new speakers in particular, examining language used in the media, a context where new speakers are likely to be highly represented. The bulk of the analysis presented in this work refers to a corpus of Breton gathered from media sources, comprising radio broadcasts, social media and print publications. -

Practices and Perceptions Around Breton As a Regional Language of France

DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY New speaker language and identity: Practices and perceptions around Breton as a regional language of France Davies-Deacon, Merryn Award date: 2020 Awarding institution: Queen's University Belfast Link to publication Terms of use All those accessing thesis content in Queen’s University Belfast Research Portal are subject to the following terms and conditions of use • Copyright is subject to the Copyright, Designs and Patent Act 1988, or as modified by any successor legislation • Copyright and moral rights for thesis content are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners • A copy of a thesis may be downloaded for personal non-commercial research/study without the need for permission or charge • Distribution or reproduction of thesis content in any format is not permitted without the permission of the copyright holder • When citing this work, full bibliographic details should be supplied, including the author, title, awarding institution and date of thesis Take down policy A thesis can be removed from the Research Portal if there has been a breach of copyright, or a similarly robust reason. If you believe this document breaches copyright, or there is sufficient cause to take down, please contact us, citing details. Email: [email protected] Supplementary materials Where possible, we endeavour to provide supplementary materials to theses. This may include video, audio and other types of files. We endeavour to capture all content and upload as part of the Pure record for each thesis. Note, it may not be possible in all instances to convert analogue formats to usable digital formats for some supplementary materials. -

Sound Diplomacy Is the Leading Global Music Export Agency

SOUND DIPLOMACY IS THE LEADING GLOBAL MUSIC EXPORT AGENCY Sound Diplomacy is a multi‑lingual export, research and event production consultancy based in CONSULTING London, Barcelona and Berlin. Export Strategizing We draw on over thirty years of Planning & Development creative industries experience Brand Management to deliver event and conference Workshop Coordination coordination, world‑class research, Market Research export strategy and market & Analysis intelligence to both the public and Teaching & Strategic private sector. Consulting We have over 30 clients in 4 continents, including government ministries, music and cultural EVENT export offices, music festivals and SERVICES conferences, universities and more. Conference We work simultaneously in seven Management languages (English, Spanish, Event Production Catalan, German, French, Greek, Coordination Danish). & Logistics SOUND DIPLOMACY ACTIVE EVENTS FRENCH STUDY 1. INTRODUCTION The French music market has both French and Breton: traditional music with a modern twist. decreased in the last decade: Tangui Le Cras (Les Vieilles Charrues, Krismenn) states from €662 million in 2007 down to there is a small market for folk music in France though €363.7 in 2012. this is very much anchored in Breton, and therefore very competitive due to the amount of domestic content from the region. According to him, Folk music from Northern According to SNEP (Syndicat National de l’Edition Europe is more difficult to work in a world music context Phonographique), the digital music market has been where -

Du Pérou Aux Émirats Arabes Un Bagad, Ça Voyage !

N° ISSN 0999-1948 - 4 euros R ONER N°A 397 - Juillet 2017 S Au cœur de la musique bretonne Audience record au Quartz Du Pérou aux Émirats Karaez, Brest arabes 70 ans aussi un bagad, ça voyage ! Des pistes pour Labo scolaire pour bagad Juillet 2017 - Sonerion - Ar Soner n° 397 financer son projet 1 En images Edito Les gagnants du jeu Sonerion PAR ANDRÉ QUEFFELEC Fédération nationale PRÉSIDENT DE SONERION Dans le n° 396, Ar Soner Centre Amzer Nevez 2, chemin du Conservatoire proposait un jeu-concours 56270 Ploemeur autour de l’exposition Tél : 02 97 86 05 54 La pratique CONCOURS «Sonerion, une extraordinaire Dépôt légal - 1er trimestre 2017 aventure» qui retrace les 70 ans ISSN 0999-1948 amateur de la fédération. Directeur de publication : enfin Neuf bonnes réponses nous sont André Queffelec parvenues. Un tirage au sort, Chef de rédaction : reconnue Béatrice Mingam le 30 mai dernier, a désigné les Les 15 et 16 avril, 38 stagiaires ont participé à un Rédaction : quatre gagnants. Aucun lot ne stage de batterie écossaise au siège de Sonerion à Béatrice Mingam n décret publié le 10 mai 2017, la veille de la passation de pouvoir présidentiel, sera expédié, ils sont à retirer à : Amzer Nevez (Ploemeur) dans le Morbihan. Quatre sauf mentions contraires Uvient clore le débat sur la présence des artistes amateurs et des groupements Sonerion, Centre Amzer Nevez, enseignants sont intervenus. Ancien penn batteur Participations : d’artistes amateurs dans les représentations artistiques : l’issueun d’ combat de 12 2 chemin du Conservatoire, du Bagad Cap Caval, en Ecosse depuis 2007, fina- André Queffelec, Tanguy Baudet, années auquel Sonerion aura pleinement participé. -

See Program 2019

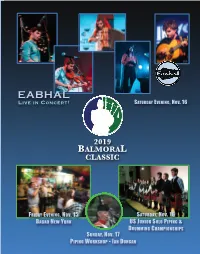

Program_Cover_Classic2019_Rv2.qxp_Program 11/4/19 5:18 PM Page 1 EABHAL L IVEIN CONCERT ! SATURDAY EVENING, NOV. 16 2019 Balmoral School, Pittsburgh Session Our 2019 Instructors were Andrew Carlisle, Bruce Gandy, Jimmy Bell, Gordon Bell, Richmond Johnston, Colin Bell, George Balderose and others. The Balmoral School of Piping and Drumming 2020 SUMMER SCHEDULE: PITTSBURGH JULY 5-10, EAST STROUDSBURG JULY 12-17 2020 Guest Instructors To Be Announced By Jan. 1 2019 BALMORAL Immerse yourself for a week on one of CLASSIC our beautiful campuses with some of the best pipers and pipe band drummers in the world. Receive intensive personal instruction, workshops, music sessions, presentations on piping and drumming topics, while making friendships that can last a lifetime. For More Information Contact: FRIDAY EVENING, NOV. 15 SATURDAY, N OV. 16 Balmoral School of Piping and Drumming BAGAD NEW YORK US J UNIOR SOLO PIPING & 1414 Pennsylvania Avenue, Pittsburgh, PA 15233 (412) 323-2707 DRUMMING CHAMPIONSHIPS SUNDAY, NOV. 17 [email protected] www.bagpiping.org PIPING WORKSHOP - IAN DUNCAN America’s annual bagpiping celebration BALMORAL CLASSICWWW.BALMORALCLASSIC 2019.ORG FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 15 Celtic culture celebration kicks off at 7:30pm with performances by renowned pipers and drummers, our judges for the next day’s Championships. At 9:00pm we are joined by Bagad New York for Breton music and dance. Dances will be taught, no partner necessary. Co-sponsored with BalFolk Pittsburgh. 7:30-11:00pm | Tickets: $5 | Wyndham Pittsburgh University Center(WPUC), 100 Lytton Ave, Pittsburgh SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 16 United States Junior Solo Bagpiping & Snare Drumming Championships. Piping contest in Frick Fine Arts Auditorium; Drumming contest in Carnegie Lecture Hall 8:30am-4:30pm | Free | Frick Fine Arts Auditorium (FFA) & Carnegie Lecture Hall (CLH), Pittsburgh/Oakland SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 16 Concert: Acclaimed Scottish band, Eabhal, to be joined by Scottish and Irish dancers. -

NOTING the TRADITION an Oral History Project from the National Piping Centre

NOTING THE TRADITION An Oral History Project from the National Piping Centre Interviewee Jean Charles Beauverger Interviewer Angus MacKay Date of Interview 24 th October 2012 This interview is copyright of the National Piping Centre Please refer to the Noting the Tradition Project Manager at the National Piping Centre, prior to any broadcast of or publication from this document. Project Manager Noting The Tradition The National Piping Centre 30-34 McPhater Street Glasgow G4 0HW [email protected] Copyright The National Piping Centre 2012 So, I’ll just start, just now. I am Angus MacKay and I am speaking with Jean Charles Beauverger. I am in Glasgow and Jean Charles, where are you at the moment? I am right now in Mol, in Belgium, it is in the France part of Belgium. Okay. And, it is the 27th of November and I am just going to ask you a little bit about your experiences in bagpiping, so, I mean, first of all, can you tell me how you got into piping? I started, I was about twenty years old, so I did not came from a family who plays the bagpipes but my family was a bit related to Breton culture. I went to Boy Scouts group in Quimper and this Boy Scout group, there is a bagad so I do not know if you are familiar with this term, bagad? No. Can you tell me what it means? So, principle it is kind of Breton version of the pipe band, so it is a band where you put together Highland bagpipes, then the drums as it is in the pipe band added to that you put the bombarde which is, kind of, typical Breton instrument who is traditionally played with Breton bagpipes, so at the end you have a quite large band, similar to pipe bands in the boy scout group, they have this kind of band, so firstly I joined the group for the Scouts and then I had the opportunity to start this instrument. -

Celebration De La Saint Yves a New York

INTERCELTIC FEST NOZ IN TIMES SQUARE Saturday January 30th : a celebration of music, dance, and culture of Brittany, Galicia, Ireland, Scotland and Wales. New York, January 26. BZH New York has organized the first Interceltic Fest Noz which will take place in New York on Saturday, January 30, 2010 at Connolly’s Times Square. The Fest Noz is a celebration of music, dance, and culture of Brittany, Galicia, Ireland, Scotland and Wales and will feature 40 musicians from the 5 Celtic nations, dance sets from the different Celtic cultures and a silent auction. In addition, the evening will celebrate the Celtic festival of Imbolc. Imbolc is one of the four principal festivals celebrated among Celtic peoples, either at the beginning of February or at the first local signs of Spring. The current lineup of performers includes the following: Bretagne: Duo Morgane Labbe and Francois Tiger - Bagad de New York - Marie Martin Ireland: Washington Square Harp and Shamrock Orchestra Led - Tony DeMarco and Friends - Niall O'Leary School of Irish Dance Scotland: Wild Thistle featuring Mary Morrisson Abdill and Hannah Maire Marcus – Aodhagán - Capital Region Celtic Pipe Band, Wales: Honey and Biscuits featuring Helen Ellis and Mary Morrisson Galicia: Nosa Terra Silent auction from 7pm to 10pm: Artists Capucine Bourcart and Christophe LeGris will auction 6 photographies with all proceeds going to Action Against Hunger and its Relief Efforts in Haiti. Event details : Saturday January 30th 2010, 7PM to 2AM Connolly's Pub Restaurant (Klub 45, 3rd floor) 121 West -

SECTION II – RECORDINGS of BRETON MUSIC – Notes and Reviews Newsletter/Bro Nevez 1 (1981) to 86 (May 2003)

SECTION II – RECORDINGS OF BRETON MUSIC – Notes and Reviews Newsletter/Bro Nevez 1 (1981) to 86 (May 2003) Recordings - general guides and lists 'Discography for Breton harp,' "The revival of the Celtic harp in Brittany" Lois Kuter. 4/5, August/November 1982: 38-39. "How to find Breton records" Lois Kuter. 28, November 1988:3. "A selection of Breton records" 28, November 1988:4-5. Recording labels / Distributors / Stores “Gwerz Pladenn musicians … on the road” (L. Kuter). 56, November 1995:22. “Coop Breizh – making Breton music accessible” (Coop Breizh/L. Kuter). 56, November 1995:23-26. ‘Congratulations to Jakez Le Soueff,’ “A few more short notes” (L. Kuter). 60, November 1996:11. ‘The Coop Breizh turns 30,’ “Short notes – what’s happening in Brittany” (L. Kuter). 61, Februiary 1997:6. “The Coop Breizh (1957-1997)—At the Heart of Breton culture for 40 years” (Coop Breizh, L. Kuter, transl.). 64, November 1997:15-19. “The Keltia Musique recording label celebrates 20 years” (L. Kuter). 67, August 1998:24. Short Notes about Specific Recordings (alphabetical by artist) Abjean, Rene, Pol & Herve Queffeleant, Job an Irien. War varc'h d'ar mor. 1996. "Heard of but not heard" Lois Kuter. 59, August 1996:21. Accordéons diatoniques en Bretagne. 1990. "Music: new recordings" (L. Kuter). 35, August 1990:25. Accordéon en Haute Bretagne. 1996. "Heard of but not heard" Lois Kuter. 59, August 1996:21. Accordéons en Haute-Bretagne. 1999. “New recordings – heard of, but not heard” (L. Kuter). 70, May 1999:24. l'Air du Temps. De Ouip en Ouap. 1993. "Record notes" Lois Kuter. -

Breton – an Endangered Language of Europe

ã International Committee for the Defense of the Breton Language Breton – an endangered language The Romans invaded Brittany in the first century BC. of Europe The Celts fought them but were defeated. The Roman presence in Brittany was peaceful and this was a period th th By Lois Kuter, Secretary for the U.S. Branch of the when roads and towns were built. During the 5 and 6 International Committee for the Defense of the Breton century especially, but also before this, there was a Language (U.S. ICDBL). [email protected] great deal of travel between Celtic peoples in Britain and Armorica – especially by early Christians who were This is a modification of a presentation given to a class both spiritual and political leaders. The shift to the name on Endangered Languages at the University of Brittany bears witness to this travel. Kentucky, Linguistics Program, March 30, 2004. It was published in Bro Nevez No. 90, May 2004. Please do This is a complicated period with settlement of a great not quite or copy materials from this article without the number of Celts from Wales, Cornwall and Devon, as permission of the author. The views expressed in this well as Ireland, in Brittany. This was a period of uneasy article are those of the author and do not necessarily relations between the Francs (French) and Bretons. th th represent ICDBL philosophy or policy. During the 5 to 7 centuries there was constant warfare on the borderlands which are now roughly the same as the present day border between Brittany and The Breton Language is a Celtic Language France. -

Invités Sonneurs Danseurs

6 7 Le Festival Presqu’île Breizh remercie ses partenaires QUIBERON Quiberon 26-27-28 Octobre 2018 Vendredi 26 octobre SAINT PIERRE QUIBERON 1 Port d’Orange: Ouverture du festival Les îles 5 Invités 20h00 Feu d’artifice 20h15 - 22h30 Sandie Geffroy - Guillaume Quéré 11 800 Melven 4 9 Sonneurs SAUZON et 2 Port de Sauzon 20h00 Feu d’artifice 13 2 1 20h15 - 22h30 Fest Noz 10 Danseurs 3 Yann et Stéphane KERMABON Tanguy JEGOU 12 Feux d’Artifice Gratuit 8 17 18 22 27 Programme détaillé sur 21 14 20 Presqu’île Breizh 25 19 www.presquilebreizh.bzh 23 24 26 Avec le soutien de MAIRIE 56170 - Ile de Houat 15 [email protected] Hôtel du Phare Sauzon +33 2 97 30 68 04 Impression et mise en page : www.acmquiberon.fr - Ne pas jeter sur la voie publique SAINT PIERRE QUIBERON QUIBERON Dimanche 28 octobre 8 Grand Rohu 14 Esplanade Hoche - Grande Scène SAINT PIERRE QUIBERON 14h15 - 15h00 Dañserien Ruiz - Noyalo 11h30 - 12h00 A.C Donaire da Coruña - La Corogne 13 Place des Martyrs de Penthièvre 9 Portivy Galice - Espagne 11h00 - 11h45 Bagad Sonerien Lann-Bihoué - Baden 14h30 - 15h15 Bagad Cap Caval - Plomeur 15 Pointe du Conguel 13 Eglise Saint Pierre 10 Keridenvel 14h00 - 14h45 Bagad de Vannes Melinerion & bagadig 17h00 - 18h00 Académie de musique et d’arts sacrés 14h30 - 15h15 Cercle celtique Danserien 16 Esplanade Hoche - Marché Saint Anne d’Auray Ar Vro Pourlet Le Croisty 14h30 - 15h00 Kadoudal Drum & Bugle Corps - Quiberon Concert Orgue et bombarde 11 Kerhostin 17 Kerniscob 14h30 - 15h15 Lorient Pipe Band Brittany 14h30 - 15h15 Cercle Celtique