“Like Sugar in Milk”: Reconstructing the Genetic History of the Parsi Population

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyright by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani 2012

Copyright by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani 2012 The Dissertation Committee for Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Princes, Diwans and Merchants: Education and Reform in Colonial India Committee: _____________________ Gail Minault, Supervisor _____________________ Cynthia Talbot _____________________ William Roger Louis _____________________ Janet Davis _____________________ Douglas Haynes Princes, Diwans and Merchants: Education and Reform in Colonial India by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2012 For my parents Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without help from mentors, friends and family. I want to start by thanking my advisor Gail Minault for providing feedback and encouragement through the research and writing process. Cynthia Talbot’s comments have helped me in presenting my research to a wider audience and polishing my work. Gail Minault, Cynthia Talbot and William Roger Louis have been instrumental in my development as a historian since the earliest days of graduate school. I want to thank Janet Davis and Douglas Haynes for agreeing to serve on my committee. I am especially grateful to Doug Haynes as he has provided valuable feedback and guided my project despite having no affiliation with the University of Texas. I want to thank the History Department at UT-Austin for a graduate fellowship that facilitated by research trips to the United Kingdom and India. The Dora Bonham research and travel grant helped me carry out my pre-dissertation research. -

On the Good Faith

On the Good Faith Zoroastrianism is ascribed to the teachings of the legendary prophet Zarathustra and originated in ancient times. It was developed within the area populated by the Iranian peoples, and following the Arab conquest, it formed into a diaspora. In modern Russia it has evolved since the end of the Soviet era. It has become an attractive object of cultural produc- tion due to its association with Oriental philosophies and religions and its rearticulation since the modern era in Europe. The lasting appeal of Zoroastrianism evidenced by centuries of book pub- lishing in Russia was enlivened in the 1990s. A new, religious, and even occult dimension was introduced with the appearance of neo-Zoroastrian groups with their own publications and online websites (dedicated to Zoroastrianism). This study focuses on the intersectional relationships and topical analysis of different Zoroastrian themes in modern Russia. On the Good Faith A Fourfold Discursive Construction of Zoroastrianism in Contemporary Russia Anna Tessmann Anna Tessmann Södertörns högskola SE-141 89 Huddinge [email protected] www.sh.se/publications On the Good Faith A Fourfold Discursive Construction of Zoroastrianism in Contemporary Russia Anna Tessmann Södertörns högskola 2012 Södertörns högskola SE-141 89 Huddinge www.sh.se/publications Cover Image: Anna Tessmann Cover Design: Jonathan Robson Layout: Jonathan Robson & Per Lindblom Printed by E-print, Stockholm 2012 Södertörn Doctoral Dissertations 68 ISSN 1652-7399 ISBN 978-91-86069-50-6 Avhandlingar utgivna vid -

605-616 Hinduism and Zoroastrianism.Indd

Hinduism and Zoroastrianism The term “Zoroastrianism,” coined in the 19th migrated to other parts of the world, and in the century in a colonial context, is inspired by a postcolonial age, especially since the 1960s, this Greek pseudo-etymological rendering (Zoro- movement has intensified, so that the so-called astres, where the second element is reminiscent diaspora is becoming the key factor for the future of the word for star) of the ancient Iranian name development of the religion (Stausberg, 2002b; Zaraϑuštra (etymology unclear apart from the sec- Hinnells, 2005). Given their tiny numbers, their ond element, uštra [camel]). This modern name non-proselytization and their constructive con- of the religion reflects the emphasis on Zarathus- tributions to Indian society (e.g. example through tra (Zoroaster) as its (presumed) founding figure their various charitable contributions [Hinnells, or prophet. 2000]), and their commitments to the army and Zoroastrianism and Hinduism share a remote other Indian institutions, which are routinely common original ancestry, but their historical celebrated in community publications, the Parsis trajectories over the millennia have been notably and their religion have so far not drawn forth any distinct. Just like Hinduism claims and maintains negative social response in India. a particular relationship to the spatial entity know Being offshoots of older Indo-European and as India, Zoroastrianism has conceived itself as Indo-Iranian poetic traditions, the oldest tex- the religion of the Iranians and -

Summer/June 2014

AMORDAD – SHEHREVER- MEHER 1383 AY (SHENSHAI) FEZANA JOURNAL FEZANA TABESTAN 1383 AY 3752 Z VOL. 28, No 2 SUMMER/JUNE 2014 ● SUMMER/JUNE 2014 Tir–Amordad–ShehreverJOUR 1383 AY (Fasli) • Behman–Spendarmad 1383 AY Fravardin 1384 (Shenshai) •N Spendarmad 1383 AY Fravardin–ArdibeheshtAL 1384 AY (Kadimi) Zoroastrians of Central Asia PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA Copyright ©2014 Federation of Zoroastrian Associations of North America • • With 'Best Compfiments from rrhe Incorporated fJTustees of the Zoroastrian Charity :Funds of :J{ongl(pnffi Canton & Macao • • PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA Vol 28 No 2 June / Summer 2014, Tabestan 1383 AY 3752 Z 92 Zoroastrianism and 90 The Death of Iranian Religions in Yazdegerd III at Merv Ancient Armenia 15 Was Central Asia the Ancient Home of 74 Letters from Sogdian the Aryan Nation & Zoroastrians at the Zoroastrian Religion ? Eastern Crosssroads 02 Editorials 42 Some Reflections on Furniture Of Sogdians And Zoroastrianism in Sogdiana Other Central Asians In 11 FEZANA AGM 2014 - Seattle and Bactria China 13 Zoroastrians of Central 49 Understanding Central 78 Kazakhstan Interfaith Asia Genesis of This Issue Asian Zoroastrianism Activities: Zoroastrian Through Sogdian Art Forms 22 Evidence from Archeology Participation and Art 55 Iranian Themes in the 80 Balkh: The Holy Land Afrasyab Paintings in the 31 Parthian Zoroastrians at Hall of Ambassadors 87 Is There A Zoroastrian Nisa Revival In Present Day 61 The Zoroastrain Bone Tajikistan? 34 "Zoroastrian Traces" In Boxes of Chorasmia and Two Ancient Sites In Sogdiana 98 Treasures of the Silk Road Bactria And Sogdiana: Takhti Sangin And Sarazm 66 Zoroastrian Funerary 102 Personal Profile Beliefs And Practices As Shown On The Tomb 104 Books and Arts Editor in Chief: Dolly Dastoor, editor(@)fezana.org AMORDAD SHEHREVER MEHER 1383 AY (SHENSHAI) FEZANA JOURNAL FEZANA Technical Assistant: Coomi Gazdar TABESTAN 1383 AY 3752 Z VOL. -

Growth of Parsi Population India: Demographic Perspectives

Unisa et al Demographic Predicament of Parsis in India Sayeed Unisa, R.B.Bhagat, and T.K.Roy International Institute for Population Sciences, Mumbai, India Email: [email protected] www.iipsindia.org Paper presented at XXVI IUSSP International Population Conference 27 September to 2 October 2009 Marrakech 1 Unisa et al Demographic Predicament of Parsis in India Sayeed Unisa, R.B.Bhagat, and T.K.Roy International Institute for Population Sciences, Mumbai E-mail: [email protected] The Parsi community in India is perhaps the only community outside Europe to have experienced dramatic population and fertility decline. This indicates that a country that is experiencing high population growth can also have communities that have different kinds of demographic patterns. Parsis are a small but prosperous religious community that maintained some sort of social isolation by practising endogamy and not accepting any new converts to their faith. Their population started declining since 1941 and the explanations that are put forth pertain to the issues of under- enumeration, fertility decline and emigration. In this paper, the relative importance of these factors in the light of 2001 Census is examined. This study demonstrates that the unprecedented fall in fertility among Parsis is the prime contributor to its declining population size. Also in this paper, the population of Parsis is projected up to the year 2051. 2 Unisa et al INTRODUCTION Parsis are perhaps the only community which had experienced dramatic population and fertility decline outside Europe (Coale, 1973; Coale and Watkin, 1986). This indicates that in a country that is experiencing high population growth can also have communities, which amazingly have different kinds of demographic pattern (Axelrod, 1990; Lorimer, 1954). -

A Study of Dehzado Records of the 1881 Census of Baroda State

Article Sociological Bulletin Population, Ethnicity 66(1) 1–21 © 2017 Indian Sociological Society and Locality: A Study of SAGE Publications sagepub.in/home.nav Dehzado Records of the DOI: 10.1177/0038022916688286 1881 Census of Baroda http://journals.sagepub.com/home/sob State A.M. Shah1 Lancy Lobo2 Shashikant Kumar3 USE Abstract At the Census of India, 1881, the former princely state of Baroda published data for every village and town, called Dehzado. After presenting the general demo- graphy of Baroda state, this article presents an analysis of data on caste, tribe and religion. It provides classification of villages and towns by the number of castes and tribes found in them, and discusses the issues posed by them, especially the issue of single-caste villages. This article describes the horizontal spread of various castes, tribes and religiousCOMMERCIAL minorities and points out its implications. In the end, it discusses the problem of urbanisation, classifying the towns by ethnic groups found in them. FOR Keywords Baroda state, caste, Census of India, Dehzado, demography, Gujarat, religion, rural–urban relations,NOT tribe Introduction This is a work in historical sociology of the former princely state of Baroda in Gujarat, based on records of the Census of 1881. These are printed records in Gujarati, known as Dehzado (Persian deh = village; zado = people). They are 1 Archana, Arpita Nagar, Subhanpura Road, Race Course, Vadodara, Gujarat, India. 2 Director, Centre for Culture and Development, Vadodara, Gujarat, India. 3 Director, Green Eminent, Novino-Tarsali Road, Tarsali, Vadodara, Gujarat, India. Corresponding author: Lancy Lobo, Centre for Culture and Development, Sevasi Post, Vadodara – 301101, Gujarat, India. -

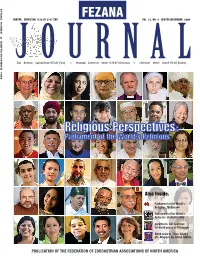

FEZANA Journal Do Not Necessarily Reflect the Views of FEZANA Or Members of This Publication's Editorial Board

FEZANA JOURNAL FEZANA WINTER ZEMESTAN 1378 AY 3747 ZRE VOL. 23, NO. 4 WINTER/DECEMBER 2009 G WINTER/DECEMBER 2009 JOURNALJODae – Behman – Spendarmad 1378 AY (Fasli) G Amordad – Shehrever – Meher 1379 AY (Shenshai) G Shehrever – Meher – Avan 1379 AY (Kadimi) Also Inside: Parliament oof the World’s Religions, Melbourne Parliamentt oof the World’s Religions:Religions: A shortshort hihistorystory Zarathustiss join in prayers for world peace in Pittsburgh Book revieew:w Thus Spake the Magavvs by Silloo Mehta PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA afezanajournal-winter2009-v15 page1-46.qxp 11/2/2009 5:01 PM Page 1 PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA Vol 23 No 4 Winter / December 2009 Zemestan 1378 AY - 3747 ZRE President Bomi V Patel www.fezana.org Editor in Chief: Dolly Dastoor 2 Editorial [email protected] Technical Assistant: Coomi Gazdar Dolly Dastoor Assistant to Editor Dinyar Patel Consultant Editor: Lylah M. Alphonse, 4ss Coming Event [email protected] Graphic & Layout: Shahrokh Khanizadeh, www.khanizadeh.info Cover design: Feroza Fitch, 5 FEZANA Update [email protected] Publications Chair: Behram Pastakia Columnists: 16 Parliament of the World’s Religions Hoshang Shroff: [email protected] Shazneen Rabadi Gandhi : [email protected] Yezdi Godiwalla [email protected] Behram Panthaki: [email protected] 47 In the News Behram Pastakia: [email protected] Mahrukh Motafram: [email protected] Copy editors: R Mehta, V Canteenwalla -

The Shaping of Modern Gujarat

A probing took beyond Hindutva to get to the heart of Gujarat THE SHAPING OF MODERN Many aspects of mortem Gujarati society and polity appear pulling. A society which for centuries absorbed diverse people today appears insular and patochiai, and while it is one of the most prosperous slates in India, a fifth of its population lives below the poverty line. J Drawing on academic and scholarly sources, autobiographies, G U ARAT letters, literature and folksongs, Achyut Yagnik and Such Lira Strath attempt to Understand and explain these paradoxes, t hey trace the 2 a 6 :E e o n d i n a U t V a n y history of Gujarat from the time of the Indus Valley civilization, when Gujarati society came to be a synthesis of diverse peoples and cultures, to the state's encounters with the Turks, Marathas and the Portuguese t which sowed the seeds ol communal disharmony. Taking a closer look at the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the authors explore the political tensions, social dynamics and economic forces thal contributed to making the state what it is today, the impact of the British policies; the process of industrialization and urbanization^ and the rise of the middle class; the emergence of the idea of '5wadeshi“; the coming £ G and hr and his attempts to transform society and politics by bringing together diverse Gujarati cultural sources; and the series of communal riots that rocked Gujarat even as the state was consumed by nationalist fervour. With Independence and statehood, the government encouraged a new model of development, which marginalized Dai its, Adivasis and minorities even further. -

Syllabus BBA BCA Sem-4 EC202 History of Gujarat and Its Culture

Elective Course EC-202(5) HISTORY OF GUJARAT AND ITS CULTURE Course Introduction: The course would make students know about the history of ancient Gujarat and its magnificent heritage. It also discusses about the people who have contributed in respective fields and have increased the glory of Gujarat. The course will give the student a feel of having pilgrimage around Gujarat. Objectives: The student would be able to: 1) To get familiar with various sculptures and monuments of Gujarat. 2) Brief knowledge of different Rulers periods like maurya, maitrak as well as some well known folks. 3) To learn about varieties in culture and life style of people in Gujarat. No. of Credits: 2 Theory Sessions per week: 2 Teaching Hours: 20 hours UNIT TOPICS / SUBTOPICS 1 Gujarat’s Geography • The Historicity of Ancient Gujarat: o The brief history of Gujarat, Lothal, Dholavira, Dwarka and Somnath o Maurya period and Gujarat Chandragupt maurya, About Girinagar, Bindu Sarovar, Ashok, Vikramaditya. o Shak - kshatraps period and Gujarat Sudarshan talav o Gupta period and Gujarat o Maitrak period and Gujarat (Valabhipur) o Gurjar – Pratihar period and Gujarat (Post-Maitrak period) o Chavda period and Gujarat Jayshikhari, Vanraj, Yogaraj, Samantsinh and Mularaj. o Solanki period and Gujarat The invasion of Gaznavi on somnath, Bhimdev, Karandeo, Minaldevi, Siddharaj,kumarpal, Bhimdev-second. o Vaghela period and Guajrat o Pragvats and naagars, Vastupal, Tejpal, Karanghelo, Vishaldev 2 The Glittering Lamps, Geography of Gujarat • Gujarat’s Geography : Location, Latitude, Longitude, Rivers, Mountains, Environment. • The Glittering Lamps Mahatma Gandhiji, Narsinh Mehta, Meera, Premanand,Narmad, Zaverchand Meghani, Tana Riri, Baiju Bawara, Avinash Vyas, Praful Dave, Ravishankar Raval, Homai Vyarawala, Mrinalini Sarabhai, Kumudini Lakhia, Dr. -

The Parsi Dilemma: a New Zealand Perspective

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ResearchArchive at Victoria University of Wellington The Parsi Dilemma: A New Zealand Perspective By David John Weaver A thesis submitted to Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Asian Studies Victoria University of Wellington 2012 i Contents Abstract ii Preface iii Glossary vi Abbreviations vii Part 1 Orientation Chapter 1 Introduction 1 2 A Brief History of the Parsi Community in India 16 3 The Parsi Community in New Zealand and Diaspora comparisons 30 Part 2 Parsi Identity Chapter 4 Individualism and the Parsi Community 40 5 The Impact of Religion on the Parsi Identity 49 6 Social and Economic Factors and the Parsi Community 59 Part 3 Individuality and the Future for Parsis in New Zealand and World-wide; A New Zealand Perspective Chapter 7 Individualism 73 Chapter 8 Possible Future Directions 96 Part 4 Conclusions Chapter 9 Overview 105 10 Conclusions 109 Appendix A Interview Questions 115 Bibliography 117 ii Abstract The Parsis of India are a very small but important ethnic group, traditionally living in Gujarat but in modern times mainly located in Bombay, where, under the British Raj, they established themselves as leading merchants, politicians and professional people with an influence far exceeding their numerical strength. Since Indian Independence in 1947, that influence has declined as has the total size of the Parsi community in India. Many members of the community have dispersed overseas and during the last twenty years, New Zealand has emerged as a growing destination of choice. -

Facebook Like: Parsi Times SATURDAY, AUGUST 02, 2014 P.T

SATURDAY, AUGUST 02, 2014 VOL. 4 - ISSUE 15 :: PAGES 20 :: ` 2/- RNI NO. MAHBIL/2011/39373 Regn. No. MH/MR/South-348/2012-14 WWW.PARSI-TIMES.COM Prince of Persia Pg. 04 Kanga & Khusrokhan Speak Pg. 06 Yuppie For Guppy Full Power Family > Pg. 05 Opera 7 Parsis > Pg. 11 Pg. 10 Prof. Arceivala speaks The World This Week about ecology to Pg. 13 the WZCC Mumbai Chapter > Pg. 09 FaceBook Like: Parsi Times SATURDAY, AUGUST 02, 2014 P.T. will now be delivered to your doorstep fresh and early, Saturday morning from Depots ĂĐƌŽƐƐDĂŚĂƌĂƐŚƚƌĂĂŶĚ'ƵũĂƌĂƚ͘ZĞůĂƟǀĞƐĞǀĞƌLJǁŚĞƌĞĐĂŶƌĞĂĚǁŝƚŚLJŽƵ͊dĂůŬƚŽŚĞĂƌ 02 ƌĞŐƵůĂƌWĂƉĞƌǁĂůůĂĂŶĚĐŽŶŶĞĐƚǁŝƚŚƵƐĂƚ;ϬϮϮͿϲϲϯϯϬϰϬϰĨŽƌŵŽƌĞŝŶĨŽƌŵĂƟŽŶ͘ Editorial RELIGIOUS ANNOUNCEMENTS Dear Readers, Salgreh Jashan &RPHFHOHEUDWHWKH6DOJUHKRIWKH'DG\VHWK2OG3DN Most wrongs that wHÀJKWWRFRUUHFWRUPRVWFDXVHVWKDWZHVWDQGXSIRU $WDVK%HKUDPRQWKHWK$XJXVW0RQGD\ KDYHDGLUHFWUHODWLRQVKLSWRWKHHYHQWVDQGFLUFXPVWDQFHVLQRXUOLYHV,IZH 0RUQLQJ-DVKDQDWDPDQGDP KDYH6SHFLDO&KLOGUHQDWKRPHZHÀJKWIRUWKHLUULJKWVLQ6RFLHW\LIZHKDYH (YHQLQJ-DVKDQDWSPDQGSP UHODWLYHVZLWK&DQFHUZHOHQGRXUYRLFHVWRWKHQHHGIRU0HGLFDOUHVHDUFKDQG VRRQDQGVRIRUWK,WLVYHU\UDUHO\WKDWVRPHRQHZKRLVEOHVVHGZLWKDQXQFRPSOLFDWHGOLIHÀJKWV v$pv$ui¡W$ Q¡fuV$u V²$õV$ IRURUVWDQGVXSIRUVRPHWKLQJELJJHUWKDQMXVWKLVRUKHUEHLQJ:KLOHWKLVLVWKHQRUPWKHUHDUH v$pv$ui¡W$“p ‘yfpZp ‘pL$ Apsi Apsibl¡fpd kpl¡b“u 232du iyc PDQ\IDEXORXVH[FHSWLRQVWRWKHUXOH kpgN°¡l L$v$du fp¡S> 17dp¡ kfp¡i eTv$ dpl 1gp¡ afp¡M afhv$}“ eTv$ +RZHYHUEHLQJXQFRPSOLFDWHGDQGKDYLQJDVLPSOHOLIHGRHVQRWJLYHDQ\RQHWKHULJKWWRWDLQW 1384 e.T. il¡“iplu fp¡S> 22dp¡ Np¡hpv$ eTv$ -

Zoroastrianism in India, by Jesse S. Palsetia

CHAPTER SEVEN Zoroastrianism in India JESSE S . P ALSETI A Introduction HE PARSIS ARE A community in India that trace their ancestry T and religious identity to pre-Islamic, Zoroastrian Iran (pre-651 CE). Te Parsis presently number approximately 110,000 individuals worldwide, and 57,245 individu als in India according to the Census of India 2011. Tis chapter examines the history of the Parsis and the emergence of a unique religious community in India. Te Parsis are the descendants of the Zoroastrians of Iran who migrated to and settled in India in order to preserve their religion. Zoroastrianism is the religion associated with the teachings and revelation of the Iranian prophet and priest Zarathustra (or Zoroaster, as he was referred to by the ancient Greeks). Zarathustra and his religious message date from the second millennium BCE (c. 1200-1000 BCE). Zoroastrianism was the first major religion of Iran and a living faith in the an cient world. Zoroastrianism shares with Hindu (Vedic) religion ancient roots in the common history of the Indo-Iranian peoples. Te oldest Zoroastrian religious works are the Gāthās: a collection of esoteric songs, poems, and thoughts composed in Old Iranian, later referred to as Gāthic Avestan or Old Avestan, and ascribed to Zarathustra and his culture. Te Gāthās intimate a world of good and evil attributed to antagonistic good and evil spirits. Zoro- astrianism represents an original attempt to unify the existing ancient Iranian dualistic tradition within an ethical framework. Early Zoro- astrianism held human nature to be essentially good, and modern Zoroastrianism continues to summarize the duty of humans as 226 JESSE S .