The Parsi Dilemma: a New Zealand Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyright by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani 2012

Copyright by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani 2012 The Dissertation Committee for Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Princes, Diwans and Merchants: Education and Reform in Colonial India Committee: _____________________ Gail Minault, Supervisor _____________________ Cynthia Talbot _____________________ William Roger Louis _____________________ Janet Davis _____________________ Douglas Haynes Princes, Diwans and Merchants: Education and Reform in Colonial India by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2012 For my parents Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without help from mentors, friends and family. I want to start by thanking my advisor Gail Minault for providing feedback and encouragement through the research and writing process. Cynthia Talbot’s comments have helped me in presenting my research to a wider audience and polishing my work. Gail Minault, Cynthia Talbot and William Roger Louis have been instrumental in my development as a historian since the earliest days of graduate school. I want to thank Janet Davis and Douglas Haynes for agreeing to serve on my committee. I am especially grateful to Doug Haynes as he has provided valuable feedback and guided my project despite having no affiliation with the University of Texas. I want to thank the History Department at UT-Austin for a graduate fellowship that facilitated by research trips to the United Kingdom and India. The Dora Bonham research and travel grant helped me carry out my pre-dissertation research. -

RTR-IV-Annual-Report

ZOROASTRIAN RETURN TO ROOTS ZOROASTRIAN RETURN TO ROOTS Welcome 3 Acknowledgements 4 About 8 Vision 8 The Fellows 9 Management Team 30 Return: 2017 Trip Summary 36 Revive: Ongoing Success 59 Donors 60 RTR Annual Report - 2017 WELCOME From 22nd December 2017 - 2nd January 2018, 25 young Zoroastrians from the diaspora made a journey to return, reconnect, and revive their Zoroastrian roots. This was the fourth trip run by the Return to Roots program and the largest in terms of group size. Started in 2012 by a small group of passionate volunteers, and supported by Parzor, the inaugural journey was held from December 2013 to January 2014 to coincide with the World Zoroastrian Congress in Bombay, India. The success of the trips is apparent not only in the transformational experiences of the participants but the overwhelming support of the community. This report will provide the details of that success and the plans for the program’s growth. We hope that after reading these pages you will feel as inspired and motivated to act as we have. Sincerely, The Zoroastrian Return to Roots Team, 2017 3 RTR Annual Report - 2017 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS As we look back on four successful trips of Return to Roots, we are reminded, now more than ever, of the countless people who have lent their support and their time to make sure that the youth on each of these trips have an unforgettable experience. All we can offer to those many volunteers and believers who have built this program is our grateful thanks and the hope that reward comes most meaningfully in its success. -

Parsi Zarathushtis

FEZA FEZANA NA PAIZ 1382 AY 3751 Z VOL. 27, NO. 3 OCTOBER/FALL 2013 JOU R NA L ● OC TOBER/FA LL 2 JOUMehr – Avan – Adar 1382 AY (Fasli) ● Ardebehesht – KhordadRN – Tir 1383 AY (Shenha i) ● Khordad – TirAL – Amordad 1383 AY (Kadimi) 013 ADDENDUM ADDRESS DEMOGRAPHIC CONCERNS IN NORTH AMERICA The Zarathushti World — 2012 Demographic Picture: The Numbers Game Also Inside: Cyrus Cylinder Celebrated in Chicago Tanya Bharda’s Journey in India ZOI Camp Kids’ “Lookie” Stand Presentation of FEZANA Strategic Plan PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA Copyright ©2013 Federation of Zoroastrian Associations of North America FEZANA Journal FALL 2013 ADDENDUM The declining demographics of the Zarathushti world is of major concern to all. Acknowledging the problem and identifying its extent and ramifications was the first step which was articulated in the FALL 2013 issue of the FEZANA Journal. More importantly what do we need to do to reverse the trend or at least to stabilize or stop its rapid decline. A cross section of the North American Zarathushti population was surveyed for their opinion: first generation, next generation, intermarried, intra married, young, old, male, female, Iranian Zarathushtis, Parsi Zarathushtis. We received a plethora of information, laments as well as creative thoughts. Cognizant of the fact that by adding all this information to the printed issue would increase the printing and mailing costs when our subscriptions are declining we are trying a new hybrid approach. We are placing on the FEZANA website (www.fezana.org ) the addendum Part 1 containing the contributions of 34 First generation Zarathushtis and Part 2 containing the contributions of 34 next generation Zarathushtis . -

On the Good Faith

On the Good Faith Zoroastrianism is ascribed to the teachings of the legendary prophet Zarathustra and originated in ancient times. It was developed within the area populated by the Iranian peoples, and following the Arab conquest, it formed into a diaspora. In modern Russia it has evolved since the end of the Soviet era. It has become an attractive object of cultural produc- tion due to its association with Oriental philosophies and religions and its rearticulation since the modern era in Europe. The lasting appeal of Zoroastrianism evidenced by centuries of book pub- lishing in Russia was enlivened in the 1990s. A new, religious, and even occult dimension was introduced with the appearance of neo-Zoroastrian groups with their own publications and online websites (dedicated to Zoroastrianism). This study focuses on the intersectional relationships and topical analysis of different Zoroastrian themes in modern Russia. On the Good Faith A Fourfold Discursive Construction of Zoroastrianism in Contemporary Russia Anna Tessmann Anna Tessmann Södertörns högskola SE-141 89 Huddinge [email protected] www.sh.se/publications On the Good Faith A Fourfold Discursive Construction of Zoroastrianism in Contemporary Russia Anna Tessmann Södertörns högskola 2012 Södertörns högskola SE-141 89 Huddinge www.sh.se/publications Cover Image: Anna Tessmann Cover Design: Jonathan Robson Layout: Jonathan Robson & Per Lindblom Printed by E-print, Stockholm 2012 Södertörn Doctoral Dissertations 68 ISSN 1652-7399 ISBN 978-91-86069-50-6 Avhandlingar utgivna vid -

(Dakhma) in Iran (A Case Study of Zoroastrian's Towe

Bagh- e Nazar, 15 (61): 57-70 / Jul. 2018 DOI: 10.22034/bagh.2018.63865 Persian translation of this paper entitled: راهبردی نظری برای باززنده سازی دخمه های زرتشتیان در ایران (نمونۀ موردی : دخمۀ زرتشتیان کرمان) is also published in this issue of journal. A Theoretical Approach to Restoration of Zoroastrian’s Tower of Silence (Dakhma) in Iran (A Case study of Zoroastrian’s tower of silence of Kerman) Mansour Khajepour*1, Zeinab Raoufi2 1. M. A. in Restoration of historical buildings & fabrics, Academic staff member, faculty of Art and Architecture, Shahid Bahonar University of Kerman. 2. M. A. in Restoration of historical buildings & fabrics, Academic staff member, faculty of Art and Architecture, Shahid Bahonar University of Kerman, Iran, Received 2017/10/23 revised 2018/01/23 accepted 2018/02/13 available online 2018/06/22 Abstract The Zoroastrian’s tower of silence (Dakhma) in Kerman, is one of the most valuable religious monuments of Kerman and its history dates back to 1233-1261S.H. Alongside, there is the main and older Dakhma that probably belongs to Sassanians. Since about 1320 S.H. that Zoroastrians burial tradition was changed because of the social and hygienic reasons, it was disused and now, is in undesirable condition. On the base of contemporary theory of conservation, one of the best ways to conservation of architectural heritage is regeneration and rehabilitation and put them into consideration if possible. There is three basic method to conserve an architectural monument based on contemporary and classical theories: the first one is protective preservation with focus on maintenance of physical conditions of monument in present situation and prevents it from changes; the second is restoration in old usage for continuity, and the third one is revitalization and rehabilitation with new usage that is relevance to the authenticity and identity. -

A Daily Gatha Prayer

Weekly Zoroastrian Scripture Extract # 195 – A Daily Gatha Prayer of 16 verses based on Ahura Mazda's advice to Zarathushtra to drive away evil - Vendidad 11.1 - 2 Hello all Tele Class friends: A Daily Gatha Prayer – A Suggestion: In our WZSEs #192 – 194, we discussed the question by Zarathushtra answered by Ahura Mazda for the prayers to be recited to ward of evil from a dead body (Vendidad 11.1 – 2). There are 16 verses instructed by Ahura Mazda. We suggest that these verses from Gathas can also be used as a Daily Gatha Prayer for all to recite. In this WZSE #195, we present this prayer. I apologize for the length of this WZSE. Hope you enjoy reading and listening and following up as a prayer. And would like to hear your thoughts. Background: Our Vakhshur-e-Vakhshuraan Zarathushtra Spitamaan, in his Gathas, asks many questions to Ahura Mazda, but Ahura Mazda never replies him; instead Zarathushtra figures out the answers by using his Vohu Mana, the Good Mind! Later Avestan writers of Vendidad, Yashts, etc. thought this mode of questions and answers between Zarathushtra and Ahura Mazda, can be a powerful way to expound their own interpretations of our religion but in their questions by Zarathushtra, Ahura Mazda answers them right away! This gave their interpretations a powerful support! We see such questions and answers all over Vendidad, Yashts, etc.. Age of Vendidad has been debated in literature for a long time. It could be between 300 to 800 BC or earlier. According to Dinkard, our religion had 21 Nasks (volumes) on various subjects. -

605-616 Hinduism and Zoroastrianism.Indd

Hinduism and Zoroastrianism The term “Zoroastrianism,” coined in the 19th migrated to other parts of the world, and in the century in a colonial context, is inspired by a postcolonial age, especially since the 1960s, this Greek pseudo-etymological rendering (Zoro- movement has intensified, so that the so-called astres, where the second element is reminiscent diaspora is becoming the key factor for the future of the word for star) of the ancient Iranian name development of the religion (Stausberg, 2002b; Zaraϑuštra (etymology unclear apart from the sec- Hinnells, 2005). Given their tiny numbers, their ond element, uštra [camel]). This modern name non-proselytization and their constructive con- of the religion reflects the emphasis on Zarathus- tributions to Indian society (e.g. example through tra (Zoroaster) as its (presumed) founding figure their various charitable contributions [Hinnells, or prophet. 2000]), and their commitments to the army and Zoroastrianism and Hinduism share a remote other Indian institutions, which are routinely common original ancestry, but their historical celebrated in community publications, the Parsis trajectories over the millennia have been notably and their religion have so far not drawn forth any distinct. Just like Hinduism claims and maintains negative social response in India. a particular relationship to the spatial entity know Being offshoots of older Indo-European and as India, Zoroastrianism has conceived itself as Indo-Iranian poetic traditions, the oldest tex- the religion of the Iranians and -

Summer/June 2014

AMORDAD – SHEHREVER- MEHER 1383 AY (SHENSHAI) FEZANA JOURNAL FEZANA TABESTAN 1383 AY 3752 Z VOL. 28, No 2 SUMMER/JUNE 2014 ● SUMMER/JUNE 2014 Tir–Amordad–ShehreverJOUR 1383 AY (Fasli) • Behman–Spendarmad 1383 AY Fravardin 1384 (Shenshai) •N Spendarmad 1383 AY Fravardin–ArdibeheshtAL 1384 AY (Kadimi) Zoroastrians of Central Asia PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA Copyright ©2014 Federation of Zoroastrian Associations of North America • • With 'Best Compfiments from rrhe Incorporated fJTustees of the Zoroastrian Charity :Funds of :J{ongl(pnffi Canton & Macao • • PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA Vol 28 No 2 June / Summer 2014, Tabestan 1383 AY 3752 Z 92 Zoroastrianism and 90 The Death of Iranian Religions in Yazdegerd III at Merv Ancient Armenia 15 Was Central Asia the Ancient Home of 74 Letters from Sogdian the Aryan Nation & Zoroastrians at the Zoroastrian Religion ? Eastern Crosssroads 02 Editorials 42 Some Reflections on Furniture Of Sogdians And Zoroastrianism in Sogdiana Other Central Asians In 11 FEZANA AGM 2014 - Seattle and Bactria China 13 Zoroastrians of Central 49 Understanding Central 78 Kazakhstan Interfaith Asia Genesis of This Issue Asian Zoroastrianism Activities: Zoroastrian Through Sogdian Art Forms 22 Evidence from Archeology Participation and Art 55 Iranian Themes in the 80 Balkh: The Holy Land Afrasyab Paintings in the 31 Parthian Zoroastrians at Hall of Ambassadors 87 Is There A Zoroastrian Nisa Revival In Present Day 61 The Zoroastrain Bone Tajikistan? 34 "Zoroastrian Traces" In Boxes of Chorasmia and Two Ancient Sites In Sogdiana 98 Treasures of the Silk Road Bactria And Sogdiana: Takhti Sangin And Sarazm 66 Zoroastrian Funerary 102 Personal Profile Beliefs And Practices As Shown On The Tomb 104 Books and Arts Editor in Chief: Dolly Dastoor, editor(@)fezana.org AMORDAD SHEHREVER MEHER 1383 AY (SHENSHAI) FEZANA JOURNAL FEZANA Technical Assistant: Coomi Gazdar TABESTAN 1383 AY 3752 Z VOL. -

Iran: Zoroastrians

Country Policy and Information Note Iran: Zoroastrians Version 1.0 June 2017 Preface This note provides country of origin information (COI) and policy guidance to Home Office decision makers on handling particular types of protection and human rights claims. This includes whether claims are likely to justify the granting of asylum, humanitarian protection or discretionary leave and whether – in the event of a claim being refused – it is likely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under s94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002. Decision makers must consider claims on an individual basis, taking into account the case specific facts and all relevant evidence, including: the policy guidance contained with this note; the available COI; any applicable caselaw; and the Home Office casework guidance in relation to relevant policies. Country information COI in this note has been researched in accordance with principles set out in the Common EU [European Union] Guidelines for Processing Country of Origin Information (COI) and the European Asylum Support Office’s research guidelines, Country of Origin Information report methodology, namely taking into account its relevance, reliability, accuracy, objectivity, currency, transparency and traceability. All information is carefully selected from generally reliable, publicly accessible sources or is information that can be made publicly available. Full publication details of supporting documentation are provided in footnotes. Multiple sourcing is normally used to ensure that the information is accurate, balanced and corroborated, and that a comprehensive and up-to-date picture at the time of publication is provided. Information is compared and contrasted, whenever possible, to provide a range of views and opinions. -

Mecusi Geleneğinde Tektanrıcılık Ve Düalizm Ilişkisi

T.C. İSTANBUL ÜN İVERS İTES İ SOSYAL B İLİMLER ENST İTÜSÜ FELSEFE VE D İN B İLİMLER İ ANAB İLİM DALI DİNLER TAR İHİ B İLİM DALI DOKTORA TEZ İ MECUS İ GELENE Ğİ NDE TEKTANRICILIK VE DÜAL İZM İLİŞ KİSİ Mehmet ALICI (2502050181) Tez Danı şmanı: Prof.Dr. Şinasi GÜNDÜZ İstanbul 2011 T.C. İSTANBUL ÜN İVERS İTES İ SOSYAL B İLİMLER ENST İTÜSÜ FELSEFE VE D İN B İLİMLER İ ANAB İLİM DALI DİNLER TAR İHİ B İLİM DALI DOKTORA TEZ İ MECUS İ GELENE Ğİ NDE TEKTANRICILIK VE DÜAL İZM İLİŞ KİSİ Mehmet ALICI (2502050181) Tez Danı şmanı: Prof.Dr. Şinasi GÜNDÜZ (Bu tez İstanbul Üniversitesi Bilimsel Ara ştırma Projeleri Komisyonu tarafından desteklenmi ştir. Proje numarası:4247) İstanbul 2011 ÖZ Bu çalı şma Mecusi gelene ğinde tektanrıcılık ve düalizm ili şkisini ortaya çıkı şından günümüze kadarki tarihsel süreç içerisinde incelemeyi hedef edinir. Bu ba ğlamda Mecusilik üç temel teolojik süreç çerçevesinde ele alınmaktadır. Bu ba ğlamda birinci teolojik süreçte Mecusili ğin kurucusu addedilen Zerdü şt’ün kendisine atfedilen Gatha metninde tanrı Ahura Mazda çerçevesinde ortaya koydu ğu tanrı tasavvuru incelenmektedir. Burada Zerdü şt’ün anahtar kavram olarak belirledi ği tanrı Ahura Mazda ve onunla ili şkilendirilen di ğer ilahi figürlerin ili şkisi esas alınmaktadır. Zerdü şt sonrası Mecusi teolojisinin şekillendi ği Avesta metinleri ikinci teolojik süreci ihtiva etmektedir. Bu dönem Zerdü şt’ten önceki İran’ın tanrı tasavvurlarının yeniden kutsal metne yani Avesta’ya dahil edilme sürecini yansıtmaktadır. Dolayısıyla Avesta edebiyatı Zerdü şt sonrası dönü şen bir teolojiyi sunmaktadır. Bu noktada ba şta Ahura Mazda kavramı olmak üzere, Zerdü şt’ün Gatha’da ortaya koydu ğu mefhumların de ğişti ği görülmektedir. -

Position Specifications

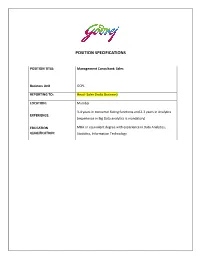

POSITION SPECIFICATIONS POSITION TITLE: Management Consultant: Sales Business Unit GCPL REPORTING TO: Head- Sales (India Business) LOCATION: Mumbai 3-4 years in consumer facing functions and 2-3 years in Analytics EXPERIENCE: (experience in Big Data analytics is mandatory) EDUCATION MBA or equivalent degree with experience in Data Analytics, QUALIFICATION: Statistics, Information Technology Overview of the organization Established in 1897, the Godrej Group has its roots in India's Swadeshi movement. Our founder, Ardeshir Godrej, lawyer-turned-serial entrepreneur failed with a few businesses, before he struck gold with the locks business that you know today. One of India's most trusted brands, with revenues of USD 4.1 billion, Godrej enjoys the patronage of over 600 million Indians across our consumer goods, real estate, appliances, agri and many other businesses. You think of Godrej as such an integral part of India that you may be surprised to know that over 25 per cent of our business is done overseas. We promise Godrejites a culture of tough love; take serious bets on them and differentiate basis performance. We also understand that our team members play multi-faceted roles and so, we strongly encourage them to explore their whole selves. Our canvas is growing. In fact, our Vision for 2020 is to be 10 times the size we were in 2010. We truly believe that while our amazing past distinguishes us, we are only as good as what we do next. Godrej Consumer Products Limited is the largest home-grown home and personal care company in India. We are constantly innovating to delight our consumers with more exciting, superior quality products at affordable prices. -

Godrej Group Case Study

Evolution of a Family Business - Godrej Group Case Study Submitted by (Section C- Group 4): Abhishek Kumar(PGP11/129) Balaji Manohar(PGP11/140) Karthik Kumar(PGP11/151) Prashant Gangwal (PGP11/162) Santosh(PGP11/173) Supriya(PGP11/184) Group Assignment – – Organizational Behavior II – – IIMK Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................................................... 5 Overview of the Godrej Group ................................................................................................................................... 7 Organizational Structure .............................................................................................................................................. 77 Godrej Group Companies ........................................................................................................................................ 8 Competition .................................................................................................................................................................... 9 Family Business Model .......................................................................................................................................... 10 Key Success factors –– Family Business Model ..........................................................................................