605-616 Hinduism and Zoroastrianism.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iranshah Udvada Utsav

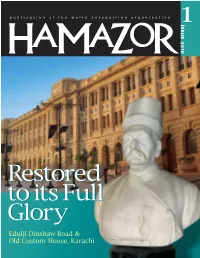

HAMAZOR - ISSUE 1 2016 Dr Nergis Mavalvala Physicist Extraordinaire, p 43 C o n t e n t s 04 WZO Calendar of Events 05 Iranshah Udvada Utsav - vahishta bharucha 09 A Statement from Udvada Samast Anjuman 12 Rules governing use of the Prayer Hall - dinshaw tamboly 13 Various methods of Disposing the Dead 20 December 25 & the Birth of Mitra, Part 2 - k e eduljee 22 December 25 & the Birth of Jesus, Part 3 23 Its been a Blast! - sanaya master 26 A Perspective of the 6th WZYC - zarrah birdie 27 Return to Roots Programme - anushae parrakh 28 Princeton’s Great Persian Book of Kings - mahrukh cama 32 Firdowsi’s Sikandar - naheed malbari 34 Becoming my Mother’s Priest, an online documentary - sujata berry COVER 35 Mr Edulji Dinshaw, CIE - cyrus cowasjee Image of the Imperial 39 Eduljee Dinshaw Road Project Trust - mohammed rajpar Custom House & bust of Mr Edulji Dinshaw, CIE. & jameel yusuf which stands at Lady 43 Dr Nergis Mavalvala Dufferin Hospital. 44 Dr Marlene Kanga, AM - interview, kersi meher-homji PHOTOGRAPHS 48 Chatting with Ami Shroff - beyniaz edulji 50 Capturing Histories - review, freny manecksha Courtesy of individuals whose articles appear in 52 An Uncensored Life - review, zehra bharucha the magazine or as 55 A Whirlwind Book Tour - farida master mentioned 57 Dolly Dastoor & Dinshaw Tamboly - recipients of recognition WZO WEBSITE 58 Delhi Parsis at the turn of the 19C - shernaz italia 62 The Everlasting Flame International Programme www.w-z-o.org 1 Sponsored by World Zoroastrian Trust Funds M e m b e r s o f t h e M a n a g i -

Copyright by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani 2012

Copyright by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani 2012 The Dissertation Committee for Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Princes, Diwans and Merchants: Education and Reform in Colonial India Committee: _____________________ Gail Minault, Supervisor _____________________ Cynthia Talbot _____________________ William Roger Louis _____________________ Janet Davis _____________________ Douglas Haynes Princes, Diwans and Merchants: Education and Reform in Colonial India by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2012 For my parents Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without help from mentors, friends and family. I want to start by thanking my advisor Gail Minault for providing feedback and encouragement through the research and writing process. Cynthia Talbot’s comments have helped me in presenting my research to a wider audience and polishing my work. Gail Minault, Cynthia Talbot and William Roger Louis have been instrumental in my development as a historian since the earliest days of graduate school. I want to thank Janet Davis and Douglas Haynes for agreeing to serve on my committee. I am especially grateful to Doug Haynes as he has provided valuable feedback and guided my project despite having no affiliation with the University of Texas. I want to thank the History Department at UT-Austin for a graduate fellowship that facilitated by research trips to the United Kingdom and India. The Dora Bonham research and travel grant helped me carry out my pre-dissertation research. -

Consciousness” in Zarathushtra’S Teachings

THE PHILOSOPHICAL CONCEPT OF “CONSCIOUSNESS” IN ZARATHUSHTRA’S TEACHINGS Zarathushtra, a visionary giant, must be credited as the father of modern philosophical thought and opinions. Through his poetic hymns he transmits the prophetic notions of his Divine Revelation, leaving behind words of profound psycho-social significance, which have triggered off an endless chain of philosophical discussions on the matters of the mind and human conscious senses. The modern meaning of the word “Consciousness” is perceived differently in different disciplines. For the philosophical purpose of this paper let us make the meaning simple. The most fundamental aspect of “Consciousness” is the ability to sense existence/being. It is a notion that is recognised with the world around us and in our personal experience. It, naturally, follows on the appraisal that accompanies the experience of existence. The core sense of being “Conscious” involves a subjective condition of Access Consciousness, which occurs when we are able to access /to perceive through our senses the world around us in a generalised state of alertness or arousal. We are, therefore, able to respond /to imagine i.e. when we are not in deep sleep, in coma or under anaesthesia. Another form, a Phenomenal Consciousness occurs when we are aware that we have a subjective experience or feeling of phenomena /happenings /events around us. A third sense of (Objective) Consciousness is the awareness of a particular object or event of a conscious state. Zarathushtra’s words impart a clear insight into the reality of being. His concept of Reality is a physical world (‘out there’) of perceptual consciousness, which truly exists as our personal presence on earth. -

Chirantana Info

Jagannath Organization for Global Awareness (JOGA) Newsletter Issue No: 21 August 28, 2008 http://www.jogaworld.org 1 Bhagabat Gita: The Sacred Hindu Scripture Contents Bhajan Program on August 16th, 2008: Jhulan Jatra, Raksha Bandhan and Balabhadra Janma - pg 2 Janmastami Special: Krishna Mangalacharan & Bandana by Kabi Banamali - pg 3 Jaya Sankha Gadadhara …Dehi Padam - pg 4 Prayer and the Purpose - pg 5 Srasta He Tume (Bhajan by Bigyani Das) - pg 9 Siddhartha by Herman Hesse - pg 9 Building the Chariot (Naresh Das) - pg 10 Rathajatra Sponsors – pg 11 September is Children’s Month - pg 13 Bhagabat Gita Devotees on Move – pg 13 Bhajan Schedule: Third (3rd) Saturday of every month @kcÐcúÐ NÊXÐÒLh jaàbË[Ðh¯yÞ[Ó Ð Place: Hindu Temple, 10001 Riggs Road, @kcÐ]Þ¾ c^ÔÕ Q bË[Ð_Ðc« Ha Q ÐÐ Adelphi, MD 20783 (Tel: 301-445-2165) Time: 6:00 –9:00 PM Bhajan, Philosophiccal aham Atma gudAkesha sarva-bhutAsaya-sthitah Discussion, Arati, and Prasad aham Adis cha madhyam cha bhutAnAm anta eva cha HkÞ ÒhìÐLVÞ bNa]ç NÑ[Ðe ]hc @^ÔЯÒe aÀà_Ð LeÐdÐBRÞ Ð hÍÑ bNaÐ_ LkÞÒm - cÊÜ jcª SÑae kó]¯Òe \úaÐ AcúÐ @ÒV, cÊÜ jcª `ÍÐZÑe A]Þ (cËf), c^Ô HaÕ @« @ÒV Ð Chirantana Info: Lord Krishna said to Arjuna in verse 20th of Chirantana is the bi-annual newsletter Chapter 10 (Yoga of Infinite Glories of the Ultimate of Jagannath Organization for Global Truth – Bibhuti-BistAra Yoga) - “I am the Awareness (JOGA). Chirantan is Supersoul, O Arjuna, seated in the hearts of all published in February and August living entities. -

Fezanabulletin

Newsletter of the Federation of Zoroastrian Associations of North America FEZANA bulletin December 2015 / VOLUME 5 • ISSUE 12 First Ever Iranshah Udvada Utsav The first Iranshah Udvada Utsav (IUU) celebration takes place over a three-day period from December 25-27, 2015 in Udvada, Gujarat, India. Inspired and supported by Hon’ble Shri Narendra Modi, Prime Minister of India, who speaks highly of the Zarathushti community’s unparalleled contribution towards India’s nation building, UPCOMING DATES the IUU will host thousands of Zarathushtis this December who will travel to Udvada from throughout India and from abroad to Through Jan 24, 2016 partake in the festivities. Prime Minister Modi Parsi Silk and Muslin from Iran, India and China Exhibition; East recognizes that Udvada (home of the West Center, Honolulu, HI. East Iranshah Atash Behram, the most sacred West Center Arts Program Atash Behram in India) showcases the history of the Parsi community and it was his Through September 2016 Persepolis: Images of an Empire. keen desire to project Udvada as a place of Oriental Institute – Univ of Chicago. harmony, religious tolerance and opportunities. Thus, after much hard work by its core project team, the first ever festival at Udvada has been organized, with the hope December 25-27, 2015 that it becomes an annual tradition. Iranshah Udvada Utsav (IUU); Udvada, India The program includes Parsi naataks, entertainment acts by children, youth and http://www.iuu.org.in/ adults of our community, Udvada heritage walks, treasure hunt, religious talks and Dec 28, 2015-Jan 2, 2016 other youth programs. Workshops and presentations are also planned which will 6th World Zoroastrian Youth showcase Parsi culture and traditions. -

What an Auspicious Day Today Is! It Is Pak Iranshah Atash Behram Padshah Saheb's Salgreh – Adar Mahino and Adar Roj! Adar Ma

Weekly Zoroastrian Scripture Extract # 102 – Pak Iranshah Atash Behram Padshah Salgreh - Adar Mahino and Adar Roj Parab - We approach Thee Ahura Mazda through Thy Holy Fire - Yasna Haptanghaaiti - Moti Haptan Yasht - Yasna 36 Verses 1 - 3 Hello all Tele Class friends: What an auspicious day today is! It is Pak Iranshah Atash Behram Padshah Saheb’s Salgreh – Adar Mahino and Adar Roj! Adar Mahina nu Parab! Today in our Udvada Gaam, hundreds of Humdins from all over India will congregate to pay their homage to Padshah Saheb and then all of them will be treated by a sumptuous Gahambar Lunch thanks to the Petit Family, an annual event! Over 1500 Humdins will partake this Gahambar lunch! I have attached 3 photos of the Salgreh in 2004 showing the long queue, Gahambar lunch Pangat and the Master Chefs! In our religion, Fire is regarded as one of the most amazing creations of Dadar Ahura Mazda! In fact, in Atash Nyayesh, Fire is referred to as the Son of Ahura Mazda! In our Agiyaris, Adarans and Atash Behrams, the focal point of our worship is the consecrated Fire and hence many people call us Fire Worshippers in their ignorance. That brings to mind the famous quote of the great Persian poet, Ferdowsi, the Shahnameh Author: “Ma gui keh Atash parastand budan, Parastandeh Pak Yazdaan budan!” “Do not say that they are Fire Worshippers! They are worshippers of Pak Yazdaan (Dadar Ahura Mazda) (through Holy Fire!)” In our previous weeklies, we have presented verses from Atash Nyayesh in praise of our consecrated Fires! The above point by Ferdowsi is well supported by the second Karda (chapter) of Yasna Haptanghaaiti, Yasna 36, the seven Has (chapters) attributed by some to Zarathushtra himself after his Gathas and many attribute them to the immediate disciples of Zarathushtra. -

On the Good Faith

On the Good Faith Zoroastrianism is ascribed to the teachings of the legendary prophet Zarathustra and originated in ancient times. It was developed within the area populated by the Iranian peoples, and following the Arab conquest, it formed into a diaspora. In modern Russia it has evolved since the end of the Soviet era. It has become an attractive object of cultural produc- tion due to its association with Oriental philosophies and religions and its rearticulation since the modern era in Europe. The lasting appeal of Zoroastrianism evidenced by centuries of book pub- lishing in Russia was enlivened in the 1990s. A new, religious, and even occult dimension was introduced with the appearance of neo-Zoroastrian groups with their own publications and online websites (dedicated to Zoroastrianism). This study focuses on the intersectional relationships and topical analysis of different Zoroastrian themes in modern Russia. On the Good Faith A Fourfold Discursive Construction of Zoroastrianism in Contemporary Russia Anna Tessmann Anna Tessmann Södertörns högskola SE-141 89 Huddinge [email protected] www.sh.se/publications On the Good Faith A Fourfold Discursive Construction of Zoroastrianism in Contemporary Russia Anna Tessmann Södertörns högskola 2012 Södertörns högskola SE-141 89 Huddinge www.sh.se/publications Cover Image: Anna Tessmann Cover Design: Jonathan Robson Layout: Jonathan Robson & Per Lindblom Printed by E-print, Stockholm 2012 Södertörn Doctoral Dissertations 68 ISSN 1652-7399 ISBN 978-91-86069-50-6 Avhandlingar utgivna vid -

Decline in the Popularity of Sun Worship Chapter- Vi

CJI--IAPTER - V[ DECLINE IN THE POPULARITY OF SUN WORSHIP CHAPTER- VI DECLINE IN THE POPULARITY OF SUN WORSHIP The popularity of the Sun worship in Bengal down to the end of Hindu rule is indicated by the opening verse in the copperplates of Visvarupasena and Suryasena in praise of the Sun god. The extant remains of the icons of Surya, dated or undated, also suggest the continuity of Sun worship until at least the early mediaeval period. Perhaps. this popularity was partly the cause as well as effect of the deep-rooted belief recorded on the pedestal of a Surya image from BairhaHa (Dinajpur District) that the god was the healer of all diseases ('samasta-roganiim harllii l However, since the early part of the 13'h century A.D. things began to change in the disfavour of the Sun-cult. In actuality. the process started long back, specifically since the Sena Period. The northern style SGrya and his worship probably did not last long alter the Varman-Sena period: at least we hardly come across any such images aflerwards. There could be various reasons t(1r the subsequent decline in the importance and anthropomorphic worship of the Sun in early Bengal. However. it is also to be kept in mind that the solar worship in the t(ml1S stated alxl\e did not only disappear from this part of eastern India, but also from the rest of the Indian sub-continent. Naturally. the question rises as to what led to the decline of the solar-cult. No mysticism, symbolism or high philosophy around SOrya: The daily visibility of the Sun to naked eye prevented the sectarians to develop any mysticism, symbolism or high philosophy centering round him. -

Section 124- Unpaid and Unclaimed Dividend

Sr No First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio Amount 1 ASHOK KUMAR GOLCHHA 305 ASHOKA CHAMBERS ADARSHNAGAR HYDERABAD 500063 0000000000B9A0011390 36.00 2 ADAMALI ABDULLABHOY 20, SUKEAS LANE, 3RD FLOOR, KOLKATA 700001 0000000000B9A0050954 150.00 3 AMAR MANOHAR MOTIWALA DR MOTIWALA'S CLINIC, SUNDARAM BUILDING VIKRAM SARABHAI MARG, OPP POLYTECHNIC AHMEDABAD 380015 0000000000B9A0102113 12.00 4 AMRATLAL BHAGWANDAS GANDHI 14 GULABPARK NEAR BASANT CINEMA CHEMBUR 400074 0000000000B9A0102806 30.00 5 ARVIND KUMAR DESAI H NO 2-1-563/2 NALLAKUNTA HYDERABAD 500044 0000000000B9A0106500 30.00 6 BIBISHAB S PATHAN 1005 DENA TOWER OPP ADUJAN PATIYA SURAT 395009 0000000000B9B0007570 144.00 7 BEENA DAVE 703 KRISHNA APT NEXT TO POISAR DEPOT OPP OUR LADY REMEDY SCHOOL S V ROAD, KANDIVILI (W) MUMBAI 400067 0000000000B9B0009430 30.00 8 BABULAL S LADHANI 9 ABDUL REHMAN STREET 3RD FLOOR ROOM NO 62 YUSUF BUILDING MUMBAI 400003 0000000000B9B0100587 30.00 9 BHAGWANDAS Z BAPHNA MAIN ROAD DAHANU DIST THANA W RLY MAHARASHTRA 401601 0000000000B9B0102431 48.00 10 BHARAT MOHANLAL VADALIA MAHADEVIA ROAD MANAVADAR GUJARAT 362630 0000000000B9B0103101 60.00 11 BHARATBHAI R PATEL 45 KRISHNA PARK SOC JASODA NAGAR RD NR GAUR NO KUVO PO GIDC VATVA AHMEDABAD 382445 0000000000B9B0103233 48.00 12 BHARATI PRAKASH HINDUJA 505 A NEEL KANTH 98 MARINE DRIVE P O BOX NO 2397 MUMBAI 400002 0000000000B9B0103411 60.00 13 BHASKAR SUBRAMANY FLAT NO 7 3RD FLOOR 41 SEA LAND CO OP HSG SOCIETY OPP HOTEL PRESIDENT CUFFE PARADE MUMBAI 400005 0000000000B9B0103985 96.00 14 BHASKER CHAMPAKLAL -

Late Onset of Sufism in Azerbaijan and the Influence of Zarathustra Thoughts on Its Fundamentals

International Journal of Philosophy and Theology September 2014, Vol. 2, No. 3, pp. 93-106 ISSN: 2333-5750 (Print), 2333-5769 (Online) Copyright © The Author(s). 2014. All Rights Reserved. Published by American Research Institute for Policy Development DOI: 10.15640/ijpt.v2n3a7 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.15640/ijpt.v2n3a7 Late Onset of Sufism in Azerbaijan and the Influence of Zarathustra Thoughts on its Fundamentals Parisa Ghorbannejad1 Abstract Islamic Sufism started in Azerbaijan later than other Islamic regions for some reasons.Early Sufis in this region had been inspired by mysterious beliefs of Zarathustra which played an important role in future path of Sufism in Iran the consequences of which can be seen in illumination theory. This research deals with the reason of the delay in the advent of Sufism in Azerbaijan compared with other regions in a descriptive analytic method. Studies show that the deficiency of conqueror Arabs, loyalty of ethnic people to Iranian religion and the influence of theosophical beliefs such as heart's eye, meeting the right, relation between body and soul and cross evidences in heart had important effects on ideas and thoughts of Azerbaijan's first Sufis such as Ebn-e-Yazdanyar. Investigating Arab victories and conducting case studies on early Sufis' thoughts and ideas, the author attains considerable results via this research. Keywords: Sufism, Azerbaijan, Zarathustra, Ebn-e-Yazdanyar, Islam Introduction Azerbaijan territory2 with its unique geography and history, was the cultural center of Iran for many years in Sasanian era and was very important for Zarathustra religion and Magi class. 1 PhD, Faculty of Science, Islamic Azad University, Urmia Branch,WestAzarbayjan, Iran. -

17 Zoroastrianism

17 Zoroastrianism This statement was prepared by the Athravan Education Trust and Zoroastrian Studies, the two main academic bodies responsible to the Zoroastrian faith for theological developments and study. Whoever teaches care for all these seven creations, does well and pleases the Bounteous Immortals; then his soul will never arrive at kinship with the Hostile Spirit. When he has cared for the creations, the care of these Bounteous Immortals is for him, and he must teach this to all mankind in the material world. —Shayasht ne Shayast (15:6)1 These actions, according to Zoroastrianism, will lead toward “making the world wonderful,” when the world will be restored to a perfect state. In this state the material world will never grow old, never die, never decay, will be ever living and ever increasing and master of its wish. The dead will rise, life and immortality will come, and the world will be restored to a perfect state in accordance with the Will of Ahura Mazda (Lord of Wisdom). The role of humanity in the world is to serve and honor not just the Wise Lord but the Seven Bounteous Creations of the sky, water, earth, plants, animals, man, and fire—gifts of God on High to humanity on earth. The great strength of the Zoroastrian faith is that it enjoins the caring of the physical world not merely to seek spiritual salvation, but because 1. The Shayasht ne Shayast is a compilation of miscellaneous laws dealing with proper and improper behavior. 145 146 FAITH IN CONSERVATION human beings, as the purposeful creation of God, are seen as the natural motivators or overseers of the Seven Creations. -

South-Indian Images of Gods and Goddesses

ASIA II MB- • ! 00/ CORNELL UNIVERSITY* LIBRARY Date Due >Sf{JviVre > -&h—2 RftPP )9 -Af v^r- tjy J A j£ **'lr *7 i !! in ^_ fc-£r Pg&diJBii'* Cornell University Library NB 1001.K92 South-indian images of gods and goddesse 3 1924 022 943 447 AGENTS FOR THE SALE OF MADRAS GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS. IN INDIA. A. G. Barraud & Co. (Late A. J. Combridge & Co.)> Madras. R. Cambrav & Co., Calcutta. E. M. Gopalakrishna Kone, Pudumantapam, Madura. Higginbothams (Ltd.), Mount Road, Madras. V. Kalyanarama Iyer & Co., Esplanade, Madras. G. C. Loganatham Brothers, Madras. S. Murthv & Co., Madras. G. A. Natesan & Co., Madras. The Superintendent, Nazair Kanun Hind Press, Allahabad. P. R. Rama Iyer & Co., Madras. D. B. Taraporevala Sons & Co., Bombay. Thacker & Co. (Ltd.), Bombay. Thacker, Spink & Co., Calcutta. S. Vas & Co., Madras. S.P.C.K. Press, Madras. IN THE UNITED KINGDOM. B. H. Blackwell, 50 and 51, Broad Street, Oxford. Constable & Co., 10, Orange Street, Leicester Square, London, W.C. Deighton, Bell & Co. (Ltd.), Cambridge. \ T. Fisher Unwin (Ltd.), j, Adelphi Terrace, London, W.C. Grindlay & Co., 54, Parliament Street, London, S.W. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. (Ltd.), 68—74, iCarter Lane, London, E.C. and 25, Museum Street, London, W.C. Henry S. King & Co., 65, Cornhill, London, E.C. X P. S. King & Son, 2 and 4, Great Smith Street, Westminster, London, S.W.- Luzac & Co., 46, Great Russell Street, London, W.C. B. Quaritch, 11, Grafton Street, New Bond Street, London, W. W. Thacker & Co.^f*Cre<d Lane, London, E.O? *' Oliver and Boyd, Tweeddale Court, Edinburgh.