Encyclopedia Interrupta, Or Gale's Unfinished

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Medieval Jewish Philosophy and Its Literary Forms'

H-Judaic Lawee on Hughes and Robinson, 'Medieval Jewish Philosophy and Its Literary Forms' Review published on Monday, March 16, 2020 Aaron W. Hughes, James T. Robinson, eds. Medieval Jewish Philosophy and Its Literary Forms. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2019. viii + 363 pp. $100.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-253-04252-1. Reviewed by Eric Lawee (Bar-Ilan University)Published on H-Judaic (March, 2020) Commissioned by Barbara Krawcowicz (Norwegian University of Science and Technology) Printable Version: http://www.h-net.org/reviews/showpdf.php?id=54753 Among the religious and intellectual innovations in which medieval Judaism abounds, none sparked controversy more than the attempt of certain rabbis and scholars to promote teachings of ancient Greek philosophy. Most notable, of course, was Moses Maimonides, the foremost legist and theologian of the age. Not only did he cultivate Greco-Arabic philosophy and science, but he also taught the radical proposition that knowledge of some of its branches was essential for a true understanding of revealed scripture and for worship of God in its purest form. As an object of modern scholarship, medieval philosophy has not suffered from a lack of attention. Since the advent of Wissenschaft des Judentums more than a century and half ago, studies have proliferated, whether on specific topics (e.g., theories of creation), leading figures (e.g., Saadiah Gaon, Judah Halevi, Maimonides), or the historical, religious, and intellectual settings in which Jewish engagements with philosophy occurred—first in -

The Attitude Towards Democracy in Medieval Jewishphilosophy*

THE ATTITUDE TOWARDS DEMOCRACY IN MEDIEVAL JEWISHPHILOSOPHY* Avraham Melamed Medieval Jewish thought, following Platonic and Muslim political was philosophy, on the one hand, and halakhic concepts, on the other, basically, although reluctantly, monarchist, and inherently anti democratic. It rejected outright what we term here as the ancient Greek variety of liberal democracy, which went against its basic philosophical and theological assumptions. I the In his various writings Professor DJ. Elazar characterized Jewish polity as a "republic with strong democratic overtones," an which nevertheless was in reality generally "aristocratic repub ? lic in the classic sense of the term rule by a limited number who as take upon themselves an obligation or conceive of themselves a to It is true having special obligation to their people and God." a in that the Jewish polity is "rooted in democratic foundation," that it is based upon the equality of all (adultmale) Jewsand their basic rightand obligation to participate in the establishmentand is as far as the maintenance of the body politic.1 But this was a true "democratic overtones" of this republic went. It republic no some of what is enough, but democracy. It did have components was a termed "communal democracy," but not liberal democracy. over the centuries were The various Jewish polities which existed JewishPolitical Studies Review 5:1-2 (Spring 1993) 33 This content downloaded by the authorized user from 192.168.82.205 on Tue, 27 Nov 2012 07:16:21 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 34 Avrahatn Melamed generally very aristocratic in terms of their actual regimes. -

אוסף מרמורשטיין the Marmorstein Collection

אוסף מרמורשטיין The Marmorstein Collection Brad Sabin Hill THE JOHN RYLANDS LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF MANCHESTER Manchester 2017 1 The Marmorstein Collection CONTENTS Acknowledgements Note on Bibliographic Citations I. Preface: Hebraica and Judaica in the Rylands -Hebrew and Samaritan Manuscripts: Crawford, Gaster -Printed Books: Spencer Incunabula; Abramsky Haskalah Collection; Teltscher Collection; Miscellaneous Collections; Marmorstein Collection II. Dr Arthur Marmorstein and His Library -Life and Writings of a Scholar and Bibliographer -A Rabbinic Literary Family: Antecedents and Relations -Marmorstein’s Library III. Hebraica -Literary Periods and Subjects -History of Hebrew Printing -Hebrew Printed Books in the Marmorstein Collection --16th century --17th century --18th century --19th century --20th century -Art of the Hebrew Book -Jewish Languages (Aramaic, Judeo-Arabic, Yiddish, Others) IV. Non-Hebraica -Greek and Latin -German -Anglo-Judaica -Hungarian -French and Italian -Other Languages 2 V. Genres and Subjects Hebraica and Judaica -Bible, Commentaries, Homiletics -Mishnah, Talmud, Midrash, Rabbinic Literature -Responsa -Law Codes and Custumals -Philosophy and Ethics -Kabbalah and Mysticism -Liturgy and Liturgical Poetry -Sephardic, Oriental, Non-Ashkenazic Literature -Sects, Branches, Movements -Sex, Marital Laws, Women -History and Geography -Belles-Lettres -Sciences, Mathematics, Medicine -Philology and Lexicography -Christian Hebraism -Jewish-Christian and Jewish-Muslim Relations -Jewish and non-Jewish Intercultural Influences -

ENCYCLOPAEDIA JUDAICA, Second Edition, Volume 11 Worship

jerusalem worship. Jerome also made various translations of the Books pecially in letter no. 108, a eulogy on the death of his friend of Judith and Tobit from an Aramaic version that has since Paula. In it, Jerome describes her travels in Palestine and takes disappeared and of the additions in the Greek translation of advantage of the opportunity to mention many biblical sites, Daniel. He did not regard as canonical works the Books of Ben describing their condition at the time. The letter that he wrote Sira and Baruch, the Epistle of Jeremy, the first two Books of after the death of Eustochium, the daughter of Paula, serves as the Maccabees, the third and fourth Books of Ezra, and the a supplement to this description. In his comprehensive com- additions to the Book of Esther in the Septuagint. The Latin mentaries on the books of the Bible, Jerome cites many Jewish translations of these works in present-day editions of the Vul- traditions concerning the location of sites mentioned in the gate are not from his pen. Bible. Some of his views are erroneous, however (such as his in Dan. 11:45, which ,( ּ ַ אַפדְ נ וֹ ) The translation of the Bible met with complaints from explanation of the word appadno conservative circles of the Catholic Church. His opponents he thought was a place-name). labeled him a falsifier and a profaner of God, claiming that Jerome was regularly in contact with Jews, but his atti- through his translations he had abrogated the sacred traditions tude toward them and the law of Israel was the one that was of the Church and followed the Jews: among other things, they prevalent among the members of the Church in his genera- invoked the story that the Septuagint had been translated in a tion. -

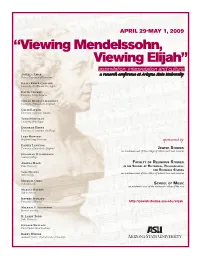

“Viewing Mendelssohn, Viewing Elijah”

APRIL 29-MAY 1, 2009 “Viewing Mendelssohn, Viewing Elijah” assimilation, interpretation and culture Ariella Amar a rreses eearcharch cconferenceonference atat ArizonaArizona StateState UniversityUniversity Hebrew University of Jerusalem Julius Reder Carlson University of California, Los Angeles David Conway University College London Sinéad Dempsey-Garratt University of Manchester, England Colin Eatock University of Toronto, Canada Todd Endelman University of Michigan Deborah Hertz University of California, San Diego Luke Howard Brigham Young University sponsored by Daniel Langton University of Manchester, England JEWISH STUDIES an academic unit of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences Jonathan D. Lawrence Canisius College Angela Mace FACULTY OF RELIGIOUS STUDIES Duke University IN THE SCHOOL OF HISTORICAL, PHILOSOPHICAL AND RELIGIOUS STUDIES Sara Malena Wells College an academic unit of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences Michael Ochs Ochs Editorial SCHOOL OF MUSIC an academic unit of the Herberger College of the Arts Marcus Rathey Yale University Jeffrey Sposato University of Houston http://jewishstudies.asu.edu/elijah Michael P. Steinberg Brown University R. Larry Todd Duke University Donald Wallace United States Naval Academy Barry Wiener Graduate Center, City University of New York Viewing Mendelssohn, Viewing Elijah: assimilation, interpretation and culture a research conference at Arizona State University / April 29 – May 1, 2009 Conference Synopsis From child prodigy to the most celebrated composer of his time: Felix Mendelssohn -

Pentateuch Country: Italy Value: AUCTION Genre: Religion Year Published: 1475 Author: Rashi Why Important: the Pentateuch Are T

Pentateuch Country: Italy Value: AUCTION Genre: Religion Year Published: 1475 Author: Rashi Why Important: The Pentateuch are the first five books of the Bible, sacred to both Jews and Christians. Moses is credited with writing Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy. Arba’ Turim Country: Italy Value: AUCTION Genre: Religion Year Published: 1475 Author: Rabbi Jacob ben Asher Why Important: The first book of Jewish religious law, originally composed in manuscript in the late 13th or early 14th century. Job Country: Italy Value: AUCTION Genre: Religion Year Published: 1477 Author: Levi ben Gershon Why Important: Levin ben Gershon lived in the late 13th and early 14th century as a scientist, philosopher, and doctor in France. He is famous as a commentator; this book is a commentary on Job. Nofet Zufim Country: Italy Value: AUCTION Also Known As: The Honeycomb’s Flow Genre: Language Year Published: 1475-1480 Author: Judah ben Jehiel Refe (Judah Messer Leon) Why Important: Jewish Italian scholar’s book on Renaissance rhetoric; also the first Hebrew book of a living author to be printed. Il Commodo comedia di Antonio Landi Country: Italy Value: AUCTION Also Known As: The Server?: Comedy of Antonio Landi Genre: History Year Published: 1539 Author: Pier Francesco Giambullari Why Important: Account of the wedding in Florence of Cosimo l de’ Medici and Eleanora of Toledo. Breve descrizione delle pomp funereale fatta nelle essquie del serenmissio D. Francesco Medici II Country: Italy Value: AUCTION Also Known As: Brief Description of the funeral of D. Francesco Medici II Genre: History Year Published: 1587 Author: Giovanni Vittorio Soderini Why Important: Account of the Funeral in Florence of Francesco l de’ Medici. -

Sixteenth-Century Hebrew Books in the Library of Congress

Sixteenth-Century Hebrew Books at the Library of Congress A Finding Aid פה Washington D.C. June 18, 2012 ` Title-page from Maimonides’ Moreh Nevukhim (Sabbioneta: Cornelius Adelkind, 1553). From the collections of the Hebraic Section, Library of Congress, Washington D.C. i Table of Contents: Introduction to the Finding Aid: An Overview of the Collection . iii The Collection as a Testament to History . .v The Finding Aid to the Collection . .viii Table: Titles printed by Daniel Bomberg in the Library of Congress: A Concordance with Avraham M. Habermann’s List . ix The Finding Aid General Titles . .1 Sixteenth-Century Bibles . 42 Sixteenth-Century Talmudim . 47 ii Sixteenth-Century Hebrew Books in the Library of Congress: Introduction to the Finding Aid An Overview of the Collection The art of Hebrew printing began in the fifteenth century, but it was the sixteenth century that saw its true flowering. As pioneers, the first Hebrew printers laid the groundwork for all the achievements to come, setting standards of typography and textual authenticity that still inspire admiration and awe.1 But it was in the sixteenth century that the Hebrew book truly came of age, spreading to new centers of culture, developing features that are the hallmark of printed books to this day, and witnessing the growth of a viable book trade. And it was in the sixteenth century that many classics of the Jewish tradition were either printed for the first time or received the form by which they are known today.2 The Library of Congress holds 675 volumes printed either partly or entirely in Hebrew during the sixteenth century. -

Mishkan Issue 59, 2009 – Jesus – Yeshua…

Issue 59 / 2009 MISHKAN A Forum on the Gospel and the Jewish People ISSUE 59 / 2009 General Editor: Kai Kjær-Hansen Pasche Institute of Jewish Studies · A Ministry of Criswell College All Rights Reserved. For permissions please contact [email protected] For subscriptions and back issues visit www.mishkanstore.org TABLE OF CONTENTS Editorial 3 Kai Kjaer-Hansen Resolution on Christian Zionism and Jewish Evangelism 4 Kai Kjaer-Hansen A Survey of Israeli Knowledge and Attitudes toward Jesus 6 Stephen Katz The Applied Use of Survey Results in Evangelizing Jewish Israelis 17 Stephen Katz What's in Jesus' Name according to Matthew? 23 Kai Kjaer-Hansen What Can We Know about Jesus, and How Can We Know It? 32 Michael J. Wilkins Is It Kosher to Substitute Jesus into God's Place? 41 Darrell Bock Christological Observations within Yeshua Judaism 51 Gershon Nerel Blessed and a Blessing 63 Mike Moore First "Organized" Bible-work in 19th Century Jerusalem, Part X: John 69 Nicolayson and Samuel Farman in Jerusalem in 1831 Kai Kjaer-Hansen Book Review: Evangelicals and Israel: The Story of American Christian 76 Zionism (Stephen Spector) Richard A. Robinson Book Review: Restoring Israel - 200 Years of the CMJ Story (Kelvin Crombie) 78 Bodil F. Skjøtt News from the Israeli Scene 80 John Sode-Woodhead Mishkan issue 59, 2009 Published by Pasche Institute of Jewish Studies, a ministry of Criswell College, in cooperation with Caspari Center for Biblical and Jewish Studies and Christian Jew Foundation Ministries Copyright © Pasche Institute of Jewish Studies Graphic design: Diana Cooper Cover design: Heidi Tohmola Printed by Evangel Press, 2000 Evangel Way, Nappanee, IN 46550, USA ISSN 0792-0474 ISBN-13: 978-0-9798503-7-0 ISBN-10: 0-9798503-7-1 Editor in Chief: Jim R. -

Jews, Church & Civilization

www.Civilization1000.com Contemporary Jewish Museum San Francisco Architect: Daniel Libeskind VII VII 1956 CE - 2008 CE 7-volume set $100 / New see inside for Paradigm TM barcode scan Matrix New Paradigm Matrix 21st CENTURY PUBLISHING www.NewParadigmMatrix.com David Birnbaum’s Jews, Church & Civilization is a uniquely distinctive work on the extraordinary historical odyssey of the Jews. New Paradigm Matrix TM Birnbaum starts not with Abraham, but somewhat more adventurously, with the ‘origin’ of the cosmos as we know it. The au- thor uniquely places the Jewish journey within the context of Western and Asian history and advance. Playing–out themes of the ebbs–and–flows of empires, discovery and exploration, scien- tific, intellectual and artistic advance, Birn- baum injects history with spice, flavor, irony and texture. Jewish and rabbinic scholarship are given not inconsiderable attention. The author of the iconic Summa Metaphysica philosophy se- ries articulates the flow of Jewish intellectual advance winding through the centuries – in the context of world and Jewish history. A feast for the mind and the soul. * * * 21st CENTURY PUBLISHING New Paradigm Matrix Publishing About the Author David Birnbaum is known globally as “the architect of Poten- tialism Theory” – a unified philosophy/cosmology/metaphysics. The paradigm-challenging theory is delineated in Birnbaum’s 3-volume Summa Metaphysica series (1988, 2005, 2014). A riposte to Summa Theologica of (St.) Thomas Aquinas, the Birnbaum treatise (see PotentialismTheory.com) challenges both the mainstream Western philosophy of Aristotelianism and the well-propped-up British/atheistic cosmology of Randomness (see ParadigmChallenge.com). The focus of over 150 reviews and articles (see SummaCoverage.com), a course text at over 15 insti- tutions of higher learning globally (see SummaCourseText.com), Summa Metaphysica was the focus of an international academic conference on Science & Religion April 16-19, 2012 (see BardCon- ference.com). -

Front Matter

Cambridge University Press 0521652073 - The Cambridge Companion to Medieval Jewish Philosophy Edited by Daniel H. Frank and Oliver Leaman Frontmatter More information the cambridge companion to MEDIEVAL JEWISH PHILOSOPHY From the ninth to the fifteenth centuries Jewish thinkers livingin Islamic and Christian lands philosophized about Judaism. Influenced first by Islamic theological speculation and the great philosophers of classical antiquity, and then in the late medieval period by Christian Scholasticism, Jewish philosophers and scientists reflected on the nature of lan- guage about God, the scope and limits of human understand- ing, the eternity or createdness of the world, prophecy and divine providence, the possibility of human freedom, and the relationship between divine and human law. Though many viewed philosophy as a dangerous threat, others incorporated it into their understandingof what it is to be a Jew. This Companion presents all the major Jewish thinkers of the period, the philosophical and non-philosophical contexts of their thought, and the interactions between Jewish and non- Jewish philosophers. It is a comprehensive introduction to a vital period of Jewish intellectual history. Daniel H. Frank is Professor of Philosophy and Director of the Judaic Studies Program at the University of Kentucky. Amongrecent publications are History of Jewish Philosophy (edited with Oliver Leaman, 1997), The Jewish Philosophy Reader (edited with Oliver Leaman and Charles Manekin, 2000), and revised editions of two Jewish philosophical clas- sics, Maimonides’ Guide of the Perplexed (1995) and Saadya Gaon’s Book of Doctrines and Beliefs (2002). Oliver Leaman is Professor of Philosophy and Zantker Profes- sor of Judaic Studies at the University of Kentucky. -

Varieties of Haskalah: Sabato Morais's Program of Sephardi Rabbinic Humanism in Victorian America

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Scholarship at Penn Libraries Penn Libraries 2004 Varieties of Haskalah: Sabato Morais's Program of Sephardi Rabbinic Humanism in Victorian America Arthur Kiron University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/library_papers Part of the Jewish Studies Commons Recommended Citation Kiron, A. (2004). Varieties of Haskalah: Sabato Morais's Program of Sephardi Rabbinic Humanism in Victorian America. Retrieved from https://repository.upenn.edu/library_papers/73 Suggested Citation: Kiron, Arthur. "Varieties of Haskalah: Sabato Morais's Program of Sephardi Rabbinic Humanism in Victorian America" in Renewing the past, reconfiguring Jewish culture : from al-Andalus to the Haskalah. Ed. Ross Brann and Adam Sutcliffe. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/library_papers/73 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Varieties of Haskalah: Sabato Morais's Program of Sephardi Rabbinic Humanism in Victorian America Disciplines Arts and Humanities | Jewish Studies Comments Suggested Citation: Kiron, Arthur. "Varieties of Haskalah: Sabato Morais's Program of Sephardi Rabbinic Humanism in Victorian America" in Renewing the past, reconfiguring Jewish culture : from al-Andalus to the Haskalah. Ed. Ross Brann and Adam Sutcliffe. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004. This book chapter is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/library_papers/73 JEWISH CULTURE AND CONTEXTS Renewing the Past, Published in association with the Center for Advanced Judaic Studies of the University of Pennsylvania Reconfiguring Jewish David B. Ruderman, Series Editor Culture Advisory Board Richard I. Cohen Moshe Idel Deborah Dash Moore Ada Rapoport-Albert From al-Andalus to the Haskalah David Stern A complete list of books in the series is available from the publisher. -

Barnah (Tel-Aviv), Fast. 47, Jan., Pp. 48-53; 48, June, Pp. 65-75; 49, Sep., Pp

1946 1. 'Al ha-tey'atron esel ha-LAravim,' Barnah (Tel-Aviv), fast. 47, Jan., pp. 48-53; 48, June, pp. 65-75; 49, Sep., pp. 48-60; 50, Jan., pp. 107-115. 1947 2. `Ha-Aqademiyya al-Azhar,' Bi-Terent (Tel-Aviv), 3, Mar., pp. 58-61. 3. `Drarnah bevratit binnakhit be-'aravit,' Banzah, 51, May, pp. 33-34. 4. `Muhammad and Zamenhor(review), Davar (Tel-Aviv), 15 Aug., p. 7. 5. 'Ha-tey'airon ha- aravi b6-Eres Yisra' el ba-shanah ha-abanina: Barnah, 52, Dec., p. 43. 1948 6. `Shadow plays in the Near East,' Edoth (Jerusalem), Di, 1-2, Oct.-Jan., pp. xxiii -lxiv. 7. ‘MabazAit ha-s6laffm ba-MizraI ha-Qarov,' ibid., pp. 33-72 (Hebrew translation of no. 6). 1949 8. 'G. Fucito, I rnerrati del Wcino Oriente' (review), Ha-Mizrah He- Iadash (Jerusalem), 1, 1, pp. 88-89. 1950 9. Index to Ha-Mizrah He-l-fadash, I (in Hebrew), ibid., I, 1949-1950, pp. 353-378. 10. 'RD. Matthews and Matta Akrawi, Education in Arab countries of the Near East' (review), The Palestine Post (Jerusalem), 7 Apr., p. 8. 11. `Sh. Gordon, Ha-'61arn ha- `aravr (review), Davar, 28 Apr., p. 5. 12. Teadf5t min ha-arkhiyyonirn ha-Btritiyyim 'al nisyon ha-hityashsheviit ha-yehricift b6-Midyan,' Shrvat Siyydn — Sefer ha-shanah shel ha- Siyylinut (Jerusalem), 1, pp. 169-178. 1951 13. 'Abraham Galant6, L'adoption des caracteres latins dans la langue hibrarque signifie sa dislocation' (review), Qiryat Sefer (Jerusalem), XXVII, 1950-1951, p. 212. 14. 'Li-she'elat reshito steel ha-tey'atron be-Misrayim,' Ha•Mizrah He- &dash, II, 8, pp.