Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Number 2, Spring 2004

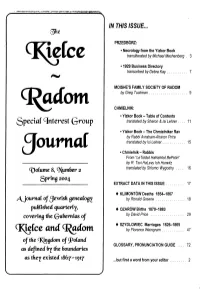

IN THIS ISSUE... PRZEDBÔRZ: • Necrology from the Yizkor Book transliterated by Michael Meshenberg . 3 • 1929 Business Directory transcribed by Debra Kay 7 MOISHE'S FAMILY SOCIETY OF RADOM by Greg Tuckman 9 CHMIELNIK: • Yizkor Book - Table of Contents Speciaf interest Group translated by Sharon & Isi Lehrer.... 11 • Yizkor Book - The Chmielniker Rav by Rabbi Avraham-Aharon Price ^journal translated by Isi Lehrer 15 •Chmielnik-Rabbis From "LeToldot HaKehilot BePolin" by R. Tsvi HaLevy Ish Hurwitz 8, (]>{um6er 2 translated by Shlomo Wygodny 16 gpring 2004 EXTRACT DATA IN THIS ISSUE 17 • KLIMONTÔW Deaths 1854-1867 ^\ journaf oj £Jewish geneafog^ by Ronald Greene 18 puBfishetf quarterly, • OZARÔW Births 1870-1883 covering the (JuBernias oj by David Price 29 ancf • SZYDLOWIEC Marriages 1826-1865 of the ^Kingdom oftpoland by Florence Weingram 47 as defined 6^ the Boundaries GLOSSARY, PRONUNCIATION GUIDE .... 72 as they existed 1867-1917 ...but first a word from your editor 2 Kielce-Radom SIG Journal Volume 8, Number 2 Spring 2004 ... but first a word from our editor In this issue, we have information about the towns of Przedbôrz and Chmielnik. For Przedbôrz - a transliteration of the Special (Interest GrouP names of the Holocaust martyrs from the 1977 Przedbôrz Yizkor Book Przedborz - 33 shanim; and a transcript of the Przedbôrz cjournaf entries from the 1929 Polish Business Directory. ISSN No. 1092-8006 For Chmielnik - a translation of the extensive Table of Contents and a short article from the 1960 Yizkor Book Pinkas Published quarterly, Chmielnik: Yisker bukh noch der Khorev-Gevorener Yidisher in January, April, July and October, by the Kehile; and an article about Chmielnik rabbis translated from KIELCE-RADOM LeToldot HaKehilot BePolin. -

Parashat Korach 5773 June 8, 2013

Parashat Korach 5773 June 8, 2013 This week’s Dvar Tzedek takes the form of an interactive text study. We hope that you’ll use this text study to actively engage with the parashah and contemporary global justice issues. Consider using this text study in any of the following ways: • Learn collectively. Discuss it with friends, family or colleagues. Discuss it at your Shabbat table. • Enrich your own learning. Read it as you would a regular Dvar Tzedek and reflect on the questions it raises. • Teach. Use the ideas and reactions it sparks in you as the basis for your own dvar Torah. Please take two minutes to share your thoughts on this piece by completing this feedback form . Introduction Parashat Korach opens with a scene of intense political drama in which a coalition of disgruntled Israelites challenges Moses and Aaron’s leadership. An analysis of this rebellion and the motivations of its leaders provides an opportunity to explore questions of politics, power and leadership—our associations with them, why they are important and how we might be able to utilize them to achieve the justice that we seek for our communities and the world. The Torah describes the opening of the showdown between Korach’s coalition and Moses and Aaron, as follows: במדבר טז:א ד, ח יא Numbers 16:1 ---4, 8 ---111111 ַוִ ַ ח ֹקַרח, ֶ ִיְצָהר ֶ ְקָהת ֶ ֵלִוי; ְוָדָת Now Korach, son of Izhar son of Kohat son of Levi, took, along ַוֲאִביָר ְֵני ֱאִליב, ְואֹו ֶ !ֶ לֶת ְ נֵי —with Datan and Abiram sons of Eliab, and On son of Pelet ְרא%ֵב. -

I Am the Lord Your God, Who Brought You out from Under the Burdens of the Egyptians

Definition of Leadership "Leadership is a combination of strategy and character. If you must be without one, be without the strategy.“ - U.S. Army General H. Norman Schwarzkopf • God has chosen YOU to lead others • Your family needs YOU to be a spiritual leader • Your neighbors need YOU to be a spiritual leader • This church family needs YOU to be a spiritual leader Source: www.theamericanenterprise.org/taeja00c.htm Today… Can you trust God even in the pain? Then Moses said to the Lord, “Please, Lord, I have never been eloquent, neither recently nor in time past, nor since You have spoken to Your servant; for I am slow of speech and slow of tongue.” The Lord said to him, “Who has made man’s mouth? Or who makes him mute or deaf, or seeing or blind? Is it not I, the Lord? Now then go, and I, even I, will be with your mouth, and teach you what you are to say.” But he said, “Please, Lord, now send the message by whomever You will.” Exodus 4:10-13 But Moses said, “O Lord, please send someone else to do it.” (Exodus 4:13 NIV) But he said, “Oh, my Lord, please send someone else.” (Exodus 4:13 ESV) Are you ready to go when God calls? Then the anger of the Lord burned against Moses, and He said, “Is there not your brother Aaron the Levite? I know that he speaks fluently. And moreover, behold, he is coming out to meet you; when he sees you, he will be glad in his heart. -

Twenty Payment Life Policy the MASSACHUSETTS

II ADVERTISEMENTS A SAFE INVESTMENT FOR YOU Did you ever try to invest money safely? Experienced Financiers find this difficult: How much more so an inexperienced person. ...THE... Twenty Payment Life Policy (With its Combined Insurance and Endowment Features) ISSUED By THE MASSACHUSETTS MUTUAL LIFE INSURANCE COMPANY, OF SPRINGFIELD, MASS. is recommended to you as an investment, safe and profitable. The Policy is plain and simple and the privileges and values are stnted in plain figures that any one can read. It is a sure and systematic way of saving money for your own use or support in later years. Saving is largely a matter of habit. And the semi-compulsory feature cultivates that saving habit. Undir the contracts issued by the Massachusetts Mutual Life Insur- ance Company the protection afforded is unsurpassed. For further information address HOME OFFICE, Springfield, Mass., or New York Office, Empire Building, 71 Broadway. PHILADELPHIA OFFICE, - - - Philadelphia Bourse. BALTIMORE " 4 South Street. CINCINNATI " - Johnston Building. CHICAGO " Merchants Loan and Trust Building. ST. LOUIS " .... Century Building. ADVERTISEMENTS III 1851, 1901. The Phoenix Mutual Life Insurance Company, of Hartford, Connecticut, Issues Endowment Policies to either men or women, which (besides.giving Five other options) GUARANTEE when the Insured is Fifty, Sixty, or Seventy Years Old To Pay $1,500 in Cash for Every $1,000 of Insurance in force. Sample Policies, rates, and other information will be given on application to the Home Office. ¥ ¥ ¥ JONATHAN B. BUNCE, President. JOHN M. HOLCOMBE, Vice-President. CHARLES H. LAWRENCE, Secretary. MANAGERS: WEED & KENNEDY, New York. JULES GIRARDIN, Chicago. H. W. -

Moses Mendelssohn and the Jewish Historical Clock Disruptive Forces in Judaism of the 18Th Century by Chronologies of Rabbi Families

Moses Mendelssohn and The Jewish Historical Clock Disruptive Forces in Judaism of the 18th Century by Chronologies of Rabbi Families To be given at the Conference of Jewish Genealogy in London 2001 By Michael Honey I have drawn nine diagrams by the method I call The Jewish Historical Clock. The genealogy of the Mendelssohn family is the tenth. I drew this specifically for this conference and talk. The diagram illustrates the intertwining of relationships of Rabbi families over the last 600 years. My own family genealogy is also illustrated. It is centred around the publishing of a Hebrew book 'Megale Amukot al Hatora' which was published in Lvov in 1795. The work of editing this book was done from a library in Brody of R. Efraim Zalman Margaliot. The book has ten testimonials and most of these Rabbis are shown with a green background for ease of identification. The Megale Amukot or Rabbi Nathan Nata Shpiro with his direct descendants in the 17th century are also highlighted with green backgrounds. The numbers shown in the yellow band are the estimated years when the individuals in that generation were born. For those who have not seen the diagrams of The Jewish Historical Clock before, let me briefly explain what they are. The Jewish Historical Clock is a system for drawing family trees ow e-drmanfly 1 I will describe to you the linkage of the Mendelssohn family branch to the network of orthodox rabbis. Moses Mendelssohn 1729-1786 was in his time the greatest Jewish philosopher. He was one of the first Jews to write in a modern language, German and thus opened the doors to Jewish emancipation so desired by the Jewish masses. -

Miriyam Goldman OA Thesis 9Dec20.Pdf (247.7Kb)

The Living Stone: The Talmudic Paradox of the Seventh Month Gestational Viability vs. the Eighth Month Non-Viability Presented to the S. Daniel Abraham Honors Program in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Completion of the Program Stern College for Women Yeshiva University December 9, 2020 Miriyam A. Goldman Mentor: Rabbi Dr. Richard Weiss, Biology Table of Contents Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………………. 3 Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………….…. 4 Background to Pregnancy ……………………………………………………………………… 5 Talmudic Sources on the Dilemma ……………………………………………………………. 6 Meforshim on the Dilemma ……………………………………………………………………. 9 Secular Sources of the Dilemma ………………………………………………………………. 11 The Significance of Hair and Nails in Terms of Viability……………………………….……... 14 The Definition of Nefel’s Impact on Viability ……………………………………………….. 17 History of Premature Survival ………………………………………………………………… 18 Statistics on Prematurity ………………………………………………………………………. 19 Developmental Differences Between Seventh and Eighth Months ……………………….…. 20 Contemporary Talmudic Balance of the Dilemma..…………………………………….…….. 22 Contemporary Secular Balance of the Dilemma .……………………………………….…….. 24 Evaluation of Talmudic Accreditation …………………………………………………..…...... 25 Interviews with Rabbi Eitan Mayer, Rabbi Daniel Stein, and Rabbi Dr. Richard Weiss .…...... 27 Conclusion ………………………………………………………………………………….…. 29 References…..………………………………………………………………………………..… 34 2 Abstract This paper reviews the viability of premature infants, specifically the halachic status of those born in -

Dubrovnik Annals 2 (1998) Reviews Benjamin Arbel, Trading Nations

Dubrovnik Annals 2 (1998) 109 Reviews inquiry. A petty reader is likely to observe that his references and bibliography do not Benjamin Arbel, Trading Nations: Jews include works in some European languages, and Venetians in the Early Modern Eastern German for example. However, one must not Mediterranean. Leiden - New York - KOln, fail to discern a number of references in Eng 1995 lish, French, Italian as well as those of medi eval origin. His sources deserve even greater In the history of the Mediterranean, the credit. Arbel emerges here as a scholar wor year 1571 witnessed several most tragic thy of every praise, and an experienced ar events. On 5 August, Famagusta, the so chival researcher who has discovered a vereign city of Cyprus, was besieged by the number of valuable documents (see below) forces of the Ottoman Turks led by Sultan for which he should be given the most credit. Selim II, and on 7 October, the allied Chri A brief look at the structure of the study stian fleet under the command of Don Juan unfolds another of this author's qualities: he of Austria defeated the Turks in the naval takes great concern in human destinies. Arbel battle of Lepanto. While the great armies centers upon man, the individual, his mental clashed and the winds of war prevailed pattern and looks, and his environment. This throughout the European continent, an event aspect of his work is evident in the earlier of different nature took place in the Venetian studies,2 but also in his latest book, in which Republic: on 18 December it was decreed he inclines toward the medievalistics of the that all the Jews residing within the Repub day. -

The Greatest Mirror: Heavenly Counterparts in the Jewish Pseudepigrapha

The Greatest Mirror Heavenly Counterparts in the Jewish Pseudepigrapha Andrei A. Orlov On the cover: The Baleful Head, by Edward Burne-Jones. Oil on canvas, dated 1886– 1887. Courtesy of Art Resource. Published by State University of New York Press, Albany © 2017 State University of New York All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher. For information, contact State University of New York Press, Albany, NY www.sunypress.edu Production, Dana Foote Marketing, Fran Keneston Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Orlov, Andrei A., 1960– author. Title: The greatest mirror : heavenly counterparts in the Jewish Pseudepigrapha / Andrei A. Orlov. Description: Albany, New York : State University of New York Press, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2016052228 (print) | LCCN 2016053193 (ebook) | ISBN 9781438466910 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781438466927 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Apocryphal books (Old Testament)—Criticism, interpretation, etc. Classification: LCC BS1700 .O775 2017 (print) | LCC BS1700 (ebook) | DDC 229/.9106—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016052228 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 For April DeConick . in the season when my body was completed in its maturity, there imme- diately flew down and appeared before me that most beautiful and greatest mirror-image of myself. -

WHAT IS the ORIGIN of the LITVAK? the LEGACY of the GRAND DUCHY of LITHUANIA © Antony Polonsky 266

WHAT IS THE ORIGIN OF THE LITVAK? THE LEGACY OF THE GRAND DUCHY OF LITHUANIA © Antony Polonsky 266 By the end of the nineteenth century, the concept of the „Litvak" had become well- established in the Jewish world. Let me give a few literary examples. I will begin with two by non-Litvaks. In one of his „hasidic tales", „Tsvishn tsvay berg" (Be- tween Two Mountains), Yitshak Leibush Peretz describes the conflict between the hasidim and their mitnagdic opponents. He gives both sides their voice but clearly comes down on the side of the former. The story recounts the clash between the Brisker rov and his best pupil, who has left him to found a hasidic court. He ex- plains why: Your Torah, Rabbi, is nothing but law. It is without pity. Your Torah contains not a spark of compas- sion. And that is why it is without joy, without air to breathe. It is nothing but steel and iron-iron commandments, copper laws. It is a very refined Torah, suitable for scholars, for the select few. The Brisker rov was silent, so the rebbe continued: „Tell me, Rabbi, what have you got for ordinary people? For the woodchopper, the butcher, the tradesman, the simple man? And, most especially for the sinful man? What do you have to offer those who are not scholars?...". To convince the Brisker rov, the Bialer rebbe takes him to see his followers on Simkhat torah when they are transformed by the festival. This does not convince the Brisker rov. „We must say the afternoon prayer," the Brisker rov suddenly announced in his harsh voice-and eve- rything vanished. -

The Name of God the Golem Legend and the Demiurgic Role of the Alphabet 243

CHAPTER FIVE The Name of God The Golem Legend and the Demiurgic Role of the Alphabet Since Samaritanism must be viewed within the wider phenomenon of the Jewish religion, it will be pertinent to present material from Judaism proper which is corroborative to the thesis of the present work. In this Chapter, the idea about the agency of the Name of God in the creation process will be expounded; then, in the next Chapter, the various traditions about the Angel of the Lord which are relevant to this topic will be set forth. An apt introduction to the Jewish teaching about the Divine Name as the instrument of the creation is the so-called golem legend. It is not too well known that the greatest feat to which the Jewish magician aspired actually was that of duplicating God's making of man, the crown of the creation. In the Middle Ages, Jewish esotericism developed a great cycle of golem legends, according to which the able magician was believed to be successful in creating a o ?� (o?u)1. But the word as well as the concept is far older. Rabbinic sources call Adam agolem before he is given the soul: In the first hour [of the sixth day], his dust was gathered; in the second, it was kneaded into a golem; in the third, his limbs were shaped; in the fourth, a soul was irifused into him; in the fifth, he arose and stood on his feet[ ...]. (Sanh. 38b) In 1615, Zalman �evi of Aufenhausen published his reply (Jii.discher Theriak) to the animadversions of the apostate Samuel Friedrich Brenz (in his book Schlangenbalg) against the Jews. -

Israel at 60

Kol Hamevaser Contents Volume I, Issue 8 May 8, 2008 Staff Gilah Kletenik 3 Editorial Julian Horwitz 3 Letter to the Editor Continuing the Discussion Managing Editors Mattan Erder Ari Lamm 4 An Interview With Rabbi Dr. Norman Lamm Gilah Kletenik David Lasher R. Elchanan Adler 6 Deciphering a Spitting Image: To Live and to Learn Israel at 60 Associate Editor Yosef Bronstein 7 Shivat Tsiyon, Prophecy and Rav Kook Sefi Lerner Leah Kanner 8 Holy Land, Holy People Staff Writers Dr. Shmuel Schneider 9 Religious Circles in America and Their Attitude to Chava Chaitovsky the Study of Hebrew Noah Cheses Ari Lamm 11 An Interview with Rabbi Zevulun Charlop Ben Greenfield Dr. Ruth A. Bevan 15 A New Zionism Tikva Hecht Shimshon Ayzenberg 16 Moses Leib Lilienblum: Alex Ozar A Revised Legacy of an Early Zionist Ayol Samuels Gilah Kletenik 17 Mamlakhtiyut Shira Schwartz Yosef Lindell 18 Practical Zionism: R. Yitshak Yaakov Reines and the Beginnings of Mizrachi Interviewer Ari Lamm Aviva Stavsky 20 IDF: Peace-makers or Warmongers? Sabbath Ob- servers or Heretics? Copy Editors Zev Eleff 21 What They Were Really Saying at YU in ‘48 Shaul Seidler-Feller 22 Last Letter from Moshe Pearlstein Yishai Seidman Simeon Botwinick 22 A Visit to Har Ha-Bayit Art and Layout Editor Jaimie Fogel 23 The (Almost) Final Boarding Call Avi Feld About Kol Hamevaser Noah Cheses 23 The Future of the Zionist Enterprise Kol Hamevaser is a student publication supported by Kol Hamevaser is a magazine of Jewish thought dedicated to spark- The Commentator. Views expressed in Kol ing the discussion of Jewish issues on the Yeshiva University campus. -

Part 2: the First Partition of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, 1772 – Its Description and Depiction in Maps Andrew Kapochunas, Jersey City, New Jersey EN

Historical research article / Lietuvos istorijos tematika The Maps and Mapmakers that Helped Define 20th-Century Lithuanian Boundaries - Part 2: The First Partition of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, 1772 – Its Description and Depiction in Maps Andrew Kapochunas, Jersey City, New Jersey EN In the previous – and first – installment of this influence of Russia’s military on Empress Catherine II series, we established a geographical starting point for is primary: the dismemberment of the 11 provinces (vaivadijų) “…the military party was openly in favor of direct annexa- of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (Lietuvos Didžioji tions. They believed that Russia’s interests could best be Kunigaikštystė) by the Empire of Russia. My inten- served by seizing the territory of her neighbors on every tion was to then focus on the Russian administrative possible occasion. Chernyshev, the Vice-President of the War boundary changes of the lands they acquired. But, as I College, expressed this view when, at the new [as of 1762] reviewed the literature and maps describing the First, Empress Catherine’s council called to discuss the [1763] death 1772, Partition, I was struck by the disparate descrip- of the King of Poland [Augustus III], he proposed an invasion tions and cartographic depictions of that seemingly of Polish Livonia and the palatinates of Polotsk, Witebsk, and straight-forward event. I decided to present a sum- Mscislaw.”2 mary of that event and its immediate aftermath in the annexed regions. The next two articles, then, will Nine years later, those were the areas annexed – and cover the Second (1793) and Third (1795) Partitions.