The Attitude Towards Democracy in Medieval Jewishphilosophy*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Medieval Jewish Philosophy and Its Literary Forms'

H-Judaic Lawee on Hughes and Robinson, 'Medieval Jewish Philosophy and Its Literary Forms' Review published on Monday, March 16, 2020 Aaron W. Hughes, James T. Robinson, eds. Medieval Jewish Philosophy and Its Literary Forms. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2019. viii + 363 pp. $100.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-253-04252-1. Reviewed by Eric Lawee (Bar-Ilan University)Published on H-Judaic (March, 2020) Commissioned by Barbara Krawcowicz (Norwegian University of Science and Technology) Printable Version: http://www.h-net.org/reviews/showpdf.php?id=54753 Among the religious and intellectual innovations in which medieval Judaism abounds, none sparked controversy more than the attempt of certain rabbis and scholars to promote teachings of ancient Greek philosophy. Most notable, of course, was Moses Maimonides, the foremost legist and theologian of the age. Not only did he cultivate Greco-Arabic philosophy and science, but he also taught the radical proposition that knowledge of some of its branches was essential for a true understanding of revealed scripture and for worship of God in its purest form. As an object of modern scholarship, medieval philosophy has not suffered from a lack of attention. Since the advent of Wissenschaft des Judentums more than a century and half ago, studies have proliferated, whether on specific topics (e.g., theories of creation), leading figures (e.g., Saadiah Gaon, Judah Halevi, Maimonides), or the historical, religious, and intellectual settings in which Jewish engagements with philosophy occurred—first in -

אוסף מרמורשטיין the Marmorstein Collection

אוסף מרמורשטיין The Marmorstein Collection Brad Sabin Hill THE JOHN RYLANDS LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF MANCHESTER Manchester 2017 1 The Marmorstein Collection CONTENTS Acknowledgements Note on Bibliographic Citations I. Preface: Hebraica and Judaica in the Rylands -Hebrew and Samaritan Manuscripts: Crawford, Gaster -Printed Books: Spencer Incunabula; Abramsky Haskalah Collection; Teltscher Collection; Miscellaneous Collections; Marmorstein Collection II. Dr Arthur Marmorstein and His Library -Life and Writings of a Scholar and Bibliographer -A Rabbinic Literary Family: Antecedents and Relations -Marmorstein’s Library III. Hebraica -Literary Periods and Subjects -History of Hebrew Printing -Hebrew Printed Books in the Marmorstein Collection --16th century --17th century --18th century --19th century --20th century -Art of the Hebrew Book -Jewish Languages (Aramaic, Judeo-Arabic, Yiddish, Others) IV. Non-Hebraica -Greek and Latin -German -Anglo-Judaica -Hungarian -French and Italian -Other Languages 2 V. Genres and Subjects Hebraica and Judaica -Bible, Commentaries, Homiletics -Mishnah, Talmud, Midrash, Rabbinic Literature -Responsa -Law Codes and Custumals -Philosophy and Ethics -Kabbalah and Mysticism -Liturgy and Liturgical Poetry -Sephardic, Oriental, Non-Ashkenazic Literature -Sects, Branches, Movements -Sex, Marital Laws, Women -History and Geography -Belles-Lettres -Sciences, Mathematics, Medicine -Philology and Lexicography -Christian Hebraism -Jewish-Christian and Jewish-Muslim Relations -Jewish and non-Jewish Intercultural Influences -

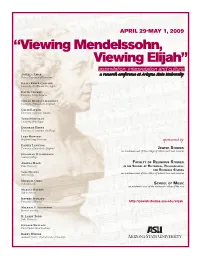

“Viewing Mendelssohn, Viewing Elijah”

APRIL 29-MAY 1, 2009 “Viewing Mendelssohn, Viewing Elijah” assimilation, interpretation and culture Ariella Amar a rreses eearcharch cconferenceonference atat ArizonaArizona StateState UniversityUniversity Hebrew University of Jerusalem Julius Reder Carlson University of California, Los Angeles David Conway University College London Sinéad Dempsey-Garratt University of Manchester, England Colin Eatock University of Toronto, Canada Todd Endelman University of Michigan Deborah Hertz University of California, San Diego Luke Howard Brigham Young University sponsored by Daniel Langton University of Manchester, England JEWISH STUDIES an academic unit of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences Jonathan D. Lawrence Canisius College Angela Mace FACULTY OF RELIGIOUS STUDIES Duke University IN THE SCHOOL OF HISTORICAL, PHILOSOPHICAL AND RELIGIOUS STUDIES Sara Malena Wells College an academic unit of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences Michael Ochs Ochs Editorial SCHOOL OF MUSIC an academic unit of the Herberger College of the Arts Marcus Rathey Yale University Jeffrey Sposato University of Houston http://jewishstudies.asu.edu/elijah Michael P. Steinberg Brown University R. Larry Todd Duke University Donald Wallace United States Naval Academy Barry Wiener Graduate Center, City University of New York Viewing Mendelssohn, Viewing Elijah: assimilation, interpretation and culture a research conference at Arizona State University / April 29 – May 1, 2009 Conference Synopsis From child prodigy to the most celebrated composer of his time: Felix Mendelssohn -

Encyclopedia Interrupta, Or Gale's Unfinished

Judaica Librarianship Volume 16/17 195-209 12-31-2011 Encyclopedia Interrupta, or Gale’s Unfinished: the Scandal of the EJ2 Barry D. Walfish [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://ajlpublishing.org/jl Part of the Bilingual, Multilingual, and Multicultural Education Commons, Information Literacy Commons, Jewish Studies Commons, and the Reading and Language Commons Recommended Citation Walfish, Barry D.. 2011. "Encyclopedia Interrupta, or Gale’s Unfinished: the Scandal of the EJ2." Judaica Librarianship 16: 195-209. doi:10.14263/2330-2976.1012. Encyclopedia Interrupta, or Gale’s Unfinished: the Scandal of the EJ2 Erratum On p. 203, the birthdate of Maimonides was corrected from 1038 to 1138. This review is available in Judaica Librarianship: http://ajlpublishing.org/jl/vol16/iss1/13 Reviews 195 text. To the extent that a rabbinic text is a window into rabbinic culture as well as the rabbis’ attitudes toward and interactions with the surrounding cul- ture(s), it is impossible to explain fully its broader significance until its cultural and ideological connotations have been explored. Here, too, one runs the risk of including so much in the discussion of a text that the focus of discourse moves away from the document itself towards a set of questions more properly belonging to other disciplines. However, the field of rabbinics has been insulat- ed from other academic disciplines longer and more completely than any other field of Jewish studies. Therefore it is crucial that we broaden our discus- sion of rabbinic texts to include the scholarship of those who have applied the tools and insights of disciplines other than philology to the study of rabbinic literature. -

Pentateuch Country: Italy Value: AUCTION Genre: Religion Year Published: 1475 Author: Rashi Why Important: the Pentateuch Are T

Pentateuch Country: Italy Value: AUCTION Genre: Religion Year Published: 1475 Author: Rashi Why Important: The Pentateuch are the first five books of the Bible, sacred to both Jews and Christians. Moses is credited with writing Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy. Arba’ Turim Country: Italy Value: AUCTION Genre: Religion Year Published: 1475 Author: Rabbi Jacob ben Asher Why Important: The first book of Jewish religious law, originally composed in manuscript in the late 13th or early 14th century. Job Country: Italy Value: AUCTION Genre: Religion Year Published: 1477 Author: Levi ben Gershon Why Important: Levin ben Gershon lived in the late 13th and early 14th century as a scientist, philosopher, and doctor in France. He is famous as a commentator; this book is a commentary on Job. Nofet Zufim Country: Italy Value: AUCTION Also Known As: The Honeycomb’s Flow Genre: Language Year Published: 1475-1480 Author: Judah ben Jehiel Refe (Judah Messer Leon) Why Important: Jewish Italian scholar’s book on Renaissance rhetoric; also the first Hebrew book of a living author to be printed. Il Commodo comedia di Antonio Landi Country: Italy Value: AUCTION Also Known As: The Server?: Comedy of Antonio Landi Genre: History Year Published: 1539 Author: Pier Francesco Giambullari Why Important: Account of the wedding in Florence of Cosimo l de’ Medici and Eleanora of Toledo. Breve descrizione delle pomp funereale fatta nelle essquie del serenmissio D. Francesco Medici II Country: Italy Value: AUCTION Also Known As: Brief Description of the funeral of D. Francesco Medici II Genre: History Year Published: 1587 Author: Giovanni Vittorio Soderini Why Important: Account of the Funeral in Florence of Francesco l de’ Medici. -

Sixteenth-Century Hebrew Books in the Library of Congress

Sixteenth-Century Hebrew Books at the Library of Congress A Finding Aid פה Washington D.C. June 18, 2012 ` Title-page from Maimonides’ Moreh Nevukhim (Sabbioneta: Cornelius Adelkind, 1553). From the collections of the Hebraic Section, Library of Congress, Washington D.C. i Table of Contents: Introduction to the Finding Aid: An Overview of the Collection . iii The Collection as a Testament to History . .v The Finding Aid to the Collection . .viii Table: Titles printed by Daniel Bomberg in the Library of Congress: A Concordance with Avraham M. Habermann’s List . ix The Finding Aid General Titles . .1 Sixteenth-Century Bibles . 42 Sixteenth-Century Talmudim . 47 ii Sixteenth-Century Hebrew Books in the Library of Congress: Introduction to the Finding Aid An Overview of the Collection The art of Hebrew printing began in the fifteenth century, but it was the sixteenth century that saw its true flowering. As pioneers, the first Hebrew printers laid the groundwork for all the achievements to come, setting standards of typography and textual authenticity that still inspire admiration and awe.1 But it was in the sixteenth century that the Hebrew book truly came of age, spreading to new centers of culture, developing features that are the hallmark of printed books to this day, and witnessing the growth of a viable book trade. And it was in the sixteenth century that many classics of the Jewish tradition were either printed for the first time or received the form by which they are known today.2 The Library of Congress holds 675 volumes printed either partly or entirely in Hebrew during the sixteenth century. -

Front Matter

Cambridge University Press 0521652073 - The Cambridge Companion to Medieval Jewish Philosophy Edited by Daniel H. Frank and Oliver Leaman Frontmatter More information the cambridge companion to MEDIEVAL JEWISH PHILOSOPHY From the ninth to the fifteenth centuries Jewish thinkers livingin Islamic and Christian lands philosophized about Judaism. Influenced first by Islamic theological speculation and the great philosophers of classical antiquity, and then in the late medieval period by Christian Scholasticism, Jewish philosophers and scientists reflected on the nature of lan- guage about God, the scope and limits of human understand- ing, the eternity or createdness of the world, prophecy and divine providence, the possibility of human freedom, and the relationship between divine and human law. Though many viewed philosophy as a dangerous threat, others incorporated it into their understandingof what it is to be a Jew. This Companion presents all the major Jewish thinkers of the period, the philosophical and non-philosophical contexts of their thought, and the interactions between Jewish and non- Jewish philosophers. It is a comprehensive introduction to a vital period of Jewish intellectual history. Daniel H. Frank is Professor of Philosophy and Director of the Judaic Studies Program at the University of Kentucky. Amongrecent publications are History of Jewish Philosophy (edited with Oliver Leaman, 1997), The Jewish Philosophy Reader (edited with Oliver Leaman and Charles Manekin, 2000), and revised editions of two Jewish philosophical clas- sics, Maimonides’ Guide of the Perplexed (1995) and Saadya Gaon’s Book of Doctrines and Beliefs (2002). Oliver Leaman is Professor of Philosophy and Zantker Profes- sor of Judaic Studies at the University of Kentucky. -

Varieties of Haskalah: Sabato Morais's Program of Sephardi Rabbinic Humanism in Victorian America

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Scholarship at Penn Libraries Penn Libraries 2004 Varieties of Haskalah: Sabato Morais's Program of Sephardi Rabbinic Humanism in Victorian America Arthur Kiron University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/library_papers Part of the Jewish Studies Commons Recommended Citation Kiron, A. (2004). Varieties of Haskalah: Sabato Morais's Program of Sephardi Rabbinic Humanism in Victorian America. Retrieved from https://repository.upenn.edu/library_papers/73 Suggested Citation: Kiron, Arthur. "Varieties of Haskalah: Sabato Morais's Program of Sephardi Rabbinic Humanism in Victorian America" in Renewing the past, reconfiguring Jewish culture : from al-Andalus to the Haskalah. Ed. Ross Brann and Adam Sutcliffe. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/library_papers/73 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Varieties of Haskalah: Sabato Morais's Program of Sephardi Rabbinic Humanism in Victorian America Disciplines Arts and Humanities | Jewish Studies Comments Suggested Citation: Kiron, Arthur. "Varieties of Haskalah: Sabato Morais's Program of Sephardi Rabbinic Humanism in Victorian America" in Renewing the past, reconfiguring Jewish culture : from al-Andalus to the Haskalah. Ed. Ross Brann and Adam Sutcliffe. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004. This book chapter is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/library_papers/73 JEWISH CULTURE AND CONTEXTS Renewing the Past, Published in association with the Center for Advanced Judaic Studies of the University of Pennsylvania Reconfiguring Jewish David B. Ruderman, Series Editor Culture Advisory Board Richard I. Cohen Moshe Idel Deborah Dash Moore Ada Rapoport-Albert From al-Andalus to the Haskalah David Stern A complete list of books in the series is available from the publisher. -

Review of Judah Messer Leon and Issac Rabinowitz, the Book of the Honeycomb's Flow (Sepher Nopheth Suphim) David B

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Departmental Papers (History) Department of History 1985 Review of Judah Messer Leon and Issac Rabinowitz, The Book of the Honeycomb's Flow (Sepher Nopheth Suphim) David B. Ruderman University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.upenn.edu/history_papers Part of the European History Commons, History of Religion Commons, Intellectual History Commons, Jewish Studies Commons, Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons, and the Rhetoric Commons Recommended Citation Ruderman, D. B. (1985). Review of Judah Messer Leon and Issac Rabinowitz, The Book of the Honeycomb's Flow (Sepher Nopheth Suphim). The Sixteenth Century Journal, 16 (1), 147-148. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2540945 At the time of this publication, Dr. Ruderman was affiliated with Yale University, but he is now a faculty member of the University of Pennsylvania. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. http://repository.upenn.edu/history_papers/54 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Review of Judah Messer Leon and Issac Rabinowitz, The Book of the Honeycomb's Flow (Sepher Nopheth Suphim) Abstract Published as early as 1475-76, Judah Messer Leon's Hebrew rhetorical handbook, The Book of the Honeycomb's Flow, is clearly one of the most notable examples of the interaction between the Italian Renaissance and Jewish culture. Messer Leon, an accomplished physician, Aristotelian scholar, and rabbinic luminary, lived in a number of cities in north-central Italy during the second half of the fifteenth century. Having already composed Hebrew educational treatises on grammar and logic, he now introduced to his students the third part of the medieval trivium, the study of rhetoric, and placed it squarely at the center of his novel curriculum of Jewish studies. -

Mass Conversion and Genealogical Mentalities: Jews and Christians in Fifteenth-Century Spain*

MASS CONVERSION AND GENEALOGICAL MENTALITIES: JEWS AND CHRISTIANS IN FIFTEENTH-CENTURY SPAIN* It is both well known and worthy of note that Sephardim (that is, the descendants of Jews expelled from Spain) and Spaniards shared an unusually heightened concern with lineage and genea- logy in the early modern period. The Spanish obsession with hidalguia, Gothic descent, and purity of blood has long constituted a stereotype. Think only of Don Juan's father, mockingly por- trayed by Lord Byron: 'His father's name was Jos6 - Don, of course, / A true Hidalgo, free from every stain / Of Moor or Hebrew blood, he traced his source / Through the most Gothic gentlemen of Spain'.1 The Sephardim, too, were criticized on this score almost from the moment of exile. The (Ashkenazic) Italian David ben Judah Messer Leon, for example, ridiculed the eminent exile Don Isaac Abarbanel's claims to royal pedigree, scoffing that Abarbanel 'made of himself a Messiah with his claims to Davidic descent'.2 That the exiles' emphasis on lineage flourished nonetheless is evident, not only in the splendid armorial bearings of Sephardic * I took up this topic in response to an invitation from the History Department of the University of California, Los Angeles. Its revision was stimulated by comments from the audience there, as well as at Indiana University, at the Rutgers Center for Historical Analysis, and at Maurice Kriegel's seminar at the Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales, Paris. Sara Lipton urged me to rethink my arguments, Eliezer Lazaroff and Talya Fishman helped me navigate the seas of rabbinics, and a Mellon Fellowship at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences at Stanford provided the calm in which to do so. -

Studia Humana Volume 6:2 (2017) Contents Preface. Philosophy And

Studia Humana Volume 6:2 (2017) Contents Preface. Philosophy and History of Talmudic Logic (Andrew Schumann)………………………………………………………………………………….3 Epistemic Disagreement and ’Elu We’Elu (Joshua Halberstam)…………………………………………………………………………………7 Developments in the Syntax and Logic of the Talmudic Hermeneutic Kelal Uferaṭ Ukelal (Michael Chernick)…………………………………………………………………..………....…...17 Medieval Judaic Logic and the Scholastic One in the 14th – 15th Centuries Provence and Italy: a Comparison of the Logical Works by Rav Hezekiah bar Halafta (First Half of the 14th Century) and Rav Judah Messer Leon (Second Half of the 15th Century) (Mauro Zonta)……….…………………………………………………………...............................37 Suspending New Testament: Do the Two Talmuds Belong to Hermeneutics of Texts? (Sergey Dolgopolski)……………………………………………………….……………...………..46 The Genesis of Arabic Logical Activities: From Syriac Rhetoric and Jewish Hermeneutics to al-Šāfi‘y’s Logical Techniques (Hany Azazy)…………………………………………………………………...……………….…..65 Connecting Sacred and Mundane: From Bilingualism to Hermeneutics in Hebrew Epitaphs (Michael Nosonovsky)………………………………………………………………………………96 Using Lotteries in Logic of Halakhah Law. The Meaning of Randomness in Judaism (Ely Merzbach)……………………………………………………………………………….…....107 Probabilistic Foundations of Rabbinic Methods for Resolving Uncertainty (Moshe Koppel)…………………………………………………………………………………....116 On the Babylonian Origin of Symbolic Logic (Andrew Schumann)………………………………………………………………………….……126 Studia Humana Volume 6:2 (2017), pp. 3—6 DOI: 10.1515/sh-2017-0007 Preface. Philosophy and History of Talmudic Logic Andrew Schumann University of Information Technology and Management in Rzeszow, Rzeszow, Poland e-mail: [email protected] Abstract: This volume contains the papers presented at the Philosophy and History of Talmudic Logic Affiliated Workshop of Krakow Conference on History of Logic (KHL2016), held on October 27, 2016, in Krakow, Poland. Keywords: Talmudic logic, Judaism, halakhah, Judaic laws, kelal uferaṭ ukelal, heqqeš, qal wa-ḥomer. -

Between Court and Call: Catalan Humanism and Hebrew Letters1

Ryan Szpiech Between Court and Call: Catalan Humanism and Hebrew Letters1 Ryan Szpiech University of Michigan When Catalan poet Solomon de Piera, already over seventy years old, converted from Judaism to Christianity around 1410, his many sorrows only increased. Old, ill, and alone, he sent a poem to his former student, Vidal Benveniste Ben Labi, claiming that his only legacy would be through his poems. When de Piera compared his soul to the forgotten prostitute of Tyre, who in Isaiah 23:16, is told to “skillfully play many songs so that you be remembered,” Benveniste responded with a poem in turn, mockingly urging him to “Rise, whore, take up your lyre—and sing your songs if you can, for hire.” (Vardi 1:4 and 3:14; Cole 303 and 307).2 In this bitter exchange, poetic innovation and clever allusion serve as the weapons in this battle over conversion, waged in the chaotic years between the mass Jewish conversions of 1391 and the aggressive preaching blitz of Dominican friar Vicente Ferrer two decades after that led to even more conversions. This literary response to the changing atmosphere of the crown of Aragon in the early fifteenth century, both within and beyond its calls (Jewish neighborhoods), might be taken as a sign of the resurgence of Hebrew writing that also included the masterful poetry of Solomon Bonafed and Vidal de la Cavallería. Many have in fact been tempted to call the fifteenth century a renaissance in Sephardic literature, insofar as it marks a wave of rich new poetic activity after a period of stagnation and conventionality.