Morris Matters Vol 27 Issue 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newsletter 59

SQUIRE: BRIAN TASKER 6 ROOPERS, SPELDHURST, TUNBRIDGE WELLS, KENT, TN3 0QL TEL: 01892 862301 E-mail: [email protected] BAGMAN: CHARLIE CORCORAN 70, GREENGATE LANE, BIRSTALL, LEICESTER, LEICS LE4 3DL TEL: 01162 675654 E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] TREASURER: STEVE ADAMSON BFB 12, FLOCKTON ROAD, EAST BOWLING, BRADFORD, WEST YORKSHIRE BD4 7RH TEL: 01274 773830 E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] The Newsletter No.59 December 2008 The highlights of this Newsletter are: Page Massed Dances and their music 2 Annual Representatives’ Meeting 3 Information about Chris Harris’ “Kemps Jig” 4 ARM Agenda (and advance request for Reports) 6 Joint Morris Organisations: Nottingham Revels 28th March 2009 8 EFDSS News 8 Francis Shergold (1919-2008) A Tribute by Paul Reece 10 Cultural Olympiad 11 2009 Meetings of Morris Ring 11 Treasurer’s ramblings 11 Who’s going to which meeting? 12 Saddleworth Rushcart 2009 12 Jigs Instructional 2009 13 2009 Rapper and Longsword Tournaments 13 Redcar Sword Dancers triumphant again 14 Morris in the Media – Marks for trying? 14 Future Dates 16 Application Forms: Jigs Instructional 19 Morris Ring Meetings 20 Morris Ring Newsletter No 59 December 2008 Page 1 of 20 THE MORRIS RING IS THE NATONAL ASSOCIATION OF MEN’S MORRIS & SWORD DANCE CLUBS Music for Massed Dancing. Following the article in Newsletter No. 58 Harry Winstone, of Kemp's Men, contacted Brian Tasker, Squire of the Morris Ring, and suggested that we need to provide some indication of the tunes to be used. His comment was “50 musicians all playing their own versions. -

Sound Recording in the British Folk Revival: Ideology, Discourse and Practice, 1950–1975

Sound recording in the British folk revival: ideology, discourse and practice, 1950–1975 Matthew Ord Submitted in fulfilment of the degree of PhD International Centre for Music Studies Newcastle University March 2017 Abstract Although recent work in record production studies has advanced scholarly understandings of the contribution of sound recording to musical and social meaning, folk revival scholarship in Britain has yet to benefit from these insights. The revival’s recording practice took in a range of approaches and contexts including radio documentary, commercial studio productions and amateur field recordings. This thesis considers how these practices were mediated by revivalist beliefs and values, how recording was represented in revivalist discourse, and how its semiotic resources were incorporated into multimodal discourses about music, technology and traditional culture. Chapters 1 and 2 consider the role of recording in revivalist constructions of traditional culture and working class communities, contrasting the documentary realism of Topic’s single-mic field recordings with the consciously avant-garde style of the BBC’s Radio Ballads. The remaining three chapters explore how the sound of recorded folk was shaped by a mutually constitutive dialogue with popular music, with recordings constructing traditional performance as an authentic social practice in opposition to an Americanised studio sound equated with commercial/technological mediation. As the discourse of progressive rock elevated recording to an art practice associated with the global counterculture, however, opportunities arose for the incorporation of rock studio techniques in the interpretation of traditional song in the hybrid genre of folk-rock. Changes in studio practice and technical experiments with the semiotics of recorded sound experiments form the subject of the final two chapters. -

14302 76969 1 1>

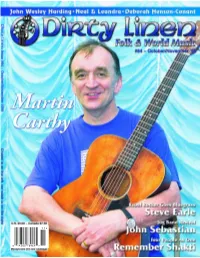

11> 0514302 76969 establishment,” he hastened to clarify. “I wish it were called the Legion of Honour, but it’s not.” Still in all, he thinks it’s good for govern- M artin C arthy ments to give cultural awards and is suitably honored by this one, which has previously gone to such outstanding folk performers as Jeannie Robertson. To decline under such circum- stances, he said, would have been “snotty.” Don’t More importantly, he conceives of his MBE as recognition he shares with the whole Call Me folk scene. “I’ve been put at the front of a very, very long queue of people who work hard to make a folk revival and a folk scene,” he said. Sir! “All those people who organized clubs for nothing and paid you out of their own pocket, and fed you and put you on the train the next morning, and put you to bed when you were drunk! What [the government is] doing, is taking notice of the fact that something’s going on for the last more than 40 years. It’s called the folk revival. They’ve ignored it for that long. And someone has suddenly taken notice, and that’s okay. A bit of profile isn’t gonna hurt us — and I say us, the plural, for the folk scene — isn’t gonna hurt us at all.” In the same year as Carthy’s moment of recognition, something happened that did hurt the folk scene. Lal Waterson, Carthy’s sister-in- law, bandmate, near neighbor and close friend, died of cancer. -

Topic Records 80Th Anniversary Start Time: 8Pm Running Time: 2 Hours 40 Minutes with Interval

Topic Records 80th Anniversary Start time: 8pm Running time: 2 hours 40 minutes with interval Please note all timings are approximate and subject to change Martin Aston discusses the history behind the world’s oldest independent label ahead of this collaborative performance. When Topic Records made its debut in 1939 with Paddy Ryan’s ‘The Man That Waters The Workers’ Beer’, an accordion-backed diatribe against capitalist businessmen who underpay their employees, it’s unlikely that anyone involved was thinking of the future – certainly not to 2019, when the label celebrates its 80th birthday. In any case, the future would have seemed very precarious in 1939, given the outbreak of World War II, during which Topic ceased most activity (shellac was particularly hard to source). But post-1945, the label made good on its original brief: ‘To use popular music to educate and inform and improve the lot of the working man,’ explains David Suff, the current spearhead of the world’s oldest independent label – and the undisputed home of British folk music. Tonight at the Barbican (where Topic held their 60th birthday concerts), musical director Eliza Carthy – part of the Topic recording family since 1997, though her parents Norma Waterson and Martin Carthy have been members since the sixties and seventies respectively - has marshalled a line-up to reflect the passing decades, which hasn’t been without its problems. ‘We have far too much material, given it’s meant to be a two-hour show!’ she says. ‘It’s impossible to represent 80 years – you’re talking about the left-wing leg, the archival leg, the many different facets of society - not just communists but farmers and factory workers - and the folk scene in the Fifties, the Sixties, the Seventies.. -

Off the Beaten Track

Off the Beaten Track To have your recording considered for review in Sing Out!, please submit two copies (one for one of our reviewers and one for in- house editorial work, song selection for the magazine and eventual inclusion in the Sing Out! Resource Center, our multimedia, folk-related archive). All recordings received are included in Publication Noted (which follows Off the Beaten Track). Send two copies of your recording, and the appropriate background material, to Sing Out!, P.O. Box 5460 (for shipping: 512 E. Fourth St.), Bethlehem, PA 18015, Attention Off The Beaten Track. Sincere thanks to this issues panel of musical experts: Roger Dietz, Richard Dorsett, Tom Druckenmiller, Mark Greenberg, Victor K. Heyman, Stephanie P. Ledgin, John Lupton, Andy Nagy, Angela Page, Mike Regenstreif, Peter Spencer, Michael Tearson, Rich Warren, Matt Watroba, Elijah Wald, and Rob Weir. liant interpretation but only someone with not your typical backwoods folk musician, Jodys skill and knowledge could pull it off. as he studied at both Oberlin and the Cin- The CD continues in this fashion, go- cinnati College Conservatory of Music. He ing in and out of dream with versions of was smitten with the hammered dulcimer songs like Rhinordine, Lord Leitrim, in the early 70s and his virtuosity has in- and perhaps the most well known of all spired many players since his early days ballads, Barbary Ellen. performing with Grey Larsen. Those won- To use this recording as background derful June Appal recordings are treasured JODY STECHER music would be a mistake. I suggest you by many of us who were hearing the ham- Oh The Wind And Rain sit down in a quiet place, put on the head- mered dulcimer for the first time. -

The Watersons the Definitive Collection Mp3, Flac, Wma

The Watersons The Definitive Collection mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Folk, World, & Country Album: The Definitive Collection Country: UK Released: 2003 Style: Folk MP3 version RAR size: 1203 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1609 mb WMA version RAR size: 1410 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 881 Other Formats: AHX AUD MP4 AU MP1 MMF DTS Tracklist 1 God Bless The Master 3:05 2 Dido Bendigo 2:53 3 The Welcome Sailor 3:12 4 Emmanuel 2:48 5 Idumea 1:48 6 The Still And Silent Ocean 4:25 7 Fathom The Bowl 2:52 8 Fare Thee Well Cold Winter 2:32 9 The Holmfirth Anthem 1:58 10 Stormy Winds 3:10 11 Rosebuds In June 3:15 12 Bellman 3:55 13 Sleep On Beloved 3:03 14 Swansea Town 4:18 15 The Beggar Man 3:26 16 Amazing Grace 4:38 17 The Old Churchyard 3:23 18 Adieu Sweet Lovely Nancy 3:38 19 Malpas Wassail 4:11 Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Topic Records Ltd. Copyright (c) – Topic Records Ltd. Licensed From – Topic Records Ltd. Published By – Concorde International Management Consultants Ltd. Published By – Gwyneth Music Ltd. Published By – Topic Records Ltd. Published By – MCS Music Limited Published By – Free Reed Music Published By – April Music Ltd. Published By – Mole Music Ltd Credits Accompanied By – Gabriel's Horns (tracks: 4) Concertina [Anglo-concertina] – Tony Engle (tracks: 15) Fiddle – Peta Webb (tracks: 15) Guitar – Martin Carthy Melodeon – Rod Stradling (tracks: 15) Performer – Anthea Bellamy (tracks: 16), Barry Coope (tracks: 18), Blue Murder (tracks: 18), Eliza Carthy (tracks: 13, 17, 18), Jim Boyes (tracks: 18), Jim -

Sarah Morgan

Context statement – Sarah Morgan Community Choirs – A Musical Transformation A review of my work in management, music, choir leadership and folk-song. The University of Winchester Faculty of Arts Submitted by Sarah Morgan to the University of Winchester The context statement for the degree of Professional Doctorate by Contribution to Public Work This context statement has been completed as a requirement for a Post-Graduate Research Degree of the University of Winchester. The word count in this document is 39, 933. This context statement is available for library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from this statement may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this context statement which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. In accordance with the customs and norms of the host institution, it has not been possible in this work to anonymise organisations. 1 Context statement – Sarah Morgan University of Winchester Abstract for context statement: Community Choirs – A Musical Transformation A review of my work in management, music, choir leadership and folk-song. Sarah Margaret Morgan Faculty of Arts Professional Doctorate by Contribution to Public Work Submission date September 2013 2 Context statement – Sarah Morgan Abstract: My aims have always been to present an exploration of English community choirs, their music and their leadership from a very personal perspective, which brings together my background as a folk musician, my career in training and facilitation, and my developing understanding of a system of musical hierarchies which (though often unspoken) inform and colour not only my own musical experience but that of many others. -

Eliza Carthy & Norma Waterson 03

ELIZA CARTHY & NORMA WATERSON 02 GIFT Eliza Carthy & Norma Waterson TSDL579 www.topicrecords.co.uk ELIZA CARTHY & NORMA WATERSON 03 GIFT Poor Wayfaring Stranger Boston Burglar Bonaparte’s Lament trad. arr Aidan Curran / trad. arr Norma Waterson / trad. arr Eliza Carthy / Norma Waterson Eliza Carthy / Norma Waterson Martin Carthy From the EFDSS Appalachian compilation Dear Companion. Comes from a number of places, mostly out of Mam’s head and Boston Burglar comes from two sources: Delia Murphy and originally, of course, mostly from America. The great Almeida Dominic Behan. Mam has some great stories about Dominic, but The Rose and the Lily Riddle, who when Mam along with the other Watersons met her she isn’t sharing out of respect to everyone involved...recently (the Cruel Brother) at the American Bi-Centennial celebrations in Washington in the gift of a CD of Delia Murphy from Bob Davenport brought the song trad. arr Eliza Carthy / 1976 insisted everyone call her “granny”, was a great performer memories of the whole thing flooding back. She was loved by Norma Waterson / Oliver Knight, and they all got along like a house on fire. She made them a Mam’s Grandma who loved ‘The Spinning Wheel’, the closest thing melody Eliza Carthy present of her album and her book, and sadly is no longer with you got to a “hit” in the fifties. The Dominic Behan connection The idea is that the two siblings represent the two flowers us. Ask Mam how she would sing with her hands one day - it’s comes from being on tour with the Watersons in the sixties, it was of the family: both beautiful, one deadly. -

Bulletin Magazine of the Richard III Society

Ricardian Bulletin Magazine of the Richard III Society ISSN 0308 4337 June 2011 Ricardian June 2011 Bulletin Contents 2 From the Chairman 3 Society News and Notices 7 Introducing our new Business Manager 9 The Ricardian Chronicle 11 Bosworth in 2011 13 Study weekend at York on the de la Pole family, by David and Wendy Johnson 16 Celebrating Paul Murray Kendall 22 News and Reviews (conference on the second battle of St Albans; Blood and Roses weekend at Oxford; Tower of London seminar on Society at War in the 15th century; Fatal Colours and Blood Red Roses at the Mansion House, York; Richard III by The Propeller Company) 34 Crazy Christmas Query, by Phil Stone 35 Sometimes two wrongs do make a right, by Heather Falvey 36 Richard III and Anna Dixie, by John Saunders 38 Media Retrospective 40 The Man Himself: Some ‗Servants and Lovers‘ of Richard III in his youth, by Charles Ross 42 Apple Juice fit for a Duchess, by Tig Lang 43 Papers from the York Study Weekend The Chaucer network of cousins, by Lesley Boatwright (p.44) Chaucer and de la Pole heraldry, by Peter Hammond (p.48) 51 Correspondence 53 The Barton Library 55 From the Visits Team 59 Branches and Groups 62 New Members and Recently Deceased Members 63 Obituaries 64 Calendar Contributions Contributions are welcomed from all members. All contributions should be sent to Lesley Boatwright. Bulletin Press Dates 15 January for March issue; 15 April for June issue; 15 July for September issue; 15 October for December issue. Articles should be sent well in advance. -

Cover Lover the Magazine for First Day and Commemorative Cover Collectors ENGLAND WIN the CRICKET WORLD CUP

AUGUST 2019 CL226 Cover Lover The magazine for first day and commemorative cover collectors ENGLAND WIN THE CRICKET WORLD CUP FULL DETAILS ON PAGE 3 > MOON LANDING 50th ANNIVERSARY SPECIAL SEE PAGE 64 INSIDE THIS ISSUE: MEGHAN & HARRY - ROYAL BABY CHRISTENING • THE LATEST NEW ISSUES • FANTASTIC SIGNERS • D-DAY • SPACE • SPECIALIST FDCS • FLIGHT, RAIL & MARITIME COMMEMORATIVES & MUCH, MUCH MORE! Buckingham Covers - The First in First Day Covers A WORD FROM “The fantastic Cricket result BRIAN meant an interesting Monday BUCKINGHAM COVERS, SPECIALIST COVER EXPERT at Warren House” Dear Collector, All this excitement does not mean we have forgotten about our Forests cover, which is on page 5. I was trying to help on the So, last Sunday I sat down on the sofa, for a ‘top’ sporting telephone this morning and I took three calls in a row all ordering afternoon. It was the Wimbledon Men’s final, but tennis is not it, which certainly makes us feel good. really my thing, I could have watched the F1 British Grand Prix, but over the last few years have lost interest. If I had asked Craig I think last month I mentioned we were trying to get 200 Rail Club and Jake they would have insisted I should have watched the members, which we did a couple of weeks ago, so congratulations Cricket final, but it was a sunny July afternoon, so of course I to Mr D, Mr D and Mr E who all received a free railway album. spent 3½ hours watching an extremely long, dull stage of the Tour Our next target and free albums giveaway is at 225! De France, so did I miss anything? At this point, while I am talking about clubs, I need to mention The fantastic Cricket result meant an interesting Monday at that the club we have referred to variously as the main, standard Warren House and, as I write, all we are really sure of is that or stamps club, will now be known as the Classic Club, which we there will be two miniature sheets, Women’s and Men’s, with think much more fitting. -

Copper Family Recordings: a Complete Discography

Copper Family Recordings: A Complete Discography Singer(s) Title Date Label Includes Notes James and Bob Copper BBC archive 1/3/51 BBC Archive 16060 Adieu Sweet Lovely Not commercially recording by Nancy; Claudy Banks available Peter Kennedy, [+ others?] Rottingdean, Sussex James and Bob Copper BBC archive 1/3/51 BBC Archive 16061 Two Young Brethren Not commercially recording by (?2 versions) [+ available Peter Kennedy, others?] Rottingdean, Sussex James and Bob Copper BBC archive 1/3/51 BBC Archive 16062 Charming Molly; Not commercially recording by When Spring Comes available Peter Kennedy, On; Brisk And Bonny Rottingdean, Sussex Lad [+ others?] James and Bob Copper BBC archive 1/3/51 BBC Archive 16063 Sweep Chimney Not commercially recording by Sweep; No John available Peter Kennedy, No; Brisk Young Rottingdean, Sussex Ploughboy (?) [+ others?] James and Bob Copper BBC archive 1/3/51 BBC Archive 16064 Brisk Young Not commercially recording by Ploughboy (?) [+ available Peter Kennedy, others?] Rottingdean, Sussex James and Bob Copper BBC archive 1/3/51 BBC Archive 16065 The Ploughshare; Not commercially recording by Come Write Me Down available Peter Kennedy, [+ others?] Rottingdean, Sussex James and Bob Copper BBC archive 1/3/51 BBC Archive 16066 Spencer the Rover; Not commercially recording by Shepherd Of The available Peter Kennedy, Downs [+ others?] Rottingdean, Sussex James and Bob Copper BBC archive 1/3/51 BBC Archive 16067 Pleasant Month of Not commercially recording by May; Babes In The available Peter Kennedy, Wood [+ others?] Rottingdean, Sussex Note: six songs from the above 1951 recordings of James Copper were subsequently released commercially on Twankydillo. -

This Is... Martin Carthy: the Bonny Black Hare and Other Songs Mp3, Flac, Wma

Martin Carthy This Is... Martin Carthy: The Bonny Black Hare And Other Songs mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Folk, World, & Country Album: This Is... Martin Carthy: The Bonny Black Hare And Other Songs Country: UK Released: 1971 Style: Folk MP3 version RAR size: 1638 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1192 mb WMA version RAR size: 1906 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 294 Other Formats: MP2 MIDI MPC VOC AAC MOD MPC Tracklist Hide Credits A1 The Fowler 3:15 A2 Brigg Fair 1:32 A3 The Barley Straw 2:32 A4 Byker Hill 2:54 A5 John Barleycorn 3:13 A6 The Bonny Black Hare 2:00 B1 Ship In Distress 2:28 Jack Orion B2 4:03 Adapted By – Lloyd* B3 White Hare 2:47 Lord Of The Dance B4 2:40 Written-By – Carter* B5 Poor Murdered Woman 2:48 B6 Streets Of Forbes 3:20 Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Philips Records Ltd. Published By – Sparta Florida Music Group Ltd. Lacquer Cut At – Phonodisc Ltd. Credits Accompanied By [With] – Dave Swarbrick Arranged By – Martin Carthy Written-By – Traditional Notes ℗ 1968 Side A is six tracks taken from the album Byker Hill. Side B is six tracks taken from the album But Two Came By.... All tracks pub. Sparta-Florida Music Group Ltd. except B4 Barcode and Other Identifiers Matrix / Runout (Side A Label): 6382 022 1 Matrix / Runout (Side B Label): 6382 022 2 Matrix / Runout (Side A runout stamped): 6382022 1Y//1▽420 1 1 5 04 Matrix / Runout (Side B runout stamped): 6382022 2Y//1▽420 1 1 3 04 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Martin This Is..