Sound Recording in the British Folk Revival: Ideology, Discourse and Practice, 1950–1975

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rosemary Lane the Pentangle Magazine

Rosemary Lane the pentangle magazine Issue No 12 Summer 1997 Rosemary Lane Editorial... (thanks, but which season? and we'd Seasonal Greetings! rather have had the mag earlier!) o as the summer turns into autumn here we extensive are these re-issues of the Transatlantic are once more with the latest on Pentangle years - with over 30 tracks on each double CD in Rosemary Lane. In what now seems to be that the juxtaposition of the various musical its characteristic mode of production - i.e. long styles is frequently quite startling and often overdue and much anticipated - thanks for the refreshing in reminding you just how broad the reminders! - we nevertheless have some tasty Pentangle repertoire was in both its collective morsels of Pentangular news and music despite and individual manifestations. More on these the fact that all three current recording projects by in news and reviews. Bert and John and Jacqui remain works in progress - (see, Rosemary Lane is not the only venture that runs foul of the limitations of one human being!). there’s a piece this time round from a young Nonetheless Bert has in fact recorded around 15 admirer of Bert’s who tells how he sounds to the or 16 tracks from which to choose material and in ears of a teenage fan of the likes of Morrissey and the interview on page 11 - Been On The Road So Pulp. And while many may be busy re-cycling Long! - he gives a few clues as to what the tracks Pentangle recordings, Peter Noad writes on how are and some intriguing comments on the feel of Jacqui and band have been throwing themselves the album. -

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

Johnny O'neal

OCTOBER 2017—ISSUE 186 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM BOBDOROUGH from bebop to schoolhouse VOCALS ISSUE JOHNNY JEN RUTH BETTY O’NEAL SHYU PRICE ROCHÉ Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East OCTOBER 2017—ISSUE 186 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 NEw York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : JOHNNY O’NEAL 6 by alex henderson [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : JEN SHYU 7 by suzanne lorge General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The Cover : BOB DOROUGH 8 by marilyn lester Advertising: [email protected] Encore : ruth price by andy vélez Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest We Forget : betty rochÉ 10 by ori dagan [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : southport by alex henderson US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or VOXNEwS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] obituaries Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Fred Bouchard, Festival Report Stuart Broomer, Robert Bush, 13 Thomas Conrad, Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, special feature 14 by andrey henkin Anders Griffen, Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Marilyn Lester, CD ReviewS 16 Suzanne Lorge, Mark Keresman, Marc Medwin, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, Miscellany 41 John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Scott Yanow Event Calendar Contributing Writers 42 Brian Charette, Ori Dagan, George Kanzler, Jim Motavalli “Think before you speak.” It’s something we teach to our children early on, a most basic lesson for living in a society. -

WDAM Radio's History of Peter & Gordon

WDAM Radio's Hit Singles History Of Peter & Gordon # Artist Title Chart Position/Year Comments 01 Peter & Gordon “A World Without Love” #1-U.S. + #1-U.K., Paul McCartney – composer. Credited to John Canada, Ireland, New Lennon & Paul McCartney. Zealand & #2-Australia & #8 in Norway/1964 01A Bobby Rydell “A World Without Love” #80/1964 (#1-Philadelphia Debuted 5/9/1964 – the same date as Peter & & #10 in Chicago) + #5- Gordon’s version. Singapore & #9-Hong Kong. 01B Supremes “A World Without Love” #7-Maylasia/1964 02 Peter & Gordon “Nobody I Know” #12-U.S. + #10-U.K./1964 John Lennon & Paul McCartney – composers. 03 Peter & Gordon “I Don’t Want To See You Again” #16/1964 John Lennon & Paul McCartney – composers. 04 Peter & Gordon “I Go To Pieces” #9-U.S. + #21-Canada, Del Shannon – composer. A-side. #11-Sweden & #26- Australia/1964 04 Lloyd Brown “I Go To Pieces” –/1965 Del Shannon – composer, producer, and second voice harmony. 04B Del Shannon “I Go To Pieces" –/1965 . 05 Peter & Gordon “Love Me Baby” #26-Australia/1964 B-side. 06 Peter & Gordon “True Love Ways” #14-U.S. + #32-U.K./1965 Buddy Holly & Norman Petty – composers, 06A Buddy Holly (& The “True Love Ways” #25-U.K./1960 & #65- Dick Jacobs U.K./1988 Orchestra) 07 Peter & Gordon “To Know You Is To Love You” #24-U.S. + #5-U.K./1965 Phil Spector – composer. 07A Teddy Bears “To Know Him Is To Love Him” #1-U.S. + #2-U.K./1958 & #66-U.K./1979 08 Peter & Gordon “Baby I’m Yours” #19-U.K./1965 08A Barbara Lewis “Baby I’m Yours” #11-Rock & #5-R&B-U.S. -

Fab Four Virtuelles Instrument

Fab Four Virtuelles Instrument Benutzerhandbuch i FAB FOUR VIRTUELLES INSTRUMENT Die Informationen in diesem Dokument können sich jederzeit ohne Ankündigung ändern und stellen keine Verbindlichkeit seitens East West Sounds, Inc. dar. Die Software und die Klänge, auf das sich dieses Dokument bezieht, sind Gegenstand des Lizenzabkommens und dürfen nicht auf andere Medien kopiert werden. Kein Teil dieser Publikation darf kopiert oder reproduziert werden oder auf eine andere Art und Weise übertragen oder aufgenommen werden, egal für welchen Zweck, ohne vorherige schriftliche Erlaubnis von East West Sounds, Inc. Alle Produkt- und Firmennamen sind TM oder ® Warenzeichen seiner jeweiligen Eigentümer. PLAY™ ist ein Markenzeichen von East West Sounds, Inc. © East West Sounds, Inc. 2010. Alle Rechte vorbehalten. East West Sounds, Inc. 6000 Sunset Blvd. Hollywood, CA 90028 USA Telefon: 1-323-957-6969 Fax: 1-323-957-6966 Bei Fragen zur Lizensierung der Produkte: [email protected] Bei allgemeinen Fragen zu den Produkten: [email protected] http://support.soundsonline.com Version von Juli 2010 ii FAB FOUR VIRTUELLES INSTRUMENT 1. Willkommen 2 Produzent: Doug Rogers 4 Tontechniker: Ken Scott 6 Danksagung 8 Wie man dieses und andere Handbücher benutzt 9 Online Dokumentation und andere Hilfsquellen Klicken Sie hier, um das Haupt- navigationsdokument zu öffnen 1 FAB FOUR VIRTUELLES INSTRUMENT Willkommen Produzent: Doug Rogers Doug Rogers hat in der Musikbranche mehr als 30 Jahre Erfahrung und ist der Empfänger von vielen Auszeichnungen inklusive dem „Toningenieur des Jahres“. Im Jahre 2005 nannte „The Art of Digital Music“ ihn einen der „56 Visionary Artists & Insiders“ im gleichnamigen Buch. Im Jahre 1988 gründete er EastWest, den von der Kritik am meisten gefeierten Klangentwickler der Welt. -

Dec. 22, 2015 Snd. Tech. Album Arch

SOUND TECHNIQUES RECORDING ARCHIVE (Albums recorded and mixed complete as well as partial mixes and overdubs where noted) Affinity-Affinity S=Trident Studio SOHO, London. (TRACKED AND MIXED: SOUND TECHNIQUES A-RANGE) R=1970 (Vertigo) E=Frank Owen, Robin Geoffrey Cable P=John Anthony SOURCE=Ken Scott, Discogs, Original Album Liner Notes Albion Country Band-Battle of The Field S=Sound Techniques Studio Chelsea, London. (TRACKED AND MIXED: SOUND TECHNIQUES A-RANGE) S=Island Studio, St. Peter’s Square, London (PARTIAL TRACKING) R=1973 (Carthage) E=John Wood P=John Wood SOURCE: Original Album liner notes/Discogs Albion Dance Band-The Prospect Before Us S=Sound Techniques Studio Chelsea, London. (PARTIALLY TRACKED. MIXED: SOUND TECHNIQUES A-RANGE) S=Olympic Studio #1 Studio, Barnes, London (PARTIAL TRACKING) R=Mar.1976 Rel. (Harvest) @ Sound Techniques, Olympic: Tracks 2,5,8,9 and 14 E= Victor Gamm !1 SOUND TECHNIQUES RECORDING ARCHIVE (Albums recorded and mixed complete as well as partial mixes and overdubs where noted) P=Ashley Hutchings and Simon Nicol SOURCE: Original Album liner notes/Discogs Alice Cooper-Muscle of Love S=Sunset Sound Recorders Hollywood, CA. Studio #2. (TRACKED: SOUND TECHNIQUES A-RANGE) S=Record Plant, NYC, A&R Studio NY (OVERDUBS AND MIX) R=1973 (Warner Bros) E=Jack Douglas P=Jack Douglas and Jack Richardson SOURCE: Original Album liner notes, Discogs Alquin-The Mountain Queen S= De Lane Lea Studio Wembley, London (TRACKED AND MIXED: SOUND TECHNIQUES A-RANGE) R= 1973 (Polydor) E= Dick Plant P= Derek Lawrence SOURCE: Original Album Liner Notes, Discogs Al Stewart-Zero She Flies S=Sound Techniques Studio Chelsea, London. -

Off the Beaten Track

Off the Beaten Track To have your recording considered for review in Sing Out!, please submit two copies (one for one of our reviewers and one for in- house editorial work, song selection for the magazine and eventual inclusion in the Sing Out! Resource Center). All recordings received are included in “Publication Noted” (which follows “Off the Beaten Track”). Send two copies of your recording, and the appropriate background material, to Sing Out!, P.O. Box 5460 (for shipping: 512 E. Fourth St.), Bethlehem, PA 18015, Attention “Off The Beaten Track.” Sincere thanks to this issue’s panel of musical experts: Richard Dorsett, Tom Druckenmiller, Mark Greenberg, Victor K. Heyman, Stephanie P. Ledgin, John Lupton, Angela Page, Mike Regenstreif, Seth Rogovoy, Ken Roseman, Peter Spencer, Michael Tearson, Theodoros Toskos, Rich Warren, Matt Watroba, Rob Weir and Sule Greg Wilson. that led to a career traveling across coun- the two keyboard instruments. How I try as “The Singing Troubadour.” He per- would have loved to hear some of the more formed in a variety of settings with a rep- unusual groupings of instruments as pic- ertoire that ranged from opera to traditional tured in the notes. The sound of saxo- songs. He also began an investigation of phones, trumpets, violins and cellos must the music of various utopian societies in have been glorious! The singing is strong America. and sincere with nary a hint of sophistica- With his investigation of the music of tion, as of course it should be, as the Shak- VARIOUS the Shakers he found a sect which both ers were hardly ostentatious. -

Charles Parker, Documentary Performance, and the Search for a Popular Culture

David Watt ‘The Maker and the Tool’: Charles Parker, Documentary Performance, and the Search for a Popular Culture Charles Parker’s BBC Radio Ballads of the late 1950s and early 1960s, acknowledged by Derek Paget in NTQ 12 (November 1987) as a formative influence on the emergence of what he called ‘Verbatim Theatre’, have been given a new lease of life following their recent release by Topic Records; but his theatrical experiments in multi-media documentary, which he envisaged as a model for ‘engendering direct creativity in the common people’, remain largely unknown. The most ambitious of these – The Maker and the Tool, staged as part of the Centre 42 festivals of 1961–62 – is exemplary of the impulse to recreate a popular culture which preoccupied many of those involved in the Centre 42 venture. David Watt, who teaches Drama at the University of Newcastle, New South Wales, began researching these experiments with work on a case study of Banner Theatre of Actuality, the company Parker co-founded in 1973, for Workers’ Playtime: Theatre and the Labour Movement since 1970, co-authored with Alan Filewod. This led to further research in the Charles Parker Archive at Birmingham Central Library, and the author is grateful to the Charles Parker Archive Trust and the staff of the Birmingham City Archives (particularly Fiona Tait) for the opportunity to explore its holdings and draw on them for this article. IN JANUARY 1963 an amateur theatre group The Maker and the Tool, a ‘Theatre Folk Ballad’ in Birmingham, the Leaveners, held its first written/compiled and directed by Charles annual general meeting and moved accep- Parker and staged in a range of non-theatre tance of the following statement of aims: spaces in six different versions, one for each of the festival towns. -

Informal Popular Music Learning Practice and Their Relevance for Formal Music Educators

17 INFORMAL POPULAR MUSIC LEARNING PRACTICE AND THEIR RELEVANCE FOR FORMAL MUSIC EDUCATORS Lucy Green Institute of Education, University of London Introduction I would like to start by listening to the opening of a song. It is performed by Nanette Welmans, an English popular musician who I interviewed as part of a study on how popular musicians learn. Nanette does all the singing on the recording, including the backing vocals; she plays all the instruments and she mixed the recording herself. She also composed the music and wrote the lyrics. Like the majority of popular musicians, she had hardly any formal music education at all. She had taken a few piano lessons when she was ten years old, but gave up because in her words: ‘I just couldn’t relate to them, at all’. She became a professional singer at the age of 17, but only went to a singing teacher later. She had two separate periods of taking lessons, mainly concentrating on diaphragm breathing. At the time of creating this song, she did not know how to read notation; and it emerged after the interview that she had notation dyslexia. She had never had any education in composition, form, harmony or counterpoint. There are three main questions I wish to address in this presentation. Firstly, how did she, and other musicians like her, go about the informal processes of acquiring their skills and knowledge; secondly, what kinds of attitudes and values did they bring to their learning experiences; thirdly, and more briefly, to what extent might it be beneficial to incorporate these learning practices into the formal environment of the general school music classroom? The research involved detailed interviews and some observations with 14 popular musicians living in and around London, UK, aged 15 to 50. -

“What Happened to the Post-War Dream?”: Nostalgia, Trauma, and Affect in British Rock of the 1960S and 1970S by Kathryn B. C

“What Happened to the Post-War Dream?”: Nostalgia, Trauma, and Affect in British Rock of the 1960s and 1970s by Kathryn B. Cox A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music Musicology: History) in the University of Michigan 2018 Doctoral Committee: Professor Charles Hiroshi Garrett, Chair Professor James M. Borders Professor Walter T. Everett Professor Jane Fair Fulcher Associate Professor Kali A. K. Israel Kathryn B. Cox [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-6359-1835 © Kathryn B. Cox 2018 DEDICATION For Charles and Bené S. Cox, whose unwavering faith in me has always shone through, even in the hardest times. The world is a better place because you both are in it. And for Laura Ingram Ellis: as much as I wanted this dissertation to spring forth from my head fully formed, like Athena from Zeus’s forehead, it did not happen that way. It happened one sentence at a time, some more excruciatingly wrought than others, and you were there for every single sentence. So these sentences I have written especially for you, Laura, with my deepest and most profound gratitude. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Although it sometimes felt like a solitary process, I wrote this dissertation with the help and support of several different people, all of whom I deeply appreciate. First and foremost on this list is Prof. Charles Hiroshi Garrett, whom I learned so much from and whose patience and wisdom helped shape this project. I am very grateful to committee members Prof. James Borders, Prof. Walter Everett, Prof. -

CY 2001 Compared to CY 2000

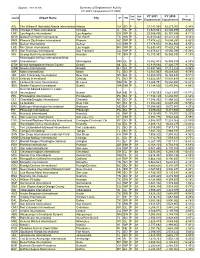

Source: 2001 ACAIS Summary of Enplanement Activity CY 2001 Compared to CY 2000 Svc Hub CY 2001 CY 2000 % Locid Airport Name City ST RO Lvl Type Enplanement Enplanement Change ATL The William B Hartsfield Atlanta International Atlanta GA SO P L 37,181,068 39,277,901 -5.34% ORD Chicago O'Hare International Chicago IL GL P L 31,529,561 33,845,895 -6.84% LAX Los Angeles International Los Angeles CA WP P L 29,365,436 32,167,896 -8.71% DFW Dallas/Fort Worth International Fort Worth TX SW P L 25,610,562 28,274,512 -9.42% PHX Phoenix Sky Harbor International Phoenix AZ WP P L 17,478,622 18,094,251 -3.40% DEN Denver International Denver CO NM P L 17,178,872 18,382,940 -6.55% LAS Mc Carran International Las Vegas NV WP P L 16,633,435 17,425,214 -4.54% SFO San Francisco International San Francisco CA WP P L 16,475,611 19,556,795 -15.76% IAH George Bush Intercontinental Houston TX SW P L 16,173,551 16,358,035 -1.13% Minneapolis-St Paul International/Wold- MSP Chamberlain/ Minneapolis MN GL P L 15,852,433 16,959,014 -6.53% DTW Detroit Metropolitan Wayne County Detroit MI GL P L 15,819,584 17,326,775 -8.70% EWR Newark International Newark NJ EA P L 15,497,560 17,212,226 -9.96% MIA Miami International Miami FL SO P L 14,941,663 16,489,341 -9.39% JFK John F Kennedy International New York NY EA P L 14,553,815 16,155,437 -9.91% MCO Orlando International Orlando FL SO P L 13,622,397 14,831,648 -8.15% STL Lambert-St Louis International St. -

The Merry Mawkin the Friends of Norfolk Dialect Newsletter

THE MERRY MAWKIN THE FRIENDS OF NORFOLK DIALECT NEWSLETTER Number 61 Summer 2016 £1.50 www.norfolkdialect.com SUMMER 2016 THE MERRY MAWKIN 1 Chairman’s report t’s here! Welcome to the Isummer edition of The Merry Mawkin. You may notice it looks a little bit different, but it’s still as full of news, memories and squit as ever. We’ve had a few changes behind the scenes Front cover: Rhodedendrons since the last Merry Mawkin was published. at Sheringham Park. Ashley Gray, who has done a wonderful job Back cover: Swan family at designing and editing The Merry Mawkin for Glandford. nine years has decided to step down from this role and also his role of webmaster. My grateful thanks go to him for the many hours IN THIS ISSUE of hard work he put in to help FOND and for 2 Chairman’s report creating the professional look of the magazine 4 FOND officers & committee and website. 4 Membership application form 5 The Smella Wet Sand I’m sure you, as members of FOND, will 6 My Grandad echo me in saying that he really did produce 8 Spring has sprung something to be proud of. Ashley designed 9 NDF 2016 10 Ha you bin leartly? and edited a grand total of 34 Merry Mawkins. 11 Dialect Talks They made a great picture when I laid each one 12 Gorn on holidy? out to take a photograph of them to present to 12 Colin Boy’s Quiz him. I did have to add one to make the picture 13 The Cromer Dew look complete — can you spot it? Without 16 The Bridge at Lyng 17 Wordsearch even realising I doubled up on Wymondham 18 Tales from the Back Loke Abbey; most appropriate with Ashley being a 20 Fewd, Glorious fewd Wymondham boy! Ashley was also presented 21 Trosher Competition with life membership of FOND, some Norfolk 21 Membership 21 Wordsearch answers punch and a fond memories clematis.