Informal Popular Music Learning Practice and Their Relevance for Formal Music Educators

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rosemary Lane the Pentangle Magazine

Rosemary Lane the pentangle magazine Issue No 12 Summer 1997 Rosemary Lane Editorial... (thanks, but which season? and we'd Seasonal Greetings! rather have had the mag earlier!) o as the summer turns into autumn here we extensive are these re-issues of the Transatlantic are once more with the latest on Pentangle years - with over 30 tracks on each double CD in Rosemary Lane. In what now seems to be that the juxtaposition of the various musical its characteristic mode of production - i.e. long styles is frequently quite startling and often overdue and much anticipated - thanks for the refreshing in reminding you just how broad the reminders! - we nevertheless have some tasty Pentangle repertoire was in both its collective morsels of Pentangular news and music despite and individual manifestations. More on these the fact that all three current recording projects by in news and reviews. Bert and John and Jacqui remain works in progress - (see, Rosemary Lane is not the only venture that runs foul of the limitations of one human being!). there’s a piece this time round from a young Nonetheless Bert has in fact recorded around 15 admirer of Bert’s who tells how he sounds to the or 16 tracks from which to choose material and in ears of a teenage fan of the likes of Morrissey and the interview on page 11 - Been On The Road So Pulp. And while many may be busy re-cycling Long! - he gives a few clues as to what the tracks Pentangle recordings, Peter Noad writes on how are and some intriguing comments on the feel of Jacqui and band have been throwing themselves the album. -

Sound Recording in the British Folk Revival: Ideology, Discourse and Practice, 1950–1975

Sound recording in the British folk revival: ideology, discourse and practice, 1950–1975 Matthew Ord Submitted in fulfilment of the degree of PhD International Centre for Music Studies Newcastle University March 2017 Abstract Although recent work in record production studies has advanced scholarly understandings of the contribution of sound recording to musical and social meaning, folk revival scholarship in Britain has yet to benefit from these insights. The revival’s recording practice took in a range of approaches and contexts including radio documentary, commercial studio productions and amateur field recordings. This thesis considers how these practices were mediated by revivalist beliefs and values, how recording was represented in revivalist discourse, and how its semiotic resources were incorporated into multimodal discourses about music, technology and traditional culture. Chapters 1 and 2 consider the role of recording in revivalist constructions of traditional culture and working class communities, contrasting the documentary realism of Topic’s single-mic field recordings with the consciously avant-garde style of the BBC’s Radio Ballads. The remaining three chapters explore how the sound of recorded folk was shaped by a mutually constitutive dialogue with popular music, with recordings constructing traditional performance as an authentic social practice in opposition to an Americanised studio sound equated with commercial/technological mediation. As the discourse of progressive rock elevated recording to an art practice associated with the global counterculture, however, opportunities arose for the incorporation of rock studio techniques in the interpretation of traditional song in the hybrid genre of folk-rock. Changes in studio practice and technical experiments with the semiotics of recorded sound experiments form the subject of the final two chapters. -

Sponsorship Opportunities Killebrew

KILLEBREW-THOMPSON MEMORIAL SPONSORSHIP OPPORTUNITIES August 19-22, 2020 | Sun Valley, Idaho A Leukemia & Cancer Research Benefit ©Jordyn Dooley Dear Friend of KTM, We are pleased to invite you to the 44th Annual Killebrew-Thompson Memorial, August 19-22, 2020 at beautiful Sun Valley Resort. Thanks to the generosity of our 2019 supporters, $800,000 was donated to our beneficiaries to fund cutting-edge cancer research and patient care. The resulting innovations in cancer treatments and therapies are improving outcomes for an untold number of cancer patients and their families. Hannah Stauts We hope you will join us, as a sponsor or participant, for a fun-filled weekend Executive Director enjoying all that Idaho has to offer. With your support, we will be one step closer to a cancer-free tomorrow. Board of Directors Marc Butler, Chairman Evan Robertson, Secretary Georgie Fenton Mark Johnson Doug Oppenheimer CEO, JR Butler, Inc. Robertson & Slette, PLLC (Former) President, KTM News Anchor, KTVB/NBC President, Oppenheimer Denver, CO Twin Falls, ID Sun Valley, ID Boise, ID Companies Boise, ID Joe Puishys, Vice Chairman Terrance Dolan Russell Huffer Ross Matthews CEO, Apogee Enterprises Vice Chairman, US Bank CEO (Retired), Apogee Enterprises President, Sinclair Oil Minneapolis, MN Minneapolis, MN Eden Prairie, MN Salt Lake City, UT Paul Hartzell, Treasurer John Elmore John D. Jackson Marvin May Founder/Partner, Verichain Partners Vice Chairman (Retired), US Bank CEO, Jackson Food Stores Owner, May Trucking Company Hailey, ID Minneapolis, MN Boise, ID Salem, OR ABOUT US History The Killebrew-Thompson Memorial is dedicated to raising funds for Danny Thompson played shortstop for the Minnesota leukemia and cancer research through an annual charity event held in Twins for only one season before being diagnosed with Sun Valley, Idaho. -

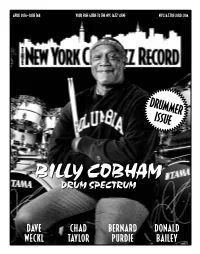

Drummerissue

APRIL 2016—ISSUE 168 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM drumMER issue BILLYBILLY COBHAMCOBHAM DRUMDRUM SPECTRUMSPECTRUM DAVE CHAD BERNARD DONALD WECKL TAYLOR PURDIE BAILEY Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East APRIL 2016—ISSUE 168 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 New York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : Dave Weckl 6 by ken micallef [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : Chad Taylor 7 by ken waxman General Inquiries: [email protected] On The Cover : Billy Cobham 8 by john pietaro Advertising: [email protected] Encore : Bernard Purdie by russ musto Editorial: 10 [email protected] Calendar: Lest We Forget : Donald Bailey 10 by donald elfman [email protected] VOXNews: LAbel Spotlight : Amulet by mark keresman [email protected] 11 Letters to the Editor: [email protected] VOXNEWS 11 by suzanne lorge US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 In Memoriam 12 by andrey henkin International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or money order to the address above FESTIVAL REPORT or email [email protected] 13 Staff Writers CD Reviews 14 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Fred Bouchard, Stuart Broomer, Thomas Conrad, Miscellany 36 Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Philip Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Event Calendar Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, 38 Alex Henderson, Marcia Hillman, Terrell Holmes, Robert Iannapollo, Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Ken Micallef, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, As we head into spring, there is a bounce in our step. -

MADDY PRIOR– EFDSS Gold Badge Testimonial Maddy Prior Is Without Doubt One of the Best Known Voices from the English Folk Revi

MADDY PRIOR– EFDSS Gold Badge Testimonial Maddy Prior is without doubt one of the best known voices from the English folk revival, with a career spanning over forty years which continues today, and several key recordings which will always be identified with her, including by generations born long after the original release of those songs. Her work, however, has extended way beyond her global hits Gaudete and All Around my Hat. Born in Blackpool to Z-Cars co-creator Alan Prior, Maddy grew up in St Albans where she came to prominence in the late 1960’s in a duo with singer/ guitarist Tim Hart, who built a reputation on the folk club circuit, releasing two albums. In the early 1970’s they joined forces with Ashley Hutchings (of Fairport Convention) and Gay & Terry Woods, with the idea of fusing folk song with rock instrumentation and technique. The new group took its name from a traditional Lincolnshire ballad 'Horkstow Grange' - the tale of a character called Steeleye Span. As is well known, Steeleye Span took folk music out of the clubs and into the charts with a string of consistently strong hit albums, gold discs and world tours. Tim Hart and Maddy Prior remained the core of the group whose changing line-ups read like a Who's Who of British folk until Tim left for health reasons in 1980. Maddy continued to work with the band in its changing line-ups until 1997, when after two massive tours around the release of the album Time, she left the band after 28 years, only to return to work with them again from 2002 onwards, and is still touring with them today. -

Minutes of the Meeting of the Assembly Committee on Government Affairs

MINUTES OF THE MEETING OF THE ASSEMBLY COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENT AFFAIRS Eightieth Session June 2, 2019 The Committee on Government Affairs was called to order by Chair Edgar Flores at 3:37 p.m. on Sunday, June 2, 2019, in Room 4100 of the Legislative Building, 401 South Carson Street, Carson City, Nevada. The meeting was videoconferenced to Room 4404B of the Grant Sawyer State Office Building, 555 East Washington Avenue, Las Vegas, Nevada. Copies of the minutes, including the Agenda (Exhibit A), the Attendance Roster (Exhibit B), and other substantive exhibits, are available and on file in the Research Library of the Legislative Counsel Bureau and on the Nevada Legislature's website at www.leg.state.nv.us/App/NELIS/REL/80th2019. COMMITTEE MEMBERS PRESENT: Assemblyman Edgar Flores, Chair Assemblyman William McCurdy II, Vice Chair Assemblyman Alex Assefa Assemblywoman Shannon Bilbray-Axelrod Assemblyman Richard Carrillo Assemblywoman Bea Duran Assemblyman John Ellison Assemblywoman Michelle Gorelow Assemblyman Gregory T. Hafen II Assemblywoman Melissa Hardy Assemblyman Glen Leavitt Assemblywoman Susie Martinez Assemblywoman Connie Munk Assemblyman Greg Smith COMMITTEE MEMBERS ABSENT: None GUEST LEGISLATORS PRESENT: Senator David R. Parks, Senate District No. 7 Senator Moises (Mo) Denis, Senate District No. 2 Minutes ID: 1421 *CM1421* Assembly Committee on Government Affairs June 2, 2019 Page 2 STAFF MEMBERS PRESENT: Jered McDonald, Committee Policy Analyst Asher Killian, Committee Counsel Connie Jo Smith, Committee Secretary Trinity Thom, Committee Assistant OTHERS PRESENT: Michael Brown, Director, Department of Business and Industry Bruce K. Snyder, Commissioner, Local Government Employee-Management Relations Board, Department of Business and Industry Carter Bundy, Political Action Representative, American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, AFL-CIO Richard P. -

![Brevardier [1968]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0403/brevardier-1968-2850403.webp)

Brevardier [1968]

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2018 with funding from North Carolina Digital Heritage Center https://archive.org/details/brevardier196824brev Faithful and true-hearted, Joyous arid ever loyal. Let us boost for our old high. Let us boost for our old high. We revere her and defend her, Let every heart sing. As her colors proudly fly. Let every voice ring; We will stand for her united; There’s no time to grieve or sigh. Of her deeds well proudly tell. It’s ever onward our course pursuing. Her colors streaming. May defeat ne’er our ardor cool, Glad faces beaming. But united we will boost for So here’s a cheer for her. Our Brevard High School. That we all love so well. 1968 BREVARDIER Volume XXIV Brevard High School Brevard, North Carolina By Day, by Night Table of Contents Dedication 4 Introduction 5 Features 16 CLUBS 24 ACADEMICS 48 Administration 50 Faculty 52 SPORTS 76 Football 78 Homecoming Court 84 Cheerleaders 86 J.V. Football 89 Basketball 90 Sports Award 96 Wrestling 97 Track 98 Baseball 100 Golf 101 CLASSES 102 Freshmen 104 Sophomores 110 Juniors 116 Seniors 124 Senior Directory 136 Index 140 2 Determination Overcomes . Mr. Jim Johnson Coach Jim Johnson, a man of skill and determination, is a prominent figure at BHS who has always worked for the betterment of our school. His friendly smile has been seen here for six years. Coach Johnson has been end coach for the football team for several years. He coached the baseball team and has helped to bring the conference champi¬ onship to Brevard. -

On Stage (Extra): a 'Curious' Case of Broadway-Style Entertainment

On Stage (Extra): A ‘Curious’ case of Broadway-style entertainment Feb 25th, 2017 · 0 Comment By Denny Dyroff, Staff Writer, The Times The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time. Theater fans from this area have been very fortunate this month – mainly because of the offerings from the Kimmel Center’s “Broadway Philadelphia” series at the Academy of Music (Broad and Locust streets, Philadelphia, 215-731-3333, www.kimmelcenter.org). Instead of being presented for the umpteenth time with tried-and-true musicals such as “Annie,” “Sound of Music” or “Rent,” fans are being treated to two hit shows that are fresh off Broadway and making their Philadelphia debuts. “The Bodyguard” is running through February 26. Then, from February 28-March 5, the Academy of Music is hosting “The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time.” Hailed as “One of the most fully immersive works ever to wallop Broadway” by The New York Times, this adaptation is the Tony Award®-winning new play by Simon Stephens, adapted from Mark Haddon’s best- selling novel and directed by Tony winner Marianne Elliott. Winner of the 2015 Tony Award for Best New Play, the acclaimed National Theatre production of “The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time” is now on its first North American tour. Two-time Tony Award winner Marianne Elliott (“War Horse”) directs this adaptation by Tony and Olivier Award winner Simon Stephens – an adaptation that brings Mark Haddon’s internationally best-selling novel to thrilling life. Christopher John Francis Boone, a 15-year-old boy with an extraordinary brain, is exceptionally intelligent but ill-equipped to interpret everyday life. -

Of 2 DAWSON COUNTY BOARD of COMMISSIONERS WORK SESSION AGENDA

DAWSON COUNTY BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS WORK SESSION AGENDA – THURSDAY, JANUARY 21, 2021 DAWSON COUNTY GOVERNMENT CENTER ASSEMBLY ROOM 25 JUSTICE WAY, DAWSONVILLE, GEORGIA 30534 4:00 PM UNFINISHED BUSINESS 1. Presentation of Review of Dawson County Employee Handbook's Paid Time Off Policy (Section 14.3) (Tabled from the July 2, 2020, Voting Session)- Human Resources Director Brad Gould NEW BUSINESS 1. Presentation of Request to Accept 2021 Criminal Justice Coordinating Council K9 Grant- Sheriff's Office Chief Deputy Greg Rowan 2. Presentation of Center for Tech and Civic Life COVID-19 Response Grant Funding Approval Request- Chief Registrar / Board of Elections and Registration Chair Glenda Ferguson 3. Presentation of Request to Accept Georgia Child Passenger Safety Mini-Grant- Emergency Services Director Danny Thompson 4. Presentation of IFB #357-19 - Rock Creek Park Berm Construction - Change Order / Funding Request- Public Works Director David McKee / Purchasing Manager Melissa Hawk 5. Presentation of Harry Sosebee Road Right-of-Way and Development Agreement Acceptance- Public Works Director David McKee 6. Presentation of Green Infrastructure and Low Impact Development Program- Public Works Director David McKee 7. Presentation of Elected Official Salaries- Human Resources Director Brad Gould 8. Presentation of an Intergovernmental Agreement with the City of Dawsonville and the Dawson County Board of Elections and Registration Relating to the 2021 Municipal Elections for the City of Dawsonville- County Attorney Angela Davis 9. Presentation of Board Appointments: a. EMS Advisory Council i. Danny Thompson- reappointment (Term: January 2021 through December 2022) ii. Robby Lee- reappointment (Term: January 2021 through December 2022) b. Health Board i. -

Vinyl Catalogue 2014

VINYL CATALOGUE 2014 Established in 2004, Back On Black - together with subsidiary label Back On Black Rock Classics - specialises in vinyl editions of classic metal and rock albums and is dedicated to providing top quality releases for record collectors and rock fans worldwide. Our releases are pressed on exquisite, heavyweight vinyl to produce the very best in sound quality with a mesmerizing tactile feel that makes them a pleasure to handle. Beautiful vinyl colours are carefully chosen to complement the artwork, with some releases available in a variety of colours for the dedicated collector. Many releases are double, or even triple, LPs! The artwork itself is re-worked to faithfully interpret the original album, and reproduced on superior grade gatefold sleeves in heavyweight card with a superb and un-rivalled finish. As well as all our re-mastered LPs of classic albums from throughout history, Back On Black also issues many exclusive vinyl editions of contemporary metal and rock releases. Far from being dead, our beloved vinyl format is going from strength to strength – and Back On Black is proud to serve the needs of the vinyl connoisseur! Just take a look at our catalogue of releases to see the calibre of albums we release! Combine your favourite rock and metal with your favourite format – and get your music Back On Black! CONtact: PHONE: +44 (0)1491 825029 MAILORDER: PLASTICHEAD.COM UK SALES: [email protected] INTERNATIONAL SALES: [email protected] BACKONBLACK.COM facebook.COM/BACKONBLACKRECORDS PLASTICHEAD.COM All titles subject to availability due to territorial or licensing terms. -

77Th February 21, 2013 0100 PM

MINUTES OF THE SENATE COMMITTEE ON REVENUE AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT Seventy-Seventh Session February 21, 2013 The Senate Committee on Revenue and Economic Development was called to order by Chair Ruben J. Kihuen at 1:17 p.m. on Thursday, February 21, 2013, in Room 1214 of the Legislative Building, Carson City, Nevada. The meeting was videoconferenced to Room 4412E of the Grant Sawyer State Office Building, 555 East Washington Avenue, Las Vegas, Nevada. Exhibit A is the Agenda. Exhibit B is the Attendance Roster. All exhibits are available and on file in the Research Library of the Legislative Counsel Bureau. COMMITTEE MEMBERS PRESENT: Senator Ruben J. Kihuen, Chair Senator David R. Parks, Vice Chair Senator Moises (Mo) Denis Senator Debbie Smith Senator Ben Kieckhefer Senator Michael Roberson Senator Greg Brower GUEST LEGISLATORS PRESENT: Senator Kelvin D. Atkinson, Senatorial District No. 4 Senator Aaron D. Ford, Senatorial District No. 11 Senator Justin C. Jones, Senatorial District No. 9 STAFF MEMBERS PRESENT: Russell Guindon, Principal Deputy Fiscal Analyst Joe Reel, Deputy Fiscal Analyst Bryan Fernley-Gonzalez, Counsel Gayle Rankin, Committee Secretary OTHERS PRESENT: James "JR" Reid, JR Lighting, Inc. Joshua Cohen, Cohencidence Productions LLC Brett J. Scolari, Reno-Sparks Convention and Visitors Authority Senate Committee on Revenue and Economic Development February 21, 2013 Page 2 Christopher Baum, CHME, President and CEO, Reno-Sparks Convention and Visitors Authority Jeffrey Spilman, Bottom Line Entertainment LLC Chris Ramirez, Silver State Production Services Randy Soltero, International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees; International Brotherhood of Teamsters; Screen Actors Guild-American Federation of Television and Radio Artists Jerry Dugan, FLF Films, Inc. -

13 February 2009 Page 1 of 12

Radio 4 Listings for 7 – 13 February 2009 Page 1 of 12 SATURDAY 07 FEBRUARY 2009 Correspondent Rob Watson discusses the interest surrounding The latest national and international news from BBC Radio 4. the US administration's first big speech on global security. SAT 00:00 Midnight News (b00h9036) The latest national and international news from BBC Radio 4. Rachel Reid says she had no relationship with the senior British SAT 13:10 Any Questions? (b00h900k) Followed by weather. officer arrested for alleged security leaks. Jonathan Dimbleby chairs the topical debate in Canterbury. The panel includes Ann Widdecombe, John Sergeant, Greg Dyke Iraqi Dr Sana Nimer explains what has changed in the country and Chuka Umunna. SAT 00:30 Book of the Week (b00hd350) over the last two years. The Last Supper Cllr David Sparks discusses how well councils are coping with SAT 14:00 Any Answers? (b00h9dl0) Episode 5 the adverse weather conditions. Jonathan Dimbleby takes listeners' calls and emails in response to this week's edition of Any Questions? Holly Aird reads Rachel Cusk's story of her family's three- Matthew Price examines if George W. Bush will be missed by month tour of Italy, during which they discover some of the comedians. country's rich artistic heritage and enjoy adapting to a more SAT 14:30 Saturday Drama (b00h9dl2) relaxed way of life. Social worker trainer Joanna Nicolas discusses the media On the Ceiling handling of the Baby P case. The family explore Rome's artistic heritage, as their trip draws by Nigel Planer to an end.