Sarah Morgan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Page 1 FLOATING STAGE CONCERTS THURSDAY 9TH

FLOATING STAGE CONCERTS WEDNESDAY 8TH JULY THURSDAY 9TH JULY FRIDAY 10TH JULY Sponsored by Westcoast 20.45 20.45 20.35 22.15 S O P H I E SARA COX MADNESS JAMES BLUNT PRESENTS ELLIS-BEXTOR JUST CAN’T GET ENOUGH 80s Sophie Ellis-Bextor shot to fame as a vocalist on If you’ve got fond memories of legwarmers and Spiller’s huge number one single Groovejet, followed spandex, ‘Just Can’t Get Enough 80s’ is a new show by Take Me Home and her worldwide smash hit, set to send you into a retro frenzy. Murder on the Dancefloor. Join Sara Cox for all the hits from the best decade, Her solo debut album, Read My Lips was released in delivered with a stunning stage set and amazing visuals. 2001 and reached number two in the UK Albums Chart Huge anthems for monumental crowd participation and was certified double platinum by the BPI. moments making epic memories to take home. Her subsequent album releases include Shoot from the Hip (2003), Trip the Light Fantastic (2007) and Make a Scene (2011). In 2014, in a departure from her previous dance pop Madness is a band that retains a strong sense of who and what it is. Ticket prices The five-time Grammy nominated and multiple BRIT award winning Ticket prices Ticket prices albums, Sophie embarked on her debut singer/songwriter Many of the same influences are still present in their sound – ska, Grandstand A £140 artist James Blunt is no stranger to festival spotlight and will the Grandstand A £140 Grandstand A £135 album Wanderlust with Ed Harcourt as co-writer and reggae, Motown, rock’n’roll, rockabilly, classic pop, and the pin-sharp Grandstand B £120 wow crowds at Henley Festival. -

Folk Song in Cumbria: a Distinctive Regional

FOLK SONG IN CUMBRIA: A DISTINCTIVE REGIONAL REPERTOIRE? A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Susan Margaret Allan, MA (Lancaster), BEd (London) University of Lancaster, November 2016 ABSTRACT One of the lacunae of traditional music scholarship in England has been the lack of systematic study of folk song and its performance in discrete geographical areas. This thesis endeavours to address this gap in knowledge for one region through a study of Cumbrian folk song and its performance over the past two hundred years. Although primarily a social history of popular culture, with some elements of ethnography and a little musicology, it is also a participant-observer study from the personal perspective of one who has performed and collected Cumbrian folk songs for some forty years. The principal task has been to research and present the folk songs known to have been published or performed in Cumbria since circa 1900, designated as the Cumbrian Folk Song Corpus: a body of 515 songs from 1010 different sources, including manuscripts, print, recordings and broadcasts. The thesis begins with the history of the best-known Cumbrian folk song, ‘D’Ye Ken John Peel’ from its date of composition around 1830 through to the late twentieth century. From this narrative the main themes of the thesis are drawn out: the problem of defining ‘folk song’, given its eclectic nature; the role of the various collectors, mediators and performers of folk songs over the years, including myself; the range of different contexts in which the songs have been performed, and by whom; the vexed questions of ‘authenticity’ and ‘invented tradition’, and the extent to which this repertoire is a distinctive regional one. -

Kathy Sledge Press

Web Sites Website: www.kathysledge.com Website: http: www.brightersideofday.com Social Media Outlets Facebook: www.facebook.com/pages/Kathy-Sledge/134363149719 Twitter: www.twitter.com/KathySledge Contact Info Theo London, Management Team Email: [email protected] Kathy Sledge is a Renaissance woman — a singer, songwriter, author, producer, manager, and Grammy-nominated music icon whose boundless creativity and passion has garnered praise from critics and a legion of fans from all over the world. Her artistic triumphs encompass chart-topping hits, platinum albums, and successful forays into several genres of popular music. Through her multi-faceted solo career and her legacy as an original vocalist in the group Sister Sledge, which included her lead vocals on worldwide anthems like "We Are Family" and "He's the Greatest Dancer," she's inspired millions of listeners across all generations. Kathy is currently traversing new terrain with her critically acclaimed show The Brighter Side of Day: A Tribute to Billie Holiday plus studio projects that span elements of R&B, rock, and EDM. Indeed, Kathy's reached a fascinating juncture in her journey. That journey began in Philadelphia. The youngest of five daughters born to Edwin and Florez Sledge, Kathy possessed a prodigious musical talent. Her grandmother was an opera singer who taught her harmonies while her father was one-half of Fred & Sledge, the tapping duo who broke racial barriers on Broadway. "I learned the art of music from my father and my grandmother. The business part of music was instilled through my mother," she says. Schooled on an eclectic array of artists like Nancy Wilson and Mongo Santamaría, Kathy and her sisters honed their act around Philadelphia and signed a recording contract with Atco Records. -

Folk for Art's Sake: English Folk Music in the Mainstream Milieu

Volume 4 (2009) ISSN 1751-7788 Folk for Art’s Sake: English Folk Music in the Mainstream Milieu Simon Keegan-Phipps University of Sheffield The English folk arts are currently undergoing a considerable resurgence; 1 practices of folk music, dance and drama that explicitly identify themselves as English are the subjects of increasing public interest throughout England. The past five years have seen a manifold increase in the number of professional musical acts that foreground their Englishness; for the first time since the last 'revival period' of the 1950s and 60s, it is easier for folk music agents to secure bookings for these English acts in England than Scottish and Irish (Celtic) bands. Folk festivals in England are experiencing greatly increased popularity, and the profile of the genre has also grown substantially beyond the boundaries of the conventional 'folk scene' contexts: Seth Lakeman received a Mercury Music Awards nomination in 2006 for his album Kitty Jay; Jim Moray supported Will Young’s 2003 UK tour, and his album Sweet England appeared in the Independent’s ‘Cult Classics’ series in 2007; in 2003, the morris side Dogrose Morris appeared on the popular television music show Later with Jools Holland, accompanied by the high-profile fiddler, Eliza Carthy;1 and all-star festival-headliners Bellowhead appeared on the same show in 2006.2 However, the expansion in the profile and presence of English folk music has 2 not been confined to the realms of vernacular, popular culture: On 20 July 2008, BBC Radio 3 hosted the BBC Proms -

Newsletter 59

SQUIRE: BRIAN TASKER 6 ROOPERS, SPELDHURST, TUNBRIDGE WELLS, KENT, TN3 0QL TEL: 01892 862301 E-mail: [email protected] BAGMAN: CHARLIE CORCORAN 70, GREENGATE LANE, BIRSTALL, LEICESTER, LEICS LE4 3DL TEL: 01162 675654 E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] TREASURER: STEVE ADAMSON BFB 12, FLOCKTON ROAD, EAST BOWLING, BRADFORD, WEST YORKSHIRE BD4 7RH TEL: 01274 773830 E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] The Newsletter No.59 December 2008 The highlights of this Newsletter are: Page Massed Dances and their music 2 Annual Representatives’ Meeting 3 Information about Chris Harris’ “Kemps Jig” 4 ARM Agenda (and advance request for Reports) 6 Joint Morris Organisations: Nottingham Revels 28th March 2009 8 EFDSS News 8 Francis Shergold (1919-2008) A Tribute by Paul Reece 10 Cultural Olympiad 11 2009 Meetings of Morris Ring 11 Treasurer’s ramblings 11 Who’s going to which meeting? 12 Saddleworth Rushcart 2009 12 Jigs Instructional 2009 13 2009 Rapper and Longsword Tournaments 13 Redcar Sword Dancers triumphant again 14 Morris in the Media – Marks for trying? 14 Future Dates 16 Application Forms: Jigs Instructional 19 Morris Ring Meetings 20 Morris Ring Newsletter No 59 December 2008 Page 1 of 20 THE MORRIS RING IS THE NATONAL ASSOCIATION OF MEN’S MORRIS & SWORD DANCE CLUBS Music for Massed Dancing. Following the article in Newsletter No. 58 Harry Winstone, of Kemp's Men, contacted Brian Tasker, Squire of the Morris Ring, and suggested that we need to provide some indication of the tunes to be used. His comment was “50 musicians all playing their own versions. -

Sound Recording in the British Folk Revival: Ideology, Discourse and Practice, 1950–1975

Sound recording in the British folk revival: ideology, discourse and practice, 1950–1975 Matthew Ord Submitted in fulfilment of the degree of PhD International Centre for Music Studies Newcastle University March 2017 Abstract Although recent work in record production studies has advanced scholarly understandings of the contribution of sound recording to musical and social meaning, folk revival scholarship in Britain has yet to benefit from these insights. The revival’s recording practice took in a range of approaches and contexts including radio documentary, commercial studio productions and amateur field recordings. This thesis considers how these practices were mediated by revivalist beliefs and values, how recording was represented in revivalist discourse, and how its semiotic resources were incorporated into multimodal discourses about music, technology and traditional culture. Chapters 1 and 2 consider the role of recording in revivalist constructions of traditional culture and working class communities, contrasting the documentary realism of Topic’s single-mic field recordings with the consciously avant-garde style of the BBC’s Radio Ballads. The remaining three chapters explore how the sound of recorded folk was shaped by a mutually constitutive dialogue with popular music, with recordings constructing traditional performance as an authentic social practice in opposition to an Americanised studio sound equated with commercial/technological mediation. As the discourse of progressive rock elevated recording to an art practice associated with the global counterculture, however, opportunities arose for the incorporation of rock studio techniques in the interpretation of traditional song in the hybrid genre of folk-rock. Changes in studio practice and technical experiments with the semiotics of recorded sound experiments form the subject of the final two chapters. -

Representation Through Music in a Non-Parliamentary Nation

MEDIANZ ! VOL 15, NO 1 ! 2015 DOI: 10.11157/medianz-vol15iss1id8 - ARTICLE - Re-Establishing Britishness / Englishness: Representation Through Music in a non-Parliamentary Nation Robert Burns Abstract The absence of a contemporary English identity distinct from right wing political elements has reinforced negative and apathetic perceptions of English folk culture and tradition among populist media. Negative perceptions such as these have to some extent been countered by the emergence of a post–progressive rock–orientated English folk–protest style that has enabled new folk music fusions to establish themselves in a populist performance medium that attracts a new folk audience. In this way, English politicised folk music has facilitated an English cultural identity that is distinct from negative social and political connotations. A significant contemporary national identity for British folk music in general therefore can be found in contemporary English folk as it is presented in a homogenous mix of popular and world music styles, despite a struggle both for and against European identity as the United Kingdom debates ‘Brexit’, the current term for its possible departure from the EU. My mother was half English and I'm half English too I'm a great big bundle of culture tied up in the red, white and blue (Billy Bragg and the Blokes 2002). When the singer and songwriter, Billy Bragg wrote the above song, England, Half English, a friend asked him whether he was being ironic. He replied ‘Do you know what, I’m not’, a statement which shocked his friends. Bragg is a social commentator, political activist and staunch socialist who is proudly English and an outspoken anti–racist, which his opponents may see as arguably diametrically opposed combination. -

Armandito Y Su Trovason High Energy Cuban Six Piece Latin Band

Dates For Your Diary Folk News Folk Federation of New South Wales Inc Dance News Issue 412 CD Reviews November 2009 $3.00 Armandito Y Su Trovason High energy Cuban six piece Latin band ♫ folk music ♫ dance ♫ festivals ♫ reviews ♫ profiles ♫ diary dates ♫ sessions ♫ teachers ♫ opportunities The Folk Federation ONLINE - jam.org.au The CORNSTALK Gazette NOVEMBER 2009 1 AdVErTISINg Rates Size mm Members Non-mem NOVEMBEr 2009 Folk Federation of New South Wales Inc Full page 180x250 $80 $120 In this issue Post Office Box A182 1/2 page 180x125 $40 $70 Dates for your diary p4 Sydney South NSW 1235 ISSN 0818 7339 ABN9411575922 1/4 page 90x60 $25 $50 Festivals, workshops, schools p6 jam.org.au 1/8 page 45 x 30 $15 $35 Folk news p8 The Folk Federation of NSW Inc, formed in Back cover 180x250 $100 $150 Dance news p9 1970, is a Statewide body which aims to present, Folk contacts p10 support, encourage and collect folk m usic, folk 2 + issues per mth $90 $130 dance, folklore and folk activities as they exist Advertising artwork required by 5th of each month. CD Review p14 Advertisements can be produced by Cornstalk if re- in Australia in all their forms. It provides a link quired. Please contact the editor for enquiries about Deadline for December/January Issue for people interested in the folk arts through its advertising Tel: 6493 6758 ADVERTS 5th November affiliations with folk clubs throughout NSW and its Inserts for Cornstalk COPY 10th November counterparts in other States. It bridges all styles [email protected] NOTE: There will be no January issue. -

UNIVERSAL MUSIC • Rammstein – Videos 1995 – 2012 (DVD) • The

Rammstein – Videos 1995 – 2012 (DVD) The Rolling Stones – Grrr (Album Vinyl Box) Insane Clown Posse – Insane Clown Posse & Twiztid's American Psycho Tour Documentary (DVD) New Releases From Classics And Jazz Inside!! And more… UNI13-03 “Our assets on-line” UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2450 Victoria Park Ave., Suite 1, Willowdale, Ontario M2J 5H3 Phone: (416) 718.4000 Artwork shown may not be final UNIVERSAL MUSIC CANADA NEW RELEASE Artist/Title: Hollywood Undead – Notes From The Underground Bar Code: Cat. #: B001797702 Price Code: SP Order Due: December 20, 2012 Release Date: January 8, 2013 File: Hip Hop /Rock Genre Code: 34/37 Box Lot: 25 SHORT SELL CYCLE Key Tracks: We Are KEY POINTS: 14 BRAND NEW TRACKS Hollywood Undead have sold over 83,000 albums in Canada HEAVY outdoor, radio and online campaign First single “We Are” video is expected mid December 2013 Tour in the works 2.8 million Facebook friends and 166,000 Twitter followers Also Available American Tragedy (2011) ‐ B001527502 Swan Song (2008) ‐ B001133102 INTERNAL USE Label Name: Territory: Choose Release Type: Choose For additional artist information please contact JP Boucher at 416‐718‐4113 or [email protected]. UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2450 Victoria Park Avenue, Suite 1, Toronto, ON M2J 5H3 Phone: (416) 718‐4000 Fax: (416) 718‐4218 UNIVERSAL MUSIC CANADA NEW RELEASE Artist/Title: Black Veil Brides / Wretched And Divine: The Story Of Bar Code: The Wild Ones (Regular CD) Cat. #: B001781702 Price Code: SP 02537 22095 Order Due: Dec. 20, 2012 Release Date: Jan. 8, 2013 6 3 File: Rock Genre Code: 37 Box Lot: 25 Short Sell Cycle Key Tracks: Artist/Title: Black Veil Brides / Wretched And Divine: The Story Of Bar Code: The Wild Ones (Deluxe CD/DVD) Cat. -

The Companion to the 2015 Edington Music Festival

The Companion to THE EDINGTON MUSIC FESTIVAL A festival of music within the liturgy 23-30 AUGUST 2015 The PRioRy ChuRch of Saint MaRy, Saint KathaRine and All SaintS Edington, WeStbuRy, WiltShiRe THE COM PANION TO THE ED I NGTON MUSIC FESTI VAL Sunday 23 to Sunday 30 AuguSt 2015 Contents Introduction Benjamin Nicholas IntRoduction page 3 FoR Some, the fiRSt Edington MuSic FeStival in AuguSt 1956 iS Still within FeStival and geneRal infoRmation page 6 living memoRy, and it haS been wondeRful to heaR fRom Some of the SingeRS FeStival paRticipantS page 10 who weRe involved in that veRy fiRSt feStival. WhilSt the woRld outSide iS veRy, ORdeRS of SeRvice, textS and tRanSlationS page 12 veRy diffeRent, the puRpoSe of thiS unique week RemainS veRy much the Same: David TRendell page 48 a feStival of muSic within the lituRgy Sung by SingeRS fRom the fineSt CathedRal SiR David & Lady BaRbaRa Calcutt page 50 and collegiate choiRS in the land. It iS veRy good to welcome you to the Sixty yeaRS of Edington page 52 Diamond Jubilee FeStival. The Edington MuSic FeStival—commiSSioned woRkS page 54 TheRe haS been plenty to celebRate in Recent feStivalS, and the dedication of BiogRaphieS page 56 the new HaRRiSon & HaRRiSon oRgan laSt yeaR iS Still veRy much in ouR mindS. FeStival PaRticipantS fRom 1956 page 59 It may be no SuRpRiSe that the theme thiS yeaR iS inSpiRed by a cycle of oRgan woRkS by the oRganiSt-compoSeR Jean-LouiS FloRentz. The Seven movementS of hiS Suite LaUdes have influenced the StRuctuRe of the week: A call to prayer , Incantation , Sacred dance , Meditation , Sacred song , Procession and Hymn . -

14302 76969 1 1>

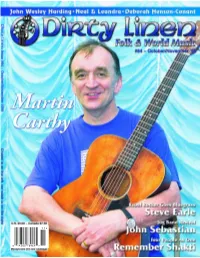

11> 0514302 76969 establishment,” he hastened to clarify. “I wish it were called the Legion of Honour, but it’s not.” Still in all, he thinks it’s good for govern- M artin C arthy ments to give cultural awards and is suitably honored by this one, which has previously gone to such outstanding folk performers as Jeannie Robertson. To decline under such circum- stances, he said, would have been “snotty.” Don’t More importantly, he conceives of his MBE as recognition he shares with the whole Call Me folk scene. “I’ve been put at the front of a very, very long queue of people who work hard to make a folk revival and a folk scene,” he said. Sir! “All those people who organized clubs for nothing and paid you out of their own pocket, and fed you and put you on the train the next morning, and put you to bed when you were drunk! What [the government is] doing, is taking notice of the fact that something’s going on for the last more than 40 years. It’s called the folk revival. They’ve ignored it for that long. And someone has suddenly taken notice, and that’s okay. A bit of profile isn’t gonna hurt us — and I say us, the plural, for the folk scene — isn’t gonna hurt us at all.” In the same year as Carthy’s moment of recognition, something happened that did hurt the folk scene. Lal Waterson, Carthy’s sister-in- law, bandmate, near neighbor and close friend, died of cancer. -

International Journal of Education & the Arts

International Journal of Education & the Arts Editors Eeva Anttila Terry Barrett University of the Arts Helsinki University of North Texas William J. Doan S. Alex Ruthmann Pennsylvania State University New York University http://www.ijea.org/ ISSN: 1529-8094 Volume 15 Number 19 November 1, 2014 Deepening Inquiry: What Processes of Making Music Can Teach Us about Creativity and Ontology for Inquiry Based Science Education Walter S. Gershon Kent State University, U. S. Oded Ben-Horin Stord/Haugesund University College, Norway Citation: Gershon, W. S., & Ben-Horin, O. (2014). Deepening inquiry: What processes of making music can teach us about creativity and ontology for inquiry based science education. International Journal of Education & the Arts, 15(19). Retrieved from http://www.ijea.org/v15n19/. Abstract Drawing from their respective work at the intersection of music and science, the co- authors argue that engaging in processes of making music can help students more deeply engage in the kinds of creativity associated with inquiry based science education (IBSE) and scientists better convey their ideas to others. Of equal importance, the processes of music making can provide students a means to experience another central aspect of IBSE, the liminal ontological experience of being utterly lost in the inquiry process. This piece is also part of burgeoning studies documenting the use of the arts in STEM education (STEAM). IJEA Vol. 15 No. 19 - http://www.ijea.org/v15n19/ 2 Principles for the Development of a Complete Mind: Study the science of art. Study the art of science. Develop your senses – especially learn how to see.