Folk for Art's Sake: English Folk Music in the Mainstream Milieu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SUMMER/AUTUMN 2012 No. 99

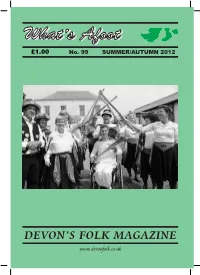

cover.pdf 1 03/11/2009 12:03:39 what’s afoot title & logo to be inserted as for previous issues. No. 99 SUMMER/AUTUMN 2012 £1.00 No. 99 SUMMER/AUTUMN 2012 The Magazine of Devon Folk www.devonfolk.co.uk All articles, letters, photos, and diary What’s Afoot No. 99 dates & listings Contents Local Treasures: Paul Wilson & Marilyn Tucker 4 diary entries free Body and Soul 7 Please send to Keep Fit & Healthy The Fun Way 9 Colin Andrews Obituaries 10 Bonny Green, Lucky 7’s Thanks to Peter & Margaret 13 Morchard Bishop, Footnotes 14 Crediton, EX17 6PG Poetic Playford 15 Tel/fax 01363 877216 Devon Folk News 16 [email protected] Devon Folk Committee 18 Contacts: dance, music & song clubs 19 - 23 Copy Dates Diary Dates 25 - 30 1st Feb for 1st April Contacts: display, festivals, bands, callers 33 - 37 1st June for 1st Aug Reviews 38 - 45 1st Oct for 1st Dec D’Urfey and O’Carolan 46 Advertising Finding My Voice Early Years Music project 49 Morris Matters 50 Enquiries & copy to: Dick Little The search for my replacement as editor of What’s Afoot may be Collaton Grange, over. Having twisted quite a few arms over the past few months, to Malborough. no avail, a volunteer (!) has come forward. Sue Hamer-Moss is an Kingsbridge TQ7 3DJ experienced folk dance caller and Morris dancer with Winkleigh Tel/fax 01548 561352 (3rd from left on front cover), Jackstraws & Downs on Tour. She [email protected] was an originl member of Glory of the West. -

Amjad Ali Khan & Sharon Isbin

SUMMER 2 0 2 1 Contents 2 Welcome to Caramoor / Letter from the CEO and Chairman 3 Summer 2021 Calendar 8 Eat, Drink, & Listen! 9 Playing to Caramoor’s Strengths by Kathy Schuman 12 Meet Caramoor’s new CEO, Edward J. Lewis III 14 Introducing in“C”, Trimpin’s new sound art sculpture 17 Updating the Rosen House for the 2021 Season by Roanne Wilcox PROGRAM PAGES 20 Highlights from Our Recent Special Events 22 Become a Member 24 Thank You to Our Donors 32 Thank You to Our Volunteers 33 Caramoor Leadership 34 Caramoor Staff Cover Photo: Gabe Palacio ©2021 Caramoor Center for Music & the Arts General Information 914.232.5035 149 Girdle Ridge Road Box Office 914.232.1252 PO Box 816 caramoor.org Katonah, NY 10536 Program Magazine Staff Caramoor Grounds & Performance Photos Laura Schiller, Publications Editor Gabe Palacio Photography, Katonah, NY Adam Neumann, aanstudio.com, Design gabepalacio.com Tahra Delfin,Vice President & Chief Marketing Officer Brittany Laughlin, Director of Marketing & Communications Roslyn Wertheimer, Marketing Manager Sean Jones, Marketing Coordinator Caramoor / 1 Dear Friends, It is with great joy and excitement that we welcome you back to Caramoor for our Summer 2021 season. We are so grateful that you have chosen to join us for the return of live concerts as we reopen our Venetian Theater and beautiful grounds to the public. We are thrilled to present a full summer of 35 live in-person performances – seven weeks of the ‘official’ season followed by two post-season concert series. This season we are proud to showcase our commitment to adventurous programming, including two Caramoor-commissioned world premieres, three U.S. -

Folk Song in Cumbria: a Distinctive Regional

FOLK SONG IN CUMBRIA: A DISTINCTIVE REGIONAL REPERTOIRE? A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Susan Margaret Allan, MA (Lancaster), BEd (London) University of Lancaster, November 2016 ABSTRACT One of the lacunae of traditional music scholarship in England has been the lack of systematic study of folk song and its performance in discrete geographical areas. This thesis endeavours to address this gap in knowledge for one region through a study of Cumbrian folk song and its performance over the past two hundred years. Although primarily a social history of popular culture, with some elements of ethnography and a little musicology, it is also a participant-observer study from the personal perspective of one who has performed and collected Cumbrian folk songs for some forty years. The principal task has been to research and present the folk songs known to have been published or performed in Cumbria since circa 1900, designated as the Cumbrian Folk Song Corpus: a body of 515 songs from 1010 different sources, including manuscripts, print, recordings and broadcasts. The thesis begins with the history of the best-known Cumbrian folk song, ‘D’Ye Ken John Peel’ from its date of composition around 1830 through to the late twentieth century. From this narrative the main themes of the thesis are drawn out: the problem of defining ‘folk song’, given its eclectic nature; the role of the various collectors, mediators and performers of folk songs over the years, including myself; the range of different contexts in which the songs have been performed, and by whom; the vexed questions of ‘authenticity’ and ‘invented tradition’, and the extent to which this repertoire is a distinctive regional one. -

Steve Harley Lee Nelson

SPARKLING ARTS EVENTS IN THE HEART OF SHOREHAM SEPT – DEC 2014 BAKA BEYOND LUNASA THE INNER VISION ORCHESTRA STEVE HARLEY GEORGIE FAME LEE NELSON TOYAH WILLCOX CURVED AIR SHAKATAK ROPETACKLECENTRE.CO.UK SEPT 2014 ropetacklecentre.co.uk BOX OFFICE: 01273 464440 SEPT 2014 WELCOME TO ROPETACKLE From music, comedy, theatre, talks, family events, exhibitions, and much more, we’ve something for everybody to enjoy this autumn and winter. As a charitable trust staffed almost entirely by volunteers, nothing comes close to the friendly atmosphere, intimate performance space, and first- class programming that makes Ropetackle one of the South Coast’s most prominent and celebrated arts venues. We believe engagement with the arts is of vital importance to the wellbeing of both individuals and the community, and with such an exciting and eclectic programme ahead of us, we’ll let the events speak for themselves. See you at the bar! THUNKSHOP THURSDAY SUPPERS BOX OFFICE: 01273 464440 Our in-house cafe Thunkshop will be serving delicious pre-show suppers from 6pm before most of our Thursday events. Advance With support from booking is recommended but not essential, please contact Sarah on 07957 166092 for further details and to book. Seats are reserved for people dining. Look out for the Thunkshop icon throughout the programme or visit page 58 for the full list of pre-show meals. Programme design by Door 22 Creative www.door22.co.uk @ropetackleart Ropetackle Arts Centre Opera Rock Folk Family Blues Spoken Word Jazz 2 SEPT 2014 ropetacklecentre.co.uk BOX OFFICE: 01273 464440 SEPT 2014 SARA SPADE & THE NOISY BOYS Sara Spade & The Noisy Boys: World War One Centenary Concert She’s back! After a sell-out Ropetackle show in January, Sara Spade & The Noisy Boys return with flapper classics like ‘Five Foot Two, Eyes of Blue’ and other popular Charlestons, plus favourite Great War-era songs including Pack up your Troubles in your Old Kit Bag and Long Way to Tipperary. -

Fall Folk Music Weekend October 17-19 -- See Flyer in Centerfold Table of Contents Society Events Details

Folk Music Society of New York, Inc. September 2008 vol 43, No.8 September 3 Wed Folk Open Sing, 7pm in Brooklyn 8 Mon FMSNY Exec. Board Meeting; 7:15pm location tba 13 Sat Chantey Sing at Seamen’s Church Institute, 8pm. 19 Fri Jeff Warner, 8pm, in Forest Hills, Queens 21 Sun Sacred Harp Singing at St.Bartholomew’s in Manhattan 21 Sun Jeff Warner house concert, 2pm in Sparrowbush, NY October 1 Wed Folk Open Sing 7 pm in Brooklyn 2 Thur Newsletter Mailing, 7pm in Jackson Heights (Queens). 5 Sun Sea Music: tba + NY Packet; 3pm,South St 10 Fri Bob Malenky house concert, 8pm upper west side 11 Sat Chantey Sing at Seamen’s Church Institute, 8pm. 13 Mon FMSNY Exec. Board Meeting; 7:15pm location tba 17-19 Fall Folk Muisc Weekend in Ellenville, NY-- see centerfold 19 Sun Sacred Harp Singing at St.Bartholomew’s in Manhattan 24 Fri Svitanya, vocal workshop 6:30pm; concert 8pm at OSA J; A Daniel Pearl World Music Days Concert Details next pages -- Table of Contents below Fall Folk Music Weekend October 17-19 -- see flyer in Centerfold Table of Contents Society Events details ............2-3 Repeating Events ...................13 Folk Music Society Info ........... 4 Calendar Location Info ...........16 Topical Listing of Events .......... 5 Perples’ Voice Ad ..................18 Weekend Help Wanted ............ 6 FSSGB Weekend Ad ..............18 From The Editor .................... 6 30 Years Ago ......................18 Jeff Warner Concerts ............... 7 Pinewoods Hot Line ..............19 Eisteddfod-NY ....................8-9 Membership Form .................20 Film Festival ........................10 Folk Process ....................... 11 Weekend Flyer ........... centerfold Calendar Listings ................ -

Download PDF Booklet

“I am one of the last of a small tribe of troubadours who still believe that life is a beautiful and exciting journey with a purpose and grace well worth singing about.” E Y Harburg Purpose + Grace started as a list of songs and a list of possible guests. It is a wide mixture of material, from a traditional song I first heard 50 years ago, other songs that have been with me for decades, waiting to be arranged, to new original songs. You stand in a long line when you perform songs like this, you honour the ancestors, but hopefully the songs become, if only briefly your own, or a part of you. To call on my friends and peers to make this recording has been a great pleasure. Turning the two lists into a coherent whole was joyous. On previous recordings I’ve invited guest musicians to play their instruments, here, I asked singers for their unique contributions to these songs. Accompanying song has always been my favourite occupation, so it made perfect sense to have vocal and instrumental collaborations. In 1976 I had just released my first album and had been picked up by a heavy, old school music business manager whose avowed intent was to make me a star. I was not averse to the concept, and went straight from small folk clubs to opening shows for Steeleye Span at the biggest halls in the country. Early the next year June Tabor asked me if I would accompany her on tour. I was ecstatic and duly reported to my manager, who told me I was a star and didn’t play for other people. -

BFMS Newsletter 2004-12.Indd

BALTIMORE FOLK MUSIC SOCIETY Member, Country Dance & Song Society www.bfms.org December 2004 Somebody Scream Productions Sponsored by BFMS and CCBC/CC Offi ce of Student Events presents Dikki Du and the Zydeco Crew Dikki Du returns to Catonsville with his Zydeco Crew of family and friends to provide rhythmic, hard driving music for your dancing pleasure. It should be known that Dikki (aka Troy) is the son of Roy Carrier, brother to Chubby Carrier and cousin to Dwight Carrier. Needless to say talent runs in the family! He impressed at Buff alo Jambalaya this year as he backed two bands on drums and also showed us his love of accordion. Admission: $12/$10 BFMS members/$5 CCBC/CC students with ID. Free, well-lit parking is available. Directions: From I-95, take exit 47 (Route 195). Follow signs for Route 166. Turn right onto Route 166 North (Rolling Road) towards Catonsville. At the second traffi c light (Valley Road), turn left into Catonsville Community College campus. Th e Barn Th eater is the stone building on the hill beyond parking lot A. Info: [email protected], www.WhereWeGoTo- Zydeco.com Th e Barn Th eater Catonsville Community College, Catonsville Saturday, Dec. 4, Dance lesson: 8 pm Music: 9 pm–midnight BFMS American Contra and Square Dance Dec. 1 Dec. 29 Sue Dupre with Sugar Beat: Susan Brandt (fl ute), Marc Glick- Open Band Night with caller Bob Hofkin. man (piano), and Elke Baker (fi ddle). Lovely Lane Church Dec. 8 2200 St. Paul St., Baltimore Steve Gester with the Altered Gardeners: Dave Weisler (piano, guitar), Alexander Mitchell (fi ddle), and George Paul (piano, Wednesday evenings, 8–11 pm accordion). -

Representation Through Music in a Non-Parliamentary Nation

MEDIANZ ! VOL 15, NO 1 ! 2015 DOI: 10.11157/medianz-vol15iss1id8 - ARTICLE - Re-Establishing Britishness / Englishness: Representation Through Music in a non-Parliamentary Nation Robert Burns Abstract The absence of a contemporary English identity distinct from right wing political elements has reinforced negative and apathetic perceptions of English folk culture and tradition among populist media. Negative perceptions such as these have to some extent been countered by the emergence of a post–progressive rock–orientated English folk–protest style that has enabled new folk music fusions to establish themselves in a populist performance medium that attracts a new folk audience. In this way, English politicised folk music has facilitated an English cultural identity that is distinct from negative social and political connotations. A significant contemporary national identity for British folk music in general therefore can be found in contemporary English folk as it is presented in a homogenous mix of popular and world music styles, despite a struggle both for and against European identity as the United Kingdom debates ‘Brexit’, the current term for its possible departure from the EU. My mother was half English and I'm half English too I'm a great big bundle of culture tied up in the red, white and blue (Billy Bragg and the Blokes 2002). When the singer and songwriter, Billy Bragg wrote the above song, England, Half English, a friend asked him whether he was being ironic. He replied ‘Do you know what, I’m not’, a statement which shocked his friends. Bragg is a social commentator, political activist and staunch socialist who is proudly English and an outspoken anti–racist, which his opponents may see as arguably diametrically opposed combination. -

Jahresauswahl Globalwize 2011

Globalwize Best of 2011 01. Kääme >>>Andrew Cronshaw: The Unbroken Surface of Snow (Cloud Valley Music/ www.cloudvalley.com/ www.andrewcronshaw.com ) 02. Heptimo >>>Dancas Ocultas: Tarab (Numérica/Galileo MC/ www.dancasocultas.com ) 03. Quérom’ire >>>Uxía: Danzas das Areas (Fol/Galileo MC/ www.uxia.net / www.folmusica.com ) 04. Hold Me In >>>Lucas Santtana: Sem Nostalgia (Mais Um Discos/Indigo/ www.maisumdiscos.com ) 05. She was >>>Camille: Ilo veyou (EMI France/Capitol Records/ www.camille-music.com ) 06. Pharizm >>>Bratsch: Urban Bratsch (World Village/Harmonia Mundi/ www.worldvillagemusic.com / www.bratsch.com ) 07. Nign for Sabbath & Holidays >>>Joel Rubin & Uri Caine Duo: Azoy Tsu Tsveyt (Tzadik/ SunnyMoon) 08. March of the Jobless Corps / Arbeitzlozer Marsh >>>Daniel Kahn & The Painted Bird: Lost Causes Songbook (Oriente Musik/ www.oriente.de / www.paintedbird.net ) 09. Opa Cupa >>>Söndörgö: Tamburising (World Village/Harmonia Mundi/ www.worldvillagemusic.com / www.sondorgo.hu ) 10. Yarmouth Town >>> Bellowhead: Hedonism (Navigator Records/PIAS/ www.bellowhead.co.uk ) 11. The Leaves of Life >>>June Tabor & Oysterband: Ragged Kingdom (Westpark Music/Indigo/ www.westparkmusic.de / www.osterband.co.uk ) 12. L’immagine di te >>>Radio Dervish con Livio Minafra & La Banda Di Sannicandro di Bari: Bandervish (Princigalli/ www.radiodervish.com ) 13. Insintesi feat. Alessia Toondo: Pizzica di Aredo >>> Insintesi Salento in Dub (Anima Mundi/ www.suonidalmundo.com ) 14. Beddhu Stanotte >>>Canzionere grecanico salentino: Focu d’amore (Ponderosa Music/ www.canzonieregrecanicosalentino.net ) 15. Shiner Hobo Band: Grinders Polka >>>V.A. (Hrsg. Thomas Meinecke): Texas Bohemia Revisited (Trikont/Indigo/ www.trikont.de ) 16. So Glad >>>Hazmat Modine: Cicada (Jaro/ www.jaro.de / www.hazmatmodine.com) 17. -

Alumnews2007

C o l l e g e o f L e t t e r s & S c i e n c e U n i v e r s i t y D EPARTMENT o f o f C a l i f o r n i a B e r k e l e y MUSIC IN THIS ISSUE Alumni Newsletter S e p t e m b e r 2 0 0 7 1–2 Special Occasions Special Occasions CELEBRATIONS 2–4 Events, Visitors, Alumni n November 8, 2006, the department honored emeritus professor Andrew Imbrie in the year of his 85th birthday 4 Faculty Awards Owith a noon concert in Hertz Hall. Alumna Rae Imamura and world-famous Japanese pianist Aki Takahashi performed pieces by Imbrie, including the world premiere of a solo piano piece that 5–6 Faculty Update he wrote for his son, as well as compositions by former Imbrie Aki Takahashi performss in Hertz Hall student, alumna Hi Kyung Kim (professor of music at UC Santa to honor Andrew Imbrie. 7 Striggio Mass of 1567 Cruz), and composers Toru Takemitsu and Michio Mamiya, with whom Imbrie connected in “his Japan years.” The concert was followed by a lunch in Imbrie’s honor in Hertz Hall’s Green Room. 7–8 Retirements Andrew Imbrie was a distinguished and award-winning member of the Berkeley faculty from 1949 until his retirement in 1991. His works include five string quartets, three symphonies, numerous concerti, many works for chamber ensembles, solo instruments, piano, and chorus. His opera Angle of 8–9 In Memoriam Repose, based on Wallace Stegner’s book, was premeiered by the San Francisco Opera in 1976. -

UNIVERSAL MUSIC • Rammstein – Videos 1995 – 2012 (DVD) • The

Rammstein – Videos 1995 – 2012 (DVD) The Rolling Stones – Grrr (Album Vinyl Box) Insane Clown Posse – Insane Clown Posse & Twiztid's American Psycho Tour Documentary (DVD) New Releases From Classics And Jazz Inside!! And more… UNI13-03 “Our assets on-line” UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2450 Victoria Park Ave., Suite 1, Willowdale, Ontario M2J 5H3 Phone: (416) 718.4000 Artwork shown may not be final UNIVERSAL MUSIC CANADA NEW RELEASE Artist/Title: Hollywood Undead – Notes From The Underground Bar Code: Cat. #: B001797702 Price Code: SP Order Due: December 20, 2012 Release Date: January 8, 2013 File: Hip Hop /Rock Genre Code: 34/37 Box Lot: 25 SHORT SELL CYCLE Key Tracks: We Are KEY POINTS: 14 BRAND NEW TRACKS Hollywood Undead have sold over 83,000 albums in Canada HEAVY outdoor, radio and online campaign First single “We Are” video is expected mid December 2013 Tour in the works 2.8 million Facebook friends and 166,000 Twitter followers Also Available American Tragedy (2011) ‐ B001527502 Swan Song (2008) ‐ B001133102 INTERNAL USE Label Name: Territory: Choose Release Type: Choose For additional artist information please contact JP Boucher at 416‐718‐4113 or [email protected]. UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2450 Victoria Park Avenue, Suite 1, Toronto, ON M2J 5H3 Phone: (416) 718‐4000 Fax: (416) 718‐4218 UNIVERSAL MUSIC CANADA NEW RELEASE Artist/Title: Black Veil Brides / Wretched And Divine: The Story Of Bar Code: The Wild Ones (Regular CD) Cat. #: B001781702 Price Code: SP 02537 22095 Order Due: Dec. 20, 2012 Release Date: Jan. 8, 2013 6 3 File: Rock Genre Code: 37 Box Lot: 25 Short Sell Cycle Key Tracks: Artist/Title: Black Veil Brides / Wretched And Divine: The Story Of Bar Code: The Wild Ones (Deluxe CD/DVD) Cat. -

At the Turning Wave Festival from Ireland Caoimhin O’Raghallaigh Eithne Ni Cháthain Enda O’Cathain

Dates For Your Diary Folk News Folk Federation of New South Wales Dance News Inc CD Reviews Issue 401 NOVEMBER 2008 $3 At the Turning Wave Festival from Ireland Caoimhin O’Raghallaigh Eithne Ni Cháthain Enda O’Cathain ♫ folk music ♫ dance ♫ festivals ♫ reviews ♫ profiles ♫ diary dates ♫ sessions ♫The Folkteachers Federation ONLINE ♫ - jam.org.au opportunitiesThe CORNSTALK Gazette NOVEMBER 2008 1 AdvErTISINg Rates Size mm Members Non-mem November 2008 Full page 180x250 $80 $120 In this issue Folk Federation of New South Wales Inc Post Office Box A182 1/2 page 180x125 $40 $70 Dates for your diary p4 Sydney South NSW 1235 1/4 page 90x60 $25 $50 Festivals, workshops, schools p6 ISSN 0818 7339 ABN9411575922 jam.org.au 1/8 page 45 x 30 $15 $35 Folk news p7 Cornstalk Editor - Coral Vorbach Back cover 180x250 $100 $150 Dance news p7 Post Office Box 5195. Cobargo NSW 2550 2 + issues per mth $90 $130 Folk contacts p8 Tel/Fax: 02 6493 6758 Advertising artwork required by 5th Friday of month. Industry Insights (Nick Charles) p11 Email: [email protected] Advertisements can be produced by Cornstalk if re- Cornstalk is the official publication of the Folk quired. Please contact the editor for enquiries about Inside Acoustic Music - Recording a live Federation of NSW. Contributions, news, reviews, advertising Tel: 6493 6758 CD by Sue Barratt (Part 4 (final) ) p12 poems, photographs most welcome. Inserts for Cornstalk Front cover photograph courtesy Jane Photographs and Artwork [email protected] Harding Photographs - high resolution JPG or TIFF files. Insert rates: DEADLINE December/Jan Adverts - 5th 300 dpi images cropped at correct size.