Folk Song in Cumbria: a Distinctive Regional

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View Or Download Full Colour Catalogue May 2021

VIEW OR DOWNLOAD FULL COLOUR CATALOGUE 1986 — 2021 CELEBRATING 35 YEARS Ian Green - Elaine Sunter Managing Director Accounts, Royalties & Promotion & Promotion. ([email protected]) ([email protected]) Orders & General Enquiries To:- Tel (0)1875 814155 email - [email protected] • Website – www.greentrax.com GREENTRAX RECORDINGS LIMITED Cockenzie Business Centre Edinburgh Road, Cockenzie, East Lothian Scotland EH32 0XL tel : 01875 814155 / fax : 01875 813545 THIS IS OUR DOWNLOAD AND VIEW FULL COLOUR CATALOGUE FOR DETAILS OF AVAILABILITY AND ON WHICH FORMATS (CD AND OR DOWNLOAD/STREAMING) SEE OUR DOWNLOAD TEXT (NUMERICAL LIST) CATALOGUE (BELOW). AWARDS AND HONOURS BESTOWED ON GREENTRAX RECORDINGS AND Dr IAN GREEN Honorary Degree of Doctorate of Music from the Royal Conservatoire, Glasgow (Ian Green) Scots Trad Awards – The Hamish Henderson Award for Services to Traditional Music (Ian Green) Scots Trad Awards – Hall of Fame (Ian Green) East Lothian Business Annual Achievement Award For Good Business Practises (Greentrax Recordings) Midlothian and East Lothian Chamber of Commerce – Local Business Hero Award (Ian Green and Greentrax Recordings) Hands Up For Trad – Landmark Award (Greentrax Recordings) Featured on Scottish Television’s ‘Artery’ Series (Ian Green and Greentrax Recordings) Honorary Member of The Traditional Music and Song Association of Scotland and Haddington Pipe Band (Ian Green) ‘Fuzz to Folk – Trax of My Life’ – Biography of Ian Green Published by Luath Press. Music Type Groups : Traditional & Contemporary, Instrumental -

Cumbrian Railway Ancestors B Surnames Surname First Names

Cumbrian Railway Ancestors B surnames Year Age Surname First names Employment Location Company Date Notes entered entered Source service service Babbs John Porter Barrow Goods FUR 08/08/1895 Entered service on 20/- pw 1895 26 FR Staff Register Babbs John Parcels Porter Barrow Central FUR 25/06/1900 From Barrow Goods on 22/- pw 1895 26 FR Staff Register Babbs John Labourer Buccleuch Jct to Goods Dep FUR 16/09/1907 Entered service 1907 38 Furness PW staff register p 6 Babbs John P.Way Askam FUR 00/03/1908 AMB Listed as available mobilisation for Babbs John P Way Labourer Askam FUR 06/08/1914 RAIL 214/81 entrenchmen works Babe William Signalman Carlisle MID 14/11/1876 New appointment. Still in post in 1898 RAIL 491/1024 Babe William Signalman Carlisle MID 00/00/1902 Died RAIL 491/1026 Backhouse James Porter Barrow ? FUR 00/00/1851 Age 32 b.Whitehall Census Backhouse Luke Clerk Askam FUR 10/10/1881 Entered service on 5/6 pw 1881 15 FR Staff Register Transferred from Askam Iron Works on Backhouse Luke Office Boy Dalton FUR 15/05/1882 1881 15 FR Staff Register 7/6 pw Backhouse Luke Clerk Foxfield FUR 20/02/1883 Transferred from Dalton on 10/- pw 1881 15 FR Staff Register Backhouse Luke Clerk Ulverston FUR 29/10/1883 Transferred from Foxfield on 12/6 pw 1880 15 FR Staff Register Backhouse Luke Clerk Ulverston FUR 08/05/1886 Resigned 1880 15 FR Staff Register Backhouse R Underman Lake Side LMS 05/05/1928 In service with LMS on May 5 1928 Furness PW staff register p 26,25 Bacon A. -

LD19 Carlisle City Local Plan 2001-2016

Carlisle District Local Plan 2001 - 2016 Written Statement September 2008 Carlisle District Local Plan 2001-2016 Written Statement September 2008 If you wish to contact the City Council about this plan write to: Local Plans and Conservation Manager Planning and Housing Services Civic Centre Carlisle CA3 8QG tel: 01228 817193 fax: 01228 817199 e-mail: [email protected] This document can also be viewed on the Council’s website: www.carlisle.gov.uk/localplans A large print or audio version is also available on request from the above address Cover photos © Carlisle City Council; CHedley (Building site), CHedley (Irish Gate Bridge), Cumbria County Council (Wind turbines) Carlisle District Local Plan 2001-16 2 September 2008 Contents Chapter 1 Introduction Purpose of the Local Plan ........................................................................................ 5 Format of the Local Plan .......................................................................................... 5 Planning Context ....................................................................................................... 6 The Preparation Process ........................................................................................... 6 Chapter 2 Spatial Strategy and Development Principles The Vision ..................................................................................................................... 9 The Spatial Context ................................................................................................... 9 A Sustainable Strategy -

Technical Paper 5

Planning Cumbria Cumbria and Lake District Joint Structure Plan 2001 – 2016 Technical Paper 5 Landscape Character Preface to Technical Paper 5 Landscape Character 1. The Deposit Structure Plan includes a policy (Policy E33) on landscape character, while the term landscape character is also used in other policies. It is important that there is clear understanding of this term and how it is to be applied in policy terms. 2. This report has been commissioned by the County Council from CAPITA Infrastructure Consultancy in Carlisle. It is currently not endorsed by the County Council. On receipt of comments the County Council will re draft the report and then publish it as a County Council document. The final version will replace two previous publications: Technical paper No 4 (1992) on the Assessment of County Landscapes and the Cumbria Landscapes Classification (1995). 3. The report explains how landscape has been characterised in Cumbria (outside the National Parks) using landscape types and provides details of the classification into 37 landscape types and sub types. A recent review of the classification of County Landscapes (now termed Landscapes of County Importance) and their detailed boundaries are also included. 4. It should be noted that this report does not constitute Structure Plan Policy. It provides background information to enable the policy to be implemented and monitored. 5. Comments on this report should be sent to: Mike Smith Countryside and Landscape Officer Cumbria County Council County Offices Kendal Cumbria LA9 4RQ Tel: -

The Lakes Tour 2015

A survey of the status of the lakes of the English Lake District: The Lakes Tour 2015 S.C. Maberly, M.M. De Ville, S.J. Thackeray, D. Ciar, M. Clarke, J.M. Fletcher, J.B. James, P. Keenan, E.B. Mackay, M. Patel, B. Tanna, I.J. Winfield Lake Ecosystems Group and Analytical Chemistry Centre for Ecology & Hydrology, Lancaster UK & K. Bell, R. Clark, A. Jackson, J. Muir, P. Ramsden, J. Thompson, H. Titterington, P. Webb Environment Agency North-West Region, North Area History & geography of the Lakes Tour °Started by FBA in an ad hoc way: some data from 1950s, 1960s & 1970s °FBA 1984 ‘Tour’ first nearly- standardised tour (but no data on Chl a & patchy Secchi depth) °Subsequent standardised Tours by IFE/CEH/EA in 1991, 1995, 2000, 2005, 2010 and most recently 2015 Seven lakes in the fortnightly CEH long-term monitoring programme The additional thirteen lakes in the Lakes Tour What the tour involves… ° 20 lake basins ° Four visits per year (Jan, Apr, Jul and Oct) ° Standardised measurements: - Profiles of temperature and oxygen - Secchi depth - pH, alkalinity and major anions and cations - Plant nutrients (TP, SRP, nitrate, ammonium, silicate) - Phytoplankton chlorophyll a, abundance & species composition - Zooplankton abundance and species composition ° Since 2010 - heavy metals - micro-organics (pesticides & herbicides) - review of fish populations Wastwater Ennerdale Water Buttermere Brothers Water Thirlmere Haweswater Crummock Water Coniston Water North Basin of Ullswater Derwent Water Windermere Rydal Water South Basin of Windermere Bassenthwaite Lake Grasmere Loweswater Loughrigg Tarn Esthwaite Water Elterwater Blelham Tarn Variable geology- variable lakes Variable lake morphometry & chemistry Lake volume (Mm 3) Max or mean depth (m) Mean retention time (day) Alkalinity (mequiv m3) Exploiting the spatial patterns across lakes for science Photo I.J. -

TWO VALLEYS PARISH NEWS April 2018

TWO VALLEYS PARISH NEWS www.crosthwaiteandlyth.co.uk/twovalleys Serving the parishes of Cartmel Fell, Crook, Crosthwaite, Helsington, Underbarrow, Winster, & Witherslack April 2018 70p Holme Crag Garden Party INTRIGUINGLY beautiful gardens which took over 30 years to nurture from rock and rugged land are open on Sunday, May 20th in Witherslack. Featured in Tim Longville’s acclaimed “Gardens of the Lake District”, Holme Crag is opening its gates as a fund-raiser for St. Paul’s Parish Church. Appearing on television, loved my many who have visited the magical place, the garden is testimony to the late Jack Watson’s vision of ‘merely cultivating ecology’. A magnet for birds, wild animals and insects, this where a lovely, untamed landscape meets decades of graft, and Jack's passion for planting, to create a unique and beguiling spectacle. By late spring, pond-side astilbes and hostas may be pushing through, rhododendrons still flowering and Holme Crag’s Candelabra primulas in their first ascent. Many of the plants and trees were established to encourage wildlife and the garden is noted for a rich variety of birds. Please join us for cream teas, raffles, plants, cakes, white elephant, a selection of stalls and, of course, the garden exploration. Running from 2 to 5pm, entrance is £3, children free. Please follow parking guidelines. Cover photograph from Karen Barden, Holme Crag Church miniature pictures from watercolours by John Wilcock 2 Church Services for APRIL 2018 1st April EASTER DAY 9.30am Cartmel Fell Easter Communion (BCP) Rev. Michelle Woodcock 9.30am Helsington Easter Communion (CW) Canon Michael Middleton 9.30am Underbarrow Easter Communion (CW) Rev. -

Annual Report for the Year Ended the 31St March, 1963

Twelfth Annual Report for the year ended the 31st March, 1963 Item Type monograph Publisher Cumberland River Board Download date 01/10/2021 01:06:39 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/26916 CUMBERLAND RIVER BOARD Twelfth Annual Report for the Year ended the 31st March, 1963 CUMBERLAND RIVER BOARD Twelfth Annual Report for the Year ended the 31st March, 1963 Chairman of the Board: Major EDWIN THOMPSON, O.B.E., F.L.A.S. Vice-Chairman: Major CHARLES SPENCER RICHARD GRAHAM RIVER BOARD HOUSE, LONDON ROAD, CARLISLE, CUMBERLAND. TELEPHONE CARLISLE 25151/2 NOTE The Cumberland River Board Area was defined by the Cumberland River Board Area Order, 1950, (S.I. 1950, No. 1881) made on 26th October, 1950. The Cumberland River Board was constituted by the Cumberland River Board Constitution Order, 1951, (S.I. 1951, No. 30). The appointed day on which the Board became responsible for the exercise of the functions under the River Boards Act, 1948, was 1st April, 1951. CONTENTS Page General — Membership Statutory and Standing Committees 4 Particulars of Staff 9 Information as to Water Resources 11 Land Drainage ... 13 Fisheries ... ... ... ........................................................ 21 Prevention of River Pollution 37 General Information 40 Information about Expenditure and Income ... 43 PART I GENERAL Chairman of the Board : Major EDWIN THOMPSON, O.B.E., F.L.A.S. Vice-Chairman : Major CHARLES SPENCER RICHARD GRAHAM. Members of the Board : (a) Appointed by the Minister of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food and by the Minister of Housing and Local Government. Wilfrid Hubert Wace Roberts, Esq., J.P. Desoglin, West Hall, Brampton, Cumb. -

Jubilee Digest Briefing Note for Cartmel and Furness

Furness Peninsula Department of History, Lancaster University Victoria County History: Cumbria Project ‘Jubilee Digests’ Briefing Note for Furness Peninsula In celebration of the Diamond Jubilee in 2012, the Queen has decided to re-dedicate the VCH. To mark this occasion, we aim to have produced a set of historical data for every community in Cumbria by the end of 2012. These summaries, which we are calling ‘Jubilee Digests’, will be posted on the Cumbria County History Trust’s website where they will form an important resource as a quick reference guide for all interested in the county’s history. We hope that all VCH volunteers will wish to get involved and to contribute to this. What we need volunteers to do is gather a set of historical facts for each of the places for which separate VCH articles will eventually be written: that’s around 315 parishes/townships in Cumberland and Westmorland, a further 30 in Furness and Cartmel, together with three more for Sedbergh, Garsdale and Dent. The data included in the digests, which will be essential to writing future VCH parish/township articles, will be gathered from a limited set of specified sources. In this way, the Digests will build on the substantial progress volunteers have already made during 2011 in gathering specific information about institutions in parishes and townships throughout Cumberland and Westmorland. As with all VCH work, high standards of accuracy and systematic research are vital. Each ‘Jubilee Digest’ will contain the following and will cover a community’s history from the earliest times to the present day: Name of place: status (i.e. -

The Crucifixion: Stainer's Invention of the Anglican Passion

The Crucifixion: Stainer’s Invention of the Anglican Passion and Its Subsequent Influence on Descendent Works by Maunder, Somervell, Wood, and Thiman Matthew Hoch Abstract The Anglican Passion is a largely forgotten genre that flourished in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Modeled distinctly after the Lutheran Passion— particularly in its use of congregational hymns that punctuate and comment upon the drama—Anglican Passions also owe much to the rise of hymnody and small parish music-making in England during the latter part of the nineteenth century. John Stainer’s The Crucifixion (1887) is a quintessential example of the genre and the Anglican Passion that is most often performed and recorded. This article traces the origins of the genre and explores lesser-known early twentieth-century Anglican Passions that are direct descendants of Stainer’s work. Four works in particular will be reviewed within this historical context: John Henry Maunder’s Olivet to Calvary (1904), Arthur Somervell’s The Passion of Christ (1914), Charles Wood’s The Passion of Our Lord according to St Mark (1920), and Eric Thiman’s The Last Supper (1930). Examining these works in a sequential order reveals a distinct evolution and decline of the genre over the course of these decades, with Wood’s masterpiece standing as the towering achievement of the Anglican Passion genre in the immediate aftermath of World War I. The article concludes with a call for reappraisal of these underperformed works and their potential use in modern liturgical worship. A Brief History of the Passion Genre from the sung in plainchant, and this practice continued Medieval Era to the Eighteenth Century through the late medieval and early Renaissance eras. -

Beckgate Farmhouse £575,000

BECKGATE FARMHOUSE £575,000 Barbon, The Yorkshire Dales, LA6 2LT The quintessential country cottage. Incredibly charismatic and in an enviable village setting, this is an absolute ‘gem’. This delightful cottage is newly renovated in a gentle and sympathetic manner with great respect for the architectural features and history of this period property. A three storey home has been created offering four bedrooms and three reception rooms. Set within large established gardens of 0.30 acres (0.12 hectares) and enjoying lovely views of Barbon Fell with great parking provision - all in all, it’s a great place to embrace village life in this sought after Lune Valley village. A must see! www.davis-bowring.co.uk Welcome to BECKGATE FARMHOUSE £575,000 Barbon, The Yorkshire Dales, LA6 2LT There's no doubt about it, this is an utterly charming and beguiling country cottage. Offering well proportioned living space, period character features and a cracking village location. We’re hard pressed to choose our favourite thing, so here’s our (not so) short list for you to mull over… • For starters, this is indeed a rare opportunity - on the open market for the first time in over 60 years, the current owners bought the house privately last year and have carried out an extensive and truly sympathetic renovation programme (this included a new roof, a new heating and plumbing system, complete rewiring, newly plastered walls and ceilings amongst other things). They consciously introduced reclaimed materials as opposed to buying ‘new’ to enhance the period charm (the wooden kitchen floor, slate worktops and earthenware sink are great examples of this) and overhauled other elements (such as the sash windows, oak beams and lintels, oak and pine boarded doors) rather than imposing new on the structure. -

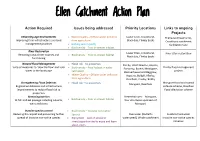

Ellen Catchment Action Plan

Ellen Catchment Action Plan Action Required Issues being addressed Priority Locations Links to ongoing Projects Enhancing Agri-Environments • Water Quality – Diffuse water pollution Lower Ellen, Crookhurst, Ellenwise (Crookhurst), Improving farm infrastructure and land from agriculture Black dub, Flimby becks Crookhurst catchment management practices • Bathing water quality facilitation fund • Biodiversity – Poor in-stream habitat River Restoration Lower Ellen, Crookhurst, River Ellen restoration Restoring natural river courses and • Biodiversity – Poor in-stream habitat Black dub, Flimby becks functioning Natural Flood Management • Flood risk – to properties Flimby, West Newton, Hayton, Suite of measures to ‘slow the flow’ and hold Flimby flood management • Biodiversity – Poor habitat in wider Parsonby, Bothel, Mealsgate, water in the landscape project catchment Blennerhasset and Baggrow, • Water Quality – Diffuse water pollution Aspatria, Bullgill, Allerby, from agriculture Dearham, Crosby, Birkby Strengthening Flood Defences • Flood risk – to properties Maryport flood and coastal Maryport, Dearham Engineered defences and infrastructure defence scheme, Dearham improvements to reduce flood risk to flood alleviation scheme properties Removing barriers Netherhall weir – Maryport, to fish and eel passage including culverts, • Biodiversity – Poor in-stream habitat four structures upstream of weirs and dams Maryport Invasive species control • Biodiversity – Invasive non-native Reducing the impact and preventing further species Overwater (Nuttall’s -

Directory to Western Printed Heritage Collections

Directory to western printed heritage collections A. Background to the collections B. Major named Collections of rare books C. Surveys of Early and Rare Books by Place of Origin D. Surveys of Special Collections by Format A. Background to the Collections A1. Introduction. The Library was founded in 1973 (British Library Act 1972). A number of existing collections were transferred into its care at that time, the most extensive of which were those of the British Museum’s Department of Printed Books (including the National Reference Library of Science and Invention), Department of Mss, and Department Oriental Mss and Printed Books. Other collections of rare and special materials have been added subsequently, most notably the India Office Library & Records in 1982. The Library today holds over 150 million collection items, including books, pamphlets, periodicals, newspapers, printed music, maps, mss, archival records, sound recordings, postage stamps, electronic titles, and archived websites; this figure includes an estimated 4.1 million books, pamphlets and periodical titles printed in the West from the 15th cent to the 19th cent. The breadth of collecting in terms of subjects, dates, languages, and geographical provenance has always been a feature of collection building policies. A wide range of heritage materials continues to be acquired from Britain and overseas through purchase and donation. The Library’s early printed materials feature prominently in a range of digital facsimile products, e.g. Early English Books Online, Eighteenth Century Collections Online, Early Music Online, Nineteenth Century Collections Online, and Google Books. Direct links to facsimiles are increasingly provided from the Library’s website, particularly from the main catalogues.