Special Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download PDF Booklet

“I am one of the last of a small tribe of troubadours who still believe that life is a beautiful and exciting journey with a purpose and grace well worth singing about.” E Y Harburg Purpose + Grace started as a list of songs and a list of possible guests. It is a wide mixture of material, from a traditional song I first heard 50 years ago, other songs that have been with me for decades, waiting to be arranged, to new original songs. You stand in a long line when you perform songs like this, you honour the ancestors, but hopefully the songs become, if only briefly your own, or a part of you. To call on my friends and peers to make this recording has been a great pleasure. Turning the two lists into a coherent whole was joyous. On previous recordings I’ve invited guest musicians to play their instruments, here, I asked singers for their unique contributions to these songs. Accompanying song has always been my favourite occupation, so it made perfect sense to have vocal and instrumental collaborations. In 1976 I had just released my first album and had been picked up by a heavy, old school music business manager whose avowed intent was to make me a star. I was not averse to the concept, and went straight from small folk clubs to opening shows for Steeleye Span at the biggest halls in the country. Early the next year June Tabor asked me if I would accompany her on tour. I was ecstatic and duly reported to my manager, who told me I was a star and didn’t play for other people. -

N , 1668. Concluded from Page

n , 1668. Concluded from page East Townes belonging to Names of some prsons belonging to each Ryding Meetings, Meetings. Meeting. Barniston^0 Geo : Hartas, Thomas Thom Vlram Skipson^1 son, John Watson, Thomas Beeforth Pearson, Thomas Nayler, Bonwick Peeter Settle. Harpham Lane: Mensen,Char: Cannabye, Grainsmire Joseph Helmsley, Willm Kelke Foston Botterill, Silvester Starman, Brigham Willm Ogle, Thomas Drape, Fradingham John Sugden, Christ: Oliver. Kellam Greg : Milner, Rich : Purs- H Skeene gloue, Rich: Towse, James cr Nafforton Cannabye, Robert Milner, Cottam South Burne Geo: Thomson, Tho: Cn Garton Jenkinson, Tho: Nichollson, Emswell Christopher Towse, Bryan Langtofft Robinson, Willm Gerrard. OfQ C/3 Rob: Prudam, Fr: Storye, O Zach : Smales, Tho: Ander- D The Key Benton*2 son, Henry Gerrard, Will Bridling Stringr, Thomas England, ton Carnabye Hunmanbye Ral: Stephenson, Frances *<*r Simson, Rob: Lamplough, Hastrope Anth: Gerrard, Rob: Simson. 3' On page 76 occurs the name of Josias Blenkhorne, of Whitby Meeting. The following is copied from the Yorkshire Registers and illustrates the tragedies in the life of the past, which often underlie the cold formality of the register-books. DATE NAMK. OF DEATH. RESIDENCE. DESCRIPTION. MO. MO. Blenkar ne, Joseph 1672.6.26 Whitby (died at). Son of Josias and Pickering. Elizab. perished in the sea. Blenckarne Josias 1672.7.28 Of Whitby Meeting. Perished in the sea. Pickering. Blenckarne,Christo. 1672.7.28 Of Whitby Meeting. Perished in the sea. Pickering. Blenckarne,Robert (Date of Burial, 1672.8.15). Son of Josias and Pickering. Elizab. idi 102 MEETINGS IN YORKSHIRE, 1668. Names of some prsons belonging to each I3*1. -

CIM's First Artistic Director Was Ernest Bloch, a Swiss Composer and Teacher Who Came to Cleveland from New York City

BLOCH, ERNEST (24 July 1880-15 July 1959), was an internationally known composer, conductor, and teacher recruited to found and direct the CLEVELAND INSTITUTE OF MUSIC in 1920. Bloch was born in Geneva, Switzerland. The son of Sophie (Brunschwig) and Maurice (Meyer) Bloch, a Jewish merchant, Bloch showed musical talent early and determined that he would become a composer. His teen years were marked by important study with violin and composition masters in various European cities. Between 1904 and 1916, he juggled business responsibilities with composing and conducting. In 1916 Bloch accepted a job as conductor for dancer Maud Allen's American tour. The tour collapsed after 6 weeks, but performances of his works in New York and Boston led to teaching positions in New York City. During the Cleveland years (1920-25), Bloch completed 21 works, among them the popular Concerto Grosso, which was composed for the students' orchestra at the Cleveland Institute of Music. His contributions included an institute chorus at the CLEVELAND MUSEUM OF ART, attention to pedagogy especially in composition and theory, and a concern that every student should have a direct and high-quality aesthetic experience. He taught several classes himself. After disagreements with Cleveland Institute of Music policymakers, he moved to the directorship of the San Francisco Conservatory. Following some years studying in Europe, Bloch returned to the U.S. in 1939 to teach at the Univ. of Calif.-Berkeley. He retired in 1941. His students over the years included composers Roger Sessions and HERBERT ELWELL. Bloch composed over 100 works for a variety of individual instruments and ensemble sizes and won over a dozen prestigious awards. -

Off the Beaten Track

Off the Beaten Track To have your recording considered for review in Sing Out!, please submit two copies (one for one of our reviewers and one for in- house editorial work, song selection for the magazine and eventual inclusion in the Sing Out! Resource Center). All recordings received are included in “Publication Noted” (which follows “Off the Beaten Track”). Send two copies of your recording, and the appropriate background material, to Sing Out!, P.O. Box 5460 (for shipping: 512 E. Fourth St.), Bethlehem, PA 18015, Attention “Off The Beaten Track.” Sincere thanks to this issue’s panel of musical experts: Richard Dorsett, Tom Druckenmiller, Mark Greenberg, Victor K. Heyman, Stephanie P. Ledgin, John Lupton, Angela Page, Mike Regenstreif, Seth Rogovoy, Ken Roseman, Peter Spencer, Michael Tearson, Theodoros Toskos, Rich Warren, Matt Watroba, Rob Weir and Sule Greg Wilson. that led to a career traveling across coun- the two keyboard instruments. How I try as “The Singing Troubadour.” He per- would have loved to hear some of the more formed in a variety of settings with a rep- unusual groupings of instruments as pic- ertoire that ranged from opera to traditional tured in the notes. The sound of saxo- songs. He also began an investigation of phones, trumpets, violins and cellos must the music of various utopian societies in have been glorious! The singing is strong America. and sincere with nary a hint of sophistica- With his investigation of the music of tion, as of course it should be, as the Shak- VARIOUS the Shakers he found a sect which both ers were hardly ostentatious. -

Newsletter 59

SQUIRE: BRIAN TASKER 6 ROOPERS, SPELDHURST, TUNBRIDGE WELLS, KENT, TN3 0QL TEL: 01892 862301 E-mail: [email protected] BAGMAN: CHARLIE CORCORAN 70, GREENGATE LANE, BIRSTALL, LEICESTER, LEICS LE4 3DL TEL: 01162 675654 E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] TREASURER: STEVE ADAMSON BFB 12, FLOCKTON ROAD, EAST BOWLING, BRADFORD, WEST YORKSHIRE BD4 7RH TEL: 01274 773830 E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] The Newsletter No.59 December 2008 The highlights of this Newsletter are: Page Massed Dances and their music 2 Annual Representatives’ Meeting 3 Information about Chris Harris’ “Kemps Jig” 4 ARM Agenda (and advance request for Reports) 6 Joint Morris Organisations: Nottingham Revels 28th March 2009 8 EFDSS News 8 Francis Shergold (1919-2008) A Tribute by Paul Reece 10 Cultural Olympiad 11 2009 Meetings of Morris Ring 11 Treasurer’s ramblings 11 Who’s going to which meeting? 12 Saddleworth Rushcart 2009 12 Jigs Instructional 2009 13 2009 Rapper and Longsword Tournaments 13 Redcar Sword Dancers triumphant again 14 Morris in the Media – Marks for trying? 14 Future Dates 16 Application Forms: Jigs Instructional 19 Morris Ring Meetings 20 Morris Ring Newsletter No 59 December 2008 Page 1 of 20 THE MORRIS RING IS THE NATONAL ASSOCIATION OF MEN’S MORRIS & SWORD DANCE CLUBS Music for Massed Dancing. Following the article in Newsletter No. 58 Harry Winstone, of Kemp's Men, contacted Brian Tasker, Squire of the Morris Ring, and suggested that we need to provide some indication of the tunes to be used. His comment was “50 musicians all playing their own versions. -

Interpretive Sign

1880 Ernest Bloch 1959 ROVEREDO GENEVA MUNICH FRANKFURT PARIS LONDON BOSTON NEW YORK CLEVELAND CHICAGO SANTA FE BERKELEY SAN FRANCISCO PORTLAND AGATE BEACH Composer Philosopher Humanist Photographer Mycophagist Beachcomber THOMAS BEECHAM CLAUDE DEBUSSY ALBERT EINSTEIN FRIDA KAHLO SERGE KOUSSEVITSKY GUSTAV MAHLER YEHUDI MENUHIN ZARA NELSOVA DIEGO RIVERA LEOPOLD STOKOWSKI IGOR STRAVINSKY The First American Period, comprising Unpublished Student Works (Geneva, The Second European Period New York (1916-20), Cleveland (1920-25), The Second American period, incorporating the “Agate Beach Years” (1941-59) Brussel, Frankfurt, Munich, Paris) (Switzerland, France, Italy) 1880-1903 1916-1930 San Francisco (1925-30) 1930-1938 1939-1959 Ernest Bloch was born in Geneva, Switzerland, in 1880. Although Bloch moved to New York in In his retreat at Roveredo-Capriasca, Switzerland, he immersed The Stern trust fund for Bloch was administered by the drive from here. The next day she sends a telegram. On the his parents were not particularly artistic, music called to Bloch 1916. Because success had himself in a study of Hebrew in preparation for the composition University of California at Berkeley. Upon his return from his 11th I’ll go and pick her up in Oswego. In the meantime I’ve even as a child. At the age of 9 he began learning to play the violin, eluded him in Europe, he of his Sacred Service (Avodath Hakodesh), which had its debut eight year sabbatical, Bloch was to occupy an endowed chair at discovered a really nice path, flat, which among wild forests quickly proving himself to be a prodigy. By the age of 11, he vowed took a job as the orchestral in Turin, Italy, in 1934, followed the university in fulfillment of the terms surrounding the Stern leads to another beach, huge, empty, on the other side of a to become a composer and then ritualistically burned the written director for a new modern- by performances in Naples, fund. -

Sound Recording in the British Folk Revival: Ideology, Discourse and Practice, 1950–1975

Sound recording in the British folk revival: ideology, discourse and practice, 1950–1975 Matthew Ord Submitted in fulfilment of the degree of PhD International Centre for Music Studies Newcastle University March 2017 Abstract Although recent work in record production studies has advanced scholarly understandings of the contribution of sound recording to musical and social meaning, folk revival scholarship in Britain has yet to benefit from these insights. The revival’s recording practice took in a range of approaches and contexts including radio documentary, commercial studio productions and amateur field recordings. This thesis considers how these practices were mediated by revivalist beliefs and values, how recording was represented in revivalist discourse, and how its semiotic resources were incorporated into multimodal discourses about music, technology and traditional culture. Chapters 1 and 2 consider the role of recording in revivalist constructions of traditional culture and working class communities, contrasting the documentary realism of Topic’s single-mic field recordings with the consciously avant-garde style of the BBC’s Radio Ballads. The remaining three chapters explore how the sound of recorded folk was shaped by a mutually constitutive dialogue with popular music, with recordings constructing traditional performance as an authentic social practice in opposition to an Americanised studio sound equated with commercial/technological mediation. As the discourse of progressive rock elevated recording to an art practice associated with the global counterculture, however, opportunities arose for the incorporation of rock studio techniques in the interpretation of traditional song in the hybrid genre of folk-rock. Changes in studio practice and technical experiments with the semiotics of recorded sound experiments form the subject of the final two chapters. -

Detailed Assessment of NO2 at South Killingholme

Local Authority Dr Matthew Barnes Officer Department Environmental Health (Commercial) Church Square House Scunthorpe Address North Lincolnshire DN15 6XQ Telephone 01724 297336 e-mail [email protected] Date January 2016 Report Status Final Report 1 Executive summary North Lincolnshire Council’s Air Quality Progress Report 2011 identified a possible exceedance of nitrogen dioxide alongside the A160 in South Killingholme. For this reason, in October 2013 North Lincolnshire Council installed an air quality monitoring site to more accurately measure nitrogen dioxide, nitric oxide and nitrogen oxides at this location. Nitric oxide (NO) is mainly derived from road transport emissions and other combustion processes. Nitric oxide is not considered to be harmful to health, however, once emitted to the atmosphere it is rapidly oxidised to nitrogen dioxide (NO2) which can be harmful to health. NO2 can irritate the lungs and lower resistance to respiratory infections. Continued exposure to concentrations above the recommended air quality objectives may cause increased incidence of acute respiratory illness in children. The main source of NO2 is from road traffic emissions. At South Killinghome the principle source is from vehicles using the A160 dual-carriage way, which provides access to the Port of Immingham, local refineries and power stations. It is also the main route to the proposed Able Marine Energy Park, a deep water quay and manufacturing facility for the offshore wind energy industry. To provide better access to the Port of Immingham and surrounding area, the Highways Agency are upgrading both the A160 and A180. It is anticipated that 1 construction will take approximately 16 months and should be completed by Autumn 2016. -

Ernest Bloch (1880-1959) Three Nocturnes (1924) Andante Andante Quieto Tempestoso

Ernest Bloch (1880-1959) Three Nocturnes (1924) Andante Andante quieto Tempestoso Bloch was born into a Jewish family in Geneva - the son of a clock-maker. He learned the violin and composition, initially in Geneva, but in his teens he moved to Brussels to study with Eugène Ysaÿe, then to Frankfurt, Munich and Paris. In his mid-twenties he returned to Geneva where he married and entered his father's firm as a bookkeeper and salesman, along with occasional musical activities – composing, conducting and lecturing. His opera Macbeth was successfully performed at the Paris Opéra-Comique in 1910. Six years later he went to the United States, initially to conduct a dance company's tour. The tour collapsed, but he secured a job teaching composition at a New York music college and his wife and children joined him there. Performances of new works including some with a Jewish flavour ( Trois poèmes juifs and Schelomo) increased his visibility. His popular association with 'Jewish' music was enhanced by G.Schirmer publishing his works with a characteristic trademark logo – the six-pointed Star of David with the initials E.B. in the centre. From 1920-5 he served as the founding director of the Cleveland Institute of Music and from 1925–30 as director of the San Francisco Conservatory of Music. The Conservatory subsidised his return to Switzerland in the 1930s allowing him to compose undisturbed. But with the rise of the Nazis and the need to maintain his American citizenship, in 1939 he returned to a chair at UC Berkeley which he held until his retirement to Agate Bay, Oregon, where he continued to compose widely, took photographs and polished agates. -

UNIVERSAL MUSIC • Rammstein – Videos 1995 – 2012 (DVD) • The

Rammstein – Videos 1995 – 2012 (DVD) The Rolling Stones – Grrr (Album Vinyl Box) Insane Clown Posse – Insane Clown Posse & Twiztid's American Psycho Tour Documentary (DVD) New Releases From Classics And Jazz Inside!! And more… UNI13-03 “Our assets on-line” UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2450 Victoria Park Ave., Suite 1, Willowdale, Ontario M2J 5H3 Phone: (416) 718.4000 Artwork shown may not be final UNIVERSAL MUSIC CANADA NEW RELEASE Artist/Title: Hollywood Undead – Notes From The Underground Bar Code: Cat. #: B001797702 Price Code: SP Order Due: December 20, 2012 Release Date: January 8, 2013 File: Hip Hop /Rock Genre Code: 34/37 Box Lot: 25 SHORT SELL CYCLE Key Tracks: We Are KEY POINTS: 14 BRAND NEW TRACKS Hollywood Undead have sold over 83,000 albums in Canada HEAVY outdoor, radio and online campaign First single “We Are” video is expected mid December 2013 Tour in the works 2.8 million Facebook friends and 166,000 Twitter followers Also Available American Tragedy (2011) ‐ B001527502 Swan Song (2008) ‐ B001133102 INTERNAL USE Label Name: Territory: Choose Release Type: Choose For additional artist information please contact JP Boucher at 416‐718‐4113 or [email protected]. UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2450 Victoria Park Avenue, Suite 1, Toronto, ON M2J 5H3 Phone: (416) 718‐4000 Fax: (416) 718‐4218 UNIVERSAL MUSIC CANADA NEW RELEASE Artist/Title: Black Veil Brides / Wretched And Divine: The Story Of Bar Code: The Wild Ones (Regular CD) Cat. #: B001781702 Price Code: SP 02537 22095 Order Due: Dec. 20, 2012 Release Date: Jan. 8, 2013 6 3 File: Rock Genre Code: 37 Box Lot: 25 Short Sell Cycle Key Tracks: Artist/Title: Black Veil Brides / Wretched And Divine: The Story Of Bar Code: The Wild Ones (Deluxe CD/DVD) Cat. -

Green Space Sites

Appendix A: Summary of Local Plan (2000) green space sites Open space provision in Local Plan, 2000, by Ward (hectares) Educational Public playing Ward Agricultural Allotment Amenity area Cemetery grounds Golf course Other Private grounds Private pitch Public park field/play area Avenue 4.76 1.06 18.38 12.82 1.74 9.75 Beverley 5.99 1.79 3.87 19.65 4.20 4.03 28.82 Boothferry 6.33 3.64 2.04 9.68 9.37 0.00 1.36 Bransholme East 152.10 1.88 17.41 18.16 9.35 15.69 Bransholme West 20.12 7.63 0.04 0.92 1.42 Bricknell 5.04 1.28 22.15 16.34 5.44 6.32 14.68 6.57 Derringham 3.08 9.49 10.01 3.37 3.75 Drypool 8.37 0.63 12.67 3.53 7.93 4.03 Holderness 4.19 1.31 14.45 15.32 1.17 48.52 14.97 Ings 27.66 10.97 12.58 47.75 7.38 6.69 10.08 Kings Park 2.42 2.01 12.29 36.41 18.15 Longhill 0.97 0.60 19.98 0.00 3.53 18.19 10.76 Marfleet 39.92 2.84 0.40 26.00 23.70 19.65 6.55 16.77 Myton 0.86 3.47 0.93 3.18 10.45 0.40 0.53 3.23 3.59 Newington 5.09 1.32 19.89 6.64 9.02 14.80 1.07 Newland 8.79 3.22 1.60 8.06 3.40 0.85 Orchard Park & Greenwood 8.33 9.99 4.83 11.36 Pickering 6.52 20.01 16.61 22.88 50.05 3.88 Southcoates East 9.14 0.73 11.50 15.85 1.10 2.35 Southcoates West 0.38 1.60 1.99 0.21 2.23 St. -

14302 76969 1 1>

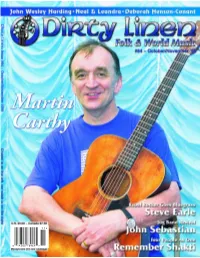

11> 0514302 76969 establishment,” he hastened to clarify. “I wish it were called the Legion of Honour, but it’s not.” Still in all, he thinks it’s good for govern- M artin C arthy ments to give cultural awards and is suitably honored by this one, which has previously gone to such outstanding folk performers as Jeannie Robertson. To decline under such circum- stances, he said, would have been “snotty.” Don’t More importantly, he conceives of his MBE as recognition he shares with the whole Call Me folk scene. “I’ve been put at the front of a very, very long queue of people who work hard to make a folk revival and a folk scene,” he said. Sir! “All those people who organized clubs for nothing and paid you out of their own pocket, and fed you and put you on the train the next morning, and put you to bed when you were drunk! What [the government is] doing, is taking notice of the fact that something’s going on for the last more than 40 years. It’s called the folk revival. They’ve ignored it for that long. And someone has suddenly taken notice, and that’s okay. A bit of profile isn’t gonna hurt us — and I say us, the plural, for the folk scene — isn’t gonna hurt us at all.” In the same year as Carthy’s moment of recognition, something happened that did hurt the folk scene. Lal Waterson, Carthy’s sister-in- law, bandmate, near neighbor and close friend, died of cancer.