Playboy Enterprises, Inc. V. Netscape Communications Corp. (9Th. Cir

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Netscape Guide by Yahoo!

Netscape Guide By Yahoo! Now Available New Customizable Internet Information and Navigation Service Launched by Netscape and Yahoo! SANTA CLARA, CA and MOUNTAIN VIEW, CA -- April 29, 1997 -- Yahoo! Inc. (NASDAQ: YHOO) and Netscape Communications Corporation (NASDAQ: NSCP) today launched Netscape Guide by Yahoo!, a new personalized Internet navigation service designed to provide Internet users with a central source of sites, news and events on the Web. The Guide features customizable sections for several popular information categories, including Business, Finance, Entertainment, Sports, Computers & Internet, Shopping and Travel. Yahoo! plans to expand the service with additional categories in the future, including local information. Netscape Guide by Yahoo! replaces the Destinations section of the Netscape Internet Site and is immediately accessible through Netscape's Internet site (http://home.netscape.com), from the "Guide" button on the Netscape Communicator toolbar and from the "Destinations" button on Netscape Navigator 3.0. Users accessing Destinations will be automatically directed to Netscape Guide by Yahoo!. "Netscape Guide by Yahoo! gives Internet users quick and easy access to the most popular information areas on the Web, all from one central location," said Jeff Mallett, Yahoo!'s senior vice president of business operations. "It also provides Web content providers and advertisers a unique opportunity to reach targeted and growing audiences." "Accessible to the more than four million daily visitors to the Netscape Internet site and the over 50 million users of Netscape client software, Netscape Guide by Yahoo! will direct users to the online sites, news and information they need," said Jennifer Bailey, vice president of electronic marketing at Netscape. -

IE 5.5 and Netscape 4.75 - Why Upgrade? ..Page 1

In This Issue . IE 5.5 and Netscape 4.75 - Why Upgrade? ..page 1 WindowsME for Home Computing ..…..…..page 1 Critical Updates are Essential ……..……….page 1 Win 95/98 Web Browser Upgrade.…………page 2 Permanent LRC Stations…………...……….page 2 cc:Mail is Retiring ……..…………..………..page 2 The newsletter for IPFW computer users Information Technology Services October 2000 Courses & Resources…………….……….….page 2 IE 5.5 and Netscape for Home 4.75 - Why Upgrade? Computing Campus surfers should update their browsers to the Microsoft recently released its upgrade to Windows 98 latest versions of Netscape and Internet Explorer (IE). for home computing — Windows Millennium (WindowsMe). Windows users may do so by the following instructions on Follett's IPFW Bookstore is now offering the CD to students, page 2. Macintosh users may obtain the instructions for faculty, and staff as part of IU's licensing agreement with creating an alias for either or both programs from the Help Microsoft. Is the upgrade for you? Windows Millennium Desk (e-mail: [email protected]). includes: Very basic digital media editing tools Why upgrade? In general, obtaining the latest 4 IE 5.5 (also downloadable for Windows 98) version of your favorite browser helps ensure that you have 4 4 Media Player 7 (also downloadable for Windows 98) the most capable and secure browser for today's Web If you have no compelling need for the above features environment. Specifically, the newest and most significant or if you take the time to do wnload IE 5.5 and/or Media Player 7 features of each include: for Windows 98, you may want to skip this upgrade. -

Netscape 6.2.3 Software for Solaris Operating Environment

What’s New in Netscape 6.2 Netscape 6.2 builds on the successful release of Netscape 6.1 and allows you to do more online with power, efficiency and safety. New is this release are: Support for the latest operating systems ¨ BETTER INTEGRATION WITH WINDOWS XP q Netscape 6.2 is now only one click away within the Windows XP Start menu if you choose Netscape as your default browser and mail applications. Also, you can view the number of incoming email messages you have from your Windows XP login screen. ¨ FULL SUPPORT FOR MACINTOSH OS X Other enhancements Netscape 6.2 offers a more seamless experience between Netscape Mail and other applications on the Windows platform. For example, you can now easily send documents from within Microsoft Word, Excel or Power Point without leaving that application. Simply choose File, “Send To” to invoke the Netscape Mail client to send the document. What follows is a more comprehensive list of the enhancements delivered in Netscape 6.1 CONFIDENTIAL UNTIL AUGUST 8, 2001 Netscape 6.1 Highlights PR Contact: Catherine Corre – (650) 937-4046 CONFIDENTIAL UNTIL AUGUST 8, 2001 Netscape Communications Corporation ("Netscape") and its licensors retain all ownership rights to this document (the "Document"). Use of the Document is governed by applicable copyright law. Netscape may revise this Document from time to time without notice. THIS DOCUMENT IS PROVIDED "AS IS" WITHOUT WARRANTY OF ANY KIND. IN NO EVENT SHALL NETSCAPE BE LIABLE FOR INDIRECT, SPECIAL, INCIDENTAL, OR CONSEQUENTIAL DAMAGES OF ANY KIND ARISING FROM ANY ERROR IN THIS DOCUMENT, INCLUDING WITHOUT LIMITATION ANY LOSS OR INTERRUPTION OF BUSINESS, PROFITS, USE OR DATA. -

10 Forces That Flattened the World Berlin Wall Falling Netscape Goes

Berlin Wall Falling 10 Forces That Flattened the • 11/9/89=9/11/89….Their 9/11. • Capitalism wins vs. Communism. World • More economies governed from the ground up. • Unlocked the potential of countries like India, Brazil, China, and Soviet Empire. Netscape Goes Public Work Flow Software • P.C. had given everybody the ability to • Not as celebrated as other flatteners. create, but not share. • No specific date….Mid 1990’s. • Netscape allowed emergence of low- • Enabled people in more places to cost global connectivity. design, display, manage and • Commercial web browser that could collaborate on business data. retrieve websites. • Netscape combined mac and p.c. into • Anything that is digitized can be shared format usable for all. and collaborated on. 1 Outsourcing Uploading • India always had intelligence, but used to have to leave India to find jobs…”Brain Drain”. • “Open Source” community. • Y2K computer crisis. Needed software • Software that is available to everybody, engineers. can be uploaded by everybody. • Any individual who has something to • Combination of PC, internet, fiber-optic cable contribute can improve it. made an unlimited potential for collaboration. • Bunch of geeks creating better software • Any service, call center, business support for free. operation or knowledge work that could be • Blogs or Wikipedia. digitized could be sourced globally to the cheapest, smartest and most efficient. Offshoring Supply-Chaining • Not outsourcing. • A method of collaborating horizontally among • When a company takes one of its factories that suppliers, retailers, and consumers to create is operating in Canton, Ohio, and moves the value. whole factory offshore to Canton, China. -

Turning Off Pop-Up Blockers

Turning Off Pop-Up Blockers See the following instructions for how to turn off your pop-up blockers. We have included instructions for Internet Explorer 7, Internet Explorer 8, Internet Explorer 9, Google, Yahoo, SBC Yahoo, Firefox, Safari, and Netscape. If you are using another browser, please email [email protected]. Open Internet Explorer Click on Tools menu Select Pop-up Blocker Select Turn Off Pop-up Blocker To turn the Pop-Up Blocker back on, you can go back in and recheck the entry to re-enable their Pop- Up Blocker. 1 Updated 04/29/2011 JRH Open Internet Explorer Click on Tools menu Select Internet Options Click on the Privacy tab Uncheck Turn On Pop-up Blocker Click OK To turn the Pop-Up Blocker back on, you can go back in and recheck the entry to re-enable their Pop- Up Blocker. 2 Open Internet Explorer. Open the Tools Menu (press ALT T). Click on Pop-up Blocker > Turn off Pop-up Blocker To turn the Pop-Up Blocker back on, you can go back into the Tools menu and click Pop-up Blocker > Turn on Pop-up Blocker. 3 The following icon is the Pop-Up Blocker: To allow pop-ups to appear, merely click on the icon. You should now see the following: To turn the Pop-Up Blocker back on, you can click the icon again to re-enable the pop-up blocker. Note: if this is not sufficient to allow pop-up windows to appear, you may need to disable the Google toolbar completely by following the approach below. -

World Wide Web Distributed Authoring and Versioning (WEBDAV): an Introduction1

World Wide Web Distributed Authoring and Versioning (WEBDAV): An Introduction1 E. James Whitehead, Jr. Dept. of Information and Computer Science University of California, Irvine Irvine, CA 92697-3425 Email: [email protected] Phone: (714) 824-4121 Fax: (714) 824-1715 1.0 Introduction Today the typical use of the World Wide Web is to browse information in a largely read- only manner. However, this was not the original conception of the Web; as early as 1990, a prototype Web editor and browser was operational on the Next platform, demonstrating how Web content could be read and written. Unfortunately, most of the world never saw this editor/browser, instead developing their view of the Web from the widely distributed text-based line mode browser. When NCSA Mosaic was developed, it improved the line mode browser by adding a graphical user interface and inline images, but had no provision for editing. As Mosaic 2.4 reached critical mass in 1993-4, “publish/browse” became the dominant model for the Web. However, the original view of the Web as a readable and writable collaborative medium was not lost. In 1995 two browser/editor products were released: NaviPress by NaviSoft and FrontPage by Vermeer. These products began developing a market for authoring tools which allow a user to edit HyperText Markup Language (HTML) [Ragg97] pages remotely, taking advantage of the ability to work at a distance over the Internet. In early 1996, NaviSoft and Vermeer were purchased by America Online and Microsoft respec- tively, presaging major corporate interest in Web distributed authoring technology. -

Peer Participation and Software

Peer Participation and Software This report was made possible by the grants from the John D. and Cath- erine T. MacArthur Foundation in connection with its grant-making initiative on Digital Media and Learning. For more information on the initiative visit www.macfound.org. The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Reports on Digital Media and Learning Peer Participation and Software: What Mozilla Has to Teach Government by David R. Booth The Future of Learning Institutions in a Digital Age by Cathy N. Davidson and David Theo Goldberg with the assistance of Zoë Marie Jones The Future of Thinking: Learning Institutions in a Digital Age by Cathy N. Davidson and David Theo Goldberg with the assistance of Zoë Marie Jones New Digital Media and Learning as an Emerging Area and “Worked Examples” as One Way Forward by James Paul Gee Living and Learning with New Media: Summary of Findings from the Digital Youth Project by Mizuko Ito, Heather Horst, Matteo Bittanti, danah boyd, Becky Herr-Stephenson, Patricia G. Lange, C. J. Pascoe, and Laura Robinson with Sonja Baumer, Rachel Cody, Dilan Mahendran, Katynka Z. Martínez, Dan Perkel, Christo Sims, and Lisa Tripp Young People, Ethics, and the New Digital Media: A Synthesis from the GoodPlay Project by Carrie James with Katie Davis, Andrea Flores, John M. Francis, Lindsay Pettingill, Margaret Rundle, and Howard Gardner Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21st Century by Henry Jenkins (P.I.) with Ravi Purushotma, Margaret Weigel, Katie Clinton, and Alice J. Robison The Civic Potential of Video Games by Joseph Kahne, Ellen Middaugh, and Chris Evans Peer Production and Software What Mozilla Has to Teach Government David R. -

TAP Into Learning, Fall-Winter 2000. INSTITUTION Stanford Univ., CA

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 456 797 IR 020 546 AUTHOR Burns, Mary; Dimock, Vicki; Martinez, Danny TITLE TAP into Learning, Fall-Winter 2000. INSTITUTION Stanford Univ., CA. ERIC Clearinghouse on Educational Media and Technology. SPONS AGENCY Office of Educational Research and Improvement (ED), Washington, DC. PUB DATE 2000-00-00 NOTE 26p.; Winter 2000 is the final issue of "TAP into Learning CONTRACT RJ9600681 AVAILABLE FROM For full text: http://www.sedl.org/tap/newsletters/. PUB TYPE Collected Works Serials (022) JOURNAL CIT TAP into Learning; v2 n3, v3 n1-2 Fall-Win 2000 EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Computer Assisted Instruction; Computer Software; *Computer Uses in Education; Constructivism (Learning); Educational Technology; Elementary Secondary Education; *Hypermedia; Interactive Video; Learning; Learning Activities; Multimedia Instruction; *Multimedia Materials; Visual Aids IDENTIFIERS Reflective Inquiry; Technology Role ABSTRACT This document consists of the final three issues of "TAP into Learning" (Technology Assistance Program) .The double fall issue focuses on knowledge construction and on using multimedia applications in the classroom. Contents include: "Knowledge Under Construction"; "Hegel and the Dialectic"; "Implications for Teaching and Learning"; "How Can Technology Help in the Developmental Process?"; "Type I and Type II Applications"; "Children's Ways of Learning and the Evolution of the Personal Computer"; "Classroom Example: Trial of Julius Caesar's Murderers and Court Case Website"; "Glossary of World Wide Web Terms"; "Hypermedia: What Do I Need To Use Thought Processing Software?"; and "What Do I Need To Make a Web Page in My Class?" The winter issue, "Learning as an Active and Reflective Process," focuses on the process of learning and on using video in the classroom. -

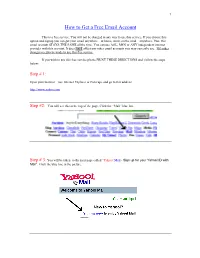

How to Get a Free Email Account

1 How to Get a Free Email Account This is a free service. You will not be charged in any way to use this service. If you choose this option and signup you can get your email anywhere – at home, work, on the road – anywhere. Plus, this email account STAYS THE SAME all the time. You can use AOL, MSN or ANY independent internet provider with this account. It does NOT affect any other email accounts you may currently use. NO other changes need to be made to use this free service. If you wish to use this free service please PRINT THESE DIRECTIONS and follow the steps below: Step # 1: Open your browser – use Internet Explorer or Netscape and go to this address: http://www.yahoo.com Step #2: You will see this at the top of the page. Click the “Mail” blue line. Step # 3: You will be taken to the next page called “Yahoo! Mail - Sign up for your Yahoo! ID with Mail”. Click the blue line in the picture. 2 Step # 4: You will be asked to fill in some questions for Yahoo!. They are shown below: This is the first section of the page. The “Yahoo! ID” will be PART of your new email address. Since so many people use this free service please choose a long Yahoo! ID with a couple of numbers in the address. The “Password” is used to retrieve email messages you may receive. This is important – do not forget this password! The “Re-type Password” box is for verification only. -

Marc Andreessen on Why Software Is Eating the World

Why Software Is Eating The World By MARC ANDREESSEN This week, Hewlett-Packard (where I am on the board) announced that it is exploring jettisoning its struggling PC business in favor of investing more heavily in software, where it sees better potential for growth. Meanwhile, Google plans to buy up the cell- phone handset maker Motorola Mobility. Both moves surprised the tech world. But both moves are also in line with a trend I've observed, one that makes me optimistic about the future growth of the American and world economies, despite the recent tur- moil in the stock market. In short, software is eating the world. More than 10 years after the peak of the 1990s dot-com bubble, a dozen or so new Inter- net companies like Facebook and Twitter are sparking controversy in Silicon Valley, due to their rapidly growing private market valuations, and even the occasional successful IPO. With scars from the heyday of Webvan and Pets.com still fresh in the investor psy- che, people are asking, "Isn't this just a dangerous new bubble?" I, along with others, have been arguing the other side of the case. (I am co-founder and general partner of venture capital firm Andreessen-Horowitz, which has invested in Facebook, Groupon, Skype, Twitter, Zynga, and Foursquare, among others. I am also personally an investor in LinkedIn.) We believe that many of the prominent new Inter- net companies are building real, high-growth, high-margin, highly defensible business- es. Today's stock market actually hates technology, as shown by all-time low price/earn- ings ratios for major public technology companies. -

User's Guide to Aolpress

User’s Guide to AOLpress 2.0 Do-it-Yourself Publishing for the Web 1997 America Online, Inc. AOL20-040797 Information in this document is subject to change without notice. Both real and fictitious companies, names, addresses, and data are used in examples herein. No part of this document may be reproduced without express written permission of America Online, Inc. 1997 America Online, Inc. All rights reserved. America Online is a registered trademark and AOLpress, AOLserver, PrimeHost, AOL, the AOL triangle logo, My Place, Netizens, and WebCrawler are trademarks of America Online, Inc. GNN is a registered trademark, and Global Network Navigator, GNNpress, and GNNserver are trademarks of Global Network Navigator, Inc. MiniWeb, NaviLink, NaviPress, NaviServer, and NaviService are trademarks of NaviSoft, Inc. Illustra is a trademark of Illustra Information Technologies, Inc. All other brand or product names are trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective companies or organizations. Author: Yvonne DeGraw Cover Art and Illustrations: Amy Luwis Special Thanks To: Thomas Storm, Cathe Gordon, Angela Howard, George W. Williams, V, Dave Long, Dave Bourgeois, Joel Thames, Natalee Press-Schaefer, Robin Balston, Linda T. Dozier, Jeff Dozier, Doug McKee, and Jeff Rawlings. Quick Table of Contents Contents Part 1: Getting Started Welcome! 11 Chapter 1 Installing AOLpress 17 Chapter 2 Create a Web Page in 10 Easy Steps 21 Chapter 3 Browsing with AOLpress 33 Part 2: Creating Pages Chapter 4 Web Pages and What to Put in Them 45 Chapter 5 Creating -

Web Browsers

WEB BROWSERS Page 1 INTRODUCTION • A Web browser acts as an interface between the user and Web server • Software application that resides on a computer and is used to locate and display Web pages. • Web user access information from web servers, through a client program called browser. • A web browser is a software application for retrieving, presenting, and traversing information resources on the World Wide Web Page 2 FEATURES • All major web browsers allow the user to open multiple information resources at the same time, either in different browser windows or in different tabs of the same window • A refresh and stop buttons for refreshing and stopping the loading of current documents • Home button that gets you to your home page • Major browsers also include pop-up blockers to prevent unwanted windows from "popping up" without the user's consent Page 3 COMPONENTS OF WEB BROWSER 1. User Interface • this includes the address bar, back/forward button , bookmarking menu etc 1. Rendering Engine • Rendering, that is display of the requested contents on the browser screen. • By default the rendering engine can display HTML and XML documents and images Page 4 HISTROY • The history of the Web browser dates back in to the late 1980s, when a variety of technologies laid the foundation for the first Web browser, WorldWideWeb, by Tim Berners-Lee in 1991. • Microsoft responded with its browser Internet Explorer in 1995 initiating the industry's first browser war • Opera first appeared in 1996; although it have only 2% browser usage share as of April 2010, it has a substantial share of the fast-growing mobile phone Web browser market, being preinstalled on over 40 million phones.