The Rhetoric of the Dalai Lama

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Honolulu Star-Advertiser

B CITY EDITOR: David Butts / [email protected] / 529-4310 WEDNESDAY 10/7/20 VANDALS AT WORK A $20,000 digital sign is damaged at Makapu‘u Lighthouse Trail over the weekend >> B2 ——— BIG Q >> B2 COMICS & PUZZLES >> B7-9 KOKUA LINE CHRISTINE DONNELLY Must apply for extended jobless benefits uestion: Are the extended benefits Q automatic once I run out of unemploy- ment? It’s getting close. What do I do? Answer: No, Pan- demic Emergency Unem- ployment Compensation is not automatic. You have to apply for this pro- gram, which adds 13 weeks of benefits for eligi- UCLA VIA AP / 2015 ble claimants, and you must have a zero balance Andrea Ghez, professor of physics and astronomy at UCLA, was one of three scientists who was awarded this year’s Nobel Prize in in your Unemployment In- physics for advancing the understanding of black holes. Ghez was photographed on the university’s campus. surance account before you do so, according to the state Department of Labor and Industrial Rela- Nobel winner is Keck Observatory user tions. You would apply through your online UI ac- Astronomer Andrea Ghez has been studying the ry’s telescopes, Lewis said count and answer a series Ghez probably uses them of questions to determine Galactic Center from Hawaii island since 1995 more often than anyone whether you are eligible. else — about a dozen nights For instructions on how Star-Advertiser staff covering a supermassive per year. to apply, see labor.hawaii. and news services black hole at the center of The observatory’s twin gov/ui/. -

The Nobel Peace Prize

TITLE: Learning From Peace Makers OVERVIEW: Students examine The Dalai Lama as a Nobel Laureate and compare / contrast his contributions to the world with the contributions of other Nobel Laureates. SUBJECT AREA / GRADE LEVEL: Civics and Government 7 / 12 STATE CONTENT STANDARDS / BENCHMARKS: -Identify, research, and clarify an event, issue, problem or phenomenon of significance to society. -Gather, use, and evaluate researched information to support analysis and conclusions. OBJECTIVES: The student will demonstrate the ability to... -know and understand The Dalai Lama as an advocate for peace. -research and report the contributions of others who are recognized as advocates for peace, such as those attending the Peace Conference in Portland: Aldolfo Perez Esquivel, Robert Musil, William Schulz, Betty Williams, and Helen Caldicott. -compare and contrast the contributions of several Nobel Laureates with The Dalai Lama. MATERIALS: -Copies of biographical statements of The Dalai Lama. -List of Nobel Peace Prize winners. -Copy of The Dalai Lama's acceptance speech for the Nobel Peace Prize. -Bulletin board for display. PRESENTATION STEPS: 1) Students read one of the brief biographies of The Dalai Lama, including his Five Point Plan for Peace in Tibet, and his acceptance speech for receiving the Nobel Prize for Peace. 2) Follow with a class discussion regarding the biography and / or the text of the acceptance speech. 3) Distribute and examine the list of Nobel Peace Prize winners. 4) Individually, or in cooperative groups, select one of the Nobel Laureates (give special consideration to those coming to the Portland Peace Conference). Research and prepare to report to the class who the person was and why he / she / they won the Nobel Prize. -

Pauling-Linus.Pdf

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES L I N U S C A R L P A U L I N G 1901—1994 A Biographical Memoir by J A C K D. D UNITZ Any opinions expressed in this memoir are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Sciences. Biographical Memoir COPYRIGHT 1997 NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS WASHINGTON D.C. LINUS CARL PAULING February 28, 1901–August 19, 1994 BY JACK D. DUNITZ INUS CARL PAULING was born in Portland, Oregon, on LFebruary 28, 1901, and died at his ranch at Big Sur, California, on August 19, 1994. In 1922 he married Ava Helen Miller (died 1981), who bore him four children: Linus Carl, Peter Jeffress, Linda Helen (Kamb), and Edward Crellin. Pauling is widely considered the greatest chemist of this century. Most scientists create a niche for themselves, an area where they feel secure, but Pauling had an enormously wide range of scientific interests: quantum mechanics, crys- tallography, mineralogy, structural chemistry, anesthesia, immunology, medicine, evolution. In all these fields and especially in the border regions between them, he saw where the problems lay, and, backed by his speedy assimilation of the essential facts and by his prodigious memory, he made distinctive and decisive contributions. He is best known, perhaps, for his insights into chemical bonding, for the discovery of the principal elements of protein secondary structure, the alpha-helix and the beta-sheet, and for the first identification of a molecular disease (sickle-cell ane- mia), but there are a multitude of other important contri- This biographical memoir was prepared for publication by both The Royal Society of London and the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. -

ARIE SKLODOWSKA CURIE Opened up the Science of Radioactivity

ARIE SKLODOWSKA CURIE opened up the science of radioactivity. She is best known as the discoverer of the radioactive elements polonium and radium and as the first person to win two Nobel prizes. For scientists and the public, her radium was a key to a basic change in our understanding of matter and energy. Her work not only influenced the development of fundamental science but also ushered in a new era in medical research and treatment. This file contains most of the text of the Web exhibit “Marie Curie and the Science of Radioactivity” at http://www.aip.org/history/curie/contents.htm. You must visit the Web exhibit to explore hyperlinks within the exhibit and to other exhibits. Material in this document is copyright © American Institute of Physics and Naomi Pasachoff and is based on the book Marie Curie and the Science of Radioactivity by Naomi Pasachoff, Oxford University Press, copyright © 1996 by Naomi Pasachoff. Site created 2000, revised May 2005 http://www.aip.org/history/curie/contents.htm Page 1 of 79 Table of Contents Polish Girlhood (1867-1891) 3 Nation and Family 3 The Floating University 6 The Governess 6 The Periodic Table of Elements 10 Dmitri Ivanovich Mendeleev (1834-1907) 10 Elements and Their Properties 10 Classifying the Elements 12 A Student in Paris (1891-1897) 13 Years of Study 13 Love and Marriage 15 Working Wife and Mother 18 Work and Family 20 Pierre Curie (1859-1906) 21 Radioactivity: The Unstable Nucleus and its Uses 23 Uses of Radioactivity 25 Radium and Radioactivity 26 On a New, Strongly Radio-active Substance -

UC Irvine's School of Social Sciences Global Connect @

1 UC Irvine’s School of Social Sciences Global Connect @ UCI Bringing the World to the Classroom hhtp://hypatia.ss.uci.edu/globalconnect The Dalai Lama Workshop The University of California, Irvine’s Global Connect @ UCI undergraduate interns and graduate student participants created the following workshop options to introduce The Dalai Lama to students in grades 8 – 11. It is designed to introduce His Holiness to students who have no previous knowledge concerning the history, leadership, culture and spiritual orientation of The Dalai Lama. Workshop Rationale: 1) “The Story” (A) is a fictional synopsis of the biography of the Dalai Lama’s life. Once the “Story”(Part A) is read in the classroom the name of the Dalai Lama should be introduced by the teacher. 2) In reviewing the story, the Terms (Part B) employed in the fictionalized story should be presented as a means of introducing the students to the realities that help define The Dalai Lama’s history. 3) To promote a more in-depth understanding of the Tibetan experience, proceed to discuss the Discussion Questions (Part C). 4) The Dalai Lama Biographical Profile Worksheet (Part D) To convert the fictional rendition into a fact based profile, students should complete the biographical worksheet in conjunction with 1) reading the included biographical summary of the Dalai Lama or 2) viewing of Compassion in Exile: The Story of the 14th Dalai Lama (a film by Mickey Lemle (1992). 5) Global Recognition: The Nobel Peace Prize (Part E) Assigned readings reprinted in document: The Presentation Speech by the Nobel Committee Chair (1989) Nobel Peace Prize Acceptance Speech by The 14th Dalai Lama (1989) 6) Philosophical & Spiritual Positions of The Dalai Lama (Part F) As a Nobel Laureate and Tibetan –Buddhist leader, The Dalai Lama has addressed people all over the world. -

Upcoming Events Myron Kayton Science Pub #19: 2020 Physics Nobel Stop the Spread: the Challenge of Prize Winner Dr

@harvardsocal @harvardsocal facebook.com/groups/harvardsocal WWW.HARVARDSOCAL.ORG (310) 546-5252 APRIL 2021 Upcoming Events Myron Kayton Science Pub #19: 2020 Physics Nobel Stop the Spread: The Challenge of Prize Winner Dr. Equitable Vaccine Distribution APRIL 2021 - Date and Time TBA Andrea Ghez Virtual Event Join the Harvard Club of Southern Califor- No charge - RSVP required nia for “From the Possibility to the Certain- ty of a Supermassive Black Hole,” a fascinat- ing talk about the Milky Way presented by Film and Discussion: Black Men Photo: New York Times Dr. Andrea Ghez, 2020 Physics Nobel Prize winner and director of the UCLA Galactic in White Coats - A Film by Dale Center Group. This free Zoom event will be held Sunday, April 25 at Okorodudu, MD 3PM. SUN, APR 11 @ 1:00PM Andrea M. Ghez is one of the world’s leading experts in observational Virtual Event astrophysics and heads UCLA’s Galactic Center Group. She has re- No charge, donation appreciated ceived numerous honors and awards, including the 2020 Nobel Prize in Physics with Reinhard Genzel and Roger Penrose. She is the fourth woman to have received the Physics award. Dr. Ghez is committed to HGSE Event: Gutman Library the communication of science to the general public as well as inspiring Book Talk young girls into science. FRI, APR 23 @ 9:00AM Through the capture and analysis of twenty years of high-resolution Virtual Event imaging, the UCLA Galactic Center Group has moved the case for a No charge - RSVP required supermassive black hole at the center of our galaxy from a possibility to a certainty and provided the best evidence to date for the existence of these truly exotic objects. -

The Federal Government: a Nobel Profession

The Federal Government: A Nobel Profession A Report on Pathbreaking Nobel Laureates in Government 1901 - 2002 INTRODUCTION The Nobel Prize is synonymous with greatness. A list of Nobel Prize winners offers a quick register of the world’s best and brightest, whose accomplishments in literature, economics, medicine, science and peace have enriched the lives of millions. Over the past century, 270 Americans have received the Nobel Prize for innovation and ingenuity. Approximately one-fourth of these distinguished individuals are, or were, federal employees. Their Nobel contributions have resulted in the eradication of polio, the mapping of the human genome, the harnessing of atomic energy, the achievement of peace between nations, and advances in medicine that not only prolong our lives, but “This report should serve improve their quality. as an inspiration and a During Public Employees Recognition Week (May 4-10, 2003), in an effort to recognize and honor the reminder to us all of the ideas and accomplishments of federal workers past and present, the Partnership for Public Service offers innovation and nobility of this report highlighting 50 American Nobel laureates the work civil servants do whose award-winning achievements occurred while they served in government or whose public service every day and its far- work had an impact on their career achievements. They were honored for their contributions in the fields reaching impact.” of Physiology or Medicine, Economic Sciences, and Physics and Chemistry. Also included are five Americans whose work merited the Peace Prize. Despite this legacy of accomplishment, too few Americans see the federal government as an incubator for innovation and discovery. -

Linus Pauling and the Belated Nobel Peace Prize,” Science & Diplomacy, Vol

Peter C. Agre, “Fifty Years Ago: Linus Pauling and the Belated Nobel Peace Prize,” Science & Diplomacy, Vol. 2, No. 4 (December 2013*). http://www.sciencediplomacy.org/letter- field/2013/fifty-years-ago-linus-pauling-and-belated-nobel-peace-prize. This copy is for non-commercial use only. More articles, perspectives, editorials, and letters can be found at www.sciencediplomacy.org. Science & Diplomacy is published by the Center for Science Diplomacy of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), the world’s largest general scientific society. *The complete issue will be posted in December 2013. Fifty Years Ago: Linus Pauling and the Belated Nobel Peace Prize Peter C. Agre RADUATE students have approached me on multiple occasions to inquire Gabout pursuing a career in science diplomacy. My first reaction is to fire back, “And so how is it going in the lab?” This often provokes embarrassment and an occasional confession about the frustrations of being a graduate student. On other occasions I think their questions were primed by the idealism of doing something with importance far beyond the laboratory. Is it possible that extracurricular activities efforts outside of the laboratory might have special value? And to what extent is the credibility in the lab essential for extracurricular attention? It seemed likely that the international network of scientists who know other scientists represents unique opportunities to use science to foster friendships worldwide. This has caused me to reflect on the many interesting people I have encountered during my career in science. A few were particularly inspirational, and of these, Linus Pauling, the fascinating and colorful American scientist, stands out for opening doors both worldwide and here in the United States. -

Nobel in Physics 2020

Physics News Black Holes Are in Sight - Nobel in Physics 2020 G.C. Anupama Indian Institute of Astrophysics, II Block Koramangala, Bengaluru 560034 Email: [email protected] G.C. Anupama is a Senior Professor at the Indian Institute of Astrophysics, Bengaluru. Anupama is an observational astronomer with research interests in the area of time domain astronomy. She has been working on studying the temporal evolution of supernova and nova outbursts, and understanding the physical conditions in these systems. Anupama has also been deeply involved in development of astronomical facilities in the country. Abstract The Nobel Prize in Physics 2020 has been awarded to three scientists. One half of the prize was awarded to Roger Penrose and the other half was jointly awarded to Reinhard Genzel and Andrea Ghez. Penrose’s discovery of the singularity theorem showed black hole formation to be a robust prediction of the general theory of relativity, with these objects forming naturally in overdense regions. On the other hand, painstaking, independent studies of the motion of stars over nearly three decades by Genzel and Ghez led to the discovery of a supermassive compact object at the centre of our Galaxy, that can only be a black hole. More recent observations have enabled detection of the relativistic precession of the orbit of the star closest to the Galactic centre, the presence of massive young stars close to the supermassive black hole, and intriguing objects enshrouded in gas and dust in the innermost regions of the nuclear stellar cluster. Introduction objects that, when compressed to a sufficiently small size, The 2020 Nobel Prize in Physics has been awarded for would have a strong gravitational pull leading to an escape "theoretical foundation for black holes and the supermas- velocity exceeding the speed of light. -

The Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prize LEVELED BOOK • W A Reading A–Z Level W Leveled Book Word Count: 1,283 The Connections Nobel Writing Write a historical fiction story from Alfred Nobel’s point of view. Explain Prize why you created the Nobel Prizes and what you hoped they would do for society. Social Studies Write a biography about the life and achievements of a Nobel prizewinner. Include how his or her work continues to make an impact. • • Z Written by Evan Russell T W Visit www.readinga-z.com for thousands of books and materials. www.readinga-z.com Words to Know The Nobel committees injustice controversy nominate Prize diploma physics economics physiology engineer radioactivity foundation scholars Photo Credits: Front cover: © ODD ANDERSEN/AFP/Getty Images; title page: © Fernando Vergara/AP Images; page 3: © Hulton Archive/Getty Images; pages 4, 5 (bottom): © REUTERS; page 5 (top): © Time Life Pictures/Mansell/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images; page 7: © ullstein bild/Getty Images; page 9: © Bettmann/Getty Images; page 10 (top): © AFP/Getty Images; page 10 (bottom): © Alfred Eisenstaedt/Pix Inc./The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images; page 11 (top): © REUTERS/Michael Dalder; page 11 (bottom): © Ulf Andersen/Hulton Archive/Getty Images; page 12 (top): © Michelly Rall/ WireImage/Getty Images; page 12 (bottom): © Nigel Waldron/Getty Images; page 13: © OLIVIER MORIN/AFP/Getty Images; pages 14, 15: © JONATHAN NACKSTRAND/AFP/Getty Images Written by Evan Russell www.readinga-z.com Focus Question The Nobel Prize Level W Leveled Book Correlation © Learning A–Z LEVEL W Written by Evan Russell What is the Nobel Prize, and why Fountas & Pinnell S is it important? All rights reserved. -

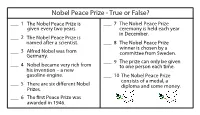

Nobel Peace Prize - True Or False?

Nobel Peace Prize - True or False? ___ 1 T he Nobel Peace Prize is ___ 7 The Nobel Peace Prize given every two years. ceremony is held each year in December. ___ 2 T he Nobel Peace Prize is n amed after a scientist. ___ 8 The Nobel Peace Prize winner is chosen by a ___ 3 A lfred Nobel was from c ommittee from Sweden. G ermany. ___ 9 T he prize can only be given ___ 4 N obel became very rich from t o one person each time. his invention – a new gasoline engine. ___ 10 T he Nobel Peace Prize consists of a medal, a ___ 5 There are six dierent Nobel diploma and some money. Prizes. ___ 6 The rst Peace Prize was awarded in 1946 . Nobel Peace Prize - True or False? ___F 1 T he Nobel Peace Prize is ___T 7 The Nobel Peace Prize given every two years. Every year ceremony is held each year in December. ___T 2 T he Nobel Peace Prize is n amed after a scientist. ___F 8 The Nobel Peace Prize winner is chosen by a Norway ___F 3 A lfred Nobel was from c ommittee from Sweden. G ermany. Sweden ___F 9 T he prize can only be given ___F 4 N obel became very rich from t o one person each time. Two or his invention – a new more gasoline engine. He got rich from ___T 10 T he Nobel Peace Prize dynamite T consists of a medal, a ___ 5 There are six dierent Nobel diploma and some money. -

The Nobel Foundation Annual Review 2019

ANNUAL REVIEW THE NOBEL FOUNDATION • 2019 ANNUAL REVIEW 2019 · THE NOBEL FOUNDATION 1 Cover photo: Previous Nobel Prizes appeared on billboards in Stockholm with the message “Celebrate and understand this year’s Nobel Prizes” during the Nobel Calling Stockholm events in October 2019. On this billboard, right outside Arlanda Airport, the twice Nobel Peace Prize awarded UNHCR is displayed. PHOTO: ALEXANDER MAHMOUD 2 ANNUAL REVIEW 2019 · THE NOBEL FOUNDATION uring the spring of 2020 we Korea, Brazil and Hong Kong. We have are in the midst of a terrible been forced to postpone all of them, crisis. At this writing, it is and instead we are now using our social still impossible to say what media channels to connect with our the consequen c es of the audience around the world. In light Dspreading corona virus might be for our of the current crisis, it is particularly societies and our economies. A pandemic encouraging that we have been able this knows no borders. It strikes us both as year to restart the Nobel Center project. individuals and as a species. The Slussen site in downtown Stockholm The importance of independent is the location chosen for the public research and science is clear. Scientists cultural and science centre we intend were able to quickly map the genetic to build. sequence of the new coronavirus and Lars Heikensten has been Executive have begun working to develop a vaccine. t has truly been a privilege for me to Director of the Nobel Foundation Scientifc analyses and calculations are be able to work with the Nobel Prize since 2011.