Academic Oration 30 November 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Die Woche Spezial

In cooperation with DIE WOCHE SPEZIAL >> Autographs>vs.>#NobelSelfie Special >> Big>Data>–>not>a>big>deal,> Edition just>another>tool >> Why>Don’t>Grasshoppers> Catch>Colds? SCIENCE SUMMIT The>64th>Lindau>Nobel>Laureate>Meeting> devoted>to>Physiology>and>Medicine More than 600 young scientists came to Lindau to meet 37 Nobel laureates CAREER WONGSANIT > Women>to>Women: SUPHAKIT > / > Science>and>Family FOTOLIA INFLAMMATION The>Stress>of>Ageing > FLASHPICS > / > MEETINGS > FOTOLIA LAUREATE > CANCER RESEARCH NOBEL > LINDAU > / > J.>Michael>Bishop>and GÄRTNER > FLEMMING > JUAN > / the>Discovery>of>the>first> > CHRISTIAN FOTOLIA Human>Oncogene EDITORIAL IMPRESSUM Chefredakteur: Prof. Dr. Carsten Könneker (v.i.S.d.P.) Dear readers, Redaktionsleiter: Dr. Daniel Lingenhöhl Redaktion: Antje Findeklee, Jan Dönges, Dr. Jan Osterkamp where>else>can>aspiring>young>scientists> Ständige Mitarbeiter: Lars Fischer Art Director Digital: Marc Grove meet>the>best>researchers>of>the>world> Layout: Oliver Gabriel Schlussredaktion: Christina Meyberg (Ltg.), casually,>and>discuss>their>research,>or>their> Sigrid Spies, Katharina Werle Bildredaktion: Alice Krüßmann (Ltg.), Anke Lingg, Gabriela Rabe work>–>or>pressing>global>problems?>Or> Verlag: Spektrum der Wissenschaft Verlagsgesellschaft mbH, Slevogtstraße 3–5, 69126 Heidelberg, Tel. 06221 9126-600, simply>discuss>soccer?>Probably>the>best> Fax 06221 9126-751; Amtsgericht Mannheim, HRB 338114, UStd-Id-Nr. DE147514638 occasion>is>the>annual>Lindau>Nobel>Laure- Geschäftsleitung: Markus Bossle, Thomas Bleck Marketing und Vertrieb: Annette Baumbusch (Ltg.) Leser- und Bestellservice: Helga Emmerich, Sabine Häusser, ate>Meeting>in>the>lovely>Bavarian>town>of> Ute Park, Tel. 06221 9126-743, E-Mail: [email protected] Lindau>on>Lake>Constance. Die Spektrum der Wissenschaft Verlagsgesellschaft mbH ist Kooperati- onspartner des Nationalen Instituts für Wissenschaftskommunikation Daniel>Lingenhöhl> GmbH (NaWik). -

Helicobacter Pylori…

Helicobacter pylori… Medical Wisdom Challenged by a Cocktail bacteria clinging to the tissues s that nagging, burning of his biopsy specimens. He feeling in your stomach worked diligently with his Icaused by stress, excess associate, the Australian acid, eating spicy food, or physician Barry Marshall, in maybe your insensitive boss? culturing what they saw under the microscope, but to no Back in 1981, Barry Marshall avail. However during the didn’t think so. His discovery Easter weekend of 1982, they regarding the true cause of inadvertently left their duodenal and gastric ulcers cultures incubating for five has changed the way we think days; and to their surprise Jay Hardy, CLS, SM (ASCP) about this disease forever. In they discovered the colonies fact, Marshall believed in his cause so strongly that, to Jay Hardy is the founder and prove his theory, he drank a CEO of Hardy Diagnostics. bacterial cocktail that made He began his career in him violently ill. But he microbiology as a Medical proved his case; to the benefit Technologist in Santa of millions of people who Barbara, California. suffer from ulcers. In 1980, he began manufacturing culture media It was known as far back as for the local hospitals. 1875 by German scientists Today, Hardy Diagnostics is that a spiral-shaped bacterium the third largest media manufacturer in the U.S. inhabited the lining of the human stomach. However, To ensure rapid and reliable because this organism was turn around time, Hardy impossible to culture at the Diagnostics maintains six time, it was quickly forgotten. distribution centers, and produces over 2,700 products used in clinical and Fast forward to 1979. -

ILAE Historical Wall02.Indd 10 6/12/09 12:04:44 PM

2000–2009 2001 2002 2003 2005 2006 2007 2008 Tim Hunt Robert Horvitz Sir Peter Mansfi eld Barry Marshall Craig Mello Oliver Smithies Luc Montagnier 2000 2000 2001 2002 2004 2005 2007 2008 Arvid Carlsson Eric Kandel Sir Paul Nurse John Sulston Richard Axel Robin Warren Mario Capecchi Harald zur Hauser Nobel Prizes 2000000 2001001 2002002 2003003 200404 2006006 2007007 2008008 Paul Greengard Leland Hartwell Sydney Brenner Paul Lauterbur Linda Buck Andrew Fire Sir Martin Evans Françoise Barré-Sinoussi in Medicine and Physiology 2000 1st Congress of the Latin American Region – in Santiago 2005 ILAE archives moved to Zurich to become publicly available 2000 Zonismide licensed for epilepsy in the US and indexed 2001 Epilepsia changes publishers – to Blackwell 2005 26th International Epilepsy Congress – 2001 Epilepsia introduces on–line submission and reviewing in Paris with 5060 delegates 2001 24th International Epilepsy Congress – in Buenos Aires 2005 Bangladesh, China, Costa Rica, Cyprus, Kazakhstan, Nicaragua, Pakistan, 2001 Launch of phase 2 of the Global Campaign Against Epilepsy Singapore and the United Arab Emirates join the ILAE in Geneva 2005 Epilepsy Atlas published under the auspices of the Global 2001 Albania, Armenia, Arzerbaijan, Estonia, Honduras, Jamaica, Campaign Against Epilepsy Kyrgyzstan, Iraq, Lebanon, Malta, Malaysia, Nepal , Paraguay, Philippines, Qatar, Senegal, Syria, South Korea and Zimbabwe 2006 1st regional vice–president is elected – from the Asian and join the ILAE, making a total of 81 chapters Oceanian Region -

Nobel Prize Inspiration Initiative in PARTNERSHIP with Spain 2018

Nobel Prize Inspiration Initiative IN PARTNERSHIP WITH Spain 2018 Dossier Nobel Prize Inspiration Initiative (NPII) es un programa global, diseñado para que los Premios Nobel puedan compartir su experiencia personal y su visión sobre la ciencia, inspirando a estudiantes y jóvenes investigadores CUENTA CON UN IMPORTANTE PANEL DE PREMIOS NOBEL Cada evento tiene una duración de 2 o 3 días ▪ Dr. Peter Agre ▪ Dr. Barry Marshall ▪ Dr. Bruce Beutler ▪ Dr. Craig Mello ▪ Dra. Elizabeth Blackburn ▪ Dr. Paul Nurse ▪ Dr. Michael Brown ▪ Dr. Oliver Smithies ▪ Dr. Martin Chalfie ▪ Dr. Françoise Barré-Sinoussi ▪ Dr. Peter Doherty ▪ Dr. Randy Schekman ▪ Dr. Joseph Goldstein ▪ Dr. Harold Varmus ▪ Dr. Tim Hunt ▪ Dr. Brian Kobilka ▪ Dr. Roger Kornberg LAS ACTIVIDADES SE ORGANIZAN EN TORNO A TOPICS QUE PERMITEN COMPARTIR SU VISIÓN SOBRE EL DESARROLLO DE CARRERAS INVESTIGADORAS Los eventos incluyen la celebración de ponencias, ✓ Advice for Young Scientists ✓ Inspiration and Aspiration mesas redondas, entrevistas, sesiones de preguntas ✓ Career Insights ✓ Life after the Nobel Prize y respuestas, paneles de debate, promoviendo ✓ Characteristics of a Scientist ✓ Mentorship especialmente interacciones informales con los ✓ Clinician Scientists ✓ Surprises and Setbacks científicos más jóvenes. ✓ Collaboration ✓ The Nature of Discovery ✓ Communicating Research ✓ Work-Life Balance Los Premios Nobel se reúnen con jóvenes de ✓ Early Life ✓ Your Views diferentes instituciones, universidades, centros de ✓ Getting Started investigación, etc. 2 Los diferentes formatos de -

Close to the Edge: Co-Authorship Proximity of Nobel Laureates in Physiology Or Medicine, 1991 - 2010, to Cross-Disciplinary Brokers

Close to the edge: Co-authorship proximity of Nobel laureates in Physiology or Medicine, 1991 - 2010, to cross-disciplinary brokers Chris Fields 528 Zinnia Court Sonoma, CA 95476 USA fi[email protected] January 2, 2015 Abstract Between 1991 and 2010, 45 scientists were honored with Nobel prizes in Physiology or Medicine. It is shown that these 45 Nobel laureates are separated, on average, by at most 2.8 co-authorship steps from at least one cross-disciplinary broker, defined as a researcher who has published co-authored papers both in some biomedical discipline and in some non-biomedical discipline. If Nobel laureates in Physiology or Medicine and their immediate collaborators can be regarded as forming the intuitive “center” of the biomedical sciences, then at least for this 20-year sample of Nobel laureates, the center of the biomedical sciences within the co-authorship graph of all of the sciences is closer to the edges of multiple non-biomedical disciplines than typical biomedical researchers are to each other. Keywords: Biomedicine; Co-authorship graphs; Cross-disciplinary brokerage; Graph cen- trality; Preferential attachment Running head: Proximity of Nobel laureates to cross-disciplinary brokers 1 1 Introduction It is intuitively tempting to visualize scientific disciplines as spheres, with highly produc- tive, well-funded intellectual and political leaders such as Nobel laureates occupying their centers and less productive, less well-funded researchers being increasingly peripheral. As preferential attachment mechanisms as well as the economics of employment tend to give the well-known and well-funded more collaborators than the less well-known and less well- funded (e.g. -

Microbiology World Nov – Dec 2013 ISSN 2350 - 8774

Microbiology World Nov – Dec 2013 ISSN 2350 - 8774 www.microbiologyworld.com www.facebook.com/MicrobiologyWorld ~ 1 ~ Microbiology World Nov – Dec 2013 ISSN 2350 - 8774 President Mobeen Syed, M.D. King Endward Medical University Lahore MSc. from ASD, BSc. from Punjab University D-Lab from MIT MA USA Vice-President Sudheer Kumar Aluru, Ph.D Human Genetics, Sri Venkateswara University, India HOD of Biology Department (Narayana Institutions) Managing Director Dr. D K Acharya, Ph.D Asst Prof., Biotech Dept. A. M. Collage of Science, Management and Computer Technology, India Chief Editor Mr. Sagar Aryal Medical Microbiology (M.Sc), Nepal Reviewers Mr. Samir Aga Department of Immunological Diseases Medical Technologist, Iraq Mr. Saumyadip Sarkar, Ph.D ELSEVIER Student Ambassador South Asia, Reed Elsevier (UK) M.Sc., Research Scholar (Human Genetics), India Editors Dr. Sao Bang Hanoi Medical University Dean of Microbiology Department (Provincial Hospital) Microbiology Specialist, Vietnam Mr. Tankeshwar Acharya Lecturer: Patan Academy of Health Sciences (PAHS) Medical Microbiology, Nepal Mr. Avishekh Gautam Lecturer: St. Xavier‘s College Medical Microbiology, Nepal Mr. Manish Thapaliya Lecturer: St. Xavier’s College Food Microbiology, Nepal www.microbiologyworld.com www.facebook.com/MicrobiologyWorld ~ 2 ~ Microbiology World Nov – Dec 2013 ISSN 2350 - 8774 Table of Content Page No. Nobel prize winners in Microbiology, Immunology and Genetics 4-7 Genetic Background of Alzheimer’s Disease 8-10 Interview with Dr. Ayush Kumar 11-13 Microbiology and art: A comfortable combination? 14-17 Research Process 18-21 Non Treponemal Tests 22-25 Cultivation of viruses: Cell culture systems 26-29 Immunoglobulin’s in Periodontitis 30-33 Online Microbiology Course 34-36 www.microbiologyworld.com www.facebook.com/MicrobiologyWorld ~ 3 ~ Microbiology World Nov – Dec 2013 ISSN 2350 - 8774 NOBEL PRIZE WINNERS IN MICROBIOLOGY, IMMUNOLOGY AND GENETICS 2011: Bruce A. -

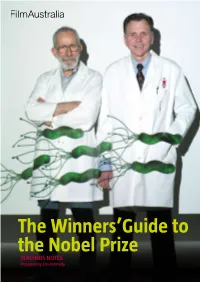

The Winners'guide to the Nobel Prize

The Winners’Guide to the Nobel Prize TEACHERS NOTES Prepared by Cris Kennedy THE WINNERS’ GUIDE TO THE NOBEL PRIZE TEACHERS Notes PAGE 1 Synopsis What does it take to win a Nobel Prize? Guts? Brilliance? Eccentricity? This film travels behind the scenes of the world’s most prestigious prize and into the minds of two of the people who have reached this pinnacle of excellence. In the most isolated capital city in the world, Perth, Western Australia, two scientists are interrupted while enjoying their fish and chips lunch by a phone call from Stockholm, Sweden. They have just been informed that they have been awarded the 2005 Nobel Prize for Medicine and could they make it to the awards ceremony? Australian scientists Barry Marshall and Robin Warren journey to the prize-winners’ podium is more than just a trip to the opposite side of the world to sub-zero temperatures, cultural pomp and extreme Swedish scheduling—it has been a career of trial and error, endless research and Aussie-battler-style stubborn determination. Today, this odd couple of science travel the globe as heroes—ambassadors to the science world—but it was 23 years ago in a modest hospital laboratory in Perth, that Marshall and Warren discovered a bacterium that survived in the human stomach that they called Helicobacter pylori. They believed that this bacterium, not stress, caused gastritis and peptic stomach ulcers, much to the chagrin of the medical world, which at the time scorned them. After years of careful observation, luck and persistence, they finally had the breakthrough they needed, but not before Marshall infected himself, using his own body as a guinea pig to test their theory. -

Probiotics and Helicobacter Pylori

22 Probiotics and Helicobacter pylori Adam S. Kim, MD Helicobacter pylori is one of the most common pathogens in the world. It has infected humans for at least 3000 years, and traces of it have been found in the feces of mum- mified human remains from the South American Andes.1 It was first recognized in the late nineteenth century by Italian pathologists who found spiral bacteria in the stomach of dogs.2 In the early twentieth century, spiral bacteria were found in the stomach of humans.3 These bacteria did not grow in culture, were thought to be an oral contaminant, and were mostly forgotten until the 1980s. Barry Marshall and J. Robin Warren studied these spiral or curved bacteria and later received the 2005 Nobel Prize in Medicine for their early descriptions of H. pylori and its association with human diseases. They first published their discoveries on curved bacilli in the stomach in The Lancet in 1984.4 In this early case series, they reported on 100 consecutive patients undergoing gastroscopy in Perth, Australia. Spiral or curved bacilli were found in 58% of patients and in 87% of patients with an ulcer. They were only able to culture bacilli in 11 subjects, and they described a Gram-negative microaerophilic species related to Campylobacter. They also found that the bacilli was related to the histologic finding of gastritis, and bacilli were found in 30 out of 40 (75%) patients with gastritis, but only 1 out of 29 (3%) patients without gastritis. At the time, colonization with C. pyloridis was not associated with any clinical symptoms, and it was not clear if the bacteria were the cause of peptic ulcer or gastritis. -

List of Nobel Laureates 1

List of Nobel laureates 1 List of Nobel laureates The Nobel Prizes (Swedish: Nobelpriset, Norwegian: Nobelprisen) are awarded annually by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, the Swedish Academy, the Karolinska Institute, and the Norwegian Nobel Committee to individuals and organizations who make outstanding contributions in the fields of chemistry, physics, literature, peace, and physiology or medicine.[1] They were established by the 1895 will of Alfred Nobel, which dictates that the awards should be administered by the Nobel Foundation. Another prize, the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences, was established in 1968 by the Sveriges Riksbank, the central bank of Sweden, for contributors to the field of economics.[2] Each prize is awarded by a separate committee; the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences awards the Prizes in Physics, Chemistry, and Economics, the Karolinska Institute awards the Prize in Physiology or Medicine, and the Norwegian Nobel Committee awards the Prize in Peace.[3] Each recipient receives a medal, a diploma and a monetary award that has varied throughout the years.[2] In 1901, the recipients of the first Nobel Prizes were given 150,782 SEK, which is equal to 7,731,004 SEK in December 2007. In 2008, the winners were awarded a prize amount of 10,000,000 SEK.[4] The awards are presented in Stockholm in an annual ceremony on December 10, the anniversary of Nobel's death.[5] As of 2011, 826 individuals and 20 organizations have been awarded a Nobel Prize, including 69 winners of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences.[6] Four Nobel laureates were not permitted by their governments to accept the Nobel Prize. -

1901-2009 NOBEL PRIZE:1901-2009 O Prêmio Nobel De Medicina Desse Ano Foi Entregue a Elizabeth Blackbur

EDITORIAL PRÊMIO NOBEL: 1901-2009 NOBEL PRIZE:1901-2009 Rosa Lúcia Vieira Maidana, Francisco Veríssimo Veronese, Sandra Pinho Silveiro O prêmio Nobel de Medicina desse ano foi entregue a Elizabeth Blackburn, Jack Szostak e Carol Greider (Figura 1) por terem elucidado a estrutura e o processo de manutenção dos telômeros, como descrevem didaticamente Jardim et al. nesse volume da revista (1). Elizabeth Blackburn (University of California, San Francisco, EUA), Jack Szostak (Harvard Medical School, Boston, EUA) e Carol Greider (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, EUA) descobriram que os telômeros são sequências de DNA situados nas extremidades dos cromossomos e possuem uma estrutura que protege os cromossomos de danos como a erosão. Também de- monstraram que uma enzima específica, a telomerase (descoberta em 1984 por Elizabeth Blackburn e sua então assistente Carol Greider), está envolvida no processo de reparação dos cromossomos após a mitose celular. Como descrevem Calado e Young em revisão publicada em dezembro de 2009 no New England Journal of Medicine (2), os telômeros e a telomerase são protetores contra danos ao genoma que podem surgir de uma replicação assimétrica do DNA. Sem os telômeros, o material genético poderia ser perdido toda vez que ocorre uma divisão celular. As implicações clínicas destes processos são importantes, uma vez que alte- rações nos telômeros estão causalmente relacionadas a patologias em que ocorre mutações genéticas, como a anemia aplásica. Telômeros curtos estão associados a risco aumentado de doença cardiovascular, e mutações no gene da telomerase a condições como fibrose pulmonar e hepática e susceptibilidade a alguns tipos de câncer (ex., coloretal, esôfago, leucemia mielóide). -

Australian Chief Scientist

Presentation to the Environmental Health Conference Chief Scientist of Western Australia Professor Peter Klinken September 1st, 2016 Chief Scientist of Western Australia • Report directly to Premier as Minister for Science • Provide independent advice on: − Science and innovation − Broadening the economy − Promoting science • Work closely with the Office of Science to: − Enhance collaboration − Attract investment − Build leading-edge capacity − Promote science policies − Raise public awareness Department of the Premier and Cabinet Chief Scientist of Western Australia Importance of Science Science affects virtually every part of our lives from: • Communication – computers, mobile phones • Health – medicines, treatments • Travel – Cars, planes, boats • Housing – lights, water, heating • Food and drink – quality, quantity • Etc, etc. Department of the Premier and Cabinet Chief Scientist of Western Australia Science / Industry Continuum Invention Innovation Development Product 1 3 4 6 7 10 |----------------||--------------------||----------------| Fundamental research Applied R&D/ Translational Industrial/ Commercial Universities / Government agencies / SMEs Industry Research organisations Technology Innovation Centres / Start-ups |______________________________________________| CSIRO/ CRC’s |_________________________________________| Industry Growth Centres Department of the Premier and Cabinet Chief Scientist of Western Australia Importance of Science Lord Alec Broers “The technological revolution has been swift and the pace relentless. -

Peptic Ulcer: Rise and Fall

Wellcome Witnesses to Twentieth Century Medicine PEPTIC ULCER: RISE AND FALL The transcript of a Witness Seminar held at the Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine, London, on 12 May 2000 Volume 14 – November 2002 ©The Trustee of the Wellcome Trust, London, 2002 First published by the Wellcome Trust Centre for the History of Medicine at UCL, 2002 The Wellcome Trust Centre for the History of Medicine at UCL is funded by the Wellcome Trust, which is a registered charity, no. 210183. ISBN 978 085484 084 7 All volumes are freely available online at www.history.qmul.ac.uk/research/modbiomed/wellcome_witnesses/ Please cite as : Christie D A, Tansey E M. (eds) (2002) Peptic Ulcer: Rise and Fall. Wellcome Witnesses to Twentieth Century Medicine, vol. 14. London: Wellcome Trust Centre for the History of Medicine at UCL. Key Front cover photographs, L to R from the top: Sir Patrick Forrest Professor Stewart Goodwin Professor Roger Jones Professor Sir Richard Doll (1912–2005) Dr George Misiewicz, Dr Gerard Crean (1927–2005) Professor Michael Hobsley Dr Gerard Crean (1927–2005), Professor Colm Ó’Moráin Back cover photographs, L to R from the top: Dr Joan Faulkner (Lady Doll, 1914–2001) Dr John Wood, Professor Graham Dockray Dr Booth Danesh Professor Kenneth McColl Sir James Black (1924–2009), Dr Gerard Crean (1927–2005) Dr Nelson Coghill (1912–2002), Mr Frank Tovey Professor Roy Pounder (chair), Professor Hugh Baron Dr John Paulley, Sir Richard Doll (1912–2005) CONTENTS Introduction Sir Christopher Booth i Witness Seminars: Meetings and publications;Acknowledgements E M Tansey and D A Christie iii Transcript Edited by D A Christie and E M Tansey 1 Biographical notes 113 Glossary 123 Appendix A Surgical Procedures 127 Appendix B Chemical Structures 128 Index 133 List of plates Figure 1 Age-specific duodenal ulcer perforation rates in England and Wales.