An Experience Much Worse Than Rape: the End of Force-Feeding?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

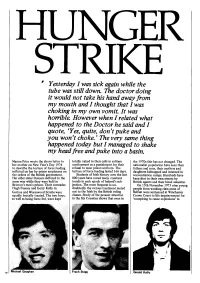

Article on Hungerstrike

" Yesterday I was sick again while the tube was still down. The doctor doing it would not take his hand away [rom my mouth and I thought that I was choking in my own vomit. It was homble. However when I related what happened to the Doctor he said and I quote, 'Yes, quite, don'tpuke and you won't choke. ' The very same thing happened today but I managed to shake my head [ree and puke into a basin. Marian Price wrote the above letter to totaHy naked in their ceHs in solitary the 1970s this has not changed. The her mother on New Year's Day 1974 confinement as a punishment for their nationalist population have seen their to describe the torture of force feeding refusal to wear prison uniform. The fathers and sons, their mothers and inflicted on her by prison employees on torture of force feeding lasted 166 days. daughters kidnapped and interned in the orders of the British government. Students of Irish history over the last concentration camps. Hundreds have Her eIder sister Dolours suffered in the 800 years have noted many constant been shot in their own streets by same way while they were held in trends in each epoch of Ireland's sub• British agents and their hired assassins. Brixton's men's prison. Their comrades jection. The most frequent is un• On 15th November 1973 nine young Hugh Feeney and Gerry KeHy in doubtedly the vicious treatment meted people from working class areas of Gartree and Wormwood Scrubs were out to the Irish by the British ruling Belfast were sentenced at Winchester equally brutally treated. -

The Path to Revolutionary Violence Within the Weather Underground and Provisional IRA

The Path to Revolutionary Violence within the Weather Underground and Provisional IRA Edward Moran HIS 492: Seminar in History December 17, 2019 Moran 1 The 1960’s was a decade defined by a spirit of activism and advocacy for change among oppressed populations worldwide. While the methods for enacting change varied across nations and peoples, early movements such as that for civil rights in America were often committed to peaceful modes of protest and passive resistance. However, the closing years of the decade and the dawn of the 1970’s saw the patterned global spread of increasingly militant tactics used in situations of political and social unrest. The Weather Underground Organization (WUO) in America and the Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA) in Ireland, two such paramilitaries, comprised young activists previously involved in the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and the Northern Irish Civil Rights Association (NICRA) respectively. What caused them to renounce the non-violent methods of the Students for a Democratic Society and the Northern Irish Civil Rights Association for the militant tactics of the Weather Underground and Irish Republican Army, respectively? An analysis of contemporary source materials, along with more recent scholarly works, reveals that violent state reactions to more passive forms of demonstration in the United States and Northern Ireland drove peaceful activists toward militancy. In the case of both the Weather Underground and the Provisional Irish Republican Army in the closing years of the 1960s and early years of the 1970s, the bulk of combatants were young people with previous experience in more peaceful campaigns for civil rights and social justice. -

Memory, Place and Gender: Armagh Stories: Voices from the Gaol Cahal Mclaughlin, Memory Studies Journal, September 2017

Memory, Place and Gender: Armagh Stories: Voices from the Gaol Cahal McLaughlin, Memory Studies Journal, September 2017. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1750698017730872 Abstract The film Armagh Stories: Voices from the Gaol (2015)1 is a documentary film edited from the Prisons Memory Archive2 and offers perspectives from those who passed through Armagh Gaol, which housed mostly female prisoners during the political conflict in and about Northern Ireland, known as the Troubles. Armagh Stories is an attempt to represent the experiences of prison staff, prisoners, tutors, a solicitor, chaplain and doctor in ways that are ethically inclusive and aesthetically relevant. By reflecting on the practice of participatory storytelling and its reception in a society transitioning out of violence, I investigate how memory, place and gender combine to suggest ways of addressing the legacy of a conflicted past in a contested present. Keywords documentary film, female, performing memory, prison, Troubles Introduction The Prisons Memory Archive (PMA) is a collection of 175 filmed interviews recorded inside Armagh Gaol in 2006 and the Maze and Long Kesh Prison in 2007 (Figures 1 and 2). The protocols3 of co-ownership, inclusivity and life storytelling underpinned both the original recordings and subsequent film outputs that include Jolene Mairs Dyer’s (2011)4 Unseen Women and Laura Aguiar’s We Were There (2014).5 Funding was secured from the Community Relations Council’s Media Fund in 2015 to edit a 1-hour documentary on Armagh Goal, and two editors were employed over a 6-month period to work with me acting as director. Among the possible themes that can be excavated from the PMA’s 300 hours of audiovisual material, it was felt that since the representation of women in the Troubles has been particularly downplayed, foregrounding their experiences could help rebalance what is publicly available. -

Written Answers to Questions Official Report (Hansard)

Written Answers to Questions Official Report (Hansard) Friday 22 June 2012 Volume 76, No WA1 This publication contains the written answers to questions tabled by Members. The content of the responses is as received at the time from the relevant Minister or representative of the Assembly Commission and has not been subject to the official reporting process or changed in any way. Contents Written Answers to Questions Office of the First Minister and deputy First Minister ................................................................... WA 1 Department of Agriculture and Rural Development ...................................................................... WA 5 Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure .................................................................................. WA 23 Department of Education ........................................................................................................ WA 27 Department for Employment and Learning ................................................................................ WA 36 Department of Enterprise, Trade and Investment ...................................................................... WA 40 Department of the Environment ............................................................................................... WA 44 Department of Finance and Personnel ................................................................................... WA 115 Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety ......................................................... WA -

Socialist Fight No.10

Socialist Fight Issue No. 10 Autumn 2012 Price: Concessions: 50p, Waged: £2.00 €3 Editorial: “Basic national loyalty and patriotism” and the US proxy war in Syria Ali Zein Al-Abidin Al-barri, summarily murdered with 14 of his men by the FSA for defending Aleppo against pro- imperialist reaction funded by Turkey, Saudi Arabia and Qatar in another US-sponsored counter-revolution in the region Page 10-11: The Counihan-Sanchez family; Page 24: What really is imperialism? Contents a story of Cameron’s Britain. By Farooq Sulehria. Page 2: Editorial: “Basic national loyalty Page 12: FREE The MOVE 9; Ona MOVE for Page 26: Thirty Years in a Turtle-Neck and patriotism” and the US proxy war. our Children! By Cinead D and Patrick Sweater, Review by Laurence Humphries. Page 4: Rank and file conference Conway Murphy. Page 27: Revolutionary communist at Hall 11th August, By Laurence Humphries. Page 13: Letters page, The French Elec- work: a political biography of Bert Ramel- Page 4: London bus drivers Olympics’ bo- tions. son, Review by Laurence Humphries. nus: Well done the drivers! - London GRL, Page 14: Response to Jim Creggan's By Ray Page 29: Queensland: Will the Unions Step On Diversions and ‘Total Victory’ By a Rising. Up? By Aggie McCallum – Australia London bus driver. Page 17: The imperialist degeneration of Page 30: LETTER FROM TPR TO LC AND Page 6: Questions from the IRPSG . sport, By Yuri Iskhandar and Humberto REPLY. Christian Armenteros and Hum- Page 7: REPORT OF THE MEETING AT THE Rodrigues. berto Rodrigues. IRISH EMBASSY 31st JULY 2012 Page 20: A materialist world-view, Face- Page 31: Cosatu – Tied to the Alliance and Page 8: Irish Left ignores plight of Irish book debate. -

Challenging the People, the State and the Patriarchy in 1980S Irish Theatre

Provided by the author(s) and NUI Galway in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite the published version when available. Title Provoking performance: challenging the people, the state and the patriarchy in 1980s Irish Theatre Author(s) O'Beirne, Patricia Publication Date 2018-08-28 Publisher NUI Galway Item record http://hdl.handle.net/10379/14942 Downloaded 2021-09-27T14:54:59Z Some rights reserved. For more information, please see the item record link above. Provoking Performance: Challenging the People, the State and the Patriarchy in 1980s Irish Theatre Candidate: Patricia O’Beirne Supervisor: Dr. Ian Walsh School: School of Humanities Discipline: Drama and Theatre Studies Institution: National University of Ireland, Galway Submission Date: August 2018 Summary of Contents: Provoking Performance: Challenging the People, the State and the Patriarchy in 1980s Irish Theatre This thesis offers new perspectives and knowledge to the discipline of Irish theatre studies and historiography and addresses an overlooked period of Irish theatre. It aims to investigate playwriting and theatre-making in the Republic of Ireland during the 1980s. Theatre’s response to failures of the Irish state, to the civil war in Northern Ireland, and to feminist and working-class concerns are explored in this thesis; it is as much an exploration of the 1980s as it is of plays and playwrights during the decade. As identified by a literature review, scholarly and critical attention during the 1980s was drawn towards Northern Ireland where playwrights were engaging directly with the conflict in Northern Ireland. This means that proportionally the work of many playwrights in the Republic remains unexamined and unpublished. -

THE APPARATUS of IMPUNITY? Human Rights Violations and the Northern Ireland Conflict: a Narrative of Official Limitations on Post-Agreement Investigative Mechanisms

THE APPARATUS OF IMPUNITY? Human rights violations and the Northern Ireland conflict: a narrative of official limitations on post-Agreement investigative mechanisms Committee on the Administration of Justice January 2015 The Apparatus of Impunity? Committee on the Administration of Justice (CAJ) © Committee on the Administration of Justice January 2015 The material may be reproduced, free of charge, in any format or medium without specific permission, provided the reproduction is not for financial or material gain.The material must be reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading context. If the material is to be republished or issued to others, acknowledgement must be given to its source, copyright status, and date of publication. This publication is available on our website. CAJ Committee on the Administration of Justice 2nd Floor, Sturgen Building 9-15 Queen Street Belfast BT1 6EA Tel: 028 9031 6000 Fax: 028 9031 4583 [email protected] www.caj.org.uk ISBN 978 1 873285 94 7 The Apparatus of Impunity? Committee on the Administration of Justice (CAJ) THE APPARATUS OF IMPUNITY? Human rights violations and the Northern Ireland conflict: a narrative of official limitations on post-Agreement investigative mechanisms Committee on the Administration of Justice January 2015 The Apparatus of Impunity? Committee on the Administration of Justice (CAJ) Recent comments from key Council of Europe and UN human rights bodies in relation to existing mechanisms investigating the conflict in Northern Ireland: The absence of any plausible explanation for the failure to collect key evidence at the time when this was possible, and for attempts to even obstruct this process, should be treated with particular vigilance. -

Appendix List of Interviews*

Appendix List of Interviews* Name Date Personal Interview No. 1 29 August 2000 Personal Interview No. 2 12 September 2000 Personal Interview No. 3 18 September 2000 Personal Interview No. 4 6 October 2000 Personal Interview No. 5 16 October 2000 Personal Interview No. 6 17 October 2000 Personal Interview No. 7 18 October 2000 Personal Interview No. 8: Oonagh Marron (A) 17 October 2000 Personal Interview No. 9: Oonagh Marron (B) 23 October 2000 Personal Interview No. 10: Helena Schlindwein 28 October 2000 Personal Interview No. 11 30 October 2000 Personal Interview No. 12 1 November 2000 Personal Interview No. 13 1 November 2000 Personal Interview No. 14: Claire Hackett 7 November 2000 Personal Interview No. 15: Meta Auden 15 November 2000 Personal Interview No. 16 1 June 2000 Personal Interview Maggie Feeley 30 August 2005 Personal Interview No. 18 4 August 2009 Personal Interview No. 19: Marie Mulholland 27 August 2009 Personal Interview No. 20 3 February 2010 Personal Interview No. 21A (joint interview) 23 February 2010 Personal Interview No. 21B (joint interview) 23 February 2010 * Locations are omitted from this list so as to preserve the identity of the respondents. 203 Notes 1 Introduction: Rethinking Women and Nationalism 1 . I will return to this argument in a subsequent section dedicated to women’s victimisation as ‘women as reproducers’ of the nation. See also, Beverly Allen, Rape Warfare: The Hidden Genocide in Bosnia-Herzegovina (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 1996); Alexandra Stiglmayer, (ed.), Mass Rape: The War Against Women in Bosnia- Herzegovina (Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 1994); Carolyn Nordstrom, Fieldwork Under Fire: Contemporary Studies of Violence and Survival (Berkeley: University of California, 1995); Jill Benderly, ‘Rape, feminism, and nationalism in the war in Yugoslav successor states’ in Lois West, ed., Feminist Nationalism (London and New Tork: Routledge, 1997); Cynthia Enloe, ‘When soldiers rape’ in Maneuvers: The International Politics of Militarizing Women’s Lives (Berkeley: University of California, 2000). -

Free Salameh Kaileh and All Socialist and Working Class Militants, No Support to the Syrian Counter-Revolution Led by the Free Syrian Army and Imperialism

Socialist Fight Issue No. 9 Summer 2012 Price: Concessions: 50p, Waged: £2.00, €3.00 Greece: Trotskyist class politics not anti-austerity Popular Frontism Contents Page 2: Editorial: Greece: Trotskyist class politics not anti- austerity Popular Frontism. Page 3: GRL Motion of Support to Construction R+F. Page 4: Diversion: Stuff the £500 Olympics bonus; Where We Stand – Socialist Fight EB. Page 5: Motion to the GRL NC on 12 May on the Labour party and Labour Representation Committee. Page 6: Leitrim woman is honoured by NICRA co-founder as the ‘prisoners’ friend’ IRPSG report. Page 7: Support Republican Prisoners - Join the Protests! Page 8: The framing of Michael McKevitt - Part two By Mi- chael Holden. Page 9: Fascists attack Irish March By Charlie Walsh. Page 10: Today, 14 May, is Thaer Halahleh's 77th day on The Libyan ‘revolution’, “... Lenin warned against pre- hunger strike. maturely confronting respected native institutions, Page 11: May Day Greetings from the LCFI to the Interna- tional Working Class. even when these clearly violated communist princi- Page 12: The Malvinas: the imperialist offensive in the ples and Soviet law. Instead he proposed to use the South Atlantic By the LCFI. Soviet state power to systematically undermine them Page 14: Cultural Imperialism; Ireland, Workers Power and while simultaneously demonstrating the superiority the Sparts By Gerry Downing. of Soviet institutions, a policy which had worked well Page 17: David North’s SEP; a backward, workerist/ against the powerful Russian Orthodox Church.” reductionalist political current By Tony Fox. Dale Ross (D. L. Reissner), ‘Women and Revolution', ‘Early Bolshevik Work Page 19: Tariq Mehanna’s powerful sentencing statement among Women of the Soviet East’ (Issue No. -

Irish Film and Television - 2018

Estudios Irlandeses, Issue 14, March 2019-Feb. 2020, pp. 294-327 __________________________________________________________________________________________ AEDEI IRISH FILM AND TELEVISION - 2018 THE YEAR IN REVIEW Roddy Flynn, Tony Tracy (eds.) Copyright (c) 2019 by the authors. This text may be archived and redistributed both in electronic form and in hard copy, provided that the author and journal are properly cited and no fee is charged for access. Introduction. Fin de Cinema? The Irish Screen Sector in 2018. Roddy Flynn, Tony Tracy……………...………………………………………………..…..295 Documentary as Diversion: A Mother Brings Her Son to be Shot (Sinéad O’Shea, 2017) Eileen Culloty……………….………..……………….………………………………….…305 In the Name of Peace: John Hume in America (Maurice Fitzpatrick, 2018) Seán Crosson………….…………….………………….………………………….………...308 Déjà Vu? The Audiovisual Action Plan (2018) Roddy Flynn…………………….…………..…………………………..…………………...310 The Lonely Battle of Thomas Reid (Fergal Ward, 2018) Roddy Flynn ………………………………………………………………………………...317 Fear, Loathing (and Industrial Relations) in the Irish film Industry Denis Murphy……………………………………..…………………………..…………….321 Searching for Understanding in Alan Gilsenan’s The Meeting Aileen O’Driscoll……………………………………………………………………………324 ISSN 1699-311X 295 Introduction. Fin de Cinema? The Irish Screen Sector in 2018. Tony Tracy, Roddy Flynn In July 2018, the Irish Film Board announced that it was changing its name to Screen Ireland. It was done with relatively little fanfare or media attention and indeed still has to fully work through: as late as January 2019 Irish films were being simultaneously released into cinemas bearing alternately the Irish Film Board or Screen Ireland logos. Was this the year in review’s defining event or simply a timely re-branding? Either way, what might the change tell us? In announcing the change, a PR release explained that the new name reflects the agency’s “redefined, broadened remit, which has been driven both by the changing and diverse nature of the industry and audience content consumption. -

“To the Extent the Law Allows:” Lessons from the Boston College Subpoenas

J Acad Ethics DOI 10.1007/s10805-012-9172-5 Defending Research Confidentiality “To the Extent the Law Allows:” Lessons From the Boston College Subpoenas Ted Palys & John Lowman # Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht 2012 Abstract Although in the US there have been dozens of subpoenas seeking information gathered by academic researchers under a pledge of confidentiality, few cases have garnered as much attention as the two sets of subpoenas issued to Boston College seeking interviews conducted with IRA operatives who participated in The Belfast Project, an oral history of The Troubles in Northern Ireland. For the researchers and participants, confidentiality was understood to be unlimited, while Boston College has asserted that it pledged confidentiality only “to the extent American law allows.” This a priori limitation to confidentiality is invoked by many researchers and universities in the United States, Canada and Great Britain, but there has been little discussion of what the phrase means and what ethical obligations accompany it. An examination of the researchers’ and Boston College’s behav- iour in relation to the subpoenas provides the basis for that discussion. We conclude that Boston College has provided an example that will be cited for years to come of how not to protect research participants to the extent American law allows. Keywords Research confidentiality . Boston College . Belfast Project . Legal cases . Limited confidentiality . Ethics-first Although in the United States there have been dozens of subpoenas seeking information gathered by academic researchers under a pledge of confidentiality (e.g., Cecil and Wetherington 1996; Lowman and Palys 2001), few cases have garnered as much attention as the two sets of subpoenas issued to Boston College in 2011 by the US Attorney General acting on a request from the United Kingdom under the UK-US Mutual Legal Assistance Treaty (MLAT) regarding criminal matters. -

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

Wednesday Volume 528 18 May 2011 No. 160 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Wednesday 18 May 2011 £5·00 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2011 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Parliamentary Click-Use Licence, available online through The National Archives website at www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/information-management/our-services/parliamentary-licence-information.htm Enquiries to The National Archives, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 4DU; e-mail: [email protected] 323 18 MAY 2011 324 I am sure the Secretary of State will join me in House of Commons congratulating the Police Service of Northern Ireland and the Garda on the recent Northern Ireland weapons Wednesday 18 May 2011 finds in East Tyrone and South Armagh. Will he give an assurance that the amnesty previously offered under the decommissioning legislation to those handing in, The House met at half-past Eleven o’clock and in possession of, such weapons will no longer apply, and that anyone caught in possession of weapons will be brought before the courts and any evidence arising PRAYERS from examination of the weapons will be used in prosecutions? [MR SPEAKER in the Chair] Mr Paterson: I am grateful to the right hon. Gentleman for his question, and I entirely endorse his comments on the co-operation between the PSNI and the Garda and Oral Answers to Questions the recent arms finds in Tyrone. The amnesty to which he refers expired in February 2010, and we have no plans to reintroduce it. There is no place for arms in NORTHERN IRELAND today’s Northern Ireland.