The Path to Revolutionary Violence Within the Weather Underground and Provisional IRA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Personal Account of an American Revolutionary and Member Ofthe Weather Underground

The Personal Account of an American Revolutionary and Member ofthe Weather Underground Mattie Greenwood U.S. in the 20th Century World February, 10"'2006 Mr. Brandt OH GRE 2006 1^u St-Andrew's EPISCOPAL SCHOOL American Century Oral History Project Interviewee Release Form I, I-0\ V 3'CoVXJV 'C\V-\f^Vi\ {\ , hereby give and grant to St. Andrew's (inter\'iewee) Episcopal School the absolute and unqualified right to the use ofmy oral histoiy memoir conducted by VA'^^X'^ -Cx^^V^^ Aon 1/1 lOip . I understand that (student interviewer) (date) the purpose ofthis project is to collect audio- and video-taped oral histories of fust-hand memories ofa particular period or event in history as part ofa classroom project (The American Century Projeci), I understand that these interviews (tapes and transcripts) will be deposited in the Saint Andrew's Episcopal School library and archives for the use by future students, educators and researchers. Responsibility for the creation of derivative works will be at the discretion ofthe librarian, archivist and/or project coordinator. 1 also understand that the tapes and transcripts may be used in public presentations including, but not limited to, books, audio or video documentaries, slide-tape presentations, exhibits, articles, public performance, or presentation on the World Wide Web at the project's web site www.americancenturyproject.org or successor technologies. In making this contract I understand that J am sharing with St. Andrew's Episcopal School librai"y and archives all legal title and literar)' property rights which J have or may be deemed to have in my interview as well as my right, title and interest in any copyright related to this oral history interview which may be secured under the laws now or later in force and effect in the United Slates of America. -

Irish History Links

Irish History topics pulled together by Dan Callaghan NC AOH Historian in 2014 Athenry Castle; http://www.irelandseye.com/aarticles/travel/attractions/castles/Galway/athenry.shtm Brehon Laws of Ireland; http://www.libraryireland.com/Brehon-Laws/Contents.php February 1, in ancient Celtic times, it was the beginning of Spring and later became the feast day for St. Bridget; http://www.chalicecentre.net/imbolc.htm May 1, Begins the Celtic celebration of Beltane, May Day; http://wicca.com/celtic/akasha/beltane.htm. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ February 14, 269, St. Valentine, buried in Dublin; http://homepage.eircom.net/~seanjmurphy/irhismys/valentine.htm March 17, 461, St. Patrick dies, many different reports as to the actual date exist; http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/11554a.htm Dec. 7, 521, St. Columcille is born, http://prayerfoundation.org/favoritemonks/favorite_monks_columcille_columba.htm January 23, 540 A.D., St. Ciarán, started Clonmacnoise Monastery; http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/04065a.htm May 16, 578, Feast Day of St. Brendan; http://parish.saintbrendan.org/church/story.php June 9th, 597, St. Columcille, dies at Iona; http://www.irishcultureandcustoms.com/ASaints/Columcille.html Nov. 23, 615, Irish born St. Columbanus dies, www.newadvent.org/cathen/04137a.htm July 8, 689, St. Killian is put to death; http://allsaintsbrookline.org/celtic_saints/killian.html October 13, 1012, Irish Monk and Bishop St. Colman dies; http://www.stcolman.com/ Nov. 14, 1180, first Irish born Bishop of Dublin, St. Laurence O'Toole, dies, www.newadvent.org/cathen/09091b.htm June 7, 1584, Arch Bishop Dermot O'Hurley is hung by the British for being Catholic; http://www.exclassics.com/foxe/dermot.htm 1600 Sept. -

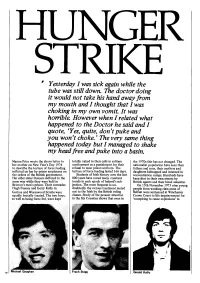

Article on Hungerstrike

" Yesterday I was sick again while the tube was still down. The doctor doing it would not take his hand away [rom my mouth and I thought that I was choking in my own vomit. It was homble. However when I related what happened to the Doctor he said and I quote, 'Yes, quite, don'tpuke and you won't choke. ' The very same thing happened today but I managed to shake my head [ree and puke into a basin. Marian Price wrote the above letter to totaHy naked in their ceHs in solitary the 1970s this has not changed. The her mother on New Year's Day 1974 confinement as a punishment for their nationalist population have seen their to describe the torture of force feeding refusal to wear prison uniform. The fathers and sons, their mothers and inflicted on her by prison employees on torture of force feeding lasted 166 days. daughters kidnapped and interned in the orders of the British government. Students of Irish history over the last concentration camps. Hundreds have Her eIder sister Dolours suffered in the 800 years have noted many constant been shot in their own streets by same way while they were held in trends in each epoch of Ireland's sub• British agents and their hired assassins. Brixton's men's prison. Their comrades jection. The most frequent is un• On 15th November 1973 nine young Hugh Feeney and Gerry KeHy in doubtedly the vicious treatment meted people from working class areas of Gartree and Wormwood Scrubs were out to the Irish by the British ruling Belfast were sentenced at Winchester equally brutally treated. -

A Short History of Irish Memory in the Long Twentieth Century

Thomas Bartlett (ed.), The Cambridge History of Ireland Irish Memory in the Long Twentieth Century (Cambridge, 2018), vol. IV: 1800 to Present would later be developed by his disciple Maurice Halbwachs, who coined the term collective memory ('la memoire collective'). By calling attention to the social frameworks in which memory is framed ('les cadres sociaux de la 23 · memoire'), Halbwachs presented a sound theoretical model for understand ing how individual members of a society collectively remember their past. 3 A Short History of Irish Memory in The impression that modernisation had uprooted people from tradition and the Long Twentieth Century that mass society suffered from atomised impersonality gave birth to a vogue GUY BEINER for commemoration, which was seen as a fundamental act of communal soli darity, in that it projected an illusion of continuity with the past.4 Ireland, outside of Belfast, did not undergo industrialisation on a scale comparable with England, and yet Irish society was not spared the upheaval On the cusp of the twentieth century; Ireland was obsessed with memoriali of modernity. The Great Famine had decimated vernacular Gaelic culture sation. This condition reflected a transnational zeitgeist that was indicative of and resulted in massive emigration. An Irish variant of fin de siecle angst over a crisis of memory throughout Europe. The outcome of rapid modernisa degeneration fed on apprehensions that British rule would ultimately result tion, manifested through changes ushered in by such far-reaching processes in the loss of 'native' identity. The perceived threat to national culture, artic as industrialisation, urbanisation, commercialisation and migration, raised ulated in Douglas Hyde's manifesto on 'The Necessity for De-Anglicising fears that the rituals and customs through which the past had been habitually Ireland' (1892), stimulated a vigorous response in the form of the Irish Revival remembered in the countryside were destined to be swept away. -

Memory, Place and Gender: Armagh Stories: Voices from the Gaol Cahal Mclaughlin, Memory Studies Journal, September 2017

Memory, Place and Gender: Armagh Stories: Voices from the Gaol Cahal McLaughlin, Memory Studies Journal, September 2017. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1750698017730872 Abstract The film Armagh Stories: Voices from the Gaol (2015)1 is a documentary film edited from the Prisons Memory Archive2 and offers perspectives from those who passed through Armagh Gaol, which housed mostly female prisoners during the political conflict in and about Northern Ireland, known as the Troubles. Armagh Stories is an attempt to represent the experiences of prison staff, prisoners, tutors, a solicitor, chaplain and doctor in ways that are ethically inclusive and aesthetically relevant. By reflecting on the practice of participatory storytelling and its reception in a society transitioning out of violence, I investigate how memory, place and gender combine to suggest ways of addressing the legacy of a conflicted past in a contested present. Keywords documentary film, female, performing memory, prison, Troubles Introduction The Prisons Memory Archive (PMA) is a collection of 175 filmed interviews recorded inside Armagh Gaol in 2006 and the Maze and Long Kesh Prison in 2007 (Figures 1 and 2). The protocols3 of co-ownership, inclusivity and life storytelling underpinned both the original recordings and subsequent film outputs that include Jolene Mairs Dyer’s (2011)4 Unseen Women and Laura Aguiar’s We Were There (2014).5 Funding was secured from the Community Relations Council’s Media Fund in 2015 to edit a 1-hour documentary on Armagh Goal, and two editors were employed over a 6-month period to work with me acting as director. Among the possible themes that can be excavated from the PMA’s 300 hours of audiovisual material, it was felt that since the representation of women in the Troubles has been particularly downplayed, foregrounding their experiences could help rebalance what is publicly available. -

Written Answers to Questions Official Report (Hansard)

Written Answers to Questions Official Report (Hansard) Friday 22 June 2012 Volume 76, No WA1 This publication contains the written answers to questions tabled by Members. The content of the responses is as received at the time from the relevant Minister or representative of the Assembly Commission and has not been subject to the official reporting process or changed in any way. Contents Written Answers to Questions Office of the First Minister and deputy First Minister ................................................................... WA 1 Department of Agriculture and Rural Development ...................................................................... WA 5 Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure .................................................................................. WA 23 Department of Education ........................................................................................................ WA 27 Department for Employment and Learning ................................................................................ WA 36 Department of Enterprise, Trade and Investment ...................................................................... WA 40 Department of the Environment ............................................................................................... WA 44 Department of Finance and Personnel ................................................................................... WA 115 Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety ......................................................... WA -

Secret Societies and the Easter Rising

Dominican Scholar Senior Theses Student Scholarship 5-2016 The Power of a Secret: Secret Societies and the Easter Rising Sierra M. Harlan Dominican University of California https://doi.org/10.33015/dominican.edu/2016.HIST.ST.01 Survey: Let us know how this paper benefits you. Recommended Citation Harlan, Sierra M., "The Power of a Secret: Secret Societies and the Easter Rising" (2016). Senior Theses. 49. https://doi.org/10.33015/dominican.edu/2016.HIST.ST.01 This Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Dominican Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Dominican Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE POWER OF A SECRET: SECRET SOCIETIES AND THE EASTER RISING A senior thesis submitted to the History Faculty of Dominican University of California in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Bachelor of Arts in History by Sierra Harlan San Rafael, California May 2016 Harlan ii © 2016 Sierra Harlan All Rights Reserved. Harlan iii Acknowledgments This paper would not have been possible without the amazing support and at times prodding of my family and friends. I specifically would like to thank my father, without him it would not have been possible for me to attend this school or accomplish this paper. He is an amazing man and an entire page could be written about the ways he has helped me, not only this year but my entire life. As a historian I am indebted to a number of librarians and researchers, first and foremost is Michael Pujals, who helped me expedite many problems and was consistently reachable to answer my questions. -

Challenging the People, the State and the Patriarchy in 1980S Irish Theatre

Provided by the author(s) and NUI Galway in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite the published version when available. Title Provoking performance: challenging the people, the state and the patriarchy in 1980s Irish Theatre Author(s) O'Beirne, Patricia Publication Date 2018-08-28 Publisher NUI Galway Item record http://hdl.handle.net/10379/14942 Downloaded 2021-09-27T14:54:59Z Some rights reserved. For more information, please see the item record link above. Provoking Performance: Challenging the People, the State and the Patriarchy in 1980s Irish Theatre Candidate: Patricia O’Beirne Supervisor: Dr. Ian Walsh School: School of Humanities Discipline: Drama and Theatre Studies Institution: National University of Ireland, Galway Submission Date: August 2018 Summary of Contents: Provoking Performance: Challenging the People, the State and the Patriarchy in 1980s Irish Theatre This thesis offers new perspectives and knowledge to the discipline of Irish theatre studies and historiography and addresses an overlooked period of Irish theatre. It aims to investigate playwriting and theatre-making in the Republic of Ireland during the 1980s. Theatre’s response to failures of the Irish state, to the civil war in Northern Ireland, and to feminist and working-class concerns are explored in this thesis; it is as much an exploration of the 1980s as it is of plays and playwrights during the decade. As identified by a literature review, scholarly and critical attention during the 1980s was drawn towards Northern Ireland where playwrights were engaging directly with the conflict in Northern Ireland. This means that proportionally the work of many playwrights in the Republic remains unexamined and unpublished. -

Scholars Week Poster

The Rise and Fall of Students for a Democratic Society Lauren Storch School of Humanities and Global Studies, Ramapo College of New Jersey, Mahwah, NJ, 07430 Introduction The Progressive Labor Party Revolutionary Youth Movement Students for a Democratic Society was created as The Progressive Labor Party joined SDS in In 1969 another radical faction called the an organization whose goals were to activate 1966 as a platform to gain members for their Revolutionary Youth Movement split from SDS after young people into become political vehicles in own organization. The PL faction continued opposing its stance on labor rights. RYM gained order to spread democracy. SDS found its home to grow and dominate SDS. PL activists support by rallying with Hispanic organizations like across college campuses and its numbers soared wanted to emphasize the working class to the Young Lords and Brown Berets, along with the during the early 1960s. SDS became subject to combat issues surrounding workers rights Black Panther Party. RYM eventually split into institutional collapse during the later half of the and Capitalism, while SDS was more another faction within itself called RYM II that decade as internal and external forces conflicted focused on ending the war in Vietnam and positioned itself against the Weathermen. RYM and with the movements overarching ideology. The combating racism. In 1969 SDS removed the RYM II were unstable groups with little to no radical factions that distanced themselves from PL Party from its organization due to a lack institutional structure or strategy, making their efforts SDS contributed to the collapse of the organization of joint fundamental beliefs. -

Four Turning Points in Columbia's History

COLUMBIA columbia university DIGITAL KNOWLEDGE VENTURES OUR PAST ENGAGED: FOUR TURNING POINTS IN COLUMBIA’S HISTORY April 27, 2004 ROBERT McCAUGHEY COLUMBIA '68: A CHAPTER IN THE HISTORY OF STUDENT POWER Welcome and Introduction Eric Foner: Hello everybody. And welcome to the fourth of the four panels' lectures, "Our Past Engaged: Four Turning Points in Columbia's Recent History." I notice that we have a group of guests here. I'm not sure what they are planning or hoping to do, but as long as they are peaceful and quiet and do not disrupt the proceedings, if they want to sit there it's fine with me. On the other hand, I hope and expect that the discussion will go on in the way that we expect here at the University, in a reasoned and academic manner. I was also asked to announce that the previous lectures in this series, as well as much supporting material about the 250th anniversary of Columbia University, is available on the Columbia 250 Web site, which can be accessed through the Columbia Web site—the home page—which you all probably know about. So I'm Eric Foner from the history department, and I've been asked to be the moderator. I'm very happy to be here tonight. And the first thing that I want to do is to identify Professor Robert McCaughey, who is the speaker tonight, but also to indicate that he has really been the one who has organized these sessions. He's written a most remarkable, wonderful book on the history of Columbia, Stand Columbia, and he has been the person who introduced the previous three speakers. -

From Gunmen to Statesmen: the Irish Republican Army and Sinn Fein

From Gunmen to Politicians: The Impact of Terrorism and Political Violence on Twentieth-Century Ireland by Robert W. White Abstract Many terrorist groups, it would seem, cause great turmoil but no lasting impact. This might include radical student groups of the 1960s and terrorist organizations of the 1970s. Yet, we know that in some instances political violence, or revolution, does lead to great social change. Consider Cuba as an example. This might suggest that terrorists and revolutionaries face a zero-sum game: total failure or total victory. There is a middle ground, however. The PLO, as an example, has not achieved an independent Palestine, but who in the 1970s would have imagined a Palestinian Authority led by Yasir Arafat. This case study of the Irish Republican Army and its political wing, Sinn Fein, examines this middle ground in Ireland in the 1916-1948 time period. INTRODUCTION On the surface, it would appear that most terrorist groups flash violently onto the scene and then fade away, without a lasting impact. Whither the Symbionese Liberation Army, the Red Army Faction, and so forth? Yet, a very small number of such organizations, including the African National Congress, seemingly won their war and have brought about massive social change in their respective countries. There is also a middle ground. Some groups, the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), for example, exist for decades and bring about significant change, but (as of yet) have not won their war. It is this middle ground that is examined here, in a case study of the effects of the paramilitary and political campaigns of the Irish Republican Army (IRA) and its political arm, Sinn Fein, in Ireland between 1916 and 1948. -

War of Independence Online Resources

Topic Researchers Online resource General War of Independence https://erinascendantwordpress.wordpress.com/category/irish-war-of-independence/ https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/heritage/century/the-revolution-files https://www.scoilnet.ie/go-to-post-primary/collections/senior-cycle/decade-of-centenaries/the-war-of- independence/ https://www.rte.ie/centuryireland/index.php/articles/irelands-unhappy-new-year-1920-begins-in-violence- and-disorder Decade of Centenaries | Ulster 1885 - 1925 | Timeline https://www.duchas.ie/en/cbes Catalogue - National Library of Ireland 1. Frongoch Prison https://www.rte.ie/centuryireland/index.php/articles/ frongoch-a-day-in-the-life https://www.museum.ie/The-Collections/Frongoch- and-1916 2. The first Dáil Eireann https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/heritage/century/ a-date-with-destiny-the-centenary-of-the-first- d%C3%A1il-1.3762550 https://www.dail100.ie/en http://www.generalmichaelcollins.com/life-times/ rebellion/the-first-dail-1919/ 3. Lincoln Prison https://www.irishcentral.com/roots/eamon-de- valera-prison-escape 4. Soloheadbeg Ambush https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/heritage/century/ soloheadbeg-the-fatal-shots-that-ignited-the-war-of- independence-1.3761334 https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/heritage/century/ the-revolution-files/tipperary-1919-the-woman-who- hid-dan-breen-after-soloheadbeg- ambush-1.4036615 5. Informants and Spies http://www.generalmichaelcollins.com/life-times/ rebellion/intelligence-war/ https://www.historyireland.com/volume-25/issue-3- mayjune-2017/spies-informers-beware/ https://stairnaheireann.net/2018/03/12/an- intelligence-card-from-the-irish-war-of- independence/ 6. Knocklong Ambush Knocklong ambush, on May 13th, 1919 involved a 14-minute gun battle Two RIC men killed in ambush in Knocklong | Century Ireland https://stairnaheireann.net/2017/05/13/otd-in-1919- dan-breen-and-sean-treacy-rescue-their-comrade- sean-hogan-from-a-dublin-cork-train-at-knocklong- co-limerick/ 7.