Appendix List of Interviews*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix 1: Sample Newspapers and Media Coverage

Appendix 1: Sample Newspapers and Media Coverage Sample Newspapers The following newspapers are referred to throughout the monograph as the ‘sample newspapers’ that were collected over the six months data collection period (1 March 2010 to 31 August 2010). Andersonstown News Belfast Telegraph Irish News News Letter North Belfast News South Belfast News Sunday Life Sunday World, Northern Edition In selecting the newspapers, the ideological differences existing within Northern Ireland’s media have been considered and the selection is represen- tative (i.e. The Irish News aligns with the Nationalist viewpoint, whereas the Newsletter aligns with the Unionist viewpoint and the Belfast Telegraph appears not to favour or align with one specific cultural tradition or particular political ethos). © The Author(s) 2018 239 F. Gordon, Children, Young People and the Press in a Transitioning Society, Palgrave Socio-Legal Studies, https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-60682-2 Table A1.1 Sample newspapers circulation figures, December 2010 Circulation Newspaper Type figure Ownership Belfast Telegraph Daily 58,491 Belfast Telegraph Newspapers Irish News Daily 44,222 Irish News Ltd News Letter Daily 23,669 Johnston Publishing (NI) Andersonstown News Twice-weekly 12,090 Belfast Media Group 6,761 (Monday) North Belfast News Weekly 4,438 Belfast Media Group South Belfast News Weekly Not available Belfast Media Group Sunday Life Weekly 54,435 Belfast Telegraph Newspapers Sunday World, Northern Weekly Not available Not available Edition Table A1.2 Other local newspapers cited The following newspapers were collected during July and August 2010 and further news items were accessed from the online archives. -

John F. Morrison Phd Thesis

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by St Andrews Research Repository 'THE AFFIRMATION OF BEHAN?' AN UNDERSTANDING OF THE POLITICISATION PROCESS OF THE PROVISIONAL IRISH REPUBLICAN MOVEMENT THROUGH AN ORGANISATIONAL ANALYSIS OF SPLITS FROM 1969 TO 1997 John F. Morrison A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2010 Full metadata for this item is available in Research@StAndrews:FullText at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/3158 This item is protected by original copyright ‘The Affirmation of Behan?’ An Understanding of the Politicisation Process of the Provisional Irish Republican Movement Through an Organisational Analysis of Splits from 1969 to 1997. John F. Morrison School of International Relations Ph.D. 2010 SUBMISSION OF PHD AND MPHIL THESES REQUIRED DECLARATIONS 1. Candidate’s declarations: I, John F. Morrison, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 82,000 words in length, has been written by me, that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a research student in September 2005 and as a candidate for the degree of Ph.D. in May, 2007; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 2005 and 2010. Date 25-Aug-10 Signature of candidate 2. Supervisor’s declaration: I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of Ph.D. -

The Counter-Aesthetics of Republican Prison Writing

Notes Chapter One Introduction: Taoibh Amuigh agus Faoi Ghlas: The Counter-aesthetics of Republican Prison Writing 1. Gerry Adams, “The Fire,” Cage Eleven (Dingle: Brandon, 1990) 37. 2. Ibid., 46. 3. Pat Magee, Gangsters or Guerillas? (Belfast: Beyond the Pale, 2001) v. 4. David Pierce, ed., Introduction, Irish Writing in the Twentieth Century: A Reader (Cork: Cork University Press, 2000) xl. 5. Ibid. 6. Shiela Roberts, “South African Prison Literature,” Ariel 16.2 (Apr. 1985): 61. 7. Michel Foucault, “Power and Strategies,” Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972–1977, ed. Colin Gordon (New York: Pantheon, 1980) 141–2. 8. In “The Eye of Power,” for instance, Foucault argues, “The tendency of Bentham’s thought [in designing prisons such as the famed Panopticon] is archaic in the importance it gives to the gaze.” In Power/ Knowledge 160. 9. Breyten Breytenbach, The True Confessions of an Albino Terrorist (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1983) 147. 10. Ioan Davies, Writers in Prison (Cambridge, MA: Blackwell, 1990) 4. 11. Ibid. 12. William Wordsworth, “Preface to Lyrical Ballads,” The Norton Anthology of English Literature vol. 2A, 7th edition, ed. M. H. Abrams et al. (New York: W. W. Norton, 2000) 250. 13. Gerry Adams, “Inside Story,” Republican News 16 Aug. 1975: 6. 14. Gerry Adams, “Cage Eleven,” Cage Eleven (Dingle: Brandon, 1990) 20. 15. Wordsworth, “Preface” 249. 16. Ibid., 250. 17. Ibid. 18. Terry Eagleton, The Ideology of the Aesthetic (Cambridge, MA: Blackwell, 1990) 27. 19. W. B. Yeats, Essays and Introductions (New York: Macmillan, 1961) 521–2. 20. Bobby Sands, One Day in My Life (Dublin and Cork: Mercier, 1983) 98. -

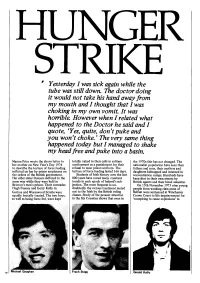

Article on Hungerstrike

" Yesterday I was sick again while the tube was still down. The doctor doing it would not take his hand away [rom my mouth and I thought that I was choking in my own vomit. It was homble. However when I related what happened to the Doctor he said and I quote, 'Yes, quite, don'tpuke and you won't choke. ' The very same thing happened today but I managed to shake my head [ree and puke into a basin. Marian Price wrote the above letter to totaHy naked in their ceHs in solitary the 1970s this has not changed. The her mother on New Year's Day 1974 confinement as a punishment for their nationalist population have seen their to describe the torture of force feeding refusal to wear prison uniform. The fathers and sons, their mothers and inflicted on her by prison employees on torture of force feeding lasted 166 days. daughters kidnapped and interned in the orders of the British government. Students of Irish history over the last concentration camps. Hundreds have Her eIder sister Dolours suffered in the 800 years have noted many constant been shot in their own streets by same way while they were held in trends in each epoch of Ireland's sub• British agents and their hired assassins. Brixton's men's prison. Their comrades jection. The most frequent is un• On 15th November 1973 nine young Hugh Feeney and Gerry KeHy in doubtedly the vicious treatment meted people from working class areas of Gartree and Wormwood Scrubs were out to the Irish by the British ruling Belfast were sentenced at Winchester equally brutally treated. -

Gerry Adams Comments on the Attack in Antrim : Sinn Féin

Gerry Adams comments on the attack in Antrim : Sinn Féin Friday, March 13, 2009 News Feed Comments ● Home ● About ❍ Note about this website ❍ Contact Us ❍ Representatives ❍ Leadership ❍ History ❍ Links ● Ard Fheis 2009 ❍ Clár and Motions ❍ Gerry Adams’ Presidential Address ❍ Martin McGuinness Keynote Speech on Irish Unity ❍ Keynote Economic Address - Mary Lou McDonald MEP ❍ Pat Doherty MP - Opening Address ❍ Gerry Kelly on Justice ❍ Pádraig Mac Lochlainn North West EU Candidate Lisbon Speech ❍ Minister for Agriculture & Rural Development Michelle Gildernew MP ❍ Bairbre de Brún MEP –EU Affairs ● Issues ❍ Irish Unity ❍ Economy ❍ Education ❍ Environment ❍ EU Affairs ❍ Health ❍ Housing ❍ International Affairs http://www.ardfheis.com/?p=628 (1 of 11)13/03/2009 10:19:18 Gerry Adams comments on the attack in Antrim : Sinn Féin ❍ Irish Language & Culture ❍ Justice & the Community ❍ Rural Regeneration ❍ Social Inclusion ❍ Women’s Rights ● Help/Join ❍ Help Sinn Féin ❍ Join Sinn Féin ❍ Friends of Sinn Féin ❍ Cairde Sinn Féin ● Donate ● Social Networks ● Campaign Literature ● Featured Stories ● Gerry Adams Blog ● Latest News ● Photo Gallery ● Speeches Ard Fheis '09 ● Videos ❍ Ard Fheis Videos Browse > Home / Featured Stories / Gerry Adams comments on the attack in Antrim Gerry Adams comments on the attack in Antrim March 10, 2009 by admin Filed under Featured Stories Leave a comment Gerry Adams statement in the Assembly Monday March 9, 2009 http://www.ardfheis.com/?p=628 (2 of 11)13/03/2009 10:19:18 Gerry Adams comments on the attack in Antrim : Sinn Féin —————————————————————————— http://www.ardfheis.com/?p=628 (3 of 11)13/03/2009 10:19:18 Gerry Adams comments on the attack in Antrim : Sinn Féin Gerry Adams Blog Monday March 9th, 2009 The only way to go is forward On Saturday night I was in County Clare. -

Thatcher, Northern Ireland and Anglo-Irish Relations, 1979-1990

From ‘as British as Finchley’ to ‘no selfish strategic interest’: Thatcher, Northern Ireland and Anglo-Irish Relations, 1979-1990 Fiona Diane McKelvey, BA (Hons), MRes Faculty of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences of Ulster University A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Ulster University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2018 I confirm that the word count of this thesis is less than 100,000 words excluding the title page, contents, acknowledgements, summary or abstract, abbreviations, footnotes, diagrams, maps, illustrations, tables, appendices, and references or bibliography Contents Acknowledgements i Abstract ii Abbreviations iii List of Tables v Introduction An Unrequited Love Affair? Unionism and Conservatism, 1885-1979 1 Research Questions, Contribution to Knowledge, Research Methods, Methodology and Structure of Thesis 1 Playing the Orange Card: Westminster and the Home Rule Crises, 1885-1921 10 The Realm of ‘old unhappy far-off things and battles long ago’: Ulster Unionists at Westminster after 1921 18 ‘For God's sake bring me a large Scotch. What a bloody awful country’: 1950-1974 22 Thatcher on the Road to Number Ten, 1975-1979 26 Conclusion 28 Chapter 1 Jack Lynch, Charles J. Haughey and Margaret Thatcher, 1979-1981 31 'Rise and Follow Charlie': Haughey's Journey from the Backbenches to the Taoiseach's Office 34 The Atkins Talks 40 Haughey’s Search for the ‘glittering prize’ 45 The Haughey-Thatcher Meetings 49 Conclusion 65 Chapter 2 Crisis in Ireland: The Hunger Strikes, 1980-1981 -

New Media, Free Expression, and the Offences Against the State Acts

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2020 New Media, Free Expression, and the Offences Against the State Acts Laura K. Donohue Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/2248 https://ssrn.com/abstract=3825722 Laura K. Donohue, New Media, Free Expression, and the Offences Against the State Acts, in The Offences Against the State Act 1939 at 80: A Model Counter-Terrorism Act? 163 (Mark Coen ed., Oxford: Hart Publishing 2021). This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, European Law Commons, Human Rights Law Commons, International Law Commons, Internet Law Commons, Legislation Commons, and the National Security Law Commons New Media, Free Expression, and the Offences Against the State Acts Laura K. Donohue1 Introduction Social media has become an integral part of modern human interaction: as of October 2019, Facebook reported 2.414 billion active users worldwide.2 YouTube, WhatsApp, and Instagram were not far behind, with 2 billion, 1.6 billion, and 1 billion users respectively.3 In Ireland, 3.2 million people (66% of the population) use social media for an average of nearly two hours per day.4 By 2022, the number of domestic Facebook users is expected to reach 2.92 million.5 Forty-one percent of the population uses Instagram (65% daily); 30% uses Twitter (40% daily), and another 30% uses LinkedIn.6 With social media most prevalent amongst the younger generations, these numbers will only rise. -

The Path to Revolutionary Violence Within the Weather Underground and Provisional IRA

The Path to Revolutionary Violence within the Weather Underground and Provisional IRA Edward Moran HIS 492: Seminar in History December 17, 2019 Moran 1 The 1960’s was a decade defined by a spirit of activism and advocacy for change among oppressed populations worldwide. While the methods for enacting change varied across nations and peoples, early movements such as that for civil rights in America were often committed to peaceful modes of protest and passive resistance. However, the closing years of the decade and the dawn of the 1970’s saw the patterned global spread of increasingly militant tactics used in situations of political and social unrest. The Weather Underground Organization (WUO) in America and the Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA) in Ireland, two such paramilitaries, comprised young activists previously involved in the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and the Northern Irish Civil Rights Association (NICRA) respectively. What caused them to renounce the non-violent methods of the Students for a Democratic Society and the Northern Irish Civil Rights Association for the militant tactics of the Weather Underground and Irish Republican Army, respectively? An analysis of contemporary source materials, along with more recent scholarly works, reveals that violent state reactions to more passive forms of demonstration in the United States and Northern Ireland drove peaceful activists toward militancy. In the case of both the Weather Underground and the Provisional Irish Republican Army in the closing years of the 1960s and early years of the 1970s, the bulk of combatants were young people with previous experience in more peaceful campaigns for civil rights and social justice. -

Memory, Place and Gender: Armagh Stories: Voices from the Gaol Cahal Mclaughlin, Memory Studies Journal, September 2017

Memory, Place and Gender: Armagh Stories: Voices from the Gaol Cahal McLaughlin, Memory Studies Journal, September 2017. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1750698017730872 Abstract The film Armagh Stories: Voices from the Gaol (2015)1 is a documentary film edited from the Prisons Memory Archive2 and offers perspectives from those who passed through Armagh Gaol, which housed mostly female prisoners during the political conflict in and about Northern Ireland, known as the Troubles. Armagh Stories is an attempt to represent the experiences of prison staff, prisoners, tutors, a solicitor, chaplain and doctor in ways that are ethically inclusive and aesthetically relevant. By reflecting on the practice of participatory storytelling and its reception in a society transitioning out of violence, I investigate how memory, place and gender combine to suggest ways of addressing the legacy of a conflicted past in a contested present. Keywords documentary film, female, performing memory, prison, Troubles Introduction The Prisons Memory Archive (PMA) is a collection of 175 filmed interviews recorded inside Armagh Gaol in 2006 and the Maze and Long Kesh Prison in 2007 (Figures 1 and 2). The protocols3 of co-ownership, inclusivity and life storytelling underpinned both the original recordings and subsequent film outputs that include Jolene Mairs Dyer’s (2011)4 Unseen Women and Laura Aguiar’s We Were There (2014).5 Funding was secured from the Community Relations Council’s Media Fund in 2015 to edit a 1-hour documentary on Armagh Goal, and two editors were employed over a 6-month period to work with me acting as director. Among the possible themes that can be excavated from the PMA’s 300 hours of audiovisual material, it was felt that since the representation of women in the Troubles has been particularly downplayed, foregrounding their experiences could help rebalance what is publicly available. -

Written Answers to Questions Official Report (Hansard)

Written Answers to Questions Official Report (Hansard) Friday 22 June 2012 Volume 76, No WA1 This publication contains the written answers to questions tabled by Members. The content of the responses is as received at the time from the relevant Minister or representative of the Assembly Commission and has not been subject to the official reporting process or changed in any way. Contents Written Answers to Questions Office of the First Minister and deputy First Minister ................................................................... WA 1 Department of Agriculture and Rural Development ...................................................................... WA 5 Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure .................................................................................. WA 23 Department of Education ........................................................................................................ WA 27 Department for Employment and Learning ................................................................................ WA 36 Department of Enterprise, Trade and Investment ...................................................................... WA 40 Department of the Environment ............................................................................................... WA 44 Department of Finance and Personnel ................................................................................... WA 115 Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety ......................................................... WA -

Handbook of Second Level Educational Research: Breaking the S.E.A.L

Provided by the author(s) and NUI Galway in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite the published version when available. Title Handbook of second level educational research: Breaking the S.E.A.L. Student engagement with archives for learning Author(s) Flynn, Paul; Houlihan, Barry Publication Date 2017-07 Publication Flynn, Paul, & Houlihan, Barry. (2017). Handbook of second Information level educational research: Breaking the S.E.A.L. Student engagement with archives for learning. Galway: NUI Galway. Publisher NUI Galway Item record http://hdl.handle.net/10379/6687 Downloaded 2021-09-24T14:02:50Z Some rights reserved. For more information, please see the item record link above. Handbook of Second Level Educational Research Breaking the S.E.A.L. Student Engagement with Archives for Learning, NUI Galway, 2017 Editors: Paul Flynn and Barry Houlihan ISBN: 978-1-908358-56-1 Table of Contents Foreword 7 Introduction 9 Moneenageisha Community College 10 Alanna O’Reilly Deborah Sampson Gannett and Her Role in the Continental Army During the American Revolutionary War. 11 Mitchelle Dupe The Death of Emmett Till and its Effect on American Civil Rights Movement. 11 Andreea Duma Joan Parlea: His Role in the Germany Army Between 1941-1943. 11 Paddy Hogan An Irishmans' Role in The Suez Crisis. 11 Presentation College Headford 12 Michael McLoughlin Trench Warfare in World War 1 13 Ezra Heraty The Gallant Heroics of Pigeons during the Great War 14 Sophie Smith The White Rose Movement 15 Maggie Larson The Hollywood Blacklist: Influences on Film Content 1933-50 16 Diarmaid Conway Michael Cusack – Gaelic Games Pioneer 18 Ciara Varley Emily Hobhouse in the Anglo-Boer War 19 Andrew Egan !3 The Hunger Striking in Irish Republicanism 21 Joey Maguire Michael Cusack 23 Coláiste Mhuire, Ballygar 24 Mártin Quinn The Iranian Hostage Crisis: How the Canadian Embassy Workers Helped to Rescue the Six Escaped Hostages. -

S.Macw / CV / NCAD

Susan MacWilliam Curriculum Vitae 1 / 8 http://www.susanmacwilliam.com/ Solo Exhibitions 2012 Out of this Worlds, Noxious Sector Projects, Seattle F-L-A-M-M-A-R-I-O-N, Open Space, Victoria, BC 2010 F-L-A-M-M-A-R-I-O-N, aceart inc, Winnipeg Supersense, Higher Bridges Gallery, Enniskillen Susan MacWilliam, Conner Contemporary, Washington DC F-L-A-M-M-A-R-I-O-N, Golden Thread Gallery, Belfast F-L-A-M-M-A-R-I-O-N, NCAD Gallery, Dublin 2009 Remote Viewing, 53rd Venice Biennale 2009, Solo exhibition representing Northern Ireland 13 Roland Gardens, Golden Thread Gallery Project Space, Belfast 2008 Eileen, Gimpel Fils, London Double Vision, Jack the Pelican Presents, New York 13 Roland Gardens, Video Screening, The Parapsychology Foundation Perspectives Lecture Series, Baruch College, City University, New York 2006 Dermo Optics, Likovni Salon, Celje, Slovenia 2006 Susan MacWilliam, Ard Bia Café, Galway 2004 Headbox, Temple Bar Gallery, Dublin 2003 On The Eye, Golden Thread Gallery, Belfast 2002 On The Eye, Butler Gallery, Kilkenny 2001 Susan MacWilliam, Gallery 1, Cornerhouse, Manchester 2000 The Persistence of Vision, Limerick City Gallery of Art, Limerick 1999 Experiment M, Context Gallery, Derry Faint, Old Museum Arts Centre, Belfast 1997 Curtains, Project Arts Centre, Dublin 1995 Liptych II, Crescent Arts Centre, Belfast 1994 Liptych, Harmony Hill Arts Centre, Lisburn List, Street Level Gallery, Irish News Building, Belfast Solo Screenings 2012 Some Ghosts, Dr William G Roll (1926-2012) Memorial, Rhine Research Center, Durham, NC. 2010 F-L-A-M-M-A-R-I-O-N, Sarah Meltzer Gallery, New York.