THE APPARATUS of IMPUNITY? Human Rights Violations and the Northern Ireland Conflict: a Narrative of Official Limitations on Post-Agreement Investigative Mechanisms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Identity, Authority and Myth-Making: Politically-Motivated Prisoners and the Use of Music During the Northern Irish Conflict, 1962 - 2000

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Queen Mary Research Online Identity, authority and myth-making: Politically-motivated prisoners and the use of music during the Northern Irish conflict, 1962 - 2000 Claire Alexandra Green Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 1 I, Claire Alexandra Green, confirm that the research included within this thesis is my own work or that where it has been carried out in collaboration with, or supported by others, that this is duly acknowledged below and my contribution indicated. Previously published material is also acknowledged below. I attest that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge break any UK law, infringe any third party’s copyright or other Intellectual Property Right, or contain any confidential material. I accept that the College has the right to use plagiarism detection software to check the electronic version of the thesis. I confirm that this thesis has not been previously submitted for the award of a degree by this or any other university. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. Signature: Date: 29/04/19 Details of collaboration and publications: ‘It’s All Over: Romantic Relationships, Endurance and Loyalty in the Songs of Northern Irish Politically-Motivated Prisoners’, Estudios Irlandeses, 14, 70-82. 2 Abstract. In this study I examine the use of music by and in relation to politically-motivated prisoners in Northern Ireland, from the mid-1960s until 2000. -

Newshound: Daily Northern Ireland News Catalog - Irish News Article

Newshound: Daily Northern Ireland news catalog - Irish News article Bereaved urge Adams — reveal truth on HOME agents This article appears thanks to the Irish News. History (Allison Morris, Irish News) Subscribe to the Irish News NewsoftheIrish The children of a Co Tyrone couple murdered by loyalists have challenged Sinn Féin president Gerry Adams to call on the IRA to reveal publicly what it knows about British agents Book Reviews working in its ranks. & Book Forum Charlie Fox (63) and his wife Tess (53) were shot at their Search / Archive home in Moy, Co Tyrone, in September 1992 by the UVF. Back to 10/96 Mrs Fox was hit in the back. Her husband was shot in the Papers head. Reference Their children spoke out yesterday (Tuesday) after a Sinn Féin 'march for truth' on Sunday which called for collusion between the British state and loyalists to be exposed and at About which Mr Adams said: "Yes, the British recruited, blackmailed, tricked, intimidated and bribed individual republicans into working for them and I think it would be Contact only right to have this dimension of British strategy investigated also." Leading loyalist Laurence George Maguire was convicted in 1994 of directing the UVF gang responsible for murdering Mr and Mrs Fox. A week before the couple's deaths their son Patrick Fox was jailed for 12 years for possession of explosives. He said yesterday that while he welcomed Mr Adams's call for disclosure on British collusion with loyalists, the truth about republican agents must be revealed. "We know now that there were moves towards a ceasefire being made as far back as 1986," he said. -

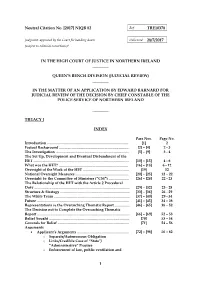

Barnard's (Edward) Application for Judicial Review of The

Neutral Citation No. [2017] NIQB 82 Ref: TRE10378 Judgment: approved by the Court for handing down Delivered: 28/7/2017 (subject to editorial corrections)* IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE IN NORTHERN IRELAND ________ QUEEN’S BENCH DIVISION (JUDICIAL REVIEW) ________ IN THE MATTER OF AN APPLICATION BY EDWARD BARNARD FOR JUDICIAL REVIEW OF THE DECISION BY CHIEF CONSTABLE OF THE POLICE SERVICE OF NORTHERN IRELAND ________ TREACY J INDEX Para Nos. Page No. Introduction ........................................................................................ [1] 2 Factual Background ........................................................................... [2] – [4] 2 - 3 The Investigation .............................................................................. [5] – [9] 3 - 4 The Set Up, Development and Eventual Disbandment of the HET ....................................................................................................... [10] – [15] 4 - 6 What was the HET? ........................................................................... [16] – [18] 6 - 12 Oversight of the Work of the HET .................................................. [19] 12 National Oversight Measures .......................................................... [20] – [25] 12 – 22 Oversight by the Committee of Ministers (“CM”) ...................... [26] – [28] 22 - 23 The Relationship of the HET with the Article 2 Procedural Duty ....................................................................................................... [29] – [32] 23 - 25 Structure -

The Path to Revolutionary Violence Within the Weather Underground and Provisional IRA

The Path to Revolutionary Violence within the Weather Underground and Provisional IRA Edward Moran HIS 492: Seminar in History December 17, 2019 Moran 1 The 1960’s was a decade defined by a spirit of activism and advocacy for change among oppressed populations worldwide. While the methods for enacting change varied across nations and peoples, early movements such as that for civil rights in America were often committed to peaceful modes of protest and passive resistance. However, the closing years of the decade and the dawn of the 1970’s saw the patterned global spread of increasingly militant tactics used in situations of political and social unrest. The Weather Underground Organization (WUO) in America and the Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA) in Ireland, two such paramilitaries, comprised young activists previously involved in the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and the Northern Irish Civil Rights Association (NICRA) respectively. What caused them to renounce the non-violent methods of the Students for a Democratic Society and the Northern Irish Civil Rights Association for the militant tactics of the Weather Underground and Irish Republican Army, respectively? An analysis of contemporary source materials, along with more recent scholarly works, reveals that violent state reactions to more passive forms of demonstration in the United States and Northern Ireland drove peaceful activists toward militancy. In the case of both the Weather Underground and the Provisional Irish Republican Army in the closing years of the 1960s and early years of the 1970s, the bulk of combatants were young people with previous experience in more peaceful campaigns for civil rights and social justice. -

Memory, Place and Gender: Armagh Stories: Voices from the Gaol Cahal Mclaughlin, Memory Studies Journal, September 2017

Memory, Place and Gender: Armagh Stories: Voices from the Gaol Cahal McLaughlin, Memory Studies Journal, September 2017. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1750698017730872 Abstract The film Armagh Stories: Voices from the Gaol (2015)1 is a documentary film edited from the Prisons Memory Archive2 and offers perspectives from those who passed through Armagh Gaol, which housed mostly female prisoners during the political conflict in and about Northern Ireland, known as the Troubles. Armagh Stories is an attempt to represent the experiences of prison staff, prisoners, tutors, a solicitor, chaplain and doctor in ways that are ethically inclusive and aesthetically relevant. By reflecting on the practice of participatory storytelling and its reception in a society transitioning out of violence, I investigate how memory, place and gender combine to suggest ways of addressing the legacy of a conflicted past in a contested present. Keywords documentary film, female, performing memory, prison, Troubles Introduction The Prisons Memory Archive (PMA) is a collection of 175 filmed interviews recorded inside Armagh Gaol in 2006 and the Maze and Long Kesh Prison in 2007 (Figures 1 and 2). The protocols3 of co-ownership, inclusivity and life storytelling underpinned both the original recordings and subsequent film outputs that include Jolene Mairs Dyer’s (2011)4 Unseen Women and Laura Aguiar’s We Were There (2014).5 Funding was secured from the Community Relations Council’s Media Fund in 2015 to edit a 1-hour documentary on Armagh Goal, and two editors were employed over a 6-month period to work with me acting as director. Among the possible themes that can be excavated from the PMA’s 300 hours of audiovisual material, it was felt that since the representation of women in the Troubles has been particularly downplayed, foregrounding their experiences could help rebalance what is publicly available. -

Dziadok Mikalai 1'St Year Student

EUROPEAN HUMANITIES UNIVERSITY Program «World Politics and economics» Dziadok Mikalai 1'st year student Essay Written assignment Course «International relations and governances» Course instructor Andrey Stiapanau Vilnius, 2016 The Troubles (Northern Ireland conflict 1969-1998) Plan Introduction 1. General outline of a conflict. 2. Approach, theory, level of analysis (providing framework). Providing the hypothesis 3. Major actors involved, definition of their priorities, preferences and interests. 4. Origins of the conflict (historical perspective), major actions timeline 5. Models of conflicts, explanations of its reasons 6. Proving the hypothesis 7. Conclusion Bibliography Introduction Northern Ireland conflict, called “the Troubles” was the most durable conflict in the Europe since WW2. Before War in Donbass (2014-present), which lead to 9,371 death up to June 3, 20161 it also can be called the bloodiest conflict, but unfortunately The Donbass War snatched from The Troubles “the victory palm” of this dreadful competition. The importance of this issue, however, is still essential and vital because of challenges Europe experience now. Both proxy war on Donbass and recent terrorist attacks had strained significantly the political atmosphere in Europe, showing that Europe is not safe anymore. In this conditions, it is necessary for us to try to assume, how far this insecurity and tensions might go and will the circumstances and the challenges of a international relations ignite the conflict in Northern Ireland again. It also makes sense for us to recognize that the Troubles was also a proxy war to a certain degree 23 Sources, used in this essay are mostly mass-media articles, human rights observers’ and international organizations reports, and surveys made by political scientists on this issue. -

DCU Business School

DCU Business School RESEARCH PAPER SERIES PAPER NO. 31 November 1997 ‘Ulster Like Israel Can Only Lose Once’: Ulster Unionism, Security and Citizenship, 1972-97 Mr. John Doyle DCU Business School ISSN 1393-290X ‘ULSTER LIKE ISRAEL CAN ONLY LOSE ONCE’: ULSTER UNIONISM, SECURITY AND CITIZENSHIP, 1972-97. 1 ‘R EBELS HAVE NO RIGHTS ’ INTRODUCTION The idea that unionist political elites perceive themselves as representing a community which is ‘under siege’ and that their ideology reflects this position is regularly repeated in the literature. 2 Unionists are not uncomfortable with this description. Dorothy Dunlop, for example, is certainly not the only unionist politician to have defended herself against accusations of having a siege mentality by countering that ‘we are indeed under siege in Ulster.’ 3 A Belfast Telegraph editorial in 1989 talks of a unionist community ‘which feels under siege, both politically and from terrorism.’ 4 Cedric Wilson UKUP member of the Northern Ireland Forum said ‘with regard to Mr. Mallon’s comments about Unionist’s being in trenches, I can think of no better place to be ... when people are coming at you with guns and bombs, the best place to be is in a trench. I make no apology for being in a trench’ 5. Yet despite this widespread use of the metaphor there have been few analyses of the specifics of unionism’s position on security, perhaps because the answers appear self-evident and the impact of unionists’ views on security on the prospects for a political settlement are not appreciated. 6 This paper examines how the position of unionist political elites on security affects and reflects their broader views on citizenship. -

S444-CAJ-Submission-To-ICCPR

CAJ’s Submission no. S444 CAJ’s Submission to the United Nations Human Rights Committee on the UK’s 7th Periodic Report under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) June 2015 2nd Floor, Sturgen Building Tel – 028 9031 6000 9-15 Queen Street Email – [email protected] Belfast BT1 6EA Web – www.caj.org.uk About CAJ The Committee on the Administration of Justice (CAJ) was established in 1981 and is an independent non-governmental organisation affiliated to the International Federation of Human Rights. CAJ takes no position on the constitutional status of Northern Ireland and is firmly opposed to the use of violence for political ends. Its membership is drawn from across the community. The Committee seeks to ensure the highest standards in the administration of justice in Northern Ireland by ensuring that the government complies with its responsibilities in international human rights law. The CAJ works closely with other domestic and international human rights groups such as Amnesty International, Human Rights First (formerly the Lawyers Committee for Human Rights) and Human Rights Watch and makes regular submissions to a number of United Nations and European bodies established to protect human rights. CAJ’s activities include - publishing reports, conducting research, holding conferences, campaigning locally and internationally, individual casework and providing legal advice. Its areas of work are extensive and include policing, emergency laws and the criminal justice system, equality and advocacy for a Bill of Rights. CAJ however would not be in a position to do any of this work, without the financial help of its funders, individual donors and charitable trusts (since CAJ does not take government funding). -

Over Ten Years of Cover-Ups Left Nineteen People Dead

Irelandclick.com January 22 2007 Site Search DailyIreland.com Advanced Home As of 11th April 2006, www.dailyireland.com, incorporating www.irelandclick.com is Registered with ABC ELECTRONIC (www.abce.org.uk) and supports industry agreed standards for website News traffic measurement Comment Sport Over ten years of cover-ups left nineteen Features people dead ------------------------- RUC’s Special Branch gave Mount Vernon UVF a licence to kill Lá North Belfast News ------------------------- By Ciaran Barnes Downloads 19/01/2007 ------------------------- Andersonstown News 17 January 1993, Sharon McKenna: Two former policemen claim Mark Haddock told them he shot Shraon Home McKenna dead at the house of an elderly Protestant friend on the Shore Road. News Jonty Brown and Trevor McIlwrath claim Special Branch blocked attempts Comment by them to charge the UVF men involved despite the detectives having the confession. Sport Features 24 February 1994, Sean McParland: Murdered by a UVF Special Branch agent from Newtownabbey nicknamed ------------------------- the Beast. The paramilitary is the current boss of the organisation in Southeast Antrim. North Belfast News No one has been charged with the killing. Home News 17 May 1994, Eamon Fox and Gary Convie: The Catholic builders were allegedly shot dead by Haddock as they worked on a building site in Tiger's Comment Bay. Despite admitting to Special Branch handlers that he was involved Haddock was never charged. Sport Features 17 June 1994, Cecil Dougherty and William Corrigan: The Protestant builders were shot dead in a hut on a construction site in Rathcoole. They ------------------------- were mistaken for Catholics. South Belfast News The killing was carried out by a paramilitary who was trying to wrest control of the Southeast Antrim UVF from Haddock, shooting the men while Home his boss was on holiday. -

'Drowning in Here in His Bloody Sea' : Exploring TV Cop Drama's

'Drowning in here in his bloody sea' : exploring TV cop drama's representations of the impact of stress in modern policing Cummins, ID and King, M http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10439463.2015.1112387 Title 'Drowning in here in his bloody sea' : exploring TV cop drama's representations of the impact of stress in modern policing Authors Cummins, ID and King, M Type Article URL This version is available at: http://usir.salford.ac.uk/id/eprint/38760/ Published Date 2015 USIR is a digital collection of the research output of the University of Salford. Where copyright permits, full text material held in the repository is made freely available online and can be read, downloaded and copied for non-commercial private study or research purposes. Please check the manuscript for any further copyright restrictions. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. Introduction The Criminal Justice System is a part of society that is both familiar and hidden. It is familiar in that a large part of daily news and television drama is devoted to it (Carrabine, 2008; Jewkes, 2011). It is hidden in the sense that the majority of the population have little, if any, direct contact with the Criminal Justice System, meaning that the media may be a major force in shaping their views on crime and policing (Carrabine, 2008). As Reiner (2000) notes, the debate about the relationship between the media, policing, and crime has been a key feature of wider societal concerns about crime since the establishment of the modern police force. -

Double Blind

Double Blind The untold story of how British intelligence infiltrated and undermined the IRA Matthew Teague, The Atlantic, April 2006 Issue https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2006/04/double-blind/304710/ I first met the man now called Kevin Fulton in London, on Platform 13 at Victoria Station. We almost missed each other in the crowd; he didn’t look at all like a terrorist. He stood with his feet together, a short and round man with a kind face, fair hair, and blue eyes. He might have been an Irish grammar-school teacher, not an IRA bomber or a British spy in hiding. Both of which he was. Fulton had agreed to meet only after an exchange of messages through an intermediary. Now, as we talked on the platform, he paced back and forth, scanning the faces of passersby. He checked the time, then checked it again. He spoke in an almost impenetrable brogue, and each time I leaned in to understand him, he leaned back, suspicious. He fidgeted with several mobile phones, one devoted to each of his lives. “I’m just cautious,” he said. He lives in London now, but his wife remains in Northern Ireland. He rarely goes out, for fear of bumping into the wrong person, and so leads a life of utter isolation, a forty-five-year-old man with a lot on his mind. During the next few months, Fulton and I met several times on Platform 13. Over time his jitters settled, his speech loosened, and his past tumbled out: his rise and fall in the Irish Republican Army, his deeds and misdeeds, his loyalties and betrayals. -

Sinn Féin Ard Fheis 2014 Dé Haoine 7Ú & Dé Sathairn 8Ú Feabhra, Loch Garman Friday 7Th & Saturday 8Th Febuary, Wexford Bí Le Shinn Féin / Join Sinn Féin

Clar 2014 Cover spread no spine 24/01/2014 11:36 Page 1 Sinn Féin Ard Fheis 2014 Dé hAoine 7ú & Dé Sathairn 8ú Feabhra, Loch Garman Friday 7th & Saturday 8th Febuary, Wexford Bí le Shinn Féin / Join Sinn Féin Bí le Téacs / Join by Text: Seol an focal SINN FEIN ansin d’ainm agus seoladh chuig / Text the word SINN FEIN followed by your name and address to: 51444 (26 Chondae / 26 counties) 60060 (6 Chondae / 6 counties) Ar Líne / Join online: www.sinnfein.ie/join-sinn-fein PUTTING IRELAND Sinn Féin Sinn Féin 44 Cearnóg Pharnell, 44 Parnell Square, Baile Átha Cliath 1, Éire. Dublin 1, Ireland. FIRST Tel: (353) 1 872 6100/872 6932 Tel: (353) 1 872 6100/872 6932 Fax: (353) 1 889 2566 Fax: (353) 1 889 2566 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] ÉIRE CHUN TOSAIGH Sinn Féin Sinn Féin 53 Bóthar na bhFál, 53 Falls Road, Béal Feirste, BT 12PD, Éire. Belfast, BT 12PD, Ireland. Tel: 028 90 347350 Tel: 028 90 347350 Fax: 028 90 347386 Fax: 028 90 347386 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] www.sinnfein.ie www.sinnfein.ie SFAF Clar 2014.qxd 24/01/2014 11:34 Page 1 Sinn Féin Ard Fheis 2014 Wexford Friday 7th February 16.00 » Registration 18.00 » David Cullinane Opening 18.15 » Economy • Decent Work for Decent Pay Motions 1-13 | Pages 5-8 • Reducing the Tax Burden on Ordinary Workers Motions 14-19 | Pages 8-10 • Protecting the Conditions of those in Work Motions 20-21 | Pages 10-11 • Economic Sovereignty Motions 22-25 | Pages 11-13 19.00 » Keynote Address from Martin McGuinness 19.15 » Peace Process • Dealing with the Legacy of