Born on One Side of Partition: Reassessing Lessons Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Partnership Panel Committee Report Submitted To: Council Meeting

Title of Report: Partnership Panel Committee Council Meeting Report Submitted To: Date of Meeting: 6 October 2020 For Decision or For Decision For Information Linkage to Council Strategy (2019-23) Strategic Theme Leader and Champion Outcome We will establish key relationships with Government, agencies and potential strategic partners in Northern Ireland and external to it which helps us to deliver our vision for this Council area. Lead Officer Director of Corporate Services Budgetary Considerations Cost of Proposal N/A Included in Current Year Estimates N/A Capital/Revenue N/A Code N/A Staffing Costs N/A Screening Required for new or revised Policies, Plans, Strategies or Service Delivery Requirements Proposals. Section 75 Screening Completed: Yes/No Date: Screening EQIA Required and Yes/No Date: Completed: Rural Needs Screening Completed Yes/No Date: Assessment (RNA) RNA Required and Yes/No Date: Completed: Data Protection Screening Completed: Yes/ No Date: Impact Assessment DPIA Required and Yes/No Date: (DPIA) Completed: 201006 – Partnership Panel Key Outcomes Note – Version No. 1 Page 1 of 2 1.0 Purpose of Report 1.1 The Purpose of the Report is to present the Key Outcomes Note from the Partnership Panel. 2.0 Background 2.1 The Northern Ireland Partnership Panel convened for the first time in four years on 16 September 2020. This Outcomes Note is provided by NILGA, the Northern Ireland Local Government Association, to provide an immediate update to all 11 member councils. Full Minutes will follow. 3.0 Recommendation(s) 3.1 It is recommended that Council note the Partnership Panel Key Outcomes Note, dated 16 September 2020. -

His Honour Judge Peter Smithwick for the Tribunal

A P P E A R A N C E S The Sole Member: His Honour Judge Peter Smithwick For the Tribunal: Mrs. Mary Laverty, SC Mr. Justin Dillon, SC Mr. Dara Hayes, BL Mr. Fintan Valentine, BL Instructed by: Jane McKevitt Solicitor For the Commissioner of An Garda Siochana: Mr. Diarmuid McGuinness, SC Mr. Michael Durack, SC Mr. Gareth Baker, BL Instructed by: Mary Cummins CSSO For Owen Corrigan: Mr. Jim O'Callaghan, SC Mr. Darren Lehane, BL Instructed by: Fintan Lawlor Lawlor Partners Solicitors For Leo Colton: Mr. Paul Callan, SC Mr. Eamon Coffey, BL Instructed by: Dermot Lavery Solicitors For Finbarr Hickey: Fionnuala O'Sullivan, BL Instructed by: James MacGuill & Co. For the Attorney General: Ms. Nuala Butler, SC Mr. Douglas Clarke, SC Instructed by: CSSO For Freddie Scappaticci: Eavanna Fitzgerald, BL Pauline O'Hare Instructed by: Michael Flanigan Solicitor For Kevin Fulton: Mr. Neil Rafferty, QC Instructed by: John McAtamney Solicitor For Breen Family: Mr. John McBurney For Buchanan Family/ Heather Currie: Ernie Waterworth McCartan Turkington Breen Solicitors For the PSNI: Mark Robinson, BL NOTICE: A WORD INDEX IS PROVIDED AT THE BACK OF THIS TRANSCRIPT. THIS IS A USEFUL INDEXING SYSTEM, WHICH ALLOWS YOU TO QUICKLY SEE THE WORDS USED IN THE TRANSCRIPT, WHERE THEY OCCUR AND HOW OFTEN. EXAMPLE: - DOYLE [2] 30:28 45:17 THE WORD “DOYLE” OCCURS TWICE PAGE 30, LINE 28 PAGE 45, LINE 17 I N D E X Witness Page No. Line No. OWEN CORRIGAN CROSS-EXAMINED BY MR. O'CALLAGHAN 4 1 Smithwick Tribunal - 1 August 2012 - Day 119 1 1 THE TRIBUNAL RESUMED ON THE 1ST AUGUST 2012 AS FOLLOWS: 2 3 MR. -

Identity, Authority and Myth-Making: Politically-Motivated Prisoners and the Use of Music During the Northern Irish Conflict, 1962 - 2000

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Queen Mary Research Online Identity, authority and myth-making: Politically-motivated prisoners and the use of music during the Northern Irish conflict, 1962 - 2000 Claire Alexandra Green Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 1 I, Claire Alexandra Green, confirm that the research included within this thesis is my own work or that where it has been carried out in collaboration with, or supported by others, that this is duly acknowledged below and my contribution indicated. Previously published material is also acknowledged below. I attest that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge break any UK law, infringe any third party’s copyright or other Intellectual Property Right, or contain any confidential material. I accept that the College has the right to use plagiarism detection software to check the electronic version of the thesis. I confirm that this thesis has not been previously submitted for the award of a degree by this or any other university. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. Signature: Date: 29/04/19 Details of collaboration and publications: ‘It’s All Over: Romantic Relationships, Endurance and Loyalty in the Songs of Northern Irish Politically-Motivated Prisoners’, Estudios Irlandeses, 14, 70-82. 2 Abstract. In this study I examine the use of music by and in relation to politically-motivated prisoners in Northern Ireland, from the mid-1960s until 2000. -

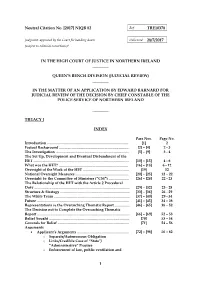

Barnard's (Edward) Application for Judicial Review of The

Neutral Citation No. [2017] NIQB 82 Ref: TRE10378 Judgment: approved by the Court for handing down Delivered: 28/7/2017 (subject to editorial corrections)* IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE IN NORTHERN IRELAND ________ QUEEN’S BENCH DIVISION (JUDICIAL REVIEW) ________ IN THE MATTER OF AN APPLICATION BY EDWARD BARNARD FOR JUDICIAL REVIEW OF THE DECISION BY CHIEF CONSTABLE OF THE POLICE SERVICE OF NORTHERN IRELAND ________ TREACY J INDEX Para Nos. Page No. Introduction ........................................................................................ [1] 2 Factual Background ........................................................................... [2] – [4] 2 - 3 The Investigation .............................................................................. [5] – [9] 3 - 4 The Set Up, Development and Eventual Disbandment of the HET ....................................................................................................... [10] – [15] 4 - 6 What was the HET? ........................................................................... [16] – [18] 6 - 12 Oversight of the Work of the HET .................................................. [19] 12 National Oversight Measures .......................................................... [20] – [25] 12 – 22 Oversight by the Committee of Ministers (“CM”) ...................... [26] – [28] 22 - 23 The Relationship of the HET with the Article 2 Procedural Duty ....................................................................................................... [29] – [32] 23 - 25 Structure -

Dziadok Mikalai 1'St Year Student

EUROPEAN HUMANITIES UNIVERSITY Program «World Politics and economics» Dziadok Mikalai 1'st year student Essay Written assignment Course «International relations and governances» Course instructor Andrey Stiapanau Vilnius, 2016 The Troubles (Northern Ireland conflict 1969-1998) Plan Introduction 1. General outline of a conflict. 2. Approach, theory, level of analysis (providing framework). Providing the hypothesis 3. Major actors involved, definition of their priorities, preferences and interests. 4. Origins of the conflict (historical perspective), major actions timeline 5. Models of conflicts, explanations of its reasons 6. Proving the hypothesis 7. Conclusion Bibliography Introduction Northern Ireland conflict, called “the Troubles” was the most durable conflict in the Europe since WW2. Before War in Donbass (2014-present), which lead to 9,371 death up to June 3, 20161 it also can be called the bloodiest conflict, but unfortunately The Donbass War snatched from The Troubles “the victory palm” of this dreadful competition. The importance of this issue, however, is still essential and vital because of challenges Europe experience now. Both proxy war on Donbass and recent terrorist attacks had strained significantly the political atmosphere in Europe, showing that Europe is not safe anymore. In this conditions, it is necessary for us to try to assume, how far this insecurity and tensions might go and will the circumstances and the challenges of a international relations ignite the conflict in Northern Ireland again. It also makes sense for us to recognize that the Troubles was also a proxy war to a certain degree 23 Sources, used in this essay are mostly mass-media articles, human rights observers’ and international organizations reports, and surveys made by political scientists on this issue. -

Catching Terrorists: the British System Versus the U.S

S. HRG. 109–701 CATCHING TERRORISTS: THE BRITISH SYSTEM VERSUS THE U.S. SYSTEM HEARING BEFORE A SUBCOMMITTEE OF THE COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED NINTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION SPECIAL HEARING SEPTEMBER 14, 2006—WASHINGTON, DC Printed for the use of the Committee on Appropriations ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.gpoaccess.gov/congress/index.html U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 30–707 PDF WASHINGTON : 2006 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi, Chairman TED STEVENS, Alaska ROBERT C. BYRD, West Virginia ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania DANIEL K. INOUYE, Hawaii PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico PATRICK J. LEAHY, Vermont CHRISTOPHER S. BOND, Missouri TOM HARKIN, Iowa MITCH MCCONNELL, Kentucky BARBARA A. MIKULSKI, Maryland CONRAD BURNS, Montana HARRY REID, Nevada RICHARD C. SHELBY, Alabama HERB KOHL, Wisconsin JUDD GREGG, New Hampshire PATTY MURRAY, Washington ROBERT F. BENNETT, Utah BYRON L. DORGAN, North Dakota LARRY CRAIG, Idaho DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas RICHARD J. DURBIN, Illinois MIKE DEWINE, Ohio TIM JOHNSON, South Dakota SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas MARY L. LANDRIEU, Louisiana WAYNE ALLARD, Colorado BRUCE EVANS, Staff Director TERRENCE E. SAUVAIN, Minority Staff Director SUBCOMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY JUDD GREGG, New Hampshire, Chairman THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi ROBERT C. BYRD, West Virginia TED STEVENS, Alaska DANIEL K. INOUYE, Hawaii ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania PATRICK J. LEAHY, Vermont PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico BARBARA A. -

Review of Martin J Mccleery, Operation Demetrius and Its Aftermath: a New History of the Use of Internment Without Trial in Northern Ireland 1971-75

Review of Martin J McCleery, Operation Demetrius and its Aftermath: A new History of the use of internment without trial in Northern Ireland 1971-75. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press, 2015. 202pp., £70 hard-cover. ISBN: 978-0-7190-9630-3. Reviewed by Dr Tony Craig, Staffordshire University, Stoke-on-Trent, UK In August 1971 the UK government, following a request made from the devolved government of Northern Ireland, authorised the re-introduction of internment without trial for suspected members of Irish Republican paramilitary groups in Northern Ireland. This new work, based on the author’s PhD thesis at Queen’s University Belfast, studies in detail the planning, implementation and impact of this counter-terrorism policy over the four years in which it was in place and represents the first monograph-length academic study of this particular aspect of the early period of the Northern Ireland Troubles. McCleery’s historical account measures contemporary and more recent analyses, against both government and accepted nationalist myths and narratives by carefully gauging its arguments against the evidence in a revealing and skilful way. The work is strongest in its discussions of the debates surrounding the internment policy’s introduction, the use of intelligence to identify suspects for the various lists that were developed and in the use of ‘enhanced’ interrogation techniques. McCleery’s work is especially useful in demonstrating the limitations of received wisdom taken from the post-facto accounts given by both the internees and the interners clarifying that, for example, whilst internment was used almost entirely against Irish Republican organisations, its targeting of those organisations was ultimately fairly accurate. -

Double Blind

Double Blind The untold story of how British intelligence infiltrated and undermined the IRA Matthew Teague, The Atlantic, April 2006 Issue https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2006/04/double-blind/304710/ I first met the man now called Kevin Fulton in London, on Platform 13 at Victoria Station. We almost missed each other in the crowd; he didn’t look at all like a terrorist. He stood with his feet together, a short and round man with a kind face, fair hair, and blue eyes. He might have been an Irish grammar-school teacher, not an IRA bomber or a British spy in hiding. Both of which he was. Fulton had agreed to meet only after an exchange of messages through an intermediary. Now, as we talked on the platform, he paced back and forth, scanning the faces of passersby. He checked the time, then checked it again. He spoke in an almost impenetrable brogue, and each time I leaned in to understand him, he leaned back, suspicious. He fidgeted with several mobile phones, one devoted to each of his lives. “I’m just cautious,” he said. He lives in London now, but his wife remains in Northern Ireland. He rarely goes out, for fear of bumping into the wrong person, and so leads a life of utter isolation, a forty-five-year-old man with a lot on his mind. During the next few months, Fulton and I met several times on Platform 13. Over time his jitters settled, his speech loosened, and his past tumbled out: his rise and fall in the Irish Republican Army, his deeds and misdeeds, his loyalties and betrayals. -

By James King B.A., Samford University, 2006 M.L.I.S., University

THE STRUGGLE CONTINUES: ARCHIVAL APPROACHES TO CIVIL RIGHTS IN NORTHERN IRELAND AND THE AMERICAN SOUTH by James King B.A., Samford University, 2006 M.L.I.S., University of Alabama, 2007 M.A., Boston College, 2009 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of School of Computing and Information in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2018 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH SCHOOL OF COMPUTING AND INFORMATION This dissertation was presented by James King It was defended on November 16, 2017 and approved by Dr. Sheila Corrall, Professor, Library and Information Science Dr. Andrew Flinn, Reader in Archival Studies and Oral History, Information Studies, University College London Dr. Alison Langmead, Associate Professor, Library and Information Science Dissertation Advisor: Dr. Richard J. Cox, Professor, Library and Information Science ii Copyright © by James King 2018 iii THE STRUGGLE CONTINUES: ARCHIVAL APPROACHES TO CIVIL RIGHTS IN NORTHERN IRELAND AND THE AMERICAN SOUTH James King, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2018 When police and counter-protesters broke up the first march of the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA) in August 1968, activists sang the African American spiritual, “We Shall Overcome” before disbanding. The spiritual, so closely associated with the earlier civil rights struggle in the United States, was indicative of the historical and material links shared by the movements in Northern Ireland and the American South. While these bonds have been well documented within history and media studies, the relationship between these regions’ archived materials and contemporary struggles remains largely unexplored. While some artifacts from the movements—along with the oral histories and other materials that came later—remained firmly ensconced within the archive, others have been digitally reformatted or otherwise repurposed for a range of educational, judicial, and social projects. -

Responsibilities of the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland

House of Commons Northern Ireland Affairs Committee Responsibilities of the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland Oral Evidence Wednesday 6 November 2013 Rt Hon Mrs Theresa Villiers MP, Secretary of State for Northern Ireland Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 6 November 2013 HC 798 Published on 23 December 2013 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £6.00 cobber Pack: U PL: COE1 [SO] Processed: [23-12-2013 07:30] Job: 035313 Unit: PG01 Source: /MILES/PKU/INPUT/035313/035313_o001_MP Corrected transcript SofS 06.11.13.xml Northern Ireland Committee: Evidence Ev 1 Oral evidence Taken before the Northern Ireland Affairs Committee on Wednesday 6 November 2013 Members present: Laurence Robertson (Chair) Mr David Anderson Kate Hoey Mr Joe Benton Nigel Mills Oliver Colvile Ian Paisley Mr Stephen Hepburn Andrew Percy Lady Hermon ________________ Examination of Witnesses Witnesses: Rt Hon Mrs Theresa Villiers MP, Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, Julian King, Director General, and Mark Larmour, Deputy Director, Northern Ireland Office, gave evidence. Q1 Chair: We will start the public session. start-up loans scheme, which has been highly Secretary of State, you are very welcome. Thank you successful in England and Wales, is now rolled out in very much for joining us. There is a range of issues Northern Ireland. The banking taskforce established we would like to discuss with you. Perhaps you would under the pact has started its work and was helpful like to introduce your team and make a brief opening in providing some input into the recent decision on statement. -

In Defense of Propaganda: the Republican Response to State

IN DEFENSE OF PROPAGANDA: THE REPUBLICAN RESPONSE TO STATE CREATED NARRATIVES WHICH SILENCED POLITICAL SPEECH DURING THE NORTHERN IRISH CONFLICT, 1968-1998 A thesis presented to The Honors Tutorial College Ohio University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation from the Honors Tutorial College with a Degree of Bachelor of Science in Journalism By Selina Nadeau April 2017 1 This thesis is approved by The Honors Tutorial College and the Department of Journalism Dr. Aimee Edmondson Professor, Journalism Thesis Adviser Dr. Bernhard Debatin Director of Studies, Journalism Dr. Jeremy Webster Dean, Honors Tutorial College 2 Table of Contents 1. History 2. Literature Review 2.1. Reframing the Conflict 2.2.Scholarship about Terrorism in Northern Ireland 2.3.Media Coverage of the Conflict 3. Theoretical Frameworks 3.1.Media Theory 3.2.Theories of Ethnic Identity and Conflict 3.3.Colonialism 3.4.Direct rule 3.5.British Counterterrorism 4. Research Methods 5. Researching the Troubles 5.1.A student walks down the Falls Road 6. Media Censorship during the Troubles 7. Finding Meaning in the Posters from the Troubles 7.1.Claims of Abuse of State Power 7.1.1. Social, political or economic grievances 7.1.2. Criticism of Government Officials 7.1.3. Criticism of the police, army or security forces 7.1.4. Criticism of media or censorship of media 7.2.Calls for Peace 7.2.1. Calls for inclusive all-party peace talks 7.2.2. British withdrawal as the solution 7.3.Appeals to Rights, Freedom, or Liberty 7.3.1. Demands of the Civil Rights Movement 7.3.2. -

THE APPARATUS of IMPUNITY? Human Rights Violations and the Northern Ireland Conflict: a Narrative of Official Limitations on Post-Agreement Investigative Mechanisms

THE APPARATUS OF IMPUNITY? Human rights violations and the Northern Ireland conflict: a narrative of official limitations on post-Agreement investigative mechanisms Committee on the Administration of Justice January 2015 The Apparatus of Impunity? Committee on the Administration of Justice (CAJ) © Committee on the Administration of Justice January 2015 The material may be reproduced, free of charge, in any format or medium without specific permission, provided the reproduction is not for financial or material gain.The material must be reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading context. If the material is to be republished or issued to others, acknowledgement must be given to its source, copyright status, and date of publication. This publication is available on our website. CAJ Committee on the Administration of Justice 2nd Floor, Sturgen Building 9-15 Queen Street Belfast BT1 6EA Tel: 028 9031 6000 Fax: 028 9031 4583 [email protected] www.caj.org.uk ISBN 978 1 873285 94 7 The Apparatus of Impunity? Committee on the Administration of Justice (CAJ) THE APPARATUS OF IMPUNITY? Human rights violations and the Northern Ireland conflict: a narrative of official limitations on post-Agreement investigative mechanisms Committee on the Administration of Justice January 2015 The Apparatus of Impunity? Committee on the Administration of Justice (CAJ) Recent comments from key Council of Europe and UN human rights bodies in relation to existing mechanisms investigating the conflict in Northern Ireland: The absence of any plausible explanation for the failure to collect key evidence at the time when this was possible, and for attempts to even obstruct this process, should be treated with particular vigilance.