'Drowning in Here in His Bloody Sea' : Exploring TV Cop Drama's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

City of Nampa Special City Council Meeting Budget Workshop Livestreaming at July 13, 2020 8:00 AM

City of Nampa Special City Council Meeting Budget Workshop Livestreaming at https://livestream.com/cityofnampa July 13, 2020 8:00 AM Call to Order Prayer Roll Call Opening Comments - Mayor Part I – Foundational review, Revenues & Budget Summary (Doug Racine) • Foundational Budget Discussion • Fiscal 2021 Budget Summary • Overall Budget Risks and Opportunities • Fund Budgets – Summarized review • General Government Summarized Budget Break Action Item: Council Discussion & Vote on FY2021 Budgets: Part II – Departmental Budgets, Capital Budgets, Grants & Position Control (Ed Karass) • Budget Development introduction (1) Departmental Budget Reviews 1-1. Clerks 1-2. Code Enforcement 1-3. Econ Development 1-4. Facilities 1-5. Finance 1-6. Legal 1-7. Workforce Development 1-8. IT 1-9. Mayor & City Council 1-10. General Government Lunch Break (1) Continued Review of Departmental Budget Reviews 1-11. Public Work Admin 1-12. Public Works Engineering 1-13. Fire 1-14. Police Page 1 of 3 City of Nampa Special City Council Meeting Budget Workshop Livestreaming at https://livestream.com/cityofnampa July 13, 2020 8:00 AM (2) Special Revenue, Enterprise & Internal Service Funds 2-0. 911 2-1. Civic Center/Ford Idaho Center 2-2. Family Justice Center 2-3. Library 2-4. Parks & Recs (Incl Golf) 2-5. Stormwater 2-6. Streets / Airport 2-6. Water / Irrigation 2-7. Wastewater 2-8. Environmental Compliance 2-9. Sanitation / Utility Billing Break (2) Continued Review of Special Revenue, Enterprise & Internal Service Funds 2-10. Building / Development Services 2-11. Planning & Zoning 2-12. Fleet (4) Grants (5) Impact Fees (6) Capital Budget Review 6-0. -

'Nothing but the Truth': Genre, Gender and Knowledge in the US

‘Nothing but the Truth’: Genre, Gender and Knowledge in the US Television Crime Drama 2005-2010 Hannah Ellison Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) University of East Anglia School of Film, Television and Media Studies Submitted January 2014 ©This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that no quotation from the thesis, nor any information derived therefrom, may be published without the author's prior, written consent. 2 | Page Hannah Ellison Abstract Over the five year period 2005-2010 the crime drama became one of the most produced genres on American prime-time television and also one of the most routinely ignored academically. This particular cyclical genre influx was notable for the resurgence and reformulating of the amateur sleuth; this time remerging as the gifted police consultant, a figure capable of insights that the police could not manage. I term these new shows ‘consultant procedurals’. Consequently, the genre moved away from dealing with the ills of society and instead focused on the mystery of crime. Refocusing the genre gave rise to new issues. Questions are raised about how knowledge is gained and who has the right to it. With the individual consultant spearheading criminal investigation, without official standing, the genre is re-inflected with issues around legitimacy and power. The genre also reengages with age-old questions about the role gender plays in the performance of investigation. With the aim of answering these questions one of the jobs of this thesis is to find a way of analysing genre that accounts for both its larger cyclical, shifting nature and its simultaneously rigid construction of particular conventions. -

Representations of British Probation

British Journal of Community Justice ©2012 Sheffield Hallam University, Sheffield ISSN 1475-0279 Vol. 10(2): 5-23 REPRESENTATIONS OF BRITISH PROBATION OFFICERS IN FILM, TELEVISION DRAMA AND NOVELS 1948-2012 Mike Nellis, Emeritus Professor of Criminal and Community Justice, School of Law, University of Strathclyde Abstract This paper offers an overview of representations of the British probation service in three fictional media over a sixty year period, up to the present time. While there were never as many, and they were never as renowned as representations of police, lawyers and doctors, there are arguably more than has generally been realised. Broadly speaking - although there have always been individual exceptions to general trends - there has been a shift from supportive and optimistic representations to cynical and disillusioned ones, in which the viability of showing care and compassion to offenders is questioned or mocked. This mirrors wider political attempts to change the traditionally welfare-oriented culture of the service to something more punitive. The somewhat random and intermittent production of probation novels, films and television series over the period in questions has had no discernible cumulative impact on public understanding of probation, and it is suggested that the relative absence of iconic media portrayals of its officers, comparable to those achieved in police, legal and medical fiction, has made it more difficult to sustain credible debates about rehabilitation in popular culture. Introduction One of the problems the Probation Service has is that it is not very photogenic. We live with an image driven media and society and unfortunately probation doesn’t present itself well, certainly on television. -

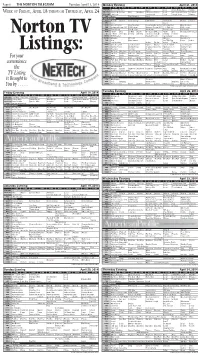

06 4-15-14 TV Guide.Indd

Page 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, April 15, 2014 Monday Evening April 21, 2014 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC Dancing With Stars Castle Local Jimmy Kimmel Live Nightline WEEK OF FRIDAY, APRIL 18 THROUGH THURSDAY, APRIL 24 KBSH/CBS 2 Broke G Friends Mike Big Bang NCIS: Los Angeles Local Late Show Letterman Ferguson KSNK/NBC The Voice The Blacklist Local Tonight Show Meyers FOX Bones The Following Local Cable Channels A&E Duck D. Duck D. Duck Dynasty Bates Motel Bates Motel Duck D. Duck D. AMC Jaws Jaws 2 ANIM River Monsters River Monsters Rocky Bounty Hunters River Monsters River Monsters CNN Anderson Cooper 360 CNN Tonight Anderson Cooper 360 E. B. OutFront CNN Tonight DISC Fast N' Loud Fast N' Loud Car Hoards Fast N' Loud Car Hoards DISN I Didn't Dog Liv-Mad. Austin Good Luck Win, Lose Austin Dog Good Luck Good Luck E! E! News The Fabul Chrisley Chrisley Secret Societies Of Chelsea E! News Norton TV ESPN MLB Baseball Baseball Tonight SportsCenter Olbermann ESPN2 NFL Live 30 for 30 NFL Live SportsCenter FAM Hop Who Framed The 700 Club Prince Prince FX Step Brothers Archer Archer Archer Tomcats HGTV Love It or List It Love It or List It Hunters Hunters Love It or List It Love It or List It HIST Swamp People Swamp People Down East Dickering America's Book Swamp People LIFE Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Listings: MTV Girl Code Girl Code 16 and Pregnant 16 and Pregnant House of Food 16 and Pregnant NICK Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Friends Friends Friends SCI Metal Metal Warehouse 13 Warehouse 13 Warehouse 13 Metal Metal For your SPIKE Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Jail Jail TBS Fam. -

A Sheffield Hallam University Thesis

Taboo : why are real-life British serial killers rarely represented on film? EARNSHAW, Antony Robert Available from the Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/20984/ A Sheffield Hallam University thesis This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Please visit http://shura.shu.ac.uk/20984/ and http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html for further details about copyright and re-use permissions. Taboo: Why are Real-Life British Serial Killers Rarely Represented on Film? Antony Robert Earnshaw Sheffield Hallam University MA English by Research September 2017 1 Abstract This thesis assesses changing British attitudes to the dramatisation of crimes committed by domestic serial killers and highlights the dearth of films made in this country on this subject. It discusses the notion of taboos and, using empirical and historical research, illustrates how filmmakers’ attempts to initiate productions have been vetoed by social, cultural and political sensitivities. Comparisons are drawn between the prevalence of such product in the United States and its uncommonness in Britain, emphasising the issues around the importing of similar foreign material for exhibition on British cinema screens and the importance of geographic distance to notions of appropriateness. The influence of the British Board of Film Classification (BBFC) is evaluated. This includes a focus on how a central BBFC policy – the so- called 30-year rule of refusing to classify dramatisations of ‘recent’ cases of factual crime – was scrapped and replaced with a case-by-case consideration that allowed for the accommodation of a specific film championing a message of tolerance. -

Transnational Television Drama Preliminary Programme 5-9 June 2018 Inclusive Pre-Conferences, Conference and Social Walks Programme

Transnational Television Drama Preliminary programme 5-9 June 2018 Inclusive pre-conferences, conference and social walks programme International Conference, 5-9 June 2018, Aarhus University, Denmark. Conference website: conferences.au.dk/transnationaltelevisiondrama2018 Venue: Building 5335, Katrinebjerg, Aarhus University, Helsingforsgade 14, 8200 Aarhus N. Tuesday 5 June 2018: Pre-conference dinner At your own costs, register online Time Event Venue 19.00 At a restaurant in the city centre (place tba) Wednesday 6 June 2018: Parallel pre-conference workshops Free event, register online Time Pre-conference Workshop Title & Lecturers: Hosts Venue 08.30 Welcome coffee/tea Outside 091 Audio-Visual Methodologies for Transnational Room 184 09.00- Workshop 1 Television Studies: What can the Video Essay Do for Assistant Professor Mathias Bonde Korsgaard 15.00 You? (AU, DK), Associate Professor Pia Majbritt Lecturers: Professor Cathrine Grant and Dr. Janet Jensen (AU, DK) McCabe, both Birkbeck, University of London, UK PhD networking and career planning. Room 091 09.00- PhD workshop 2 Lecturers: Professor Trine Syvertsen (University of Oslo, Cathrin Bengesser (Birkbeck, University of 15.30 N), Professor Lothar Mikos (Film University Potsdam, DE), London, UK), Associate Prof Susanne Eichner, PhD students Cathrin Bengesser (Birkbeck, University of (AU, DK). London, UK), Postdoc Pei Sze Chow (MSCA AU), Associate Prof Susanne Eichner, (AU, DK. 1 6-9 June 2018: International conference: Transnational Television Drama: Tastes, Travels and Trends Wednesday 6 June 2018: Trends: Production Perspectives 15.00 Registration, welcome coffee & tea Venue 16.00 Welcome 16.15 Industry panel Co-producing for international markets Peter Boegh Andersen Aud Panel: Olivier Bibas (tbc), producer, Atlantique Prodcution (F), Piv Bernth, producer, Apple Tree Productions (DK), Peter Bose (tbc), producer, Miso Film (DK). -

06 4-15 TV Guide.Indd 1 4/15/08 7:49:32 AM

PAGE 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, April 15, 2008 Monday Evening April 21, 2008 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC Dancing With the Stars Samantha Bachelor-Lond Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live WEEK OF FRIDAY , APRIL 18 THROUGH THURSDAY , APRIL 24 KBSH/CBS Big Bang How I Met Two Men Rules CSI: Miami Local Late Show-Letterman Late Late KSNK/NBC Deal or No Deal Medium Local Tonight Show Late FOX Bones House Local Cable Channels A&E Intervention Intervention I Survived Crime 360 Intervention AMC Ferris Bueller Teen Wolf StirCrazy ANIM Petfinder Animal Cops Houston Animal Precinct Petfinder Animal Cops Houston CNN CNN Election Center Larry King Live Anderson Cooper 360 Larry King Live DISC Dirty Jobs Dirty Jobs Verminators How-Made How-Made Dirty Jobs DISN Finding Nemo So Raven Life With The Suite Montana Replace Kim E! Keep Up Keep Up True Hollywood Story Girls Girls E! News Chelsea Daily 10 Girls ESPN MLB Baseball Baseball Tonight SportsCenter Fastbreak Baseball Norton TV ESPN2 Arena Football Football E:60 NASCAR Now FAM Greek America's Prom Queen Funniest Home Videos The 700 Club America's Prom Queen FX American History X '70s Show The Riches One Hour Photo HGTV To Sell Curb Potential Potential House House Buy Me Sleep To Sell Curb HIST Modern Marvels Underworld Ancient Discoveries Decoding the Past Modern Marvels LIFE Reba Reba Black and Blue Will Will The Big Match MTV True Life The Paper The Hills The Hills The Paper The Hills The Paper The Real World NICK SpongeBob Drake Home Imp. -

Cultural Representations of the Moors Murderers and Yorkshire Ripper Cases

CULTURAL REPRESENTATIONS OF THE MOORS MURDERERS AND YORKSHIRE RIPPER CASES by HENRIETTA PHILLIPA ANNE MALION PHILLIPS A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Modern Languages School of Languages, Cultures, Art History, and Music College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham October 2016 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract This thesis examines written, audio-visual and musical representations of real-life British serial killers Myra Hindley and Ian Brady (the ‘Moors Murderers’) and Peter Sutcliffe (the ‘Yorkshire Ripper’), from the time of their crimes to the present day, and their proliferation beyond the cases’ immediate historical-legal context. Through the theoretical construct ‘Northientalism’ I interrogate such representations’ replication and engagement of stereotypes and anxieties accruing to the figure of the white working- class ‘Northern’ subject in these cases, within a broader context of pre-existing historical trajectories and generic conventions of Northern and true crime representation. Interrogating changing perceptions of the cultural functions and meanings of murderers in late-capitalist socio-cultural history, I argue that the underlying structure of true crime is the counterbalance between the exceptional and the everyday, in service of which its second crucial structuring technique – the depiction of physical detail – operates. -

06 9/2 TV Guide.Indd 1 9/3/08 7:50:15 AM

PAGE 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, September 2, 2008 Monday Evening September 8, 2008 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC H.S. Musical CMA Music Festival Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live KBSH/CBS Big Bang How I Met Two Men Christine CSI: Miami Local Late Show-Letterman Late Late WEEK OF FRIDAY , SEPT . 5 THROUGH THUR S DAY , SEPT . 11 KSNK/NBC Deal or No Deal Toughest Jobs Dateline NBC Local Tonight Show Late FOX Sarah Connor Prison Break Local Cable Channels A&E Intervention Intervention After Paranorml Paranorml Paranorml Paranorml Intervention AMC Alexander Geronimo: An American Legend ANIM Animal Cops Houston Animal Cops Houston Miami Animal Police Miami Animal Police Animal Cops Houston CNN CNN Election Center Larry King Live Anderson Cooper 360 Larry King Live DISC Mega-Excavators 9/11 Towers Into the Unknown How-Made How-Made Mega-Excavators DISN An Extremely Goofy Movie Wizards Wizards Life With The Suite Montana So Raven Cory E! Cutest Child Stars Dr. 90210 E! News Chelsea Chelsea Girls ESPN NFL Football NFL Football ESPN2 Poker Series of Poker Baseball Tonight SportsCenter NASCAR Now Norton TV FAM Secret-Teen Secret-Teen Secret-Teen The 700 Club Whose? Whose? FX 13 Going on 30 Little Black Book HGTV To Sell Curb Potential Potential House House Buy Me Sleep To Sell Curb HIST The Kennedy Assassin 9/11 Conspiracies The Kennedy Assassin LIFE Army Wives Tell Me No Lies Will Will Frasier Frasier MTV Exposed Exposed Exiled The Hills The Hills Exiled The Hills Exiled Busted Busted NICK Pets SpongeBob Fam. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Benjamin F. Stickle Middle Tennessee State University Department of Criminal Justice Administration 1301 East Main Street - MTSU Box 238 Murfreesboro, Tennessee 37132 [email protected] www.benstickle.com (615) 898-2265 EDUCATION Doctor of Philosophy, 2015, Justice Administration University of Louisville, Louisville, Kentucky Master of Science, 2010, Justice Administration University of Louisville, Louisville, Kentucky Bachelor of Arts, 2005, Sociology Cedarville University, Cedarville, Ohio ACADEMIC POSITIONS Middle Tennessee State University, Department of Criminal Justice Administration 2019 – Present Associate Professor 2016 – 2019 Assistant Professor Campbellsville University, Department of Criminal Justice Administration 2014 – 2016 Assistant Professor 2011 – 2014 Instructor (Full-time) University of Louisville, Department of Justice Administration 2014 – 2015 Lecturer ADMINISTRATIVE POSITIONS Middle Tennessee State University, Department of Criminal Justice Administration 2018 – Present Coordinator, Online Bachelor of Criminal Justice Administration 2018 – Present Chair, Curriculum Committee Campbellsville University, Department of Criminal Justice Administration 2011-2016 Site Coordinator, Louisville Education Center PROFESSIONAL APPOINTMENTS & AFFILIATIONS 2019 – Present Affiliated Faculty, Political Economy Research Institute, Middle Tennessee State University 2017 – Present Senior Fellow for Criminal Justice, Beacon Center of Tennessee Ben Stickle CV, Page 2 AREAS OF SPECIALIZATION • Property Crime: Metal -

THE APPARATUS of IMPUNITY? Human Rights Violations and the Northern Ireland Conflict: a Narrative of Official Limitations on Post-Agreement Investigative Mechanisms

THE APPARATUS OF IMPUNITY? Human rights violations and the Northern Ireland conflict: a narrative of official limitations on post-Agreement investigative mechanisms Committee on the Administration of Justice January 2015 The Apparatus of Impunity? Committee on the Administration of Justice (CAJ) © Committee on the Administration of Justice January 2015 The material may be reproduced, free of charge, in any format or medium without specific permission, provided the reproduction is not for financial or material gain.The material must be reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading context. If the material is to be republished or issued to others, acknowledgement must be given to its source, copyright status, and date of publication. This publication is available on our website. CAJ Committee on the Administration of Justice 2nd Floor, Sturgen Building 9-15 Queen Street Belfast BT1 6EA Tel: 028 9031 6000 Fax: 028 9031 4583 [email protected] www.caj.org.uk ISBN 978 1 873285 94 7 The Apparatus of Impunity? Committee on the Administration of Justice (CAJ) THE APPARATUS OF IMPUNITY? Human rights violations and the Northern Ireland conflict: a narrative of official limitations on post-Agreement investigative mechanisms Committee on the Administration of Justice January 2015 The Apparatus of Impunity? Committee on the Administration of Justice (CAJ) Recent comments from key Council of Europe and UN human rights bodies in relation to existing mechanisms investigating the conflict in Northern Ireland: The absence of any plausible explanation for the failure to collect key evidence at the time when this was possible, and for attempts to even obstruct this process, should be treated with particular vigilance. -

A History of the University of Manchester Since 1951

Pullan2004jkt 10/2/03 2:43 PM Page 1 University ofManchester A history ofthe HIS IS THE SECOND VOLUME of a history of the University of Manchester since 1951. It spans seventeen critical years in T which public funding was contracting, student grants were diminishing, instructions from the government and the University Grants Commission were multiplying, and universities feared for their reputation in the public eye. It provides a frank account of the University’s struggle against these difficulties and its efforts to prove the value of university education to society and the economy. This volume describes and analyses not only academic developments and changes in the structure and finances of the University, but the opinions and social and political lives of the staff and their students as well. It also examines the controversies of the 1970s and 1980s over such issues as feminism, free speech, ethical investment, academic freedom and the quest for efficient management. The author draws on official records, staff and student newspapers, and personal interviews with people who experienced the University in very 1973–90 different ways. With its wide range of academic interests and large student population, the University of Manchester was the biggest unitary university in the country, and its history illustrates the problems faced by almost all British universities. The book will appeal to past and present staff of the University and its alumni, and to anyone interested in the debates surrounding higher with MicheleAbendstern Brian Pullan education in the late twentieth century. A history of the University of Manchester 1951–73 by Brian Pullan with Michele Abendstern is also available from Manchester University Press.