Gerry Adams Has Long Denied Being a Member of the I.R.A. but His Former Compatriots Say That He Authorized Murder. in the March

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John F. Morrison Phd Thesis

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by St Andrews Research Repository 'THE AFFIRMATION OF BEHAN?' AN UNDERSTANDING OF THE POLITICISATION PROCESS OF THE PROVISIONAL IRISH REPUBLICAN MOVEMENT THROUGH AN ORGANISATIONAL ANALYSIS OF SPLITS FROM 1969 TO 1997 John F. Morrison A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2010 Full metadata for this item is available in Research@StAndrews:FullText at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/3158 This item is protected by original copyright ‘The Affirmation of Behan?’ An Understanding of the Politicisation Process of the Provisional Irish Republican Movement Through an Organisational Analysis of Splits from 1969 to 1997. John F. Morrison School of International Relations Ph.D. 2010 SUBMISSION OF PHD AND MPHIL THESES REQUIRED DECLARATIONS 1. Candidate’s declarations: I, John F. Morrison, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 82,000 words in length, has been written by me, that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a research student in September 2005 and as a candidate for the degree of Ph.D. in May, 2007; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 2005 and 2010. Date 25-Aug-10 Signature of candidate 2. Supervisor’s declaration: I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of Ph.D. -

The Counter-Aesthetics of Republican Prison Writing

Notes Chapter One Introduction: Taoibh Amuigh agus Faoi Ghlas: The Counter-aesthetics of Republican Prison Writing 1. Gerry Adams, “The Fire,” Cage Eleven (Dingle: Brandon, 1990) 37. 2. Ibid., 46. 3. Pat Magee, Gangsters or Guerillas? (Belfast: Beyond the Pale, 2001) v. 4. David Pierce, ed., Introduction, Irish Writing in the Twentieth Century: A Reader (Cork: Cork University Press, 2000) xl. 5. Ibid. 6. Shiela Roberts, “South African Prison Literature,” Ariel 16.2 (Apr. 1985): 61. 7. Michel Foucault, “Power and Strategies,” Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972–1977, ed. Colin Gordon (New York: Pantheon, 1980) 141–2. 8. In “The Eye of Power,” for instance, Foucault argues, “The tendency of Bentham’s thought [in designing prisons such as the famed Panopticon] is archaic in the importance it gives to the gaze.” In Power/ Knowledge 160. 9. Breyten Breytenbach, The True Confessions of an Albino Terrorist (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1983) 147. 10. Ioan Davies, Writers in Prison (Cambridge, MA: Blackwell, 1990) 4. 11. Ibid. 12. William Wordsworth, “Preface to Lyrical Ballads,” The Norton Anthology of English Literature vol. 2A, 7th edition, ed. M. H. Abrams et al. (New York: W. W. Norton, 2000) 250. 13. Gerry Adams, “Inside Story,” Republican News 16 Aug. 1975: 6. 14. Gerry Adams, “Cage Eleven,” Cage Eleven (Dingle: Brandon, 1990) 20. 15. Wordsworth, “Preface” 249. 16. Ibid., 250. 17. Ibid. 18. Terry Eagleton, The Ideology of the Aesthetic (Cambridge, MA: Blackwell, 1990) 27. 19. W. B. Yeats, Essays and Introductions (New York: Macmillan, 1961) 521–2. 20. Bobby Sands, One Day in My Life (Dublin and Cork: Mercier, 1983) 98. -

King's Research Portal

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by King's Research Portal King’s Research Portal DOI: 10.1080/1057610X.2017.1283195 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Woodford, I., & Smith, M. L. R. (2017). The Political Economy of the Provos: Inside the Finances of the Provisional IRA – A Revision. STUDIES IN CONFLICT AND TERRORISM. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2017.1283195 Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

Identity, Authority and Myth-Making: Politically-Motivated Prisoners and the Use of Music During the Northern Irish Conflict, 1962 - 2000

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Queen Mary Research Online Identity, authority and myth-making: Politically-motivated prisoners and the use of music during the Northern Irish conflict, 1962 - 2000 Claire Alexandra Green Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 1 I, Claire Alexandra Green, confirm that the research included within this thesis is my own work or that where it has been carried out in collaboration with, or supported by others, that this is duly acknowledged below and my contribution indicated. Previously published material is also acknowledged below. I attest that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge break any UK law, infringe any third party’s copyright or other Intellectual Property Right, or contain any confidential material. I accept that the College has the right to use plagiarism detection software to check the electronic version of the thesis. I confirm that this thesis has not been previously submitted for the award of a degree by this or any other university. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. Signature: Date: 29/04/19 Details of collaboration and publications: ‘It’s All Over: Romantic Relationships, Endurance and Loyalty in the Songs of Northern Irish Politically-Motivated Prisoners’, Estudios Irlandeses, 14, 70-82. 2 Abstract. In this study I examine the use of music by and in relation to politically-motivated prisoners in Northern Ireland, from the mid-1960s until 2000. -

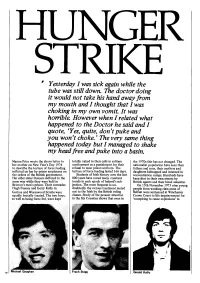

Article on Hungerstrike

" Yesterday I was sick again while the tube was still down. The doctor doing it would not take his hand away [rom my mouth and I thought that I was choking in my own vomit. It was homble. However when I related what happened to the Doctor he said and I quote, 'Yes, quite, don'tpuke and you won't choke. ' The very same thing happened today but I managed to shake my head [ree and puke into a basin. Marian Price wrote the above letter to totaHy naked in their ceHs in solitary the 1970s this has not changed. The her mother on New Year's Day 1974 confinement as a punishment for their nationalist population have seen their to describe the torture of force feeding refusal to wear prison uniform. The fathers and sons, their mothers and inflicted on her by prison employees on torture of force feeding lasted 166 days. daughters kidnapped and interned in the orders of the British government. Students of Irish history over the last concentration camps. Hundreds have Her eIder sister Dolours suffered in the 800 years have noted many constant been shot in their own streets by same way while they were held in trends in each epoch of Ireland's sub• British agents and their hired assassins. Brixton's men's prison. Their comrades jection. The most frequent is un• On 15th November 1973 nine young Hugh Feeney and Gerry KeHy in doubtedly the vicious treatment meted people from working class areas of Gartree and Wormwood Scrubs were out to the Irish by the British ruling Belfast were sentenced at Winchester equally brutally treated. -

These Are the Future Leaders of Ulster If the St Andrews Agreement Is Endorsed

The Burning Bush—Online article archive These are the future leaders of Ulster if the St Andrews Agreement is endorsed “The Burning Bush” has only two more issues to go after this current edition, before its witness concludes. It has sought to warn its readers of the wickedness and com- promise taking place within “church and state”, since its first edition back in March 1970. The issues facing Christians were comparatively plain and simple back then, or so it seems now on reflection. Today, however, the confusion that we sought to combat McGuinness (far right) in IRA uniform at the funeral of fellow within the ranks of the ecumenical churches and organi- IRA man and close friend Colm sations, seems to have spread to the ranks of those who, Keenan in 1972 over the years, have been engaged in opposing the reli- gious and political sell-out. The reaction to the St Andrews Agreement has shown that to be so. It is an agreement, when stripped of all its legal jargon and political frills, that will place an unrepentant murderer in co-leadership of Northern Ireland. How unthinkable such a notion was back in 1970! Today we are told, it is both thinkable and exceeding wise! In an effort to refocus the minds and hearts of Christians we publish some well- established facts about those whom the St Andrews Agreement would have us choose and submit to and make masters of our destiny and that of our children. By the blessing of God, may a consideration of these facts awaken the slumbering soul of Ulster Protestantism. -

Gerry Adams Comments on the Attack in Antrim : Sinn Féin

Gerry Adams comments on the attack in Antrim : Sinn Féin Friday, March 13, 2009 News Feed Comments ● Home ● About ❍ Note about this website ❍ Contact Us ❍ Representatives ❍ Leadership ❍ History ❍ Links ● Ard Fheis 2009 ❍ Clár and Motions ❍ Gerry Adams’ Presidential Address ❍ Martin McGuinness Keynote Speech on Irish Unity ❍ Keynote Economic Address - Mary Lou McDonald MEP ❍ Pat Doherty MP - Opening Address ❍ Gerry Kelly on Justice ❍ Pádraig Mac Lochlainn North West EU Candidate Lisbon Speech ❍ Minister for Agriculture & Rural Development Michelle Gildernew MP ❍ Bairbre de Brún MEP –EU Affairs ● Issues ❍ Irish Unity ❍ Economy ❍ Education ❍ Environment ❍ EU Affairs ❍ Health ❍ Housing ❍ International Affairs http://www.ardfheis.com/?p=628 (1 of 11)13/03/2009 10:19:18 Gerry Adams comments on the attack in Antrim : Sinn Féin ❍ Irish Language & Culture ❍ Justice & the Community ❍ Rural Regeneration ❍ Social Inclusion ❍ Women’s Rights ● Help/Join ❍ Help Sinn Féin ❍ Join Sinn Féin ❍ Friends of Sinn Féin ❍ Cairde Sinn Féin ● Donate ● Social Networks ● Campaign Literature ● Featured Stories ● Gerry Adams Blog ● Latest News ● Photo Gallery ● Speeches Ard Fheis '09 ● Videos ❍ Ard Fheis Videos Browse > Home / Featured Stories / Gerry Adams comments on the attack in Antrim Gerry Adams comments on the attack in Antrim March 10, 2009 by admin Filed under Featured Stories Leave a comment Gerry Adams statement in the Assembly Monday March 9, 2009 http://www.ardfheis.com/?p=628 (2 of 11)13/03/2009 10:19:18 Gerry Adams comments on the attack in Antrim : Sinn Féin —————————————————————————— http://www.ardfheis.com/?p=628 (3 of 11)13/03/2009 10:19:18 Gerry Adams comments on the attack in Antrim : Sinn Féin Gerry Adams Blog Monday March 9th, 2009 The only way to go is forward On Saturday night I was in County Clare. -

The Path to Revolutionary Violence Within the Weather Underground and Provisional IRA

The Path to Revolutionary Violence within the Weather Underground and Provisional IRA Edward Moran HIS 492: Seminar in History December 17, 2019 Moran 1 The 1960’s was a decade defined by a spirit of activism and advocacy for change among oppressed populations worldwide. While the methods for enacting change varied across nations and peoples, early movements such as that for civil rights in America were often committed to peaceful modes of protest and passive resistance. However, the closing years of the decade and the dawn of the 1970’s saw the patterned global spread of increasingly militant tactics used in situations of political and social unrest. The Weather Underground Organization (WUO) in America and the Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA) in Ireland, two such paramilitaries, comprised young activists previously involved in the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and the Northern Irish Civil Rights Association (NICRA) respectively. What caused them to renounce the non-violent methods of the Students for a Democratic Society and the Northern Irish Civil Rights Association for the militant tactics of the Weather Underground and Irish Republican Army, respectively? An analysis of contemporary source materials, along with more recent scholarly works, reveals that violent state reactions to more passive forms of demonstration in the United States and Northern Ireland drove peaceful activists toward militancy. In the case of both the Weather Underground and the Provisional Irish Republican Army in the closing years of the 1960s and early years of the 1970s, the bulk of combatants were young people with previous experience in more peaceful campaigns for civil rights and social justice. -

La Mon Atrocity Remembered a Memorial Service Has Been Held In

::: u.tv ::: NEWS Body found at Grand Canal SUNDAY Confidential files found at roadside 17/02/2008 18:05:01 Jobs boost for Cork Two 'critical' after attack La Mon atrocity remembered War of words 09:39 A memorial service has been held in Belfast to 09:20 New crime crackdown launched mark the 30th anniversary of the La Mon hotel Atrocity is remembered Man held after 'sex attack' bombing. La Mon atrocity remembered Relatives of the 12 people killed in the 1978 IRA atrocity gathered at Two held after Moira assault Castlereagh Council offices this afternoon for a service of remembrance Three held after drugs find led by the Rev David McIlveen. Limavady fire is 'suspicious' Man dies after Galway crash The DUP`s Irish Robinson and Jimmy Spratt were also among those Brendan Hughes has died attending the service today. Petrol bomb attack in Cullybackey Charge after Belfast death Disruption to Dublin Airport flights The event follows criticism of the DUP from some of the La Mon families who have accused Ian Paisley of letting victims down by going into Cannabis seeds found in Moy government with Sinn Fein. Man dies after Carlow RTC Charges after Portadown attack Two held after drugs seizure More than 400 people were attending a dinner dance in La Mon, when the IRA incendiary device went off. Man stabbed in Sligo Man 'critical' after Dublin assault Bluetongue confirmed in NI A wreath was laid at the La Mon garden in the council grounds today in Donegal murder victim laid to rest memory of the seven women and five men who were killed in one of the worst attacks of the Troubles. -

Challenging the People, the State and the Patriarchy in 1980S Irish Theatre

Provided by the author(s) and NUI Galway in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite the published version when available. Title Provoking performance: challenging the people, the state and the patriarchy in 1980s Irish Theatre Author(s) O'Beirne, Patricia Publication Date 2018-08-28 Publisher NUI Galway Item record http://hdl.handle.net/10379/14942 Downloaded 2021-09-27T14:54:59Z Some rights reserved. For more information, please see the item record link above. Provoking Performance: Challenging the People, the State and the Patriarchy in 1980s Irish Theatre Candidate: Patricia O’Beirne Supervisor: Dr. Ian Walsh School: School of Humanities Discipline: Drama and Theatre Studies Institution: National University of Ireland, Galway Submission Date: August 2018 Summary of Contents: Provoking Performance: Challenging the People, the State and the Patriarchy in 1980s Irish Theatre This thesis offers new perspectives and knowledge to the discipline of Irish theatre studies and historiography and addresses an overlooked period of Irish theatre. It aims to investigate playwriting and theatre-making in the Republic of Ireland during the 1980s. Theatre’s response to failures of the Irish state, to the civil war in Northern Ireland, and to feminist and working-class concerns are explored in this thesis; it is as much an exploration of the 1980s as it is of plays and playwrights during the decade. As identified by a literature review, scholarly and critical attention during the 1980s was drawn towards Northern Ireland where playwrights were engaging directly with the conflict in Northern Ireland. This means that proportionally the work of many playwrights in the Republic remains unexamined and unpublished. -

In Defense of Propaganda: the Republican Response to State

IN DEFENSE OF PROPAGANDA: THE REPUBLICAN RESPONSE TO STATE CREATED NARRATIVES WHICH SILENCED POLITICAL SPEECH DURING THE NORTHERN IRISH CONFLICT, 1968-1998 A thesis presented to The Honors Tutorial College Ohio University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation from the Honors Tutorial College with a Degree of Bachelor of Science in Journalism By Selina Nadeau April 2017 1 This thesis is approved by The Honors Tutorial College and the Department of Journalism Dr. Aimee Edmondson Professor, Journalism Thesis Adviser Dr. Bernhard Debatin Director of Studies, Journalism Dr. Jeremy Webster Dean, Honors Tutorial College 2 Table of Contents 1. History 2. Literature Review 2.1. Reframing the Conflict 2.2.Scholarship about Terrorism in Northern Ireland 2.3.Media Coverage of the Conflict 3. Theoretical Frameworks 3.1.Media Theory 3.2.Theories of Ethnic Identity and Conflict 3.3.Colonialism 3.4.Direct rule 3.5.British Counterterrorism 4. Research Methods 5. Researching the Troubles 5.1.A student walks down the Falls Road 6. Media Censorship during the Troubles 7. Finding Meaning in the Posters from the Troubles 7.1.Claims of Abuse of State Power 7.1.1. Social, political or economic grievances 7.1.2. Criticism of Government Officials 7.1.3. Criticism of the police, army or security forces 7.1.4. Criticism of media or censorship of media 7.2.Calls for Peace 7.2.1. Calls for inclusive all-party peace talks 7.2.2. British withdrawal as the solution 7.3.Appeals to Rights, Freedom, or Liberty 7.3.1. Demands of the Civil Rights Movement 7.3.2. -

Appendix List of Interviews*

Appendix List of Interviews* Name Date Personal Interview No. 1 29 August 2000 Personal Interview No. 2 12 September 2000 Personal Interview No. 3 18 September 2000 Personal Interview No. 4 6 October 2000 Personal Interview No. 5 16 October 2000 Personal Interview No. 6 17 October 2000 Personal Interview No. 7 18 October 2000 Personal Interview No. 8: Oonagh Marron (A) 17 October 2000 Personal Interview No. 9: Oonagh Marron (B) 23 October 2000 Personal Interview No. 10: Helena Schlindwein 28 October 2000 Personal Interview No. 11 30 October 2000 Personal Interview No. 12 1 November 2000 Personal Interview No. 13 1 November 2000 Personal Interview No. 14: Claire Hackett 7 November 2000 Personal Interview No. 15: Meta Auden 15 November 2000 Personal Interview No. 16 1 June 2000 Personal Interview Maggie Feeley 30 August 2005 Personal Interview No. 18 4 August 2009 Personal Interview No. 19: Marie Mulholland 27 August 2009 Personal Interview No. 20 3 February 2010 Personal Interview No. 21A (joint interview) 23 February 2010 Personal Interview No. 21B (joint interview) 23 February 2010 * Locations are omitted from this list so as to preserve the identity of the respondents. 203 Notes 1 Introduction: Rethinking Women and Nationalism 1 . I will return to this argument in a subsequent section dedicated to women’s victimisation as ‘women as reproducers’ of the nation. See also, Beverly Allen, Rape Warfare: The Hidden Genocide in Bosnia-Herzegovina (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 1996); Alexandra Stiglmayer, (ed.), Mass Rape: The War Against Women in Bosnia- Herzegovina (Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 1994); Carolyn Nordstrom, Fieldwork Under Fire: Contemporary Studies of Violence and Survival (Berkeley: University of California, 1995); Jill Benderly, ‘Rape, feminism, and nationalism in the war in Yugoslav successor states’ in Lois West, ed., Feminist Nationalism (London and New Tork: Routledge, 1997); Cynthia Enloe, ‘When soldiers rape’ in Maneuvers: The International Politics of Militarizing Women’s Lives (Berkeley: University of California, 2000).