“To the Extent the Law Allows:” Lessons from the Boston College Subpoenas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

King's Research Portal

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by King's Research Portal King’s Research Portal DOI: 10.1080/1057610X.2017.1283195 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Woodford, I., & Smith, M. L. R. (2017). The Political Economy of the Provos: Inside the Finances of the Provisional IRA – A Revision. STUDIES IN CONFLICT AND TERRORISM. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2017.1283195 Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

Identity, Authority and Myth-Making: Politically-Motivated Prisoners and the Use of Music During the Northern Irish Conflict, 1962 - 2000

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Queen Mary Research Online Identity, authority and myth-making: Politically-motivated prisoners and the use of music during the Northern Irish conflict, 1962 - 2000 Claire Alexandra Green Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 1 I, Claire Alexandra Green, confirm that the research included within this thesis is my own work or that where it has been carried out in collaboration with, or supported by others, that this is duly acknowledged below and my contribution indicated. Previously published material is also acknowledged below. I attest that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge break any UK law, infringe any third party’s copyright or other Intellectual Property Right, or contain any confidential material. I accept that the College has the right to use plagiarism detection software to check the electronic version of the thesis. I confirm that this thesis has not been previously submitted for the award of a degree by this or any other university. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. Signature: Date: 29/04/19 Details of collaboration and publications: ‘It’s All Over: Romantic Relationships, Endurance and Loyalty in the Songs of Northern Irish Politically-Motivated Prisoners’, Estudios Irlandeses, 14, 70-82. 2 Abstract. In this study I examine the use of music by and in relation to politically-motivated prisoners in Northern Ireland, from the mid-1960s until 2000. -

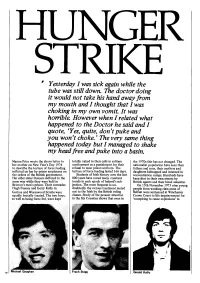

Article on Hungerstrike

" Yesterday I was sick again while the tube was still down. The doctor doing it would not take his hand away [rom my mouth and I thought that I was choking in my own vomit. It was homble. However when I related what happened to the Doctor he said and I quote, 'Yes, quite, don'tpuke and you won't choke. ' The very same thing happened today but I managed to shake my head [ree and puke into a basin. Marian Price wrote the above letter to totaHy naked in their ceHs in solitary the 1970s this has not changed. The her mother on New Year's Day 1974 confinement as a punishment for their nationalist population have seen their to describe the torture of force feeding refusal to wear prison uniform. The fathers and sons, their mothers and inflicted on her by prison employees on torture of force feeding lasted 166 days. daughters kidnapped and interned in the orders of the British government. Students of Irish history over the last concentration camps. Hundreds have Her eIder sister Dolours suffered in the 800 years have noted many constant been shot in their own streets by same way while they were held in trends in each epoch of Ireland's sub• British agents and their hired assassins. Brixton's men's prison. Their comrades jection. The most frequent is un• On 15th November 1973 nine young Hugh Feeney and Gerry KeHy in doubtedly the vicious treatment meted people from working class areas of Gartree and Wormwood Scrubs were out to the Irish by the British ruling Belfast were sentenced at Winchester equally brutally treated. -

The Path to Revolutionary Violence Within the Weather Underground and Provisional IRA

The Path to Revolutionary Violence within the Weather Underground and Provisional IRA Edward Moran HIS 492: Seminar in History December 17, 2019 Moran 1 The 1960’s was a decade defined by a spirit of activism and advocacy for change among oppressed populations worldwide. While the methods for enacting change varied across nations and peoples, early movements such as that for civil rights in America were often committed to peaceful modes of protest and passive resistance. However, the closing years of the decade and the dawn of the 1970’s saw the patterned global spread of increasingly militant tactics used in situations of political and social unrest. The Weather Underground Organization (WUO) in America and the Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA) in Ireland, two such paramilitaries, comprised young activists previously involved in the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and the Northern Irish Civil Rights Association (NICRA) respectively. What caused them to renounce the non-violent methods of the Students for a Democratic Society and the Northern Irish Civil Rights Association for the militant tactics of the Weather Underground and Irish Republican Army, respectively? An analysis of contemporary source materials, along with more recent scholarly works, reveals that violent state reactions to more passive forms of demonstration in the United States and Northern Ireland drove peaceful activists toward militancy. In the case of both the Weather Underground and the Provisional Irish Republican Army in the closing years of the 1960s and early years of the 1970s, the bulk of combatants were young people with previous experience in more peaceful campaigns for civil rights and social justice. -

La Mon Atrocity Remembered a Memorial Service Has Been Held In

::: u.tv ::: NEWS Body found at Grand Canal SUNDAY Confidential files found at roadside 17/02/2008 18:05:01 Jobs boost for Cork Two 'critical' after attack La Mon atrocity remembered War of words 09:39 A memorial service has been held in Belfast to 09:20 New crime crackdown launched mark the 30th anniversary of the La Mon hotel Atrocity is remembered Man held after 'sex attack' bombing. La Mon atrocity remembered Relatives of the 12 people killed in the 1978 IRA atrocity gathered at Two held after Moira assault Castlereagh Council offices this afternoon for a service of remembrance Three held after drugs find led by the Rev David McIlveen. Limavady fire is 'suspicious' Man dies after Galway crash The DUP`s Irish Robinson and Jimmy Spratt were also among those Brendan Hughes has died attending the service today. Petrol bomb attack in Cullybackey Charge after Belfast death Disruption to Dublin Airport flights The event follows criticism of the DUP from some of the La Mon families who have accused Ian Paisley of letting victims down by going into Cannabis seeds found in Moy government with Sinn Fein. Man dies after Carlow RTC Charges after Portadown attack Two held after drugs seizure More than 400 people were attending a dinner dance in La Mon, when the IRA incendiary device went off. Man stabbed in Sligo Man 'critical' after Dublin assault Bluetongue confirmed in NI A wreath was laid at the La Mon garden in the council grounds today in Donegal murder victim laid to rest memory of the seven women and five men who were killed in one of the worst attacks of the Troubles. -

Challenging the People, the State and the Patriarchy in 1980S Irish Theatre

Provided by the author(s) and NUI Galway in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite the published version when available. Title Provoking performance: challenging the people, the state and the patriarchy in 1980s Irish Theatre Author(s) O'Beirne, Patricia Publication Date 2018-08-28 Publisher NUI Galway Item record http://hdl.handle.net/10379/14942 Downloaded 2021-09-27T14:54:59Z Some rights reserved. For more information, please see the item record link above. Provoking Performance: Challenging the People, the State and the Patriarchy in 1980s Irish Theatre Candidate: Patricia O’Beirne Supervisor: Dr. Ian Walsh School: School of Humanities Discipline: Drama and Theatre Studies Institution: National University of Ireland, Galway Submission Date: August 2018 Summary of Contents: Provoking Performance: Challenging the People, the State and the Patriarchy in 1980s Irish Theatre This thesis offers new perspectives and knowledge to the discipline of Irish theatre studies and historiography and addresses an overlooked period of Irish theatre. It aims to investigate playwriting and theatre-making in the Republic of Ireland during the 1980s. Theatre’s response to failures of the Irish state, to the civil war in Northern Ireland, and to feminist and working-class concerns are explored in this thesis; it is as much an exploration of the 1980s as it is of plays and playwrights during the decade. As identified by a literature review, scholarly and critical attention during the 1980s was drawn towards Northern Ireland where playwrights were engaging directly with the conflict in Northern Ireland. This means that proportionally the work of many playwrights in the Republic remains unexamined and unpublished. -

In Defense of Propaganda: the Republican Response to State

IN DEFENSE OF PROPAGANDA: THE REPUBLICAN RESPONSE TO STATE CREATED NARRATIVES WHICH SILENCED POLITICAL SPEECH DURING THE NORTHERN IRISH CONFLICT, 1968-1998 A thesis presented to The Honors Tutorial College Ohio University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation from the Honors Tutorial College with a Degree of Bachelor of Science in Journalism By Selina Nadeau April 2017 1 This thesis is approved by The Honors Tutorial College and the Department of Journalism Dr. Aimee Edmondson Professor, Journalism Thesis Adviser Dr. Bernhard Debatin Director of Studies, Journalism Dr. Jeremy Webster Dean, Honors Tutorial College 2 Table of Contents 1. History 2. Literature Review 2.1. Reframing the Conflict 2.2.Scholarship about Terrorism in Northern Ireland 2.3.Media Coverage of the Conflict 3. Theoretical Frameworks 3.1.Media Theory 3.2.Theories of Ethnic Identity and Conflict 3.3.Colonialism 3.4.Direct rule 3.5.British Counterterrorism 4. Research Methods 5. Researching the Troubles 5.1.A student walks down the Falls Road 6. Media Censorship during the Troubles 7. Finding Meaning in the Posters from the Troubles 7.1.Claims of Abuse of State Power 7.1.1. Social, political or economic grievances 7.1.2. Criticism of Government Officials 7.1.3. Criticism of the police, army or security forces 7.1.4. Criticism of media or censorship of media 7.2.Calls for Peace 7.2.1. Calls for inclusive all-party peace talks 7.2.2. British withdrawal as the solution 7.3.Appeals to Rights, Freedom, or Liberty 7.3.1. Demands of the Civil Rights Movement 7.3.2. -

Appendix List of Interviews*

Appendix List of Interviews* Name Date Personal Interview No. 1 29 August 2000 Personal Interview No. 2 12 September 2000 Personal Interview No. 3 18 September 2000 Personal Interview No. 4 6 October 2000 Personal Interview No. 5 16 October 2000 Personal Interview No. 6 17 October 2000 Personal Interview No. 7 18 October 2000 Personal Interview No. 8: Oonagh Marron (A) 17 October 2000 Personal Interview No. 9: Oonagh Marron (B) 23 October 2000 Personal Interview No. 10: Helena Schlindwein 28 October 2000 Personal Interview No. 11 30 October 2000 Personal Interview No. 12 1 November 2000 Personal Interview No. 13 1 November 2000 Personal Interview No. 14: Claire Hackett 7 November 2000 Personal Interview No. 15: Meta Auden 15 November 2000 Personal Interview No. 16 1 June 2000 Personal Interview Maggie Feeley 30 August 2005 Personal Interview No. 18 4 August 2009 Personal Interview No. 19: Marie Mulholland 27 August 2009 Personal Interview No. 20 3 February 2010 Personal Interview No. 21A (joint interview) 23 February 2010 Personal Interview No. 21B (joint interview) 23 February 2010 * Locations are omitted from this list so as to preserve the identity of the respondents. 203 Notes 1 Introduction: Rethinking Women and Nationalism 1 . I will return to this argument in a subsequent section dedicated to women’s victimisation as ‘women as reproducers’ of the nation. See also, Beverly Allen, Rape Warfare: The Hidden Genocide in Bosnia-Herzegovina (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 1996); Alexandra Stiglmayer, (ed.), Mass Rape: The War Against Women in Bosnia- Herzegovina (Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 1994); Carolyn Nordstrom, Fieldwork Under Fire: Contemporary Studies of Violence and Survival (Berkeley: University of California, 1995); Jill Benderly, ‘Rape, feminism, and nationalism in the war in Yugoslav successor states’ in Lois West, ed., Feminist Nationalism (London and New Tork: Routledge, 1997); Cynthia Enloe, ‘When soldiers rape’ in Maneuvers: The International Politics of Militarizing Women’s Lives (Berkeley: University of California, 2000). -

Irish Political Studies the Art and Effect of Political Lying in Northern Ireland

This article was downloaded by: [The Library at Queen's University] On: 06 May 2015, At: 09:02 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Irish Political Studies Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fips20 The Art and Effect of Political Lying in Northern Ireland Arthur Aughey Published online: 08 Sep 2010. To cite this article: Arthur Aughey (2002) The Art and Effect of Political Lying in Northern Ireland, Irish Political Studies, 17:2, 1-16, DOI: 10.1080/714003199 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/714003199 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. -

Critical Engagement: Irish Republicanism, Memory Politics

Critical Engagement Critical Engagement Irish republicanism, memory politics and policing Kevin Hearty LIVERPOOL UNIVERSITY PRESS First published 2017 by Liverpool University Press 4 Cambridge Street Liverpool L69 7ZU Copyright © 2017 Kevin Hearty The right of Kevin Hearty to be identified as the author of this book has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication data A British Library CIP record is available print ISBN 978-1-78694-047-6 epdf ISBN 978-1-78694-828-1 Typeset by Carnegie Book Production, Lancaster Contents Acknowledgements vii List of Figures and Tables x List of Abbreviations xi Introduction 1 1 Understanding a Fraught Historical Relationship 25 2 Irish Republican Memory as Counter-Memory 55 3 Ideology and Policing 87 4 The Patriot Dead 121 5 Transition, ‘Never Again’ and ‘Moving On’ 149 6 The PSNI and ‘Community Policing’ 183 7 The PSNI and ‘Political Policing’ 217 Conclusion 249 References 263 Index 303 Acknowledgements Acknowledgements This book has evolved from my PhD thesis that was undertaken at the Transitional Justice Institute, University of Ulster (TJI). When I moved to the University of Warwick in early 2015 as a post-doc, my plans to develop the book came with me too. It represents the culmination of approximately five years of research, reading and (re)writing, during which I often found the mere thought of re-reading some of my work again nauseating; yet, with the encour- agement of many others, I persevered. -

Bridie O'byrne

INTERVIEWS We moved then from Castletown Cross to Dundalk. My father was on the Fire Brigade in Dundalk and we had to move into town and we Bridie went to the firemen’s houses in Market Street. Jack, my eldest brother, was in the army at the time and as my father grew older Jack O’Byrne eventually left the army. He got my father’s job in the Council driving on the fire brigade and nee Rooney, steamroller and things. boRn Roscommon, 1919 Then unfortunately in 1975 a bomb exploded in ’m Bridie O’Byrne - nee Crowes Street (Dundalk). I was working in the Echo at the time and I was outside the Jockeys Rooney. I was born in (pub) in Anne Street where 14 of us were going Glenmore, Castletown, out for a Christmas drink. It was about five minutes to six and the bomb went off. At that in Roscommon 90 time I didn’t know my brother was involved in years ago 1 . My it. We went home and everyone was talking Imother was Mary Harkin about the bomb and the bomb. The following day myself and my youngest son went into town from Roscommon and my to get our shopping. We went into Kiernan’s first father was Patrick Rooney to order the turkey and a man there asked me from Glenmore. I had two how my brother was and, Lord have mercy on Jack, he had been sick so I said, “Oh he’s grand. “Did you brothers Jack and Tom and He’s back to working again.” And then I got to not know my sister Molly; just four of White’s in Park Street and a woman there asked me about my brother and I said to her, “Which that your us in the family. -

Irish Film and Television - 2018

Estudios Irlandeses, Issue 14, March 2019-Feb. 2020, pp. 294-327 __________________________________________________________________________________________ AEDEI IRISH FILM AND TELEVISION - 2018 THE YEAR IN REVIEW Roddy Flynn, Tony Tracy (eds.) Copyright (c) 2019 by the authors. This text may be archived and redistributed both in electronic form and in hard copy, provided that the author and journal are properly cited and no fee is charged for access. Introduction. Fin de Cinema? The Irish Screen Sector in 2018. Roddy Flynn, Tony Tracy……………...………………………………………………..…..295 Documentary as Diversion: A Mother Brings Her Son to be Shot (Sinéad O’Shea, 2017) Eileen Culloty……………….………..……………….………………………………….…305 In the Name of Peace: John Hume in America (Maurice Fitzpatrick, 2018) Seán Crosson………….…………….………………….………………………….………...308 Déjà Vu? The Audiovisual Action Plan (2018) Roddy Flynn…………………….…………..…………………………..…………………...310 The Lonely Battle of Thomas Reid (Fergal Ward, 2018) Roddy Flynn ………………………………………………………………………………...317 Fear, Loathing (and Industrial Relations) in the Irish film Industry Denis Murphy……………………………………..…………………………..…………….321 Searching for Understanding in Alan Gilsenan’s The Meeting Aileen O’Driscoll……………………………………………………………………………324 ISSN 1699-311X 295 Introduction. Fin de Cinema? The Irish Screen Sector in 2018. Tony Tracy, Roddy Flynn In July 2018, the Irish Film Board announced that it was changing its name to Screen Ireland. It was done with relatively little fanfare or media attention and indeed still has to fully work through: as late as January 2019 Irish films were being simultaneously released into cinemas bearing alternately the Irish Film Board or Screen Ireland logos. Was this the year in review’s defining event or simply a timely re-branding? Either way, what might the change tell us? In announcing the change, a PR release explained that the new name reflects the agency’s “redefined, broadened remit, which has been driven both by the changing and diverse nature of the industry and audience content consumption.