ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Father of the House Sarah Priddy

BRIEFING PAPER Number 06399, 17 December 2019 By Richard Kelly Father of the House Sarah Priddy Inside: 1. Seniority of Members 2. History www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary Number 06399, 17 December 2019 2 Contents Summary 3 1. Seniority of Members 4 1.1 Determining seniority 4 Examples 4 1.2 Duties of the Father of the House 5 1.3 Baby of the House 5 2. History 6 2.1 Origin of the term 6 2.2 Early usage 6 2.3 Fathers of the House 7 2.4 Previous qualifications 7 2.5 Possible elections for Father of the House 8 Appendix: Fathers of the House, since 1901 9 3 Father of the House Summary The Father of the House is a title that is by tradition bestowed on the senior Member of the House, which is nowadays held to be the Member who has the longest unbroken service in the Commons. The Father of the House in the current (2019) Parliament is Sir Peter Bottomley, who was first elected to the House in a by-election in 1975. Under Standing Order No 1, as long as the Father of the House is not a Minister, he takes the Chair when the House elects a Speaker. He has no other formal duties. There is evidence of the title having been used in the 18th century. However, the origin of the term is not clear and it is likely that different qualifications were used in the past. The Father of the House is not necessarily the oldest Member. -

Black Women, Educational Philosophies, and Community Service, 1865-1965/ Stephanie Y

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-2003 Living legacies : Black women, educational philosophies, and community service, 1865-1965/ Stephanie Y. Evans University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Evans, Stephanie Y., "Living legacies : Black women, educational philosophies, and community service, 1865-1965/" (2003). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 915. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/915 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. M UMASS. DATE DUE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS AMHERST LIVING LEGACIES: BLACK WOMEN, EDUCATIONAL PHILOSOPHIES, AND COMMUNITY SERVICE, 1865-1965 A Dissertation Presented by STEPHANIE YVETTE EVANS Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2003 Afro-American Studies © Copyright by Stephanie Yvette Evans 2003 All Rights Reserved BLACK WOMEN, EDUCATIONAL PHILOSOHIES, AND COMMUNITY SERVICE, 1865-1964 A Dissertation Presented by STEPHANIE YVETTE EVANS Approved as to style and content by: Jo Bracey Jr., Chair William Strickland, -

Subversive Legal Moments? Elizabeth M

Brooklyn Law School BrooklynWorks Faculty Scholarship Spring 2003 Roundtable: Subversive Legal Moments? Elizabeth M. Schneider Brooklyn Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/faculty Recommended Citation 12 Tex. J. Women & L. 197 (2002-2003) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of BrooklynWorks. Texas Journal of Women and the Law Volume 12 ROUND TABLE DISCUSSION: SUBVERSIVE LEGAL MOMENTS? Karen Engle*: Good morning, and welcome to the first roundtable, which is in many ways a Rorschach test. In your packet, you have a handout that says Frontiero v. Richardson on the front. You might want to take it out and have it in front of you during the panel because we are going to focus on the cases included in the packet. We are delighted to have such a multidisciplinary audience here and hope the handout will assist those who might not be particularly familiar with the cases or who, in any event, could use a refresher. We have before us five eminent legal scholars. I will introduce them in the order they will be speaking this morning: Elizabeth Schneider, Vicki Schultz, Nathaniel Berman, Adrienne Davis, and Janet Halley. All of them have focused on or used theories about gender in their work, some to a greater extent than others, but all quite thoughtfully. We also have five famous legal cases. Most are cases that were brought by women's rights advocates in a deliberate attempt to move the law in a direction that would better attend to women's concerns. -

Identity, Authority and Myth-Making: Politically-Motivated Prisoners and the Use of Music During the Northern Irish Conflict, 1962 - 2000

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Queen Mary Research Online Identity, authority and myth-making: Politically-motivated prisoners and the use of music during the Northern Irish conflict, 1962 - 2000 Claire Alexandra Green Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 1 I, Claire Alexandra Green, confirm that the research included within this thesis is my own work or that where it has been carried out in collaboration with, or supported by others, that this is duly acknowledged below and my contribution indicated. Previously published material is also acknowledged below. I attest that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge break any UK law, infringe any third party’s copyright or other Intellectual Property Right, or contain any confidential material. I accept that the College has the right to use plagiarism detection software to check the electronic version of the thesis. I confirm that this thesis has not been previously submitted for the award of a degree by this or any other university. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. Signature: Date: 29/04/19 Details of collaboration and publications: ‘It’s All Over: Romantic Relationships, Endurance and Loyalty in the Songs of Northern Irish Politically-Motivated Prisoners’, Estudios Irlandeses, 14, 70-82. 2 Abstract. In this study I examine the use of music by and in relation to politically-motivated prisoners in Northern Ireland, from the mid-1960s until 2000. -

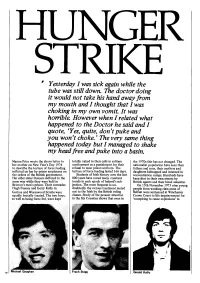

Article on Hungerstrike

" Yesterday I was sick again while the tube was still down. The doctor doing it would not take his hand away [rom my mouth and I thought that I was choking in my own vomit. It was homble. However when I related what happened to the Doctor he said and I quote, 'Yes, quite, don'tpuke and you won't choke. ' The very same thing happened today but I managed to shake my head [ree and puke into a basin. Marian Price wrote the above letter to totaHy naked in their ceHs in solitary the 1970s this has not changed. The her mother on New Year's Day 1974 confinement as a punishment for their nationalist population have seen their to describe the torture of force feeding refusal to wear prison uniform. The fathers and sons, their mothers and inflicted on her by prison employees on torture of force feeding lasted 166 days. daughters kidnapped and interned in the orders of the British government. Students of Irish history over the last concentration camps. Hundreds have Her eIder sister Dolours suffered in the 800 years have noted many constant been shot in their own streets by same way while they were held in trends in each epoch of Ireland's sub• British agents and their hired assassins. Brixton's men's prison. Their comrades jection. The most frequent is un• On 15th November 1973 nine young Hugh Feeney and Gerry KeHy in doubtedly the vicious treatment meted people from working class areas of Gartree and Wormwood Scrubs were out to the Irish by the British ruling Belfast were sentenced at Winchester equally brutally treated. -

Black Anarchism, Pedro Riberio

TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction.....................................................................................................................2 2. The Principles of Anarchism, Lucy Parsons....................................................................3 3. Anarchism and the Black Revolution, Lorenzo Komboa’Ervin......................................10 4. Beyond Nationalism, But not Without it, Ashanti Alston...............................................72 5. Anarchy Can’t Fight Alone, Kuwasi Balagoon...............................................................76 6. Anarchism’s Future in Africa, Sam Mbah......................................................................80 7. Domingo Passos: The Brazilian Bakunin.......................................................................86 8. Where Do We Go From Here, Michael Kimble..............................................................89 9. Senzala or Quilombo: Reflections on APOC and the fate of Black Anarchism, Pedro Riberio...........................................................................................................................91 10. Interview: Afro-Colombian Anarchist David López Rodríguez, Lisa Manzanilla & Bran- don King........................................................................................................................96 11. 1996: Ballot or the Bullet: The Strengths and Weaknesses of the Electoral Process in the U.S. and its relation to Black political power today, Greg Jackson......................100 12. The Incomprehensible -

Working Against Racism from White Subject Positions: White Anti-Racism, New Abolitionism & Intersectional Anti-White Irish Diasporic Nationalism

Working Against Racism from White Subject Positions: White Anti-Racism, New Abolitionism & Intersectional Anti-White Irish Diasporic Nationalism By Matthew W. Horton A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Education and the Designated Emphasis in Critical Theory in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Dr. Na’ilah Nasir, Chair Dr. Daniel Perlstein Dr. Keith Feldman Summer 2019 Working Against Racism from White Subject Positions Matthew W. Horton 2019 ABSTRACT Working Against Racism from White Subject Positions: White Anti-Racism, New Abolitionism & Intersectional Anti-White Irish Diasporic Nationalism by Matthew W. Horton Doctor of Philosophy in Education and the Designated Emphasis in Critical Theory University of California, Berkeley Professor Na’ilah Nasir, Chair This dissertation is an intervention into Critical Whiteness Studies, an ‘additional movement’ to Ethnic Studies and Critical Race Theory. It systematically analyzes key contradictions in working against racism from a white subject positions under post-Civil Rights Movement liberal color-blind white hegemony and "Black Power" counter-hegemony through a critical assessment of two major competing projects in theory and practice: white anti-racism [Part 1] and New Abolitionism [Part 2]. I argue that while white anti-racism is eminently practical, its efforts to hegemonically rearticulate white are overly optimistic, tend toward renaturalizing whiteness, and are problematically dependent on collaboration with people of color. I further argue that while New Abolitionism has popularized and advanced an alternative approach to whiteness which understands whiteness as ‘nothing but oppressive and false’ and seeks to ‘abolish the white race’, its ultimately class-centered conceptualization of race and idealization of militant nonconformity has failed to realize effective practice. -

Thatcher, Northern Ireland and Anglo-Irish Relations, 1979-1990

From ‘as British as Finchley’ to ‘no selfish strategic interest’: Thatcher, Northern Ireland and Anglo-Irish Relations, 1979-1990 Fiona Diane McKelvey, BA (Hons), MRes Faculty of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences of Ulster University A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Ulster University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2018 I confirm that the word count of this thesis is less than 100,000 words excluding the title page, contents, acknowledgements, summary or abstract, abbreviations, footnotes, diagrams, maps, illustrations, tables, appendices, and references or bibliography Contents Acknowledgements i Abstract ii Abbreviations iii List of Tables v Introduction An Unrequited Love Affair? Unionism and Conservatism, 1885-1979 1 Research Questions, Contribution to Knowledge, Research Methods, Methodology and Structure of Thesis 1 Playing the Orange Card: Westminster and the Home Rule Crises, 1885-1921 10 The Realm of ‘old unhappy far-off things and battles long ago’: Ulster Unionists at Westminster after 1921 18 ‘For God's sake bring me a large Scotch. What a bloody awful country’: 1950-1974 22 Thatcher on the Road to Number Ten, 1975-1979 26 Conclusion 28 Chapter 1 Jack Lynch, Charles J. Haughey and Margaret Thatcher, 1979-1981 31 'Rise and Follow Charlie': Haughey's Journey from the Backbenches to the Taoiseach's Office 34 The Atkins Talks 40 Haughey’s Search for the ‘glittering prize’ 45 The Haughey-Thatcher Meetings 49 Conclusion 65 Chapter 2 Crisis in Ireland: The Hunger Strikes, 1980-1981 -

Free Derry – a “No Go” Area

MODULE 1. THE NORTHERN IRELAND CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT 5: FREE DERRY – A “NO GO” AREA LESSON LESSON DESCRIPTION 5. This lesson will follow up on the events of The Battle of the Bogside and look at the establishment of a “No Go” area in the Bogside of Derry/Londonderry. The lesson will examine the reasons why it was set up and how it was maintained and finally how it came to an end. LESSON INTENTIONS LESSON OUTCOMES 1. Explain the reasons why • Students will be able to explain barricades remained up after the the reasons why “Free Derry” was Battle of the Bogside. able to exist after the Battle of the 2. Explain the reasons why the Bogside had ended and how it barricades were taken down. came to an end. 3. Demonstrate objectives 1 & 2 • Employ ICT skills to express an through digital media. understanding of the topic HANDOUTS DIGITAL SOFTWARE HARDWARE AND GUIDES • Lesson 5 Key • Suggested • Image • Whiteboard Information Additional Editing • PCs / Laptops Resources Software • M1L5 • Headphones / e.g. GIMP Statements Microphone • Digital • Audio Imaging Editing Design Sheet Software e.g. • Audio Editing Audacity Storyboard www.nervecentre.org/teachingdividedhistories MODULE 1: LESSON 5: LESSON PLAN 61 MODULE 1. THE NORTHERN IRELAND CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT 5: FREE DERRY – A “NO GO” AREA ACTIVITY LEARNING OUTCOMES Show the class a news report via This will give the pupils an insight as BBC archive footage which reports to how and why the barricades were on the events of the Battle of the erected around the Bogside area of Bogside (see Suggested Additional Derry/Londonderry. -

The Path to Revolutionary Violence Within the Weather Underground and Provisional IRA

The Path to Revolutionary Violence within the Weather Underground and Provisional IRA Edward Moran HIS 492: Seminar in History December 17, 2019 Moran 1 The 1960’s was a decade defined by a spirit of activism and advocacy for change among oppressed populations worldwide. While the methods for enacting change varied across nations and peoples, early movements such as that for civil rights in America were often committed to peaceful modes of protest and passive resistance. However, the closing years of the decade and the dawn of the 1970’s saw the patterned global spread of increasingly militant tactics used in situations of political and social unrest. The Weather Underground Organization (WUO) in America and the Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA) in Ireland, two such paramilitaries, comprised young activists previously involved in the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and the Northern Irish Civil Rights Association (NICRA) respectively. What caused them to renounce the non-violent methods of the Students for a Democratic Society and the Northern Irish Civil Rights Association for the militant tactics of the Weather Underground and Irish Republican Army, respectively? An analysis of contemporary source materials, along with more recent scholarly works, reveals that violent state reactions to more passive forms of demonstration in the United States and Northern Ireland drove peaceful activists toward militancy. In the case of both the Weather Underground and the Provisional Irish Republican Army in the closing years of the 1960s and early years of the 1970s, the bulk of combatants were young people with previous experience in more peaceful campaigns for civil rights and social justice. -

Extremism and Terrorism

Ireland: Extremism and Terrorism On December 19, 2019, Cloverhill District Court in Dublin granted Lisa Smith bail following an appeal hearing. Smith, a former member of the Irish Defense Forces, was arrested at Dublin Airport on suspicion of terrorism offenses following her return from Turkey in November 2019. According to Irish authorities, Smith was allegedly a member of ISIS. Smith was later examined by Professor Anne Speckhard who determined that Smith had “no interest in rejoining or returning to the Islamic State.” Smith’s trial is scheduled for January 2022. (Sources: Belfast Telegraph, Irish Post) Ireland saw an increase in Islamist and far-right extremism throughout 2019, according to Europol. In 2019, Irish authorities arrested five people on suspicions of supporting “jihadi terrorism.” This included Smith’s November 2019 arrest. An additional four people were arrested for financing jihadist terrorism. Europol also noted a rise in far-right extremism, based on the number of Irish users in leaked user data from the far-right website Iron March. (Source: Irish Times) Beginning in late 2019, concerns grew that the possible return of a hard border between British-ruled Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland after Brexit could increase security tensions in the once war-torn province. The Police Services of Northern Ireland recorded an increase in violent attacks along the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland border in 2019 and called on politicians to take action to heal enduring divisions in society. According to a representative for the New IRA—Northern Ireland’s largest dissident organization—the uncertainty surrounding Brexit provided the group a politicized platform to carry out attacks along the U.K. -

Mr Andrew Mackay and Ms Julie Kirkbride

House of Commons Committee on Standards and Privileges Mr Andrew Mackay and Ms Julie Kirkbride Fifth Report of Session 2010–11 Report and Appendices, together with formal minutes Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 19 October2010 HC 540 Published on 21 October 2010 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £0.00 The Committee on Standards and Privileges The Committee on Standards and Privileges is appointed by the House of Commons to oversee the work of the Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards; to examine the arrangements proposed by the Commissioner for the compilation, maintenance and accessibility of the Register of Members’ Interests and any other registers of interest established by the House; to review from time to time the form and content of those registers; to consider any specific complaints made in relation to the registering or declaring of interests referred to it by the Commissioner; to consider any matter relating to the conduct of Members, including specific complaints in relation to alleged breaches in the Code of Conduct which have been drawn to the Committee’s attention by the Commissioner; and to recommend any modifications to the Code of Conduct as may from time to time appear to be necessary. Current membership Rt hon Kevin Barron MP (Labour, Rother Valley) (Chair) Sir Paul Beresford MP (Conservative, Mole Valley) Annette Brooke MP (Liberal Democrat, Mid Dorset and North Poole) Rt hon Tom Clarke MP (Labour, Coatbridge, Chryston and Bellshill) Mr Geoffrey Cox MP (Conservative, Torridge and West Devon) Mr Jim Cunningham MP (Labour, Coventry South) Mr Oliver Heald MP (Conservative, North East Hertfordshire) Eric Ollerenshaw MP (Conservative, Lancaster and Fleetwood) Heather Wheeler MP (Conservative, South Derbyshire) Dr Alan Whitehead MP (Labour, Southampton Test) Powers The constitution and powers of the Committee are set out in Standing Order No.