The New Jersey National Guard, 1869 to 1900 in April 1869, New Jersey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Modern Application of Mechanized-Cavalry Groups for Cavalry Echelons Above Brigade by MAJ Joseph J

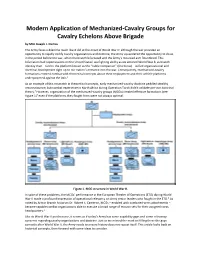

Modern Application of Mechanized-Cavalry Groups for Cavalry Echelons Above Brigade by MAJ Joseph J. Dumas The Army faces a dilemma much like it did at the onset of World War II: although the war provided an opportunity to rapidly codify cavalry organizations and doctrine, the Army squandered the opportunity to do so in the period before the war, when the branch bifurcated and the Army’s mounted arm floundered. This bifurcation had repercussions on the United States’ warfighting ability as we entered World War II, as branch identity then – tied to the platform known as the “noble companion” (the horse) – stifled organizational and doctrinal development right up to our nation’s entrance into the war. Consequently, mechanized-cavalry formations entered combat with theoretical concepts about their employment and their vehicle platforms underpowered against the Axis.1 As an example of this mismatch in theoretical concepts, early mechanized-cavalry doctrine peddled stealthy reconnaissance, but combat experience in North Africa during Operation Torch didn’t validate pre-war doctrinal theory.2 However, organization of the mechanized-cavalry groups (MCGs) created effective formations (see Figure 1)3 even if the platforms they fought from were not always optimal. Figure 1. MCG structure in World War II. In spite of these problems, the MCGs’ performance in the European Theater of Operations (ETO) during World War II made a profound impression of operational relevancy on Army senior leaders who fought in the ETO.4 As noted by Armor Branch historian Dr. Robert S. Cameron, MCGs – enabled with combined-arms attachments – became capable combat organizations able to execute a broad range of mission sets for their assigned corps headquarters.5 Like its World War II predecessor, it seems as if today’s Army has some capability gaps and some relevancy concerns regarding cavalry organizations and doctrine. -

The African American Soldier at Fort Huachuca, Arizona, 1892-1946

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Faculty Publications Anthropology, Department of 2-2001 The African American Soldier At Fort Huachuca, Arizona, 1892-1946 Steven D. Smith University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/anth_facpub Part of the Anthropology Commons Publication Info Published in 2001. © 2001, University of South Carolina--South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology This Book is brought to you by the Anthropology, Department of at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE AFRICAN AMERICAN SOLDIER AT FORT HUACHUCA, ARIZONA, 1892-1946 The U.S Army Fort Huachuca, Arizona, And the Center of Expertise for Preservation of Structures and Buildings U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Seattle District Seattle, Washington THE AFRICAN AMERICAN SOLDIER AT FORT HUACHUCA, ARIZONA, 1892-1946 By Steven D. Smith South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology University of South Carolina Prepared For: U.S. Army Fort Huachuca, Arizona And the The Center of Expertise for Preservation of Historic Structures & Buildings, U.S. Army Corps of Engineer, Seattle District Under Contract No. DACW67-00-P-4028 February 2001 ABSTRACT This study examines the history of African American soldiers at Fort Huachuca, Arizona from 1892 until 1946. It was during this period that U.S. Army policy required that African Americans serve in separate military units from white soldiers. All four of the United States Congressionally mandated all-black units were stationed at Fort Huachuca during this period, beginning with the 24th Infantry and following in chronological order; the 9th Cavalry, the 10th Cavalry, and the 25th Infantry. -

Congressional Record- House. May 23

5868 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD- HOUSE. MAY 23, Homer B. Grant, of Massachusetts, late first lieutenant, Twenty Irwin G. Lukens, to be postmaster at North Wales, in the county sixth Infantry, United States Volunteers (now second lieutenant, of Montgomery and State of Pe..~ylvania. Artillery Corps, United States Army), to fill an original vacancy. Benjamin Jacobs, to be postmaster at Pencoyd, in the county John W. C. Abbott, at large, late first lieutenant, Thirtieth In of Montgomery and State of Pennsylvania. fantry, United States Volunteers (now second lieutenant, Artillery JohnS. Buchanan, to be postmaster at Ambler, in the county Corps, United States Army), to fill an original vacancy. of Montgomery and State of Pennsylvania. John McBride, jr., at large, late first lieutenant, Thirtieth In Henry C. Connaway, to be postmaster at Berlin, in the county fantry, United States Volunteers (now second lieutenant, Artillery of Worcester and State of Mal'yland. Corps, United States Army), to fill an original vacancy. Harrison S. Kerrick, of Illinois, late captain, Thirtieth Infan try, United States Volunteers (now second lieutenant, Artillery HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES. Corps, United States Army), to fill an original vacancy. Frank J. Miller, at large, late first lieutenant, Forty-first Infan FRIDAY, May 23, 1902. try, United States Volunteers (now second lieutenant, Artillery The House met at 12 o'clock m. Prayer by the Chaplain, Rev. Corps, United States Army), to fill an original vacancy. HENRY N. COUDEN, D. D. Charles L. Lanham, at large, late first lieutenant, Forty-seventh The Journal of the proceedings of yestel'day was read and ap Infantry, United States Volunteers (now second lieutenant, Artil proved. -

Garrison Life of the Mounted Soldier on the Great Plains

/7c GARRISON LIFE OF THE MOUNTED SOLDIER ON THE GREAT PLAINS, TEXAS, AND NEW MEXICO FRONTIERS, 1833-1861 THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Stanley S. Graham, B. A. Denton, Texas August, 1969 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page MAPS ..................... .... iv Chapter I. THE REGIMENTS AND THE POSTS . .. 1 II. RECRUITMENT........... ........ 18 III. ROUTINE AT THE WESTERN POSTS ..0. 40 IV. RATIONS, CLOTHING, PROMOTIONS, PAY, AND CARE OF THE DISABLED...... .0.0.0.* 61 V. DISCIPLINE AND RELATED PROBLEMS .. 0 86 VI. ENTERTAINMENT, MORAL GUIDANCE, AND BURIAL OF THE FRONTIER..... 0. 0 . 0 .0 . 0. 109 VII. CONCLUSION.............. ...... 123 BIBLIOGRAPHY.......... .............. ....... ........ 126 iii LIST OF MAPS Figure Page 1. Forts West of the Mississippi in 1830 . .. ........ 15 2. Great Plains Troop Locations, 1837....... ............ 19 3. Great Plains, Texas, and New Mexico Troop Locations, 1848-1860............. ............. 20 4. Water Route to the West .......................... 37 iv CHAPTER I THE REGIMENTS AND THE POSTS The American cavalry, with a rich heritage of peacekeeping and combat action, depending upon the particular need in time, served the nation well as the most mobile armed force until the innovation of air power. In over a century of performance, the army branch adjusted to changing times and new technological advances from single-shot to multiple-shot hand weapons for a person on horseback, to rapid-fire rifles, and eventually to an even more mobile horseless, motor-mounted force. After that change, some Americans still longed for at least one regiment to be remounted on horses, as General John Knowles Herr, the last chief of cavalry in the United States Army, appealed in 1953. -

70Th Annual 1St Cavalry Division Association Reunion

1st Cavalry Division Association 302 N. Main St. Non-Profit Organization Copperas Cove, Texas 76522-1703 US. Postage PAID West, TX Change Service Requested 76691 Permit No. 39 PublishedSABER By and For the Veterans of the Famous 1st Cavalry Division VOLUME 66 NUMBER 1 Website: http://www.1cda.org JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2017 The President’s Corner Horse Detachment by CPT Jeremy A. Woodard Scott B. Smith This will be my last Horse Detachment to Represent First Team in Inauguration Parade By Sgt. 833 State Highway11 President’s Corner. It is with Carolyn Hart, 1st Cav. Div. Public Affairs, Fort Hood, Texas. Laramie, WY 82070-9721 deep humility and considerable A long standing tradition is being (307) 742-3504 upheld as the 1st Cavalry Division <[email protected]> sorrow that I must announce my resignation as the President Horse Cavalry Detachment gears up to participate in the Inauguration of the 1st Cavalry Division Association effective Saturday, 25 February 2017. Day parade Jan. 20 in Washington, I must say, first of all, that I have enjoyed my association with all of you over D.C. This will be the detachment’s the years…at Reunions, at Chapter meetings, at coffees, at casual b.s. sessions, fifth time participating in the event. and at various activities. My assignments to the 1st Cavalry Division itself and “It’s a tremendous honor to be able my friendships with you have been some of the highpoints of my life. to do this,” Capt. Jeremy Woodard, To my regret, my medical/physical condition precludes me from travelling. -

1892-1918 by Bachelor of Arts Chapman University

THE FIGHTINGlENTH CAVALRY: BLACK SOLDIERS IN THE UNITED STATES ARMY 1892-1918 By DAVID K. WORK Bachelor of Arts Chapman University Orange, California 199,5 Bachelor of Fine Arts Chapman University Orange, California 1995 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May, 1998 THE FIGHTING TENTH CAVALRY: BLACK SOLDIERS IN THE UNITED STATES ARMY 1892-1918 Thesis Approved: 11 PREFACE On August 4, 1891, Colonel 1. K. Mizner, the commanding officer of the Tenth United States Cavalry Regiment, asked the Adjutant General of the army to transfer the Tenth Cavalry from Arizona "to a northern climate." For over twenty years, the Colonel complained, the Tenth had served in the Southwest, performing the most difficult field service of any regiment in the army and living in the worst forts in the country. No other cavalry regiment had "been subject to so great an amount of hard, fatigueing and continueing [sic]" service as the Tenth, service that entitled it "to as good stations as can be assigned. II Mizner challenged the Adjutant General to make his decision based on "just consideration" and not to discriminate against the Tenth "on account of the color of the enlisted men." t As one of fOUf regiments in the post-Civil War Army composed entirely of black enlisted men, discrimination was a problem the Tenth Cavalry constantly faced. Whether it was poor horses and equipment, inferior posts and assignments, or the hostility of the white communities the regiment protected, racial prejudice was an inescapable part of the regiment's daily life. -

Washington National Guard Pamphlet

WASH ARNG PAM 870-1-5 WASH ANG PAM 210-1-5 WASHINGTON NATIONAL GUARD PAMPHLET THE OFFICIAL HISTORY OF THE WASHINGTON NATIONAL GUARD VOLUME 5 WASHINGTON NATIONAL GUARD IN WORLD WAR I HEADQUARTERS MILITARY DEPARTMENT STATE OF WASHINGTON OFFICE OF THE ADJUTANT GENERAL CAMP MURRAY, TACOMA 33, WASHINGTON THIS VOLUME IS A TRUE COPY THE ORIGINAL DOCUMENT ROSTERS HEREIN HAVE BEEN REVISED BUT ONLY TO PUT EACH UNIT, IF POSSIBLE, WHOLLY ON A SINGLE PAGE AND TO ALPHABETIZE THE PERSONNEL THEREIN DIGITIZED VERSION CREATED BY WASHINGTON NATIONAL GUARD STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY VOLUME 5 WASHINGTON NATIONAL GUARD IN WORLD WAR I. CHAPTER PAGE I WASHINGTON NATIONAL GUARD IN THE POST ..................................... 1 PHILIPPINE INSURRECTION PERIOD II WASHINGTON NATIONAL GUARD MANEUVERS ................................. 21 WITH REGULAR ARMY 1904-12 III BEGINNING OF THE COAST ARTILLERY IN ........................................... 34 THE WASHINGTON NATIONAL GUARD IV THE NAVAL MILITIA OF THE WASHINGTON .......................................... 61 NATIONAL GUARD V WASHINGTON NATIONAL GUARD IN THE ............................................. 79 MEXICAN BORDER INCIDENT VI WASHINGTON NATIONAL GUARD IN THE ........................................... 104 PRE - WORLD WAR I PERIOD VII WASHINGTON NATIONAL GUARD IN WORLD WAR I .......................114 - i - - ii - CHAPTER I WASHINGTON NATIONAL GUARD IN THE POST PHILIPPINE INSURRECTION PERIOD It may be recalled from the previous chapter that with the discharge of members of the Washington National Guard to join the First Regiment of United States Volunteers and the federalizing of the Independent Washington Battalion, the State was left with no organized forces. Accordingly, Governor Rogers, on 22 July 1898, directed Adjutant General William J. Canton to re-establish a State force in Conformity with the Military Code of Washington. -

Congressional Record-House House Of

1935 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-HOUSE 2029 MISSISSIPPI dom in all our deliberations of this day. May we ever lean Malcolm E. Wilson, Marks. on Thy strong arm and keep so close to Thee that we shall Henry W. Mangum, Mendenhall. feel the pulsations of Thy great heart of love. Bless our Singleton C. Tanner, Mize. President, our beloved Speaker of this House of Representa Olive Alexander, Rolling Fork. tives, and every Member thereof, and may our one great desire be to render Thee such service, in both national and MISSOURI private life, that when the great day of reckoning comes we Giles K. Hunt, Arcadia: may hear Thy Son say, "Come ye blessed of my Father, Ezra W. Mott, Armstrong. inherit the kingdom prepared for you from the foundation Samuel S. Harrison, Auxvasse. of the world." In Jesus' name we a.skit. Amen. Reece G. Allen, Benton. Herman C. W. Strothmann, Berger. The Journal of the proceedings of yesterday was read and John H. Essman, Bourbon. approved. Fred R. Morrow, Bufialo. ADJOURNMENT OVER Angie B. Messbarger, Burlington Junction. Mr. TAYLOR of Colorado. Mr. Speaker, I ask unanimous Frank F. Page, Canton. consent that when the House adjourns today it adjourn to George K. Spalding, Chesterfield. meet on Monday next at noon. Melville C. Shores, Clark. The SPEAKER. Is there objection to the request of the Allen W. Sapp, Columbia. gentleman from Colorado? · Harold H. Cash, Curryville. There was no objection. George W. Shelton, Dixon. INTERSTATE AND FOREIGN COMMERCE IN PETROLEUM Charles Shumate, Edina. Mr. DIES, from the Committee on Rules, submitted the Vernon D. -

Militiamen and Frontiers: Changes in the Militia from the Peace of Paris to the Great War

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1995 Militiamen and frontiers: Changes in the militia from the Peace of Paris to the Great War Barry M. Stentiford The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Stentiford, Barry M., "Militiamen and frontiers: Changes in the militia from the Peace of Paris to the Great War" (1995). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 8838. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/8838 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I L Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY The University ofIVIONTANA Permission is granted by the author to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that this material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. ** Please check ”Yes" or '"No" and provide signature** Yes, I grant permission N o, I do not grant permission Author's Signature /V l., Date II ______ Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author's explicit consent. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. -

Fort Davis U.S

National Historic Site National Park Service Fort Davis U.S. Department of the Interior JULY 1866: A MILESTONE IN BLACK HISTORY THE ESTABLISHMENT OF BLACK REGIMENTS IN THE REGULAR ARMY It was opposed by many, considered only an experiment by others, but the “Act to Increase THE NINTH AND and Fix the Military Peace Establishment of the TENTH CAVALRY United States” changed the course of American Military History, and afforded blacks a permanent The Ninth Cavalry initially saw action in Texas place in the Armed Forces of the United States. with Companies C, F, H, and I reoccupying the abandoned post at Fort Davis on June 29, 1867. The Act of Congress, dated July 28, 1866, The first home of the Tenth Cavalry was Fort increased the size of the regular peacetime army Leavenworth, Kansas. After seeing duty in by raising the number of infantry regiments from Kansas, Oklahoma and Colorado, the regiment nineteen to forty- five. The legislation stipulated came to Texas in 1875. It was troopers of these that of the new regiments created, two cavalry and two cavalry regiments that earned the nickname four infantry “shall be composed of colored men.” “Buffalo Soldiers” – a term given them by the For the first time in the history of the United Indians because of the resemblance of their hair States, regiments composed of black troops were to the short, curly hair of the buffalo. authorized as part of the Regular Army. THE INFANTRY As slaves and as free men, blacks participated in REGIMENTS the French and Indian Wars. They fought under Generals Braddock and Washington in the In 1869, the infantry regiments underwent American Revolutionary War. -

Sabers and Saddles: the Second Regiment of United

SABERS AND SADDLES: THE SECOND REGIMENT OF UNITED STATES DRAGOONS AT FORT WASHITA, 1842-1845 By DAVID C. REED Bachelor of Arts in History/Communications Southeastern Oklahoma State University Durant, Oklahoma 2008 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS May, 2013 SABERS AND SADDLES: THE SECOND REGIMENT OF UNITED STATES DRAGOONS AT FORT WASHITA, 1842-1845 Thesis Approved: Dr. William S. Bryans Thesis Adviser Dr. Ron McCoy Dr. L. G. Moses Dr. Lowell Caneday ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My Mom and Dad, Grandma and Pa, and Sister and Brother-in-Law for backing me as I decided to continue my education in a topic I love. Of course my instructors and professors at Southeastern Oklahoma State University who urged me to attend Oklahoma State University for my master’s degree. My advisor and committee, who have helped further my education and probably read some awful drafts of my thesis. The Edmon Low Library Staff which includes Government Documents, Interlibrary Loan, Circulation Desk, and Room 105. The staff at the Oklahoma Historical Society’s Fort Washita historic site with whom I have enjoyed volunteering with over the years and who helped me go through the site’s files. The National Park Service was helpful in trying to find out specific details. Also the librarians of various military colleges and the National Archives which I have contacted who spent time looking for documents and sources that might have been of use to my thesis. Thank you all. -

The Story of the Buffalo Soldiers: the First African Americans to Serve in the Regular Army

we can, WE wiLl! The Story of the Buffalo Soldiers: The First African Americans to Serve in the Regular Army Table of Contents History of the Buffalo Soldiers ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Buffalo Soldier Timeline ................................................................................................................................................... 23 Texas Monthly ......................................................................................................................................................................... 26 Keep Texas Wild .................................................................................................................................................................... 27 Making Connections .......................................................................................................................................................... 31 The Unknown Army ............................................................................................................................................................ 32 Living History Presentations and School Programs ...................................................................................... 40 Color Guard Presentations ............................................................................................................................................. 41 Blazing New Trails ..............................................................................................................................................................