The Story of the Buffalo Soldiers: the First African Americans to Serve in the Regular Army

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Fulton Reynolds

John Fulton Reynolds By COL. JOHN FULTON REYNOLDS SCOTT ( U. S. Army, retired ) Grand-nephew of General Reynolds I CAME here to give a talk on John Fulton Reynolds, and as I have sat here this evening I really feel superfluous. The stu- dents of this school have certainly outdone themselves in their essays on that subject, and I feel that what I may add is more or less duplication. For the sake of the record I will do my best to make a brief talk, and to try to fill in some of the gaps in Reynolds' life which have been left out because some of them have not yet been published. As you have heard, John Reynolds was the second son of the nine children of John Reynolds and Lydia Moore. Lydia Moore's ancestry was entirely Irish. Her father came from Rathmelton, Ireland, served as a captain at Brandywine with the 3rd Penn- sylvania. Infantry of the Continental Line, where he was wounded; also served at Germantown and at Valley Forge, and was then retired. Her mother was Irish on both sides of her family, and the Reynolds family itself was Irish, but, of course, the Huguenot strain came in through John Reynolds' own mother, who was a LeFever and a great-granddaughter of Madam Ferree of Paradise. Our subject was born on September 21, 1820, at 42 West King Street, Lancaster, and subsequently went to the celebrated school at Lititz, conducted by the grandfather of the presiding officer of this meeting, Dr. Herbert H. Beck. I have a letter written by John F. -

Plan Your Next Trip

CHARLES AND MARY ANN GOODNIGHT RANCH STATE HISTORIC SITE, GOODNIGHT PRESERVE THE FUTURE By visiting these historic sites, you are helping the Texas Historical Commission preserve the past. Please be mindful of fragile historic artifacts and respectful of historic structures. We want to ensure their preservation for the enjoyment of future generations. JOIN US Support the preservation of these special places. Consider making a donation to support ongoing preservation and education efforts at our sites at thcfriends.org. Many of our sites offer indoor and outdoor facility rentals for weddings, meetings, and special events. Contact the site for more information. SEE THE SITES From western forts and adobe structures to Victorian mansions and pivotal battlegrounds, the Texas Historical Commission’s state historic sites illustrate the breadth of Texas history. Plan Your Next Trip texashistoricsites.com 1 Acton HISTORIC15 Kreische BrSITESewery DIVISION22 National Museum of the Pacific War 2 Barrington Plantation Texas16 Landmark Historical Inn Commission23 Old Socorro Mission 3 Caddo Mounds P.O.17 BoxLevi 12276,Jordan Plantatio Austin,n TX 7871124 Palmito Ranch Battleground 4 Casa Navarro 18 Lipantitla512-463-7948n 25 Port Isabel Lighthouse 5 Confederate Reunion Grounds [email protected] Magon Home 26 Sabine Pass Battleground 6 Eisenhower Birthplace 20 Mission Dolores 27 Sam Bell Maxey House 7 Fannin Battleground 21 Monument HIll 28 Sam Rayburn House 8 Fanthorp Inn 29 San Felipe de Austin 9 Fort Grin 30 San Jacinto Battleground and -

89.1963.1 Iron Brigade Commander Wayne County Marker Text Review Report 2/16/2015

89.1963.1 Iron Brigade Commander Wayne County Marker Text Review Report 2/16/2015 Marker Text One-quarter mile south of this marker is the home of General Solomon A. Meredith, Iron Brigade Commander at Gettysburg. Born in North Carolina, Meredith was an Indiana political leader and post-war Surveyor-General of Montana Territory. Report The Bureau placed this marker under review because its file lacked both primary and secondary documentation. IHB researchers were able to locate primary sources to support the claims made by the marker. The following report expands upon the marker points and addresses various omissions, including specifics about Meredith’s political service before and after the war. Solomon Meredith was born in Guilford County, North Carolina on May 29, 1810.1 By 1830, his family had relocated to Center Township, Wayne County, Indiana.2 Meredith soon turned to farming and raising stock; in the 1850s, he purchased property near Cambridge City, which became known as Oakland Farm, where he grew crops and raised award-winning cattle.3 Meredith also embarked on a varied political career. He served as a member of the Wayne County Whig convention in 1839.4 During this period, Meredith became concerned with state internal improvements: in the early 1840s, he supported the development of the Whitewater Canal, which terminated in Cambridge City.5 Voters next chose Meredith as their representative to the Indiana House of Representatives in 1846 and they reelected him to that position in 1847 and 1848.6 From 1849-1853, Meredith served -

Oklahoma, Kansas, and Texas Draft Joint EIS/BLM RMP and BIA Integrated RMP

Poster 1 Richardson County Lovewell Washington State Surface Ownership and BLM- Wildlife Lovewell Fishing Lake And Falls City Reservoir Wildlife Area St. Francis Keith Area Brown State Wildlife Sebelius Lake Norton Phillips Brown State Fishing Lake And Area Cheyenne (Norton Lake) Wildlife Area Washington Marshall County Smith County Nemaha Fishing Lake Wildlife Area County Lovewell State £77 County Administered Federal Minerals Rawlins State Park ¤ Wildlife Sabetha ¤£36 Decatur Norton Fishing Lake Area County Republic County Norton County Marysville ¤£75 36 36 Brown County ¤£ £36 County ¤£ Washington Phillipsburg ¤ Jewell County Nemaha County Doniphan County St. 283 ¤£ Atchison State County Joseph Kirwin National Glen Elder BLM-administered federal mineral estate Reservoir Jamestown Tuttle Fishing Lake Wildlife Refuge Sherman (Waconda Lake) Wildlife Area Creek Atchison State Fishing Webster Lake 83 State Glen Elder Lake And Wildlife Area County ¤£ Sheridan Nicodemus Tuttle Pottawatomie State Thomas County Park Webster Lake Wildlife Area Concordia State National Creek State Fishing Lake No. Atchison Bureau of Indian Affairs-managed surface Fishing Lake Historic Site Rooks County Parks 1 And Wildlife ¤£159 Fort Colby Cloud County Atchison Leavenworth Goodland 24 Beloit Clay County Holton 70 ¤£ Sheridan Osborne Riley County §¨¦ 24 County Glen Elder ¤£ Jackson 73 County Graham County Rooks State County ¤£ lands State Park Mitchell Clay Center Pottawatomie County Sherman State Fishing Lake And ¤£59 Leavenworth Wildlife Area County County Fishing -

The African American Soldier at Fort Huachuca, Arizona, 1892-1946

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Faculty Publications Anthropology, Department of 2-2001 The African American Soldier At Fort Huachuca, Arizona, 1892-1946 Steven D. Smith University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/anth_facpub Part of the Anthropology Commons Publication Info Published in 2001. © 2001, University of South Carolina--South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology This Book is brought to you by the Anthropology, Department of at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE AFRICAN AMERICAN SOLDIER AT FORT HUACHUCA, ARIZONA, 1892-1946 The U.S Army Fort Huachuca, Arizona, And the Center of Expertise for Preservation of Structures and Buildings U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Seattle District Seattle, Washington THE AFRICAN AMERICAN SOLDIER AT FORT HUACHUCA, ARIZONA, 1892-1946 By Steven D. Smith South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology University of South Carolina Prepared For: U.S. Army Fort Huachuca, Arizona And the The Center of Expertise for Preservation of Historic Structures & Buildings, U.S. Army Corps of Engineer, Seattle District Under Contract No. DACW67-00-P-4028 February 2001 ABSTRACT This study examines the history of African American soldiers at Fort Huachuca, Arizona from 1892 until 1946. It was during this period that U.S. Army policy required that African Americans serve in separate military units from white soldiers. All four of the United States Congressionally mandated all-black units were stationed at Fort Huachuca during this period, beginning with the 24th Infantry and following in chronological order; the 9th Cavalry, the 10th Cavalry, and the 25th Infantry. -

FRIENDS of THC BOARD of DIRECTORS Name Address City State Zip Work Home Mobile Email Email Code Killis P

FRIENDS OF THC BOARD OF DIRECTORS Name Address City State Zip Work Home Mobile Email Email Code Killis P. Almond 342 Wilkens San TX 78210 210-532-3212 512-532-3212 [email protected] Avenue Antonio Peggy Cope Bailey 3023 Chevy Houston TX 77019 713-523-4552 713-301-7846 [email protected] Chase Drive Jane Barnhill 4800 Old Brenham TX 77833 979-836-6717 [email protected] Chappell Hill Road Jan Felts Bullock 3001 Gilbert Austin TX 78703 512-499-0624 512-970-5719 [email protected] Street Diane D. Bumpas 5306 Surrey Dallas TX 75209 214-350-1582 [email protected] Circle Lareatha H. Clay 1411 Pecos Dallas TX 75204 214-914-8137 [email protected] [email protected] Street Dianne Duncan Tucker 2199 Troon Houston TX 77019 713-524-5298 713-824-6708 [email protected] Road Sarita Hixon 3412 Houston TX 77027 713-622-9024 713-805-1697 [email protected] Meadowlake Lane Lewis A. Jones 601 Clark Cove Buda TX 78610 512-312-2872 512-657-3120 [email protected] Harriet Latimer 9 Bash Place Houston TX 77027 713-526-5397 [email protected] John Mayfield 3824 Avenue F Austin TX 78751 512-322-9207 512-482-0509 512-750-6448 [email protected] Lynn McBee 3912 Miramar Dallas TX 75205 214-707-7065 [email protected] [email protected] Avenue Bonnie McKee P.O. Box 120 Saint Jo TX 76265 940-995-2349 214-803-6635 [email protected] John L. Nau P.O. Box 2743 Houston TX 77252 713-855-6330 [email protected] [email protected] Virginia S. -

Battle of Gettysburg Day 1 Reading Comprehension Name: ______

Battle of Gettysburg Day 1 Reading Comprehension Name: _________________________ Read the passage and answer the questions. The Ridges of Gettysburg Anticipating a Confederate assault, Union Brigadier General John Buford and his soldiers would produce the first line of defense. Buford positioned his defenses along three ridges west of the town. Buford's goal was simply to delay the Confederate advance with his small cavalry unit until greater Union forces could assemble their defenses on the three storied ridges south of town known as Cemetery Ridge, Cemetery Hill, and Culp's Hill's. These ridges were crucial to control of Gettysburg. Whichever army could successfully occupy these heights would have superior position and would be difficult to dislodge. The Death of Major General Reynolds The first of the Confederate forces to engage at Gettysburg, under the Command of Major General Henry Heth, succeeded in advancing forward despite Buford's defenses. Soon, battles erupted in several locations, and Union forces would suffer severe casualties. Union Major General John Reynolds would be killed in battle while positioning his troops. Major General Abner Doubleday, the man eventually credited with inventing the formal game of baseball, would assume command. Fighting would intensify on a road known as the Chambersburg Pike, as Confederate forces continued to advance. Jubal Early's Successful Assault Meanwhile, Union defenses positioned north and northwest of town would soon be outflanked by Confederates under the command of Jubal Early and Robert Rodes. Despite suffering severe casualties, Early's soldiers would break through the line under the command of Union General Francis Barlow, attacking them from multiple sides and completely overwhelming them. -

Ti--1E Wheeler Times

TI--1E WHEELER TIMES (USPS 681-960) VOLUME 71, NUMBER 36 THURSDAY, AUGUST 18, 2005 SINGLE COPY 50 c "Wheeler, town of friendship and pride. " CWECHAT Certificate Given WITH City Of Wheeler EDITOR The certificate reads: By Louis C. Stas "The State of Texas Governor School has started and once To all to whom these presents • again, we wonder 'where has the shall come, Greeting: Know ye, summer gone?' that --cwe— this certificate is presented to Football is also under way with a the: scrimmage with Paducah on Fri- City of Wheeler day here at 5:00 p.m. Congratulations to you all as the -CIA/ 8- great City of Wheeler celebrates And, the annual Meet the Mus- its 100th anniversary. Eagerly an- • tangs will be next Tuesday, Au- ticipated, this grand celebration gust 23. Make plans to be at highlights the best of Texas. Em- Nicholson Field to meet Wheeler's bracing your heritage and history, 2005-2006 athletes, band students you can retied with pride on both and cheerleaders. your outstanding record of accom- - Owe- plishment and on your ongoing Wheeler only received 0.52" of commitment to forging new paths rain'over the weekend with reports of excellence into the future. of 2". and 5" in the area. But, we PRESENTATION: At a meeting of the Wheeler City Council, the Wheeler Centennial Committee presented a certificate from Governor Rick appreciate what moisture we got. Today all in the Lone Star State Perry, congratulating Wheeler on its 100th birthday. Louis Stas, representing the centennial committee, presented the document to Mayor —cwe— join in celebration. -

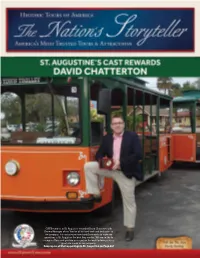

St. Augustine Rewarded David Chatterton with General Manager of the Year for All His Hard Work and Dedication to the Company

CASTmembers in St. Augustine rewarded David Chatterton with General Manager of the Year for all his hard work and dedication to the company. It is not a secret how hard Dave works to make the operations in St. Augustine the best they can be. We would like to recognize Dave and give him a nice pat on the back for being such a great role model for our company. Keep up on all the happenings in St. Augustine on Page 26! FROM THE DESK OF THE CHIEF CONDUCTOR IN THE AGE OF DISRUPTION … WHAT NEXT? by Chris Belland, CEO It seems as though we are living in one strategy of using words to describe of the most disruptive moments in political what we do to make sure no one ever and economic history. Trump has made an forgot what business we are in. We are art form of running an outrageous campaign not employees but “CASTmembers”; and shows no signs of slacking off as the new we are not just leaders of people or President. things, we are “Leadagers”. We don’t I wondered, with great incredulity, at have jobs, but we all play a “role” in Trump’s tactics during the campaign, doing delivering a vast array of products and such things as ridiculing John McCain’s war record, going to media “Transportainment” opportunities for war with parents of fallen soldiers and shirking off some egregious our guests. comportment with the opposite sex. Now, as President, with the The result? Historic Tours of Christopher Belland stroke of a pen, he has repudiated Obamacare, attempted to stop America has grown from a single Chief Executive Officer all immigration from a select number of countries and is gutting trolley company, originally with 13 banking regulations put into place after the recent “great recession”. -

Black Recipients of the Medal of Honor from the Frontier Indian Wars

National Historic Site National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Fort Davis BLACK RECIPIENTS OF THE MEDAL OF HONOR FROM THE FRONTIER INDIAN WARS The Medal of Honor is the highest award that can be July 9, 1870, just six weeks after the engagements with given to a member of the Armed Services of the United the Apaches, Emanuel Stance was awarded the Medal of States. It is presented by the president, in the name of Honor. Congress, to an individual who while serving his country “distinguished himself conspicuously by gallantry and George Jordan served at Fort Davis with the Ninth intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the Cavalry from April 1868 to May 1871. During this time, call of duty.” The Medal of Honor was authorized in he was often in the field scouting for the elusive 1862 and first presented in 1863 to soldiers and sailors Apaches and Comanches who were raiding in western who demonstrated extraordinary examples of courage in Texas and southeastern New Mexico. On the Civil War. one occasion he was part of a two-hundred-man force Devotion to Duty detailed to track a party of Mescalero Apaches in the Guadalupe Mountains. The experience Jordan gained Between 1865 and 1899, the Medal of Honor was proved invaluable. On May 14, 1880 Sergeant Jordan, in awarded to 417 men who served in the frontier Indian command of a small detachment of soldiers, defended Campaigns. Eighteen of the medals were earned by men Tularosa, New Mexico Territory, against the Apache of African-American descent. -

Texas Forts Trail Region

CatchCatch thethe PioPionneereer SpiritSpirit estern military posts composed of wood and While millions of buffalo still roamed the Great stone structures were grouped around an Plains in the 1870s, underpinning the Plains Indian open parade ground. Buildings typically way of life, the systematic slaughter of the animals had included separate officer and enlisted troop decimated the vast southern herd in Texas by the time housing, a hospital and morgue, a bakery and the first railroads arrived in the 1880s. Buffalo bones sutler’s store (provisions), horse stables and still littered the area and railroads proved a boon to storehouses. Troops used these remote outposts to the bone trade with eastern markets for use in the launch, and recuperate from, periodic patrols across production of buttons, meal and calcium phosphate. the immense Southern Plains. The Army had other motivations. It encouraged Settlements often sprang up near forts for safety the kill-off as a way to drive Plains Indians onto and Army contract work. Many were dangerous places reservations. Comanches, Kiowas and Kiowa Apaches with desperate characters. responded with raids on settlements, wagon trains and troop movements, sometimes kidnapping individuals and stealing horses and supplies. Soldiers stationed at frontier forts launched a relentless military campaign, the Red River War of 1874–75, which eventually forced Experience the region’s dramatic the state’s last free Native Americans onto reservations in present-day Oklahoma. past through historic sites, museums and courthouses — as well as historic downtowns offering unique shopping, dining and entertainment. ★★ ★★ ★★ ★★ ★★ ★★ ★★ 2 The westward push of settlements also relocated During World War II, the vast land proved perfect cattle drives bound for railheads in Kansas and beyond. -

Book Reviews

East Texas Historical Journal Volume 46 Issue 2 Article 13 10-2008 Book Reviews Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj Part of the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Recommended Citation (2008) "Book Reviews," East Texas Historical Journal: Vol. 46 : Iss. 2 , Article 13. Available at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj/vol46/iss2/13 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the History at SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in East Texas Historical Journal by an authorized editor of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EAST TEXAS HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION 7l BOOK REVIEWS Lone Star Pasts: Memo!)' and History in Texas, Gregg Cantrell and Elizabeth Hayes Turner, editors (Tcxas A&M University Prcss, 4354 TAMU. Collcge Station, TX 77843-4354) 2007. Contents, Illus. Contributors. Index. P. 296. $19.95. Paperback. $45. Hardcover. During the 1980s, French sociologist Maurice Halbwachs and French social scientist Pierre Nora devcloped the concept of "collectivc memory," an idea that swept the academic world and seemed particularly apt for Texas. Gregg Cantrell and Elizabeth Hayes Turner brought together eleven eminent and entertaining authors to produce collective memories that often challenge factual histories. The articles point out that historians are often ignored by the Texas pub lic who shaped their own version of their pasts. Articles focus on battles fought by the Daughters of the Republic ofTexas over who would restore the Alamo, the United Daughters of the Confederacy in their attempts to commemorate Confederate heroes, and the attempts by the Ku Klux Klan to Ameril:anize their message in the 1920s.