Garrison Life of the Mounted Soldier on the Great Plains

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Modern Application of Mechanized-Cavalry Groups for Cavalry Echelons Above Brigade by MAJ Joseph J

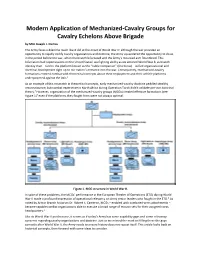

Modern Application of Mechanized-Cavalry Groups for Cavalry Echelons Above Brigade by MAJ Joseph J. Dumas The Army faces a dilemma much like it did at the onset of World War II: although the war provided an opportunity to rapidly codify cavalry organizations and doctrine, the Army squandered the opportunity to do so in the period before the war, when the branch bifurcated and the Army’s mounted arm floundered. This bifurcation had repercussions on the United States’ warfighting ability as we entered World War II, as branch identity then – tied to the platform known as the “noble companion” (the horse) – stifled organizational and doctrinal development right up to our nation’s entrance into the war. Consequently, mechanized-cavalry formations entered combat with theoretical concepts about their employment and their vehicle platforms underpowered against the Axis.1 As an example of this mismatch in theoretical concepts, early mechanized-cavalry doctrine peddled stealthy reconnaissance, but combat experience in North Africa during Operation Torch didn’t validate pre-war doctrinal theory.2 However, organization of the mechanized-cavalry groups (MCGs) created effective formations (see Figure 1)3 even if the platforms they fought from were not always optimal. Figure 1. MCG structure in World War II. In spite of these problems, the MCGs’ performance in the European Theater of Operations (ETO) during World War II made a profound impression of operational relevancy on Army senior leaders who fought in the ETO.4 As noted by Armor Branch historian Dr. Robert S. Cameron, MCGs – enabled with combined-arms attachments – became capable combat organizations able to execute a broad range of mission sets for their assigned corps headquarters.5 Like its World War II predecessor, it seems as if today’s Army has some capability gaps and some relevancy concerns regarding cavalry organizations and doctrine. -

United Nations Manual for the Generation and Deployment of Military and Formed Police Units to Peace Operations

United Nations Manual for the Generation and Deployment of Military and Formed Police Units to Peace Operations May 2021 DEPARTMENT OF PEACE OPERATIONS DEPARTMENT OF OPERATIONAL SUPPORT 0 Produced by: Office of Military Affairs and Office of the Police Adviser Department of Peace Operations UN Secretariat New York, NY 10017 Tel. 917-367-2487 Approved by: Jean-Pierre Lacroix, Under-Secretary-General for Peace Operations Department of Peace Operations (DPO). Atul Khare Under-Secretary-General for Operational Support Department of Operational Support (DOS) This is the first version of this Manual, May 2021 Contact: DPO/OMA/FGS and DPO/PD/SRS Review date: May 2024 Reference number: 2021.05 Printed at the UN, New York © UN 2021. This publication enjoys copyright under Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. Nevertheless, governmental authorities or Member States may freely photocopy any part of this publication for exclusive use within their training institutes. However, no portion of this publication may be reproduced for sale or mass publication without the express consent, in writing, of the Office of Military Affairs and Office of the Police Adviser, UN Department of Peace Operations. 1 Contents Preface ............................................................................................................................................................4 Purpose and Scope .........................................................................................................................................4 Chapter 1. Introduction -

GAO-05-419T Military Personnel: Preliminary Observations On

United States Government Accountability Office Testimony GAO Before the Subcommittee on Military Personnel, Committee on Armed Services, House of Representatives For Release on Delivery Expected at 2:00 p.m. EST MILITARY PERSONNEL Wednesday, March 16, 2005 Preliminary Observations on Recruiting and Retention Issues within the U.S. Armed Forces Statement of Derek B. Stewart, Director, Defense Capabilities and Management a GAO-05-419T March 16, 2005 MILITARY PERSONNEL Accountability Integrity Reliability Highlights Preliminary Observations on Recruiting Highlights of GAO-05-419T, a testimony to and Retention Issues within the U.S. the Chairman, Subcommittee on Military Personnel, Committee on Armed Services, Armed Forces House of Representatives Why GAO Did This Study What GAO Found To meet its human capital needs, DOD’s 10 military components generally met their overall recruitment and the Department of Defense (DOD) retention goals for each of the past 5 fiscal years (FY), but some of the must convince several hundred components experienced difficulties in meeting their overall goals in early thousand people to join the military FY 2005. However, it should be noted that several components introduced a each year while, at the same time, “stop loss” policy shortly after September 11, 2001. The “stop loss” policy retain thousands of personnel to sustain its active duty, reserve, and requires some servicemembers to remain in the military beyond their National Guard forces. Since contract separation date, which may reduce the number of personnel the September 11, 2001, DOD has components must recruit. During FY 2000-2004, each of the active launched three major military components met or exceeded their overall recruiting goals. -

The Army Post on the Northern Plains, 1865-1885

The Army Post on the Northern Plains, 1865-1885 (Article begins on page 2 below.) This article is copyrighted by History Nebraska (formerly the Nebraska State Historical Society). You may download it for your personal use. For permission to re-use materials, or for photo ordering information, see: https://history.nebraska.gov/publications/re-use-nshs-materials Learn more about Nebraska History (and search articles) here: https://history.nebraska.gov/publications/nebraska-history-magazine History Nebraska members receive four issues of Nebraska History annually: https://history.nebraska.gov/get-involved/membership Full Citation: Ray H. Mattison, “The Army Post on the Northern Plains, 1865-1885,” Nebraska History 35 (1954): 17-43 Article Summary: Frontier garrisons played a significant role in the development of the West even though their military effectiveness has been questioned. The author describes daily life on the posts, which provided protection to the emigrants heading west and kept the roads open. Note: A list of military posts in the Northern Plains follows the article. Cataloging Information: Photographs / Images: map of Army posts in the Northern Plains states, 1860-1895; Fort Laramie c. 1884; Fort Totten, Dakota Territory, c. 1867 THE ARMY POST ON THE NORTHERN PLAINS, 1865-1885 BY RAY H. MATTISON HE opening of the Oregon Trail, together with the dis covery of gold in California and the cession of the TMexican Territory to the United States in 1848, re sulted in a great migration to the trans-Mississippi West. As a result, a new line of military posts was needed to guard the emigrant and supply trains as well as to furnish protection for the Overland Mail and the new settlements.1 The wiping out of Lt. -

Volume 2A: Chapter 2: Military Personnel Appropriations

DoD Financial Management Regulation Volume 2A, Chapter 2 +June 2004 CHAPTER 2 MILITARY PERSONNEL APPROPRIATIONS Table of Contents 0201 GENERAL ...................................................................................................................................................1 020101 Purpose ..................................................................................................................................................1 0202 ACTIVE MILITARY PERSONNEL APPROPRIATIONS ....................................................................2 020201 General...................................................................................................................................................2 020202 Uniform Budget and Fiscal Accounting Classification .........................................................................2 020203 Budget Presentation Structure Requirements ......................................................................................16 020204 Program and Budget Review Submission............................................................................................22 020205 Congressional Justification/Presentation .............................................................................................24 0203 RESERVE MILITARY PERSONNEL APPROPRIATIONS...............................................................25 020301 General.................................................................................................................................................25 -

Law of Armed Conflict

Lesson 1 THE LAW OF ARMED CONFLICT Basic knowledge International Committee of the Red Cross Unit for Relations with Armed and Security Forces 19 Avenue de la Paix 1202 Geneva, Switzerland T +41 22 734 60 01 F +41 22 733 20 57 E-mail: [email protected] www.icrc.org Original: English – June 2002 INTRODUCTION TO THE LAW OF ARMED CONFLICT BASIC KNOWLEDGE LESSON 1 [ Slide 2] AIM [ Slide 3] The aim of this lesson is to introduce the topic to the class, covering the following main points: 1. Background: setting the scene. 2. The need for compliance. 3. How the law evolved and its main components. 4. When does the law apply? 5. The basic principles of the law. INTRODUCTION TO THE LAW OF ARMED CONFLICT 1. BACKGROUND: SETTING THE SCENE Today we begin a series of lectures on the law of armed conflict, which is also known as the law of war, international humanitarian law, or simply IHL. To begin, I’d like to take a guess at what you’re thinking right now. Some of you are probably thinking that this is an ideal opportunity to catch up on some well-earned rest. “Thank goodness I’m not on the assault course or on manoeuvres. This is absolutely marvellous. I can switch off and let this instructor ramble on for 45 minutes. I know all about the Geneva Conventions anyway – the law is part of my culture and our military traditions. I really don't need to listen to all this legal ‘mumbo jumbo’.” The more sceptical and cynical among you might well be thinking along the lines of a very famous orator of ancient Rome – Cicero. -

The African American Soldier at Fort Huachuca, Arizona, 1892-1946

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Faculty Publications Anthropology, Department of 2-2001 The African American Soldier At Fort Huachuca, Arizona, 1892-1946 Steven D. Smith University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/anth_facpub Part of the Anthropology Commons Publication Info Published in 2001. © 2001, University of South Carolina--South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology This Book is brought to you by the Anthropology, Department of at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE AFRICAN AMERICAN SOLDIER AT FORT HUACHUCA, ARIZONA, 1892-1946 The U.S Army Fort Huachuca, Arizona, And the Center of Expertise for Preservation of Structures and Buildings U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Seattle District Seattle, Washington THE AFRICAN AMERICAN SOLDIER AT FORT HUACHUCA, ARIZONA, 1892-1946 By Steven D. Smith South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology University of South Carolina Prepared For: U.S. Army Fort Huachuca, Arizona And the The Center of Expertise for Preservation of Historic Structures & Buildings, U.S. Army Corps of Engineer, Seattle District Under Contract No. DACW67-00-P-4028 February 2001 ABSTRACT This study examines the history of African American soldiers at Fort Huachuca, Arizona from 1892 until 1946. It was during this period that U.S. Army policy required that African Americans serve in separate military units from white soldiers. All four of the United States Congressionally mandated all-black units were stationed at Fort Huachuca during this period, beginning with the 24th Infantry and following in chronological order; the 9th Cavalry, the 10th Cavalry, and the 25th Infantry. -

Navigating Current and Emerging Army Recruiting Challenges: What Can Research Tell Us?

C O R P O R A T I O N BETH J. ASCH Navigating Current and Emerging Army Recruiting Challenges What Can Research Tell Us? For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR3107 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-1-9774-0403-9 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2019 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover: SDI Productions/Getty Images Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Executive Summary Recruiting is the foundation of the U.S. Army’s ability to sustain its overall force levels, but recruiting has become very challenging. -

Congressional Record- House. May 23

5868 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD- HOUSE. MAY 23, Homer B. Grant, of Massachusetts, late first lieutenant, Twenty Irwin G. Lukens, to be postmaster at North Wales, in the county sixth Infantry, United States Volunteers (now second lieutenant, of Montgomery and State of Pe..~ylvania. Artillery Corps, United States Army), to fill an original vacancy. Benjamin Jacobs, to be postmaster at Pencoyd, in the county John W. C. Abbott, at large, late first lieutenant, Thirtieth In of Montgomery and State of Pennsylvania. fantry, United States Volunteers (now second lieutenant, Artillery JohnS. Buchanan, to be postmaster at Ambler, in the county Corps, United States Army), to fill an original vacancy. of Montgomery and State of Pennsylvania. John McBride, jr., at large, late first lieutenant, Thirtieth In Henry C. Connaway, to be postmaster at Berlin, in the county fantry, United States Volunteers (now second lieutenant, Artillery of Worcester and State of Mal'yland. Corps, United States Army), to fill an original vacancy. Harrison S. Kerrick, of Illinois, late captain, Thirtieth Infan try, United States Volunteers (now second lieutenant, Artillery HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES. Corps, United States Army), to fill an original vacancy. Frank J. Miller, at large, late first lieutenant, Forty-first Infan FRIDAY, May 23, 1902. try, United States Volunteers (now second lieutenant, Artillery The House met at 12 o'clock m. Prayer by the Chaplain, Rev. Corps, United States Army), to fill an original vacancy. HENRY N. COUDEN, D. D. Charles L. Lanham, at large, late first lieutenant, Forty-seventh The Journal of the proceedings of yestel'day was read and ap Infantry, United States Volunteers (now second lieutenant, Artil proved. -

70Th Annual 1St Cavalry Division Association Reunion

1st Cavalry Division Association 302 N. Main St. Non-Profit Organization Copperas Cove, Texas 76522-1703 US. Postage PAID West, TX Change Service Requested 76691 Permit No. 39 PublishedSABER By and For the Veterans of the Famous 1st Cavalry Division VOLUME 66 NUMBER 1 Website: http://www.1cda.org JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2017 The President’s Corner Horse Detachment by CPT Jeremy A. Woodard Scott B. Smith This will be my last Horse Detachment to Represent First Team in Inauguration Parade By Sgt. 833 State Highway11 President’s Corner. It is with Carolyn Hart, 1st Cav. Div. Public Affairs, Fort Hood, Texas. Laramie, WY 82070-9721 deep humility and considerable A long standing tradition is being (307) 742-3504 upheld as the 1st Cavalry Division <[email protected]> sorrow that I must announce my resignation as the President Horse Cavalry Detachment gears up to participate in the Inauguration of the 1st Cavalry Division Association effective Saturday, 25 February 2017. Day parade Jan. 20 in Washington, I must say, first of all, that I have enjoyed my association with all of you over D.C. This will be the detachment’s the years…at Reunions, at Chapter meetings, at coffees, at casual b.s. sessions, fifth time participating in the event. and at various activities. My assignments to the 1st Cavalry Division itself and “It’s a tremendous honor to be able my friendships with you have been some of the highpoints of my life. to do this,” Capt. Jeremy Woodard, To my regret, my medical/physical condition precludes me from travelling. -

“Remarkable Stratagems and Conspiracies” : How Unscrupulous

“REMARKABLE STRATAGEMS AND CONSPIRACIES”: HOW UNSCRUPULOUS LAWYERS AND CREDULOUS JUDGES CREATED AN EXCEPTION TO THE HEARSAY RULE Marianne Wesson* This essay has a somewhat different goal than the other contributions to this Symposium: rather than considering present-day ethical predicaments, it aims to inspire reflection on an episode in which improper and unprofessional conduct by attorneys contributed to the creation of the law of evidence. In particular, it considers the events that led to the formulation and enactment of a rule that persistently affects the conduct of trials even by the most responsible and ethical lawyers: the hearsay exception codified as Federal Rule of Evidence 803(3).1 The bare bones of the narrative are well-known to nearly every lawyer, as it has formed a staple of the study of the law of evidence since the date of the U.S. Supreme Court’s first decision on the matter in 1892, in Mutual Life Insurance Company of New York v. Hillmon.2 Even the lay public was transfixed by the story in its time; the tale of John Hillmon was the subject * Marianne Wesson, Professor of Law, Wolf-Nichol Fellow, and President’s Teaching Scholar, University of Colorado School of Law. The author is grateful for the excellent research and editorial assistance of Andrea Viedt in the preparation of this essay. 1. The rule provides an exception to the general rule excluding hearsay for a statement of the declarant’s then existing state of mind, emotion, sensation, or physical condition (such as intent, plan, motive, design, mental feeling, pain, and bodily health), but not including a statement of memory or belief to prove the fact remembered or believed unless it relates to the execution, revocation, identification, or terms of declarant’s will. -

Reconstruction Report

RECONSTRUCTION IN AMERICA RECONSTRUCTION 122 Commerce Street Montgomery, Alabama 36104 334.269.1803 eji.org RECONSTRUCTION IN AMERICA Racial Violence after the Civil War, 1865-1876 © 2020 by Equal Justice Initiative. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, modified, or distributed in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means without express prior written permission of Equal Justice Initiative. RECONSTRUCTION IN AMERICA Racial Violence after the Civil War, 1865-1876 The Memorial at the EJI Legacy Pavilion in Montgomery, Alabama. (Mickey Welsh/Montgomery Advertiser) 5 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 6 THE DANGER OF FREEDOM 56 Political Violence 58 Economic Intimidation 63 JOURNEY TO FREEDOM 8 Enforcing the Racial Social Order 68 Emancipation and Citizenship Organized Terror and Community Massacres 73 Inequality After Enslavement 11 Accusations of Crime 76 Emancipation by Proclamation—Then by Law 14 Arbitrary and Random Violence 78 FREEDOM TO FEAR 22 RECONSTRUCTION’S END 82 A Terrifying and Deadly Backlash Reconstruction vs. Southern Redemption 84 Black Political Mobilization and White Backlash 28 Judicial and Political Abandonment 86 Fighting for Education 32 Redemption Wins 89 Resisting Economic Exploitation 34 A Vanishing Hope 93 DOCUMENTING RECONSTRUCTION 42 A TRUTH THAT NEEDS TELLING 96 VIOLENCE Known and Unknown Horrors Notes 106 Acknowledgments 119 34 Documented Mass Lynchings During the Reconstruction Era 48 Racial Terror and Reconstruction: A State Snapshot 52 7 INTRODUCTION Thousands more were assaulted, raped, or in- jured in racial terror attacks between 1865 and 1876. The rate of documented racial terror lynchings during Reconstruction is nearly three In 1865, after two and a half centuries of brutal white mobs and individuals who were shielded It was during Reconstruction that a times greater than during the era we reported enslavement, Black Americans had great hope from arrest and prosecution.